Written by Julian Daggett.

General Allenby, as Basil Liddell Hart observed, was something of an enigma. In the public eye he became both a great and popular First World War general. His war, however, did not start well. The official historian, James Edmonds, held that his career in France was one of ‘gross stupidity’. Allenby was a cavalry officer; at the outbreak of the war he commanded the Cavalry Division and – by late 1915 – Third Army. He also commanded a fearsome reputation, being known as ‘the Bull’ – a rough, headstrong general who just butted forward in a blind sort of fashion. The initial, tactically impressive, triumph of Third Army at The Battle of Arras (1917) almost changed Allenby’s reputation on the Western Front. But the triumph was short-lived; the fighting soon turned into the familiar attritional grind and Allenby reverted to type. Three of his divisional commanders broke ranks and complained to Haig about Allenby’s murderous orders. In June 1917 Allenby was recalled to Britain.

Curiously, what awaited Allenby was a meeting with Lloyd George that would transform the General’s fortunes, and his reputation. Lloyd George sought a new commander for the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF), one with an offensive spirit to replace the ‘lacklustre’ General Murray. It was in the Middle Eastern theatre, specifically Palestine, that the Prime Minister believed a decisive victory could be won over Germany’s ally the Ottoman Empire. The morale boosting effect of winning Jerusalem as a ‘Christmas present for the British nation’ would be significant. Allenby acquiesced to Lloyd George’s offer – although believing it to be a command in a peripheral theatre of the war he was promised all the materiel he required for success. His success was to be astonishing. ‘The Bull’ appeared to be transformed into a master tactician who won, through the use of manoeuvre and mobility, not only Jerusalem but a vast swath of the Ottoman Empire. This transformation has rather perplexed historians, although Allenby’s public accepted his greatness from the outset.

Allenby only made his mark upon popular memory following his appointment to the EEF. His subsequent military successes – Third Battle of Gaza and Battle of Megiddo – thrust him (literally) onto the public stage. The Palestine theatre, the Holy Land, was a gift to journalists, writers, photographers and film makers. The nature of the warfare – strategy, manoeuvre and movement – lent itself to the use of cavalry which, combined with convincing victories over the Turks, contrasted starkly with the mud, drudge and blood of the Western Front. Following the fall of Jerusalem, Allenby humbly entered the Holy City ‘on foot and without pomp’. The occasion was filmed by the official British cinematographer Harold Jeapes and the Australian Frank Hurley. Their newsreel (made into a short film) was shown around the world: it ‘roused genuine enthusiasm’.

The journalist Lowell Thomas, in search of a picturesque war to boost American commitment to the conflict, arrived in Palestine in February 1918 (briefly meeting a young liaison officer: T. E. Lawrence). The material Thomas gathered was turned into a hugely successful show: With Allenby in Palestine (Lawrence was initially cast in a supporting role). Thomas’ travelogue toured the world; it was estimated that some four million people saw the show. The public perception of Allenby the Great Commander was far removed from the myth of the First World War ‘donkey general’ leading ‘lions’ to their slaughter. The laudation of Allenby has continued into modern times. In December 2017 Jerusalem welcomed his descendants to the centenary celebration of a ‘legendary moment’: the city’s liberation from Ottoman rule by Allenby’s forces.

General Wavell’s biography of Allenby – published in September 1940 – perpetuated the image of ‘popular memory’. Its title left the reader in no doubt as to the author’s stance on his subject: Allenby: A Study in Greatness. Wavell had served under Allenby during the Palestine Campaign. He was both a good friend and great admirer. His conventional, ‘middlebrow’, biography describes the (supposed) inevitability of Allenby’s rise to greatness. Published at an extremely fraught time for the British Empire, Wavell viewed Allenby as a source of moral succour and inspiration to a nation at war. Wavell, however, had set out to produce a biography using an historical method. He sought a wide range of opinions from those who knew and had served with Allenby, and garnered peer reviews of his manuscript. Opinions of Allenby varied widely, ranging from outright condemnation to admiration. Forging these opinions into a flowing narrative was to prove problematic, in particular the transformation of ‘the Bull’ of the Western Front, into the Great Commander and tactician of the Palestine Campaign.

Wavell’s solution to this dilemma was to contextualise the Allenby of the Western Front. Thus, the rapid evolution of the fighting into siege warfare did not suit Allenby’s cavalry instincts: there was ‘no opportunity to show his skill in manoeuvre.’ His use of tactics that resulted in heavy losses were the ‘accepted procedure of the British army at the time’. In Palestine, Allenby – freed from the ‘constraints’ of trench warfare – could now utilise his cavalry instincts and wielded his mobile forces to great effect. However, despite wanting to attribute the military victories to Allenby’s leadership Wavell repeatedly concedes the significance of context. The ‘lacklustre’ General Murray had in fact provided the logistical infrastructure that made the campaign possible. Allenby’s officers were indispensable in the planning and execution of the battles.And, Lloyd George kept his promise: Allenby was provided with all the troops and materiel he requested, giving the EEF ‘a significant numerical and material superiority over the Turks’. Indeed, of the Battle of Megiddo Wavell states: it had been ‘practically won before a shot was fired’.

