Written by Mark Connelly

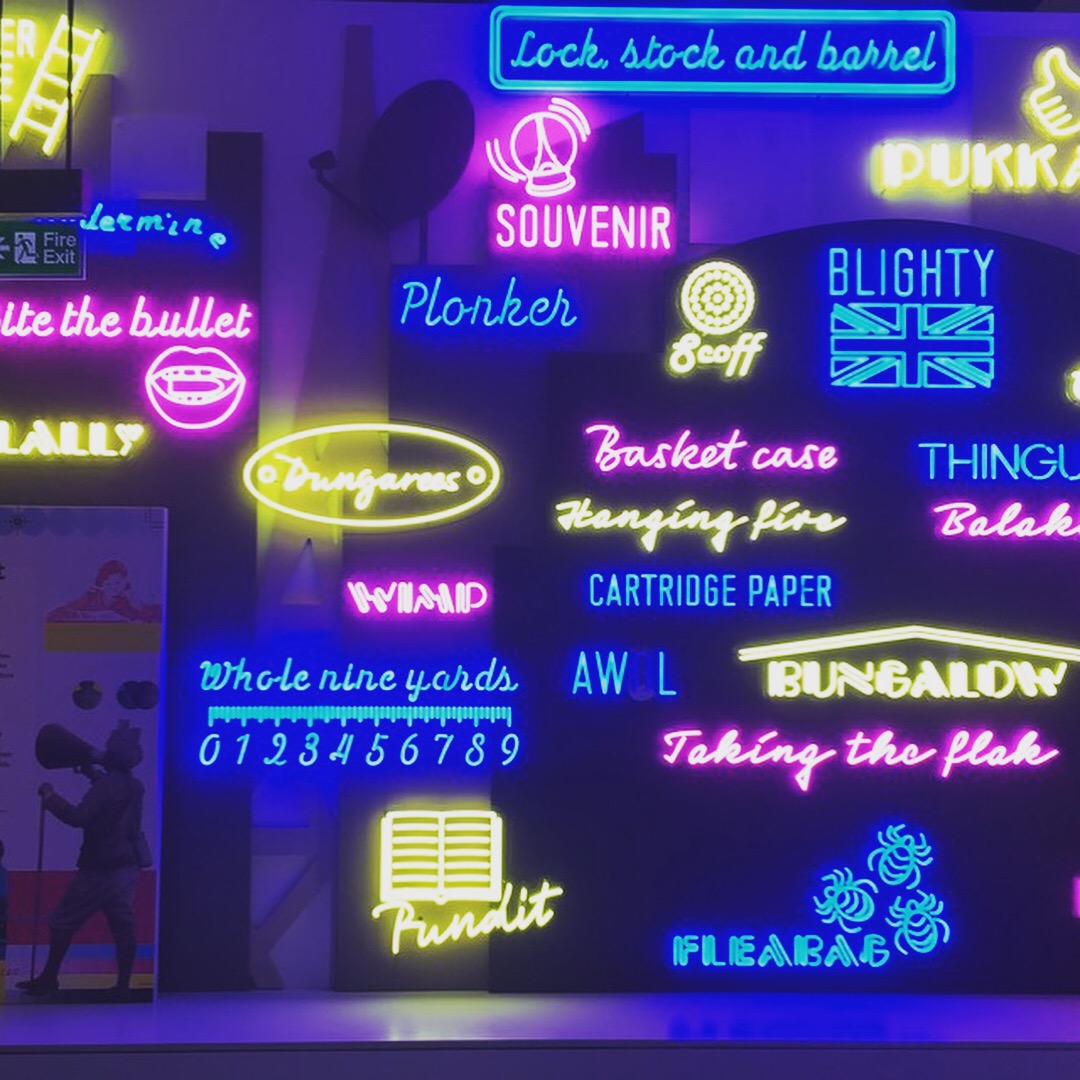

Every now and then a book comes along that meets truly the hyperbole of blurbs and testimonials found in reviews and adorning dustjacket covers. For me, one of those texts is Paul Fussell’s The Great War and Modern Memory. First published by Oxford University Press in 1975, it has achieved something rare for an academic text: global fame and global notoriety. His argument that the Great War ushered in irony as the dominant mode of modern discourse was ever-present set people talking, thinking and writing, some furiously, others ecstatically. My first engagement with it was as a teenager and through the lenses of others. The first was provided by an English teacher at school who, on finding out about my interest in the First World War, urged me to read it. With the persistence of a Great War general hammering away at a strongpoint regardless of cost, he kept returning to the recommendation. I noted his enthusiasm and realised there was something special about this work, but I had a pile of other war books to get through including Wyn Griffiths’s Up to Mametz and the diaries of Edwin Campion Vaughan published under the title Some Desperate Glory. My next encounter with it came at Christmas when my parents indulged me with another pile of First World War books as presents. Among them were two other seminal texts (if you’re unlucky, I’ll write about those in another blog!), John Terraine’s The Smoke and the Fire and The White Heat. Reading The Smoke and the Fire was epiphanic (that’s a great word, isn’t it?). I went from being a full-blown Joan Littlewoodite to a full-blown revisionist in one move. And of course, a significant casualty was my open-mindedness about Fussell. This Fussell chap now looked distinctly suspect and out of his depth. As Bertie Wooster might have said, ‘Fussell can eat cake as far as I am concerned’, and that was him struck from my reading list.