Written by Chloe Emmott

Palestine was viewed by most in Britain, and the wider western world, as ‘the Holy Land’, the cradle of Christianity. After Allenby’s victory in 1918 and the creation of the Mandate (1923-1948), the British promoted themselves as worthy protectors of this important heritage for the world, with the press perpetuating propaganda of the British liberating and developing Palestine after ‘it had been ruined by generations of Turkish rule’. (The Scotsman, 31 August 1921).

Despite the celebratory coverage in the British press over Allenby’s victory in Jerusalem, and the new dawn of a renewed Palestine under the British, the average Briton did not have much awareness of the wider political climate in the area. Even the first Director of Antiquities for the Mandate, John Garstang, admitted to his own naïveté surrounding the political situation. In his “In Pursuit of Knowledge”, he states that ‘like many Englishmen at the time I was not fully aware of the political situation.’ However, the value of archaeology and antiquities to the British in Palestine was recognised as being of significant importance, and Garstang suggested that anxieties around the future of Palestine under the Mandate were not solely concerned with economic issues ‘but mainly and more generally upon its religious and historical associations’.

In light of this, after Jerusalem became an Occupied Enemy Territory in 1918, the British military made swift plans to protect antiquities; in one of his first acts as military governor of Jerusalem, Ronald Storrs, set out to ‘secure some rooms’ for antiquities. This collection of antiquities was stored in hundreds of crates which were reported in 1921 by Garstang’s deputy, W. J Pythian-Adams, as ‘ransacked, neglected, and forgotten’ and as having been ‘rescued from oblivion and are in process of re-registration and arrangement.’ However, these objects correlate to a 1910 catalogue of the Ottoman era Imperial Museum of Antiquities, Jerusalem, a copy of which is in the Rockefeller Museum archive and the Palestine Exploration Fund archives, and further archive documents reveal the artefacts were known to be part of a previous collection. This incident became used as one of many examples of British care towards Palestine. The widely reported ‘sacred trust’ in which Britain held Palestine and protected its heritage for the world was little more than propaganda asserting British superiority over their Ottoman predecessors.

The care of antiquities was an issue that gained attention at the highest levels in British society. Around this time Sir Fredrick Kenyon, then the director of the British Museum, would publish a document entitled Britain’s Task and British Opportunity in the Near East: A School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, with an organising committee formed of many important figures in archaeology, including Garstang, and published via the Palestine Exploration Fund. This document directly refers to the ‘imperious duty’ of Britain towards antiquities after ‘the emancipation by Britain of the Near East’. There is also a considerable folder in the National Archives at Kew entitled Antiquities in Ottoman Dominions, Palestine and the Near East: Proposed international control of antiquities, organisation of Antiquities Department at the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, Antiquities Ordinance for Palestine. In addition to being a concern of government, this was a topic covered in the media, with celebratory coverage of archaeology under the new British regime appearing regularly. Archaeologists themselves, including Garstang and W. J. Pythian-Adams, regularly penned articles for newspapers and magazines. This included a series by John Garstang for the Illustrated London News entitled ‘Digging Sacred Soil’, which opens with the sentence

Great Britain has risen to the full measure of her responsibilities in Palestine, both as regards the protection of the historical monuments and sites and the organisation and encouragement of research in the Holy Land.

The impact of these attitudes can still be seen today, particularly in western engagement with archaeology in the Middle East, where the West yet again casts itself as the saviour of a ‘universal’ heritage for the world, with vague notions of heritage often prioritised over people. Yet challenges to these embedded tropes are being raised in the debate over the need to decolonise museums and other institutions, such as the Palestine Exploration Fund for whom Garstang and many other British archaeologists in Palestine worked, and who wrote on the subject in an earlier post in this special issue. The role many western museums position themselves in as supposedly benevolent custodians for a universalist world heritage is at a turning point – perhaps, it can be said, for the better.

Chloe Emmott is a PhD student at the University of Greenwich, researching the history of British archaeology in Palestine. She is especially interested in the development of Biblical Archaeology and the political uses of heritage as part of colonial discourse. In particular, the role of museums and the press in communicating these themes to a wider non-academic audience.

This blogpost appears as part of a special issue guest-edited by Anne Caldwell.

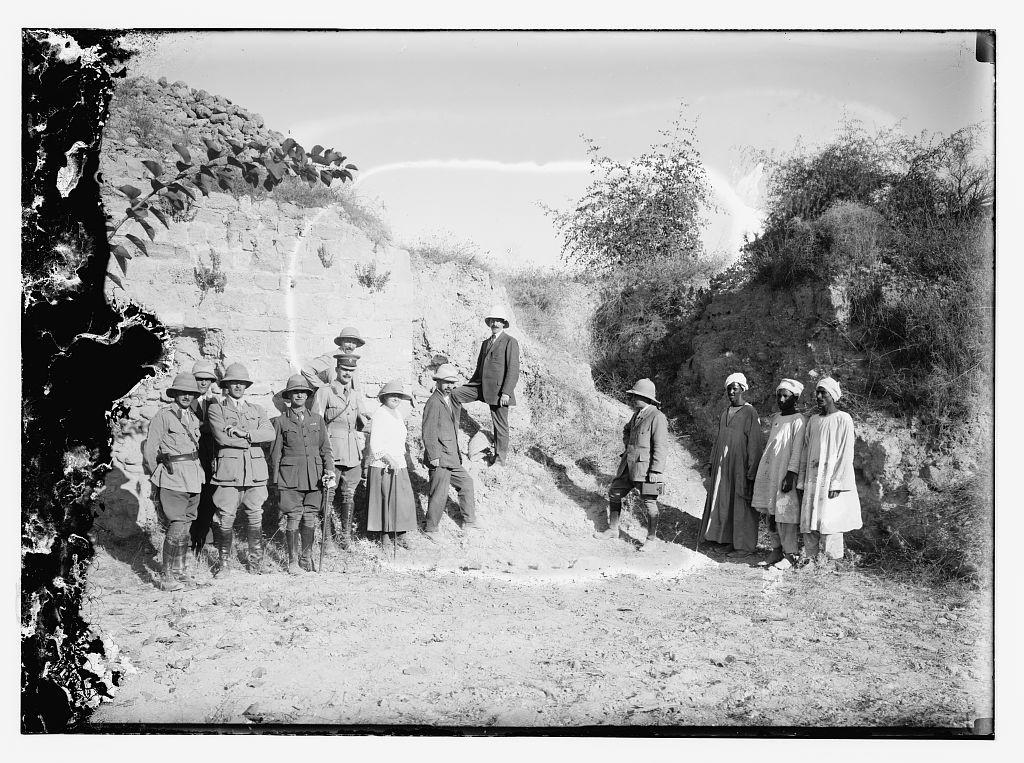

Image Credit: GE Matson, “H.S. in Askalon, Sept. 10, 1920” The American Colony, Jerusalem. Licence: CC BY 2.0

Deeply interesting.