Written by Philip Boobbyer.

As Solzhenitsyn saw it, simple truths are always a threat to totalitarianism.

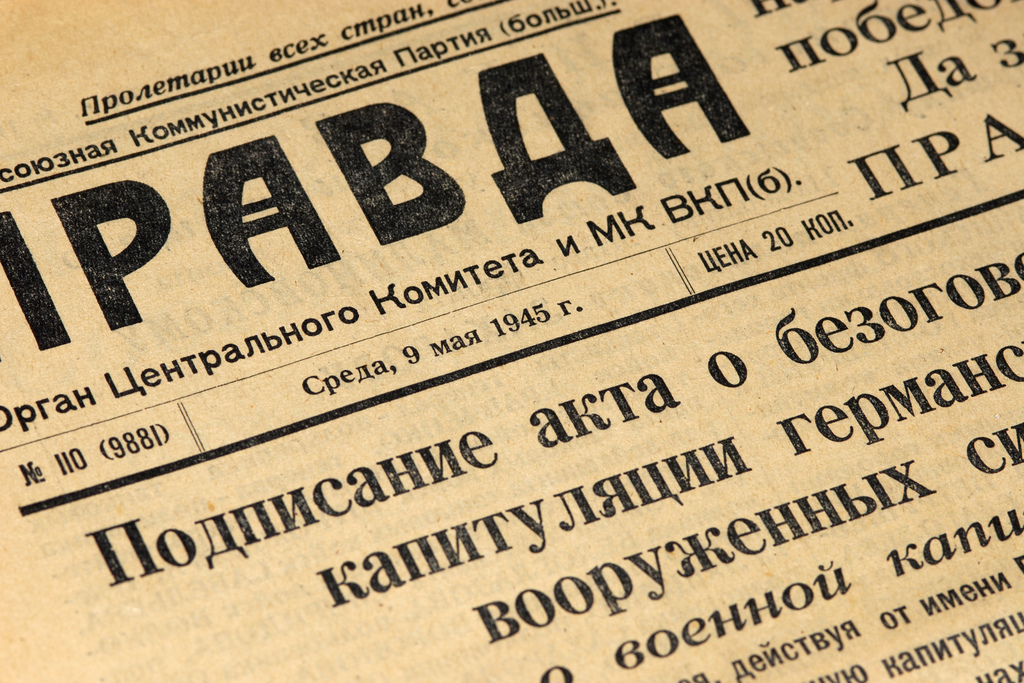

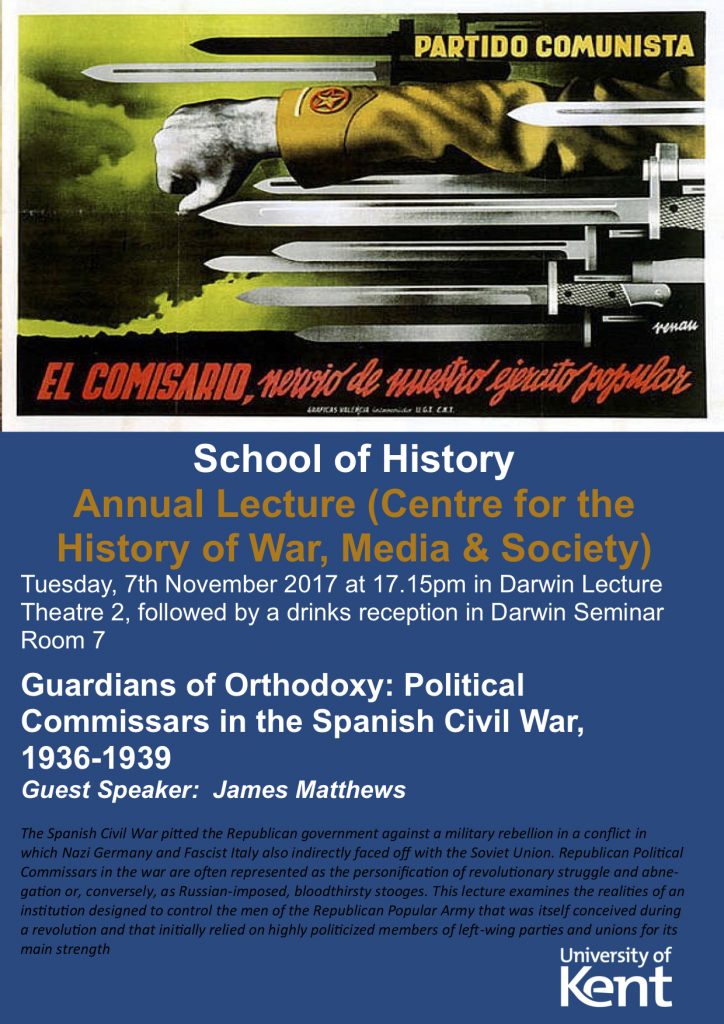

“Fake news” may be getting lots of headlines, but it is as old as the hills. Propagandists have relied on false evidence for centuries. Of course, not all propaganda campaigns are dishonest; indeed many efforts at persuading people of things are laudable. But the phenomenon of fake news and the “post-truth” culture in which it thrives are clearly a threat to democracy, and to the public sphere that democracy depends on to survive.

Everyone has a part to play in pushing back. Most of us probably assume that only other people fall prey to false or exaggerated news stories. This is complacent. Media historians emphasise that propaganda often exploits already-existing trends rather than creating new ones, making subtle use of half-truths as well as outright falsehoods – and it can be much harder to unpick half-truths than to demolish lies.

Leave a Comment