Written by Neil Pemberton.

If anyone reading this blog has heard of the disease toxocariasis, it is most likely through anti-excrement campaigns run by local councils to remind dog owners to pick up after their dogs. Toxocariasis is a rare disease caused by accidentally swallowing the microscopic eggs of the canine-borne worm Toxocara canis shed in the faeces of infected dogs, causing – in some cases – blindness and asthma. An embedded ritual within the choreography of dog-walking, ‘scooping the poop’ functions as a form of environmental purification designed to transform public space into a clean, safe and sanitised zone, by removing potentially dangerous faecal matter.

As part of a larger project exploring the history of the etiquette and public persona of the hybrid figure of dog-walker, my current work focuses on concerns about dog dirt and disease were rehearsed for the first time in public health literature and propaganda. When alarms about the dangers of toxocariasis were first raised during the 1970s, generating a fully-fledged public health scare, many dog owners did not pick up after their dogs, nor were they compelled to by the local or national government. Compared with today, then, the country’s public parks, grass verges and streets would have been far messier.

Responding to widespread public concerns, many councils across the country made strident attempts to prevent the accumulation of dog faeces in parks by banishing dogs from such spaces, at once calling into question the right of owners to walk their canine partners in public space and the very status of the dog as a companion animal. However, the panic did not transform the nation’s parks into dog-free zones. Nor did the toxocariasis scare necessarily push the country towards the modern regime of picking up. For few mentioned picking up as a realistic solution to the canine faecal crisis, and there was little appetite in political circles to emulate New York Mayor Ed Koch’s 1978 ‘Pooper Scooper Law’: an indigenously generated sanitary revolution, which grew out of that city’s attempts to combat its environmental problems.

For me, the 1970s toxocariasis scare provides a lens with which to explore the role played by disgust in public health campaigns and propaganda. Medical scientists, politicians, reporters, parents and members of the public sought not only to provoke but also to harness the dark emotion of disgust as means to redefine canine faeces from a widely tolerated, albeit unpleasant, nuisance to a fearsome health hazard that should no longer be tolerated in public spaces. Cultural critics, historians, and philosophers remind us that far from being natural and self-evident, disgust is an emotion that is socially determined, learned and then embodied. As the philosopher Martha C. Nussbaum has thoughtfully observed, ‘Disgust in its “thought content” is typically unreasonable, embodying magical ideas of contamination, and impossible aspirations to purity, immortality, and nonanimality that are not just in line with human life as we know it.’[1]

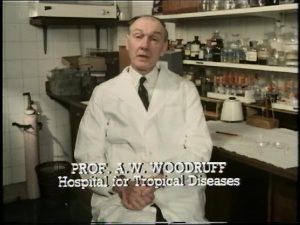

The key piece of health propaganda that connected worms, dog dirt and disgust came in the mid-1970s. In 1975, Thames Television screened an hour long-long documentary entitled The Case Against Dogs, communicating the health dangers of dog fouling and the risk of toxocariasis, which hitherto had been limited to the pages of medical journals. The documentary described the results of the investigations carried out by the renowned medical scientist Professor Alan Woodruff. Interviewed in his laboratory, Woodruff explained how he had retrieved and analysed infected soil samples from public parks across the country. However, crucially, the documentary served not only as a translation of Woodruff’s medical work but alsoas an imaginative elaboration within contemporaneous registers of disgust.

This televisual-propaganda narrative attempted to make the presence of dog faeces in public spaces, especially in public parks, newly disgusting and shocking by drawing attention to the perceived nature and biology of Toxocara canis. Short film clips were presented a single microscopic larva with its alien-like physiology hatching and wiggling out of its shell. The image of a single worm – an autonomous life form living outside of human perception and control – was used to underscore the species’ monstrous multiplicity and voracious reproduction. As the voice-over worryingly explained: ‘Each Toxocara worm produces a great number of microscopic eggs. These simple near indestructible organisms are so small that a smear of dirt contains thousands of them’.

What was so striking about the documentary was its unleashing of disgust against not only Toxocara canis but also against other targets: there was an explicit willingness to attach disgust to dogs and, by association, their human companions. Footage showing children playing on parks soiled with faeces and where dogs freely wandered was joined by footage of children cuddling and touching dogs. By deploying the long-established sentimental image of the innocent child victim, the documentary endeavoured to reveal the dark side of the companion species relationship and to stigmatise dogs as impure, dangerous and dirty to the touch.

The Case Against Dogs thus fostered an atmosphere of suspicion against dogs, the immediate consequence of which was councils’ attempts to ban dog walkers from public parks. However, it also generated a counter propaganda strike launched by the dog lobby, one that associated dogs with health and well-being rather than parasitism and dirt. No one opposed the toxocariasis scare more and more successfully than the charitable organisation PRO-Dogs led by Lesley Scott Ordish. An organisation that was set up in the wake of public reaction to the Thames documentary, PRO-Dog’s main aim was to challenge what it perceived as an intensifying ‘anti-dog hysteria’ that had gripped the country and pointed to the dangers of the combined rhetoric of disgust and disease. The organisation launched an alternative propaganda campaign, printed free literature, brought together breeders and vets and lobbied the government. The charity also politicised ordinary dog owners, by establishing local branches to help coordinate protests against attempts made by local authorities to expel dogs from parks.

For PRO-Dogs,the problem with The Case Against Dogs was that it narrowly focused on the dog and wrongly assumed all dogs to be seedbeds of parasitism to be kept under constant surveillance. What was needed, according to PRO-Dogs, was a plan that dealt with both dogs and their owners at many different levels, and first and foremost on education, not coercion and legislation. They accused the anti-dog lobby’s ‘propaganda’ of prejudicing the question of dog-fouling to avoid dealing with the real issues and called for the abandonment of the politics of disgust and hate.

However, the desperation of some dog lovers to prove their dogs were ‘clean’ and ‘innocent’ manifested in anti-human sentiment as virulent as anything that was levelled against the dog. Some dog owners, for example, claimed that if their children developed toxocariasis parents should be blamed for not supervising their kids properly, not the ‘innocent’ dog. The 1970s public drama that arose around toxocariasis and dog faeces demonstrates the problems resulting from the use of disgust. Emotions ran high and pushed people apart, bringing into being two diametrically opposed camps labelled ‘dog-lovers’ or ‘dog haters’.

As this research project develops, I’m planning to trace the resonance of this political binarism and hardened rhetoric in discussions of the risk management of dogs and their faeces into the 1980s and 1990s. I suspect that as a consequence of the polarising effects of the 1970s toxocariasis scare, parliament was reluctant to get involved in matters dealing with dog fouling or even contemplate an American-style ‘poop scoop’ revolution. It was not until 1996 that Britain introduced the Dogs (Fouling of Land) Act and ushered in the modern regime of bins, signs, posters, and legally sanctioned fines that placed responsibility on owners to remove dog waste from public spaces.

[1] Martha C. Nussbaum, Hidden from Humanity: Disgust, Shame and the Law (Princeton University Press, 2009), 14.

Neil Pemberton is a cultural historian of medicine and modern Britain at the University of Manchester. He has explored the history of disability, the history of animal-human relations and the history of detection and forensic medicine. His latest book Murder and the Making of English CSI has been recently published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Images from Thames Television documentary: The Case Against Dogs (1975).