Reviewed by Edward Corse

Nordic Media Histories of Propaganda and Persuasion, edited by Fredrik Norén, Emil Stjernholm and C. Claire Thomson, is a welcome addition to the historical literature on the topic of propaganda. The book, published by Palgrave Macmillan, is Open Access and well worth downloading here to explore issues around propaganda and persuasion in a Nordic setting. The book stems from a conference held in the summer of 2020 in hybrid format hosted by Lund University. I attended this fascinating conference virtually and I am excited to see the final result of the work the convenors and contributors have compiled over the past couple of years. Written in English, the 18 authors are largely based in the Nordic countries themselves, with two exceptions: Nicholas J. Cull (University of Southern California, USA), who has written one of the afterwords; and one of the editors, C. Claire Thomson (UCL, UK).

Taking a transnational approach, covering mainly Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland (with occasional references to Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands) the book delves into the very essence of what it means to be Nordic. The case studies stretch from the 1930s, with Ruth Hemstad’s chapter exploring early manifestations of ‘Norden’ (a brand symbolising Nordic unity), to the present day. Searching for commonalities and attempting to understand differences between the Nordic nations, the book seeks to unlock the components of what makes up the so-called ‘Nordic model’ from a variety of angles and case studies throughout the twentieth century. The volume rightly describes these studies as ‘histories’ rather than ‘a history’, showing that there are a variety of perspectives and views on what makes up the subject matter. These are definitely case studies that help illuminate questions and debates, rather than seeking to provide a comprehensive analysis (which would be impossible anyway), and it is well framed in its coverage. The topics include studies of films and television, cultural diplomacy, education, public information, anti-abortion campaigns, national security, the environment and development aid.

Similarities amongst the Nordic nations include, of course, some closeness of language (at least for the three countries than can be said to make up ‘Scandinavia’), the welfare state and democratic traditions, and membership of the Nordic Council (established in 1952). The volume shows that often these similarities have been seen as adding up to something bigger than the constituent elements, or at least that is how it could be presented. Despite those similarities and being geographically close, there are numerous differences in culture, politics and in their histories that have separately shaped each of the Nordic nations. Their different experiences in the Second World War were, of course, particularly stark, but even in later periods, as Cull points out, differences towards membership of NATO, the EU and the Euro currency are also noticeable. The book persuasively argues that propaganda and persuasion have played a key role in the shaping of both these differences and similarities, resulting in a complex identity.

The authors contribute to the perennial debate about the meaning and use of the word ‘propaganda’ – and how it interacts with the ‘seemingly softer term “persuasion”’ as well as other similar terms. These include ‘cultural diplomacy’, ‘education’ and the work of organisations such as the Fulbright Program which can have propagandistic tendencies. These forms of persuasion are referred to in Jukka Kortti’s chapter as ‘slow media’. Often the book describes these different forms of media as being interrelated or ‘entangled’ and it is certainly true that none of these different elements can be viewed in isolation. The debate is elaborated upon in one of the afterwords by Peter Stadius as well as being explored in many of the chapters themselves.

The book overall provides a transnational approach, and so do many of the chapters individually. For example, Norén considers whether it is possible to draw together a Nordic model of public information in the 1970s, demonstrating some commonality of approach through regulation and deployment. He concludes, however, that whilst there were similarities and some collaboration between the nations, there was not enough co-ordination to determine such a model. Meanwhile, and in contrast, Øystein Pedersen Dahlen and Rolf Werenskjold demonstrate that although the three Scandinavian countries took different approaches to NATO membership in the early 1950s, there were actually more similarities than differences in how their governments worked with the press and others to influence public opinion on defence issues. Mari Pajala shows that in relation to Nordvision, where the Nordic countries collaborated in relation to television programmes, there were issues around viewers’ desire for good quality programmes and the associated need to share resources across the nations to make them. However, by contrast there were also concerns about forcing a shared ‘nordism’ on viewers and it was found that it was important to put a ‘positive value to difference’ as much as on similarities and the need to collaborate. Björn Lundberg and David Larsson Heidenblad show in their chapter that interest in the environment started through a campaign in the late 1960s in Sweden to foster interest amongst the youth – this later spread to other Nordic countries and became a crucial area for cooperation. Concern for the environment is just one many areas shown to be associated with the debate around what it means to be Nordic.

