Written by Charlie Hall.

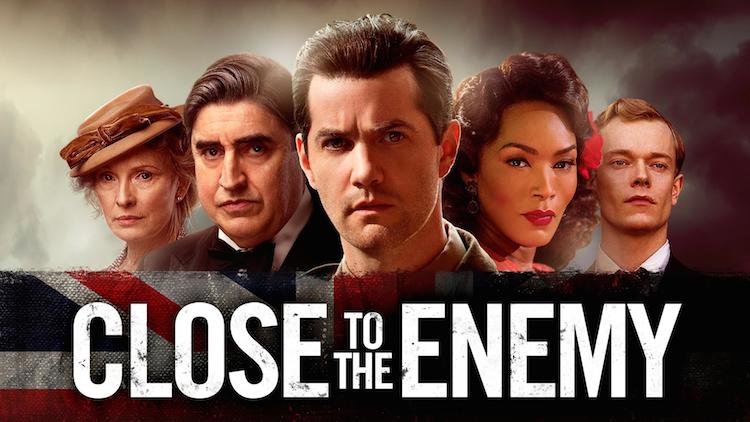

Close to the Enemy is a seven-part British TV drama series, penned by screenwriter Stephen Poliakoff (Dancing on the Edge, Capturing Mary), which aired on BBC2 throughout November and December 2016 (fear not, this is a spoiler-free article!). Set in Britain directly after the Second World War, Close to the Enemy explores many themes which were relevant to post-war British society, including the mental health struggles of returning servicemen, the flourishing black market and the surprising continuation of activities by British fascists. However, its core storyline centres on attempts by military intelligence officers, primarily Captain Callum Ferguson (Jim Sturgess), to recruit a German jet engine expert, Dieter Koehler (August Diehl), to work for Britain in the new Cold War era. The aim of this article is not to provide a review of the series but rather to examine the historical truth of this controversial programme of recruitment, which provides so much of the dramatic substance in Poliakoff’s script.

Firstly, it is important to note that, on the whole, the central concept of Close to the Enemy does hew very close to the truth. Britain did indeed seek to employ German scientists and technicians after the fall of the Third Reich; a policy which had its roots in the widely-held perception that Nazi scientific achievements outstripped Allied equivalents during the war, and while this was true in some areas, such as rocketry and chemical warfare, in others it was swiftly discovered to be false, such as nuclear physics. Jet engine technology, the speciality of Dieter Koehler in Close to the Enemy, is a more complicated example – in many ways, Britain’s domestic wartime jet research was superior to the Germans’, but it was still a subject in which the British were feverishly interested after the war. It is worth pointing out also that the recruitment of experts was only one element of a wider programme of ‘exploitation’ which Britain (among others) conducted in post-war Germany – other aspects included the investigation of laboratories and factories, the confiscation of documents and prototypes, and the wholesale evacuation of equipment and facilities.

Britain was in a position to enact these schemes on account of its post-war role as one of the four occupiers of German territory, along with the United States, the Soviet Union, and France (though it should be noted that other former Allied and neutral countries, such as Spain and the Netherlands, also took part in exploitation, albeit on a smaller scale). Naturally, as the number of really significant German experts was obviously limited and as Cold War divisions deepened, there was competition (often fierce) between the Allies for the ‘brightest lights’ of German research. The British were especially concerned about letting any of these individuals go over to the Soviets, who they perceived as their likely future adversary, but there were also frequent contentious incidents involving France and the United States (whose so-called ‘Paperclip’ programme is perhaps best-known today). All these nations wished to use German expertise to strengthen their position on the world stage in the post-war reconfiguration of the geopolitical power structure and this drove much of the recruitment, something which Close to the Enemy highlights accurately.

