Written by J. Sebastian Browne.

On 26 January 1939, the Catalan capital of Barcelona fell to the advancing troops of General Franco. The occupation of Barcelona was the last major battle of the Spanish Civil War, with the Republic forced into unconditional surrender two months later. The Insurgent offensive against the Republican Army in Catalunya begun on 23 December 1938 prompted the beginning of an exodus that was to result in the flight of 470,000 refugees into France, with the greatest number crossing the frontier in the two weeks that preceded Franco’s closure of the border on 10 February 1939. Republican forces in fact fought a well-organised retreat and much of the army of the Levant passed over into France where it was disarmed and its soldiers incarcerated in concentration camps, with initially little or no shelter or sanitary facilities and treated as prisoners of war.

Nevertheless, not all of the army in the north was able to flee. Concentration camps at Reus and Tarragona were hastily constructed to imprison the 116,000 Republican soldiers and prisoners captured by Francoist forces. By March 1939, seventy new camps had been built to accommodate the large number of captured Republican soldiers in Spain, bringing to a total of 190 the number of Insurgent prison camps at the end of the Spanish Civil War.

The conditions encountered in internment camps both in France and Spain led to widespread disease and high levels of mortality amongst the refugees. For those who stayed on in France the traumatic experience of the Civil War was soon to segue into a continuation of war’s traumatising effects resulting from French participation in the Second World War.

The experience of the interned soldiers and that of the many thousands of civilians including the young and the old subjected to the repressive measures of the Francoist penal system, echoed on one level that of their compatriots in France. They too were subjected to life in unsanitary environments, exposed to the extremes of weather, hunger and work in labour battalions, and it is the medical experience of the vanquished of Spain’s brutal civil war that is explored here.

Despite the warning signs evident in December 1938 that a large number of refugees would make their way to France once the Catalan Front had collapsed, French policy, unwisely, was predicated on a more prolonged Republican resistance followed by eventual mass surrender to Franco’s forces. Therefore, the French authorities did little to prepare for the arrival of nearly half a million refugees on French soil in the space of less than three weeks.

By contrast, the Insurgents had the punishment of the vanquished high on their agenda, and in 1940 there were 270,000 men women and children incarcerated in prisons and camps across Spain. By 1947, 400,000 had passed through what Peter Anderson describes as the Francoist ‘penal universe’. Although French and Spanish policy towards the incarcerated prior to the Second World War had different objectives, cramped and overcrowded conditions and totally inadequate medical cover resulted in widespread disease and death in camps stretching from North Africa to Southern France.

By the middle of February, 180,000 of the near half-million refugees who had fled were interned in just two camps, the overcrowded Argeles sur de Mer and St Cypriens in the French Département des Pyrénées-Orientales. The appalling conditions on the exposed beaches where there was little or no protection against the cold winter conditions, were greatly exacerbated by poor sanitation in the camps and the fact that many of the refugees were suffering from varying degrees of malnutrition as a result of the war. Contaminated water led to dysentery being rife with scabies also a common scourge, and these problems were not made any easier by the most rudimentary of medical cover. There are no reliable figures for the numbers of deaths that occurred in these camps during the first few months of their existence, but somewhere between 15,000 and 50,000 people were to die in these two camps alone.

In the camps themselves, facilities at first were improvised on a makeshift basis. In St Cypriens on 17 February 1939, when construction of wooden barracks first began, seven interned Spanish doctors set up and ran an infirmary which was described as sufficient to serve the needs of a small village but which was open to the elements on one side and had no medicines except for aspirin and bromide. It was nearly three weeks after the opening of the camp at Argeles before more organised efforts were made at looking after the inmates, and a Catalan refugee and Doctor, José Pujol, stated that the only external help that was allowed during this period were daily two-hour visits.

