Written by Alisha Reid

If I asked you to picture the 1920s “New Woman”, the image that would come to your mind would most likely be based on what you have seen in films and TV shows – both old and modern – of a sexually and financially liberated woman with her short hair and vampy makeup, her boyish-figure draped in a flapper dress. This caricature is not incorrect but it is exactly that: a caricature. This style of woman is almost synonymous with Weimar German culture following the First World War. It is this “New Woman” that people remember seeing in the numerous films that German studios produced over the period. However, what people often fail to remember are the negative narratives surrounding the “New Woman” in Weimar films and the emphasis placed on abandoning this stereotype.