Having established that the main endeavour at the heart of the series was a real one, it is now worth considering some elements which are not portrayed wholly honestly in Poliakoff’s script. One of these is the conflict between the efforts to recruit Koehler and ongoing investigations into Nazi war crimes. The potential for a real clash of this nature was of course present – some of the scientists targeted were definitely implicated in atrocities committed by the regime, such as human experiments or slave labour in the concentration camps (perhaps the most famous example is Wernher von Braun; the German rocket supremo who had connections to the appalling conditions in the Dora underground weapons factory but who found post-war employment remarkably easily in the USA, and later became a hero of the American space programme) – but in reality, conflict rarely materialised. In fact, many of the exploitation investigators often recommended that the men they’d interrogated be tried for war crimes, and were more than willing to share any potentially incriminating evidence they’d gleaned. However, it should also be noted that a Nazi past did not preclude a scientist from obtaining work in Britain after the war – in March 1946, the Lord Chancellor, William Jowitt, declared to the House of Lords, ‘I am willing to risk their being Nazis – and I think they probably are – so long as they are highly skilled technicians who will teach our people something which they did not previously know.’

Another aspect of truth which has been sacrificed for the purposes of dramatic effect in Close to the Enemy is the way in which German experts were brought to Britain. There were practically no examples of coercion being used, and no scientist was dragged across the Channel against his will. In fact, the instructions issued by the Government expressly forbid such treatment, though this did not mean the scheme wasn’t open to contemporary criticism along these lines, including one accusation of British agents utilising so-called ‘Gestapo methods’. The wire-tapping which Close to the Enemy depicts did take place occasionally but that was often the extent of underhand tactics – for example, families were not exploited to secure the services of a specialist, in fact scientists were not allowed to bring their loved ones over to Britain until they’d been working here for six months (so, in reality, Koehler’s daughter would not have accompanied him from Germany). Such extreme efforts as hauling an intransigent German expert out of bed to force him to work for Britain were not needed, because the scientists were rarely reluctant to take up work abroad; after all, the shortage of housing, food and jobs in Germany (any military research on German soil was totally forbidden too) made foreign employment seem really quite attractive.

Smaller deviations from the truth abound as well, such as the decision to set much of the action in a vast and largely empty (and thus conveniently atmospheric) dilapidated hotel (most of the interrogation and recruitment efforts actually took place at specially requisitioned sites such as a school in Wimbledon and a large private home in Hampstead), but these can easily be forgiven as acceptable uses of dramatic license. What is more concerning then is that, while Close to the Enemy will hopefully encourage viewers to find out more by accessing more reliable sources (there is a wealth of popular history available on post-war exploitation), the dramatic embellishments present a dangerously warped version of the truth, which casts largely inaccurate aspersions not only on the German scientists who were recruited but also on the British agents who were responsible for this task. Once again, we are presented with a cautionary tale about historical television dramas which must be taken with a generous pinch of salt and never at face value.

Further Reading

- John Gimbel, Science, Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Post-War Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990)

- Paul Maddrell, ‘Operation Matchbox and the Scientific Containment of the USSR’, in Peter Jackson and Jennifer Siegel (eds.), Intelligence and Statecraft: The Use and Limits of Intelligence in International Society (Westport: Greenwood, 2005), pp. 173-206.

- Andrew Nahum, ‘”I believe the Americans have not yet taken them all!”: the exploitation of German aeronautical science in postwar Britain’, in Helmuth Trischler and Stefan Zeilinger (eds.), Tackling Transport (London: Science Museum, 2003), pp. 99-138.

- Norman Naimark, The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), esp. pp. 205-250.

- Michael J. Neufeld, ‘The Nazi Aerospace Exodus: Towards a Global, Transnational History’, History and Technology, 28 (2012), pp. 49-67.

- Douglas O’Reagan, ‘French Scientific Exploitation and Technology Transfer from Germany in the Diplomatic Context of the Early Cold War’, International History Review, 37 (2014), pp. 366-385.

- Matthew Uttley, ‘Operation Surgeon and Britain’s post-war exploitation of Nazi German aeronautics’, Intelligence and National Security, 17 (2002), pp. 1-26.

Charlie Hall is a research associate and assistant lecturer in the School of History at the University of Kent, and submitted his PhD thesis on British exploitation of German science and technology after the Second World War in August 2016. Email: ch515@kent.ac.uk

Image credits: www.bbc.co.uk