Written by Florian Steger and Maximilian Schochow

After the Second World War, Russian officials introduced the Soviet healthcare system in the Soviet Occupation Zone (SOZ), which later became the GDR. Orders 25, 30, and 273 of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SMAD), while demanding “to fight people who belong to the German population and suffer from venereal diseases” (VDs), included measures designed to contain the spread of VDs, which were based on the Soviet model. The Soviet health instructions against VDs included the training of dermatologists and venereologists, the compulsory hospitalisation of sufferers, as well as the establishment of protectories. After the German Democratic Republic (GDR) was founded in 1949, the SMAD commands 25, 30, and 273 were replaced by the East German law regarding the “Regulation to Prevent and Fight Venereal Diseases” at the beginning of the 1960s.

This new regulation was put into effect on 23 February 1961 and partly followed the preceding SMAD decrees, such as the multilevel procedure of compulsory hospitalisation for VD sufferers and incarceration into an isolated ward within the hospital. On the grounds of this regulation, all people who had resisted or eluded medical treatment, those who had a record of repeated infections with VDs, and those who were under the suspicion of promiscuous behaviour were to be hospitalised. If these people evaded hospitalisation, they were at risk of being institutionalised and incarcerated in a VD ward that had the characteristics of a prison. In the following years, about ten of these wards were established throughout the GDR—including Berlin, Dresden, Erfurt, Frankfurt (Oder), Gera, Leipzig, Rostock, and Schwerin.

Elsewhere, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) created institutions similar to the GDR closed VD hospitals after the end of World War II. In the beginning, the legal provisions to fight sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in the Allied-occupied Western Zones showed differences across the three zones. After the FRG was founded in 1949, however, the coercive measures against people suffering from an STD were uniformly regulated by the “Law to Fight Sexually Transmitted Diseases”, enacted on 23 July 1953. Other historians have examined closed hospitals for skin diseases and VDs within the Port cities of Bremen and Hamburg; however, in our article, we focus on the venereology ward in Halle (Saale) because this station served as a model for all other venereology wards founded in the GDR in the following years.

The closed venereology ward in Halle (Saale) was mainly established with the purpose to educate “asocial” women, as well as women suffering from venereal diseases, which the 1963 preamble of the House Rules specified as the following:

“By means of education, it needs to be accomplished that, after leaving the hospital, the citizens will come to respect the rules of our state, display a good work discipline, and—in their behaviour in our society—follow our state’s principles regarding the socialist coexistence of citizens”.

The ward had 30 beds in several dormitories, an examination room, and an office; entrance doors were barred, and windows were equipped with iron bars. According to the house rules and the spatial isolation of the girls and women, visits from relatives, friends, and acquaintances were prohibited.

Girls could be admitted in Halle (Saale) from the age of twelve, and most of them were between 14- and 16-years-old. The women came from all social classes and had a wide variety of educational backgrounds. They lived in the city or the district of Halle (Saale)—and some were brought to the Poliklinik Mitte (Polyclinic Central City – the name of the clinic in which the locked VD ward was based) from neighbouring districts. It is not known whether or not men were admitted and treated in prison-like venereology wards in the GDR as well. In defiance of the 1961 GDR regulation, girls and women who were arrested by the transport police at train stations for “loitering,” were often sent directly to, and incarcerated in, this venereology ward. Moreover, girls and young women were also transferred from Jugendwerkhöfe (Youth Reformatories) and other correction facilities to this ward in Halle, and sometimes parents who did not get along with their daughters also sent them there. A denunciation or the mere suspicion of VD often resulted in a girl or woman being admitted directly to this institution.

Upon admission, the women and girls had to undress, turn in their valuables, wash themselves (at times with shaving lotion), and dress in institutional clothing (a blue gown). During this procedure, they were kept under surveillance by the medical and nursing staff, often also by the quarter chief. Afterwards, their case history was taken by the warden, in the course of which the women were asked questions about their sexual partners. A gynaecological examination was performed as well. In fact, gynaecological examinations took place every day without consultation or the consent of the girls and women. In order to carry out the examination, the girls and women had to climb on a treatment chair. To take a smear test, a glass tube was vaginally inserted, which frequently caused injuries and bleeding upon removal. Defloration occurred during first-time swabs. If the swabs were negative when administered for the first time, the women were injected with a fever-inducing drug (likely Pyrexal) in order to trigger a possible infection and reveal a gonococcal infection. The injections frequently caused nausea, high fever, and recurring seizures all over the body.