Did Allenby, in Palestine, actually ‘find a success ready made for him’? Adding to this (as yet unanswered) question is that of the worth of the Palestine Campaign: did it assist in winning the war against Germany? For historians there is little ambiguity here. The assessment of Cyril Falls (Official History, 1930) was that it had no direct effect upon the defeat of Germany. Matthew Hughes (1999) concurs: the Palestine campaign was not only peripheral in helping win the war but also ‘a waste of scarce British resources’. Allenby’s enigmatic greatness may have secured some spectacular victories in Palestine but they contributed little to the defeat of Germany and left Britain with a highly controversial legacy.

Julian Daggett graduated with an MA in First World War Studies from the University of Kent in 2019.

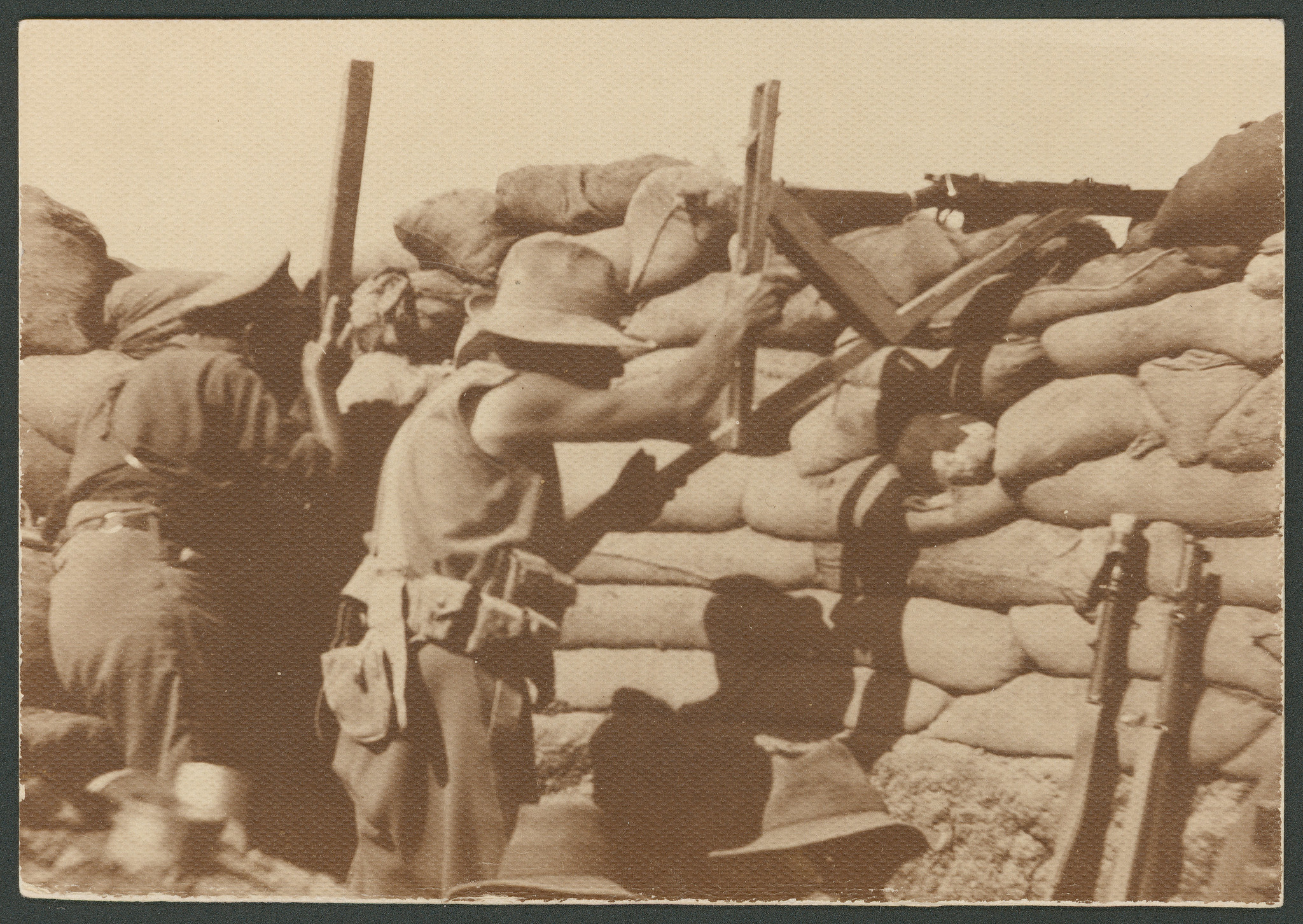

Image Credit: Trench Warfare at Gallipoli CC BY 2.0 by State Library of South Australia/Flickr.