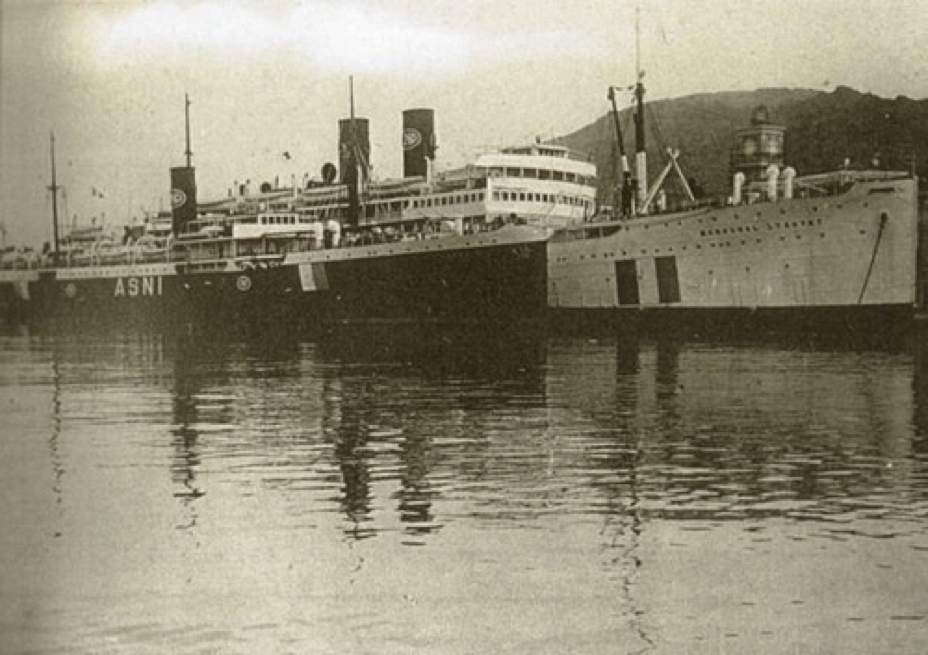

It was not until the beginning of April 1939 that each camp had an infirmary/hospital, but these were wooden barracks with limited facilities. There were some hospitals that provided for the treatment of sick and wounded Republican soldiers, such as the hospitals of Saint-Jean and Saint-Loius in Perpignan, and the hospital at Amélie-les-Bains which also cared for children with air-raid injuries, nevertheless much suffering could have been avoided by directly employing Republican medical exiles. However, the hospital ships Maréchal Lyautey and the Asni, moored at Port Vendres, and the Providence and Patria moored at Marseilles provided a maximum capacity of 4,410 beds, and it was on these ships that 6,000 Republican wounded soldiers were treated. Conditions, nevertheless, were far from ideal with the hold and cargo spacing below deck on the Maréchal Lyautey holding 800 wounded in cramped conditions, and the Asni which was moored alongside described as having 800 wounded under treatment on a ship which only had a capacity of 600 beds.

The hospital ships Maréchal Lyautey and the Asni, moored at Port Vendres, 1939. Image credits: http://www.flickriver.com/photos/jordipostales/2864083690/

The hospital ships Maréchal Lyautey and the Asni, moored at Port Vendres, 1939. Image credits: http://www.flickriver.com/photos/jordipostales/2864083690/

For a number of reasons, the hospital ships also served as quarantined spaces. There was a perceived need to isolate those seriously ill with contagious diseases so as to avoid epidemics although the majority of patients appear to have been surgical cases. Those treated were soldiers and thus prisoners of war and therefore the ships were also places of confinement. However, with an estimated 30,000 sick and wounded refugees in need of hospitalisation, the total number of hospital beds available across France were far from sufficient, and the death rate rose as a result. Additionally, the hospital ships were only in operation for a brief period and the soldiers once treated were discharged back to the camps.

What differentiated Spanish spaces of internment from their French counterparts was their use by the new regime as places where the defeated were subjected to what Helen Graham describes as ‘a sustained and brutal attempt to reconfigure their consciousness and values’.