Examinations were used above all to frighten and discipline girls and young women. After all, from the total of 235 girls and women who were institutionalised at Halle’s venereology ward in 1977, only 30 percent actually suffered from VDs. In about 70 percent of the cases, no medical indication existed – meaning that no medical conditions could be detected. Nonetheless, the treatment at the venereology ward usually lasted four to six weeks in most cases. The ward’s daily routine was strictly regulated: the women had to get up before six o’clock in the morning; they washed, were subjected to the daily gynaecological examination, and had breakfast. Part of the educational program to become a “socialist personality” included work therapy, in which all eligible women had to participate. They could be enlisted to clean up patient and hospital rooms, as well as other places. Some were appointed to the kitchen, whereas others performed unskilled jobs in the laundry room. Lunch took place in the common room at noon, after which the women were left to their own devices. In the evening, absolute silence was ordered from 9 pm onwards.

The closed ward was dominated by a hierarchical terror system, which was determined by the house rules and implemented by physicians, nurses, and the quarter chief. The system functioned on the basis of commendations and disciplinary measures. Forms of commendations included additional smoking permissions, the annulation of a house penalty, and written praise, whereas disciplinary measures meant additional work therapy, as well as spending the night on a stool. Another punitive measure was to deny a girl or woman a smear test, which ultimately meant prolonging her stay in the ward, as each inmate had to have 30 negative smear tests in order to be released. All of these punitive measures were frequently applied.

The ward’s superintendent was known to be impersonal and in his interaction with the girls and women he made them feel deprived of their individuality. The medical and nursing staff abused the girls and women by inflicting pain on purpose during the smear tests. Moreover, the quarter chiefs maintained the internal terror system as those patients were in charge of arranging fatigue duty, leaves of absence, and auxiliary activities. At the same time, the quarter chiefs had to oversee the punishments (24 hours of isolation, sitting on a stool, sleep deprivation, and revocation of smoking privileges).

Many of the girls and women who, prior to the initial gynaecological examination at the venerology ward, had had no sexual intercourse were deflowered. As a result of the injection of the provocation agent, many women complained about nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, fatigue, headaches, long-term paralysis and shivering fits. Moreover, the majority of contemporary witnesses describe long-term damages, from which they still suffer today. Among these long-term consequences is an overall anxiety regarding gynaecological examinations or physicians in general. A lot of women still suffer from insomnia, sexual reluctance, and incontinence. Many biographies tell the story of a certain inability to establish a functioning long-term relationship, which might be the result of the stay in the locked venerology ward. A contemporary witness reports lived in frequently changing partnerships. Although these relationships resulted in children, she was unable to establish a lasting bond with the respective partner. Other women report that they have remained childless.

Several women resisted the medical and the social treatment by the staff. However, this resistance was either suppressed by the nurses or by the quarter chief and thus, to put it in other words, the physical abuse occurred frequently. One instance, for example, that happened in the locked venereology ward in Halle (Saale) and became public in the late 1970s, resulted in the dismissal of the institution’s superintendent and, eventually, the closure of the ward in Halle (Saale) in 1982. Only a few cases are documented that give evidence that the girls and women’s relatives or the medical and nursing staff opposed the internal terror system. To this day, women are still coping with the long-term effects of their forced institutionalisation in the closed venereology wards, such as being afraid of gynaecological examinations in particular and physicians in general, as well as suffering from sleep disturbances, impaired sexual desire, incontinence, bonding deprivation, and childlessness.

Based on conservative estimations, about 4,700 girls and women faced compulsory hospitalisation in the closed venereology ward in Halle (Saale) during the twenty years of its existence. The girls and women did not receive an outpatient treatment with known antibiotics but were mostly institutionalised in defiance of the legal provisions. They were isolated against their will and without consultation for at least four weeks in order to be taught to act as “full members of society” (House Rules, 1963). In this hierarchically organised terror system, the girls and women had to perform daily tasks on the ward and in other departments of the polyclinic. We are currently working on two comparative studies: the first study focuses on the locked venerology wards in the GDR and the FRG, and the other one examines similar institutions in Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

Explanatory note:

Geschlossene Venerologische Stationen = ‘Closed Wards for Venereology’, describe departments within East German health clinics, specialised in sexually transmitted diseases, which were segregated and often had the characteristic of a prison.

Florian Steger is Professor, the Director of the Institute of History, Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine, and the Head of the Ethical Commission at the University of Ulm, Germany. He studied medicine, classical philology and history, and published extensively about various periods within the history of medicine.

Maximilian Schochow is a research assistant at the Institute of History, Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine at the University of Ulm, Germany. He studied theatre and political science, before he moved into the natural sciences, writing his PhD about the systematics of intersex and subsequently started his career as a medical historian.