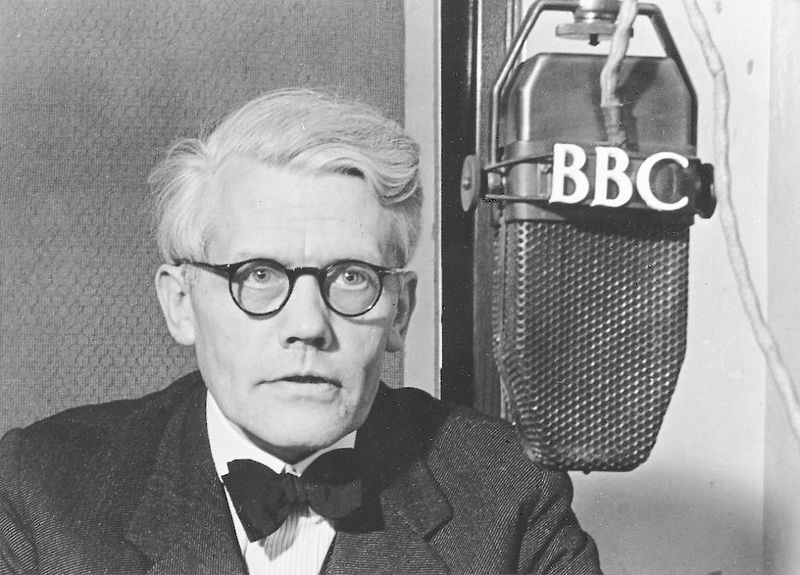

However, the chapters are not just about internal regional debates around what it means to be Nordic. Nor are these studies in how propaganda and persuasion have played out in some kind of Nordic bubble. The book also demonstrates how the Nordic countries have interacted with external influence and organisations. There are many examples of this. For instance Laura Saarenmaa analyses East Asian (Chinese and North Korean) propaganda on Finnish TV during the Cold War (alongside that from other nations around the world); Elisabet Björklund explores how anti-abortion campaigns in Sweden utilised images from the USA, between campaigners in the two countries; Emil Eiby Seidenfaden studies Danish journalists in London becoming propagandists such as on the BBC Danish Service; and Emil Stjernholm explores the work of the American Office of War Information (OWI) in Stockholm during the Second World War. Stjernholm, for example, shows that Stockholm was a centre of propaganda and espionage that attracted many ‘actors’ from outside the country. The OWI operated in a more subtle way in contrast to German attempts to influence Sweden. For example, material such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator was circulating in the country even though the film was not formally approved.

The book also shows that the Nordic nations have found ways to promote themselves and what they have to offer to the wider world. Thomson demonstrates, for example, how beer (notably the Tuborg and Carlsberg brands) was used as a way to promote Denmark abroad and explores what this meant for Denmark’s international reputation. Similarly, in some ways, Melina Antonia Buns and Dominic Hinde argue that in more recent times ‘the Nordic way’ on environmental issues has been used successfully as a brand to promote a certain clean-living lifestyle. This ‘Nordic way’ is presented as having a benefit to the wider world. They argue that this has existed for several decades, right up to the recent UN COP26 in Glasgow (and presumably also seen at this year’s COP27 in Egypt). The interrelationship of the Nordic countries’ approach to development aid and work with the United Nations, and associated interactions with public opinion around aid and what it means to be Nordic, is further explored by Lars Diurlin.

Editors of volumes such as this inevitably must make decisions about what to include and leave out and clearly not every aspect of propaganda and persuasion in the Nordic nations could be covered here. However, I would perhaps have liked to have seen somewhere a mention of the Sámi people in the book. The Sámi inhabit a vast swathe of northern Norway, Sweden and Finland (as well as parts of Russia) and therefore cross the borders of a number of the countries being studied. Given the book considers identity-creation as a key part of the study of propaganda, understanding the interactions between Nordic propaganda and the Sámi people seems an area that would be ripe for examination. Perhaps there has been little interaction, but that in itself would be an interesting story about the relationship between minorities in the Nordic countries and nation-building, and whether the Nordic model, if it exists, is an inclusive one.

Nevertheless, the book is highly readable and illuminates numerous case studies which are not well known, particularly outside of the Nordic countries. It is an enjoyable volume and one which brings new insights and analysis to a fascinating topic which go to the heart of debates around what it means to be of a certain identity, where differences can still exist, and how this can manifest in multiple different media forms and interactions. I would definitely recommend downloading it and enjoying the ‘smörgåsbord’ of examples of propaganda and persuasion in the far north of Europe, which hold together well in a single volume. The editors should be congratulated for their achievement in drawing together the volume a little over two years following the excellent conference.

Nordic Media Histories of Propaganda and Persuasion, Edited by Fredrik Norén, Emil Stjernholm and C. Claire Thomson (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022; 345pp; Open Access).

Dr Edward Corse is an Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre for the History of War, Media and Society at the University of Kent. He has co-edited Propaganda and Neutrality: global case studies in the 20th century with Dr Marta García Cabrera which will be published by Bloomsbury in 2023. Emil Stjernholm has contributed ‘Censorship and Private Shows: mapping British film propaganda in Sweden during the Second World War’ to this forthcoming edited volume.

Image Credit: John Christmas Møller broadcasting in Danish by Det Kongelige Bibliotek/Wikimedia, License: CC BY-SA 4.0