The Prison of Nursing Mothers of Madrid exemplified this approach. Set up in July 1940 to relieve the strain on the prison of Las Ventas the involvement of María Topete Fernández who later became its director, and whose own experience of ‘traumatic’ captivity by the Republicans served as validating credential for her adhesion to the new regime, was to have dire consequences for many of the inmates.

María Topete (left) with children at The Prison of Nursing Mothers of Madrid, 1943. Image credits: http://todoslosrostros.blogspot.co.uk/2008/06/los-nios-perdidos-del-franquismo.html

María Topete (left) with children at The Prison of Nursing Mothers of Madrid, 1943. Image credits: http://todoslosrostros.blogspot.co.uk/2008/06/los-nios-perdidos-del-franquismo.html

María Topete, only allowed mothers one hour’s access to their children each day, and it was during this time that the children were provided with their only meal, a thin gruel that often contained insects. The rest of the time the infants were placed in cots in the courtyard regardless of the weather and many died of exposure and bronchitis and pneumonia due to the damp caused by the hospital’s close proximity to the River Manzanares.

These deliberate acts of separation were common in prisons throughout Spain. María Aranzazu Vélez de Mendizabal ran a particularly brutal regime at the prison for women at Saturrarán in the Northern Spain. One hundred women and fifty children died of illness at Saturrarán, and this experience was replicated by women and children across Spain during the early years of Francoism.

Ideas of collective punishment of the Republican defeated, and which often included the castigation of whole families was high on the agenda of the new regime, and the autarkical policies followed by the new Francoist dictatorship, led to 200,000 people dying of starvation in Spain during the 1940s. If the majority of these deaths were attributable to famine, endemic diseases that once again swept across Spain and which found fertile breeding grounds in the overcrowded penal establishments of the new regime, also contributed to the overall number of deaths, with even minor infections capable of killing those whose diets were largely devoid of protein, vitamins and fats.

During this period there were epidemics of typhus, a disease which had largely been controlled on both sides during the Spanish Civil War, with 4,000 people alone affected in Málaga in 1941. Tuberculosis (TB), malaria and diarrhoea (which had a number of causes) also contributed to the large rise in mortality, with diarrhoea the cause of 60,000 deaths amongst the Spanish population during 1941.

Confinement in institutions alone meant that people whose health had been compromised by war were exposed to contagious illnesses that could often be fatal. The women’s prison in Segovia founded in 1946, was the destination for political prisoners from all over Spain, including those suffering from TB. As an institution, it had functioned since 1943 as a tuberculosis sanatorium (if only in name) despite later converting to penitentiary use, and a number of ‘healthy’ inmates died due to being exposed to and contracting TB during their time in the institution due to the poor sanitary conditions.

It has been estimated that by the end of 1940, 70,000 of the 280,000 prison population had died as a result of disease, malnutrition or execution, and prisons and prison camps in Spain – to quote Helen Graham – were acutely dangerous up to circa 1947 in terms of overcrowding, lack of hygiene, medical attention and food.

The experience of the hundreds of thousands who found themselves under detention in France and Spain at the end of the Civil War ultimately had much in common. For those who sought refuge in France, their lives were to be marked by imprisonment, forced labour and the German occupation – with many never returning to Spain after the liberation of France. For the vanquished who suffered in the prisons and camps of the Francoist dictatorship, liberation would have to wait, as despite the decline in the prison population after 1943 within Spain the harsh and repressive measures of the Franco regime would continue to take their toll on an undernourished and defeated nation.

Sebastian Browne is an Associate Lecturer with the School of Humanities at Canterbury Christ Church University and a Doctoral Candidate in the School of History at the University of Kent. He was a co-organiser of the conference ‘Crossing Borders: The Spanish Civil War and Transnational Mobilisation’ in 2016.

Title image: Soldiers with arms encased in plaster of Paris crossing over into France, February 1939. Image credit: http://www.flickriver.com/photos/jordipostales/2875988689/