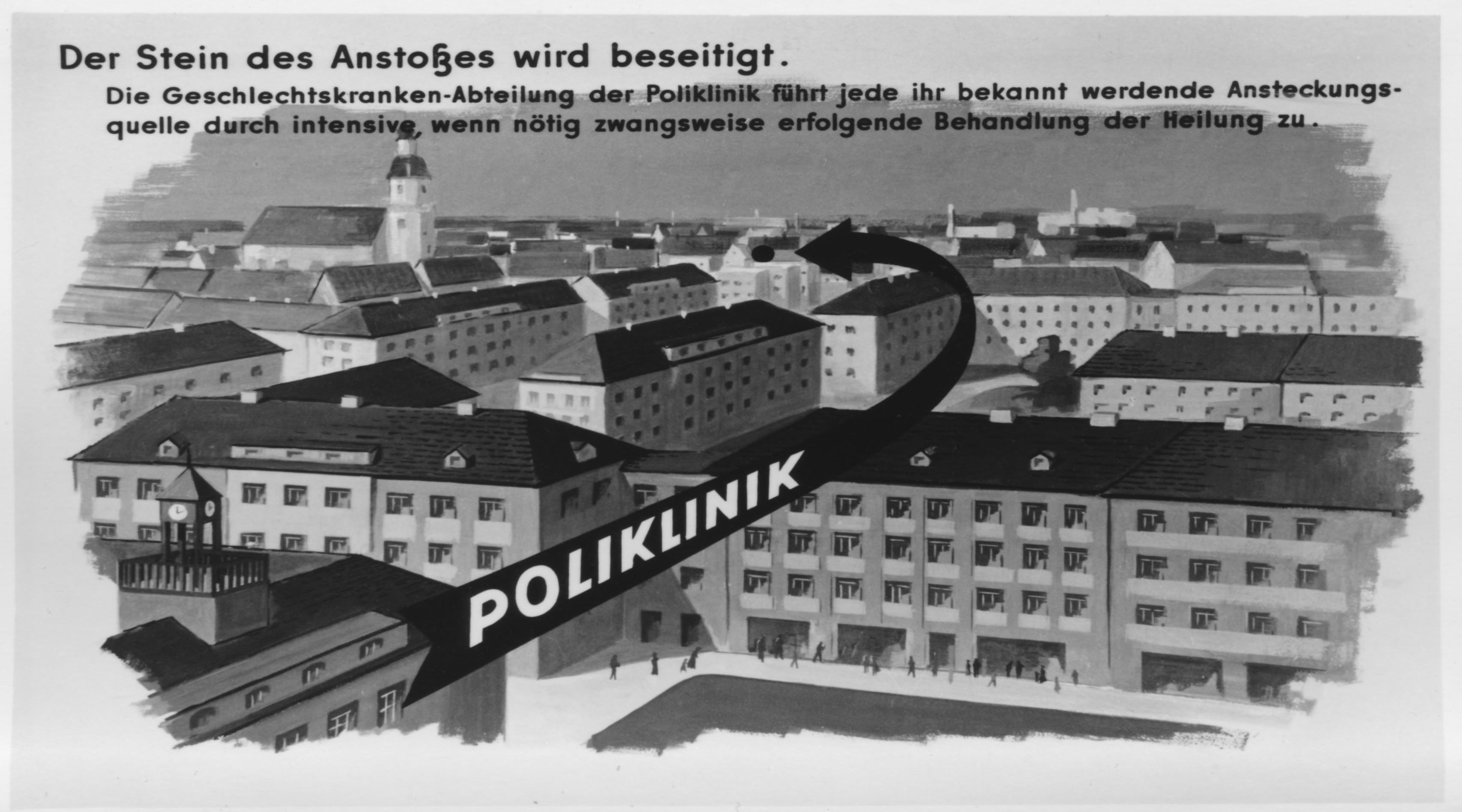

Title Image:

“The stumbling stones will be removed. The STD Department of the Polyclinic intensively treats every known source of infection; if necessary, even with the means of force”. Poster was part of an exhibition by the German Hygiene Museum Dresden about the prevention and treatment of STDs in 1954.

Credits: Deutsches Hygiene Museum Dresden (DHMD), Lep. 14, Bl. 18.

Further reading:

Florian Steger and Maximilian Schochow, Traumatisierung durch politisierte Medizin. Geschlossene Venerologische Stationen in der DDR (Berlin: MWV Medizinisch Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 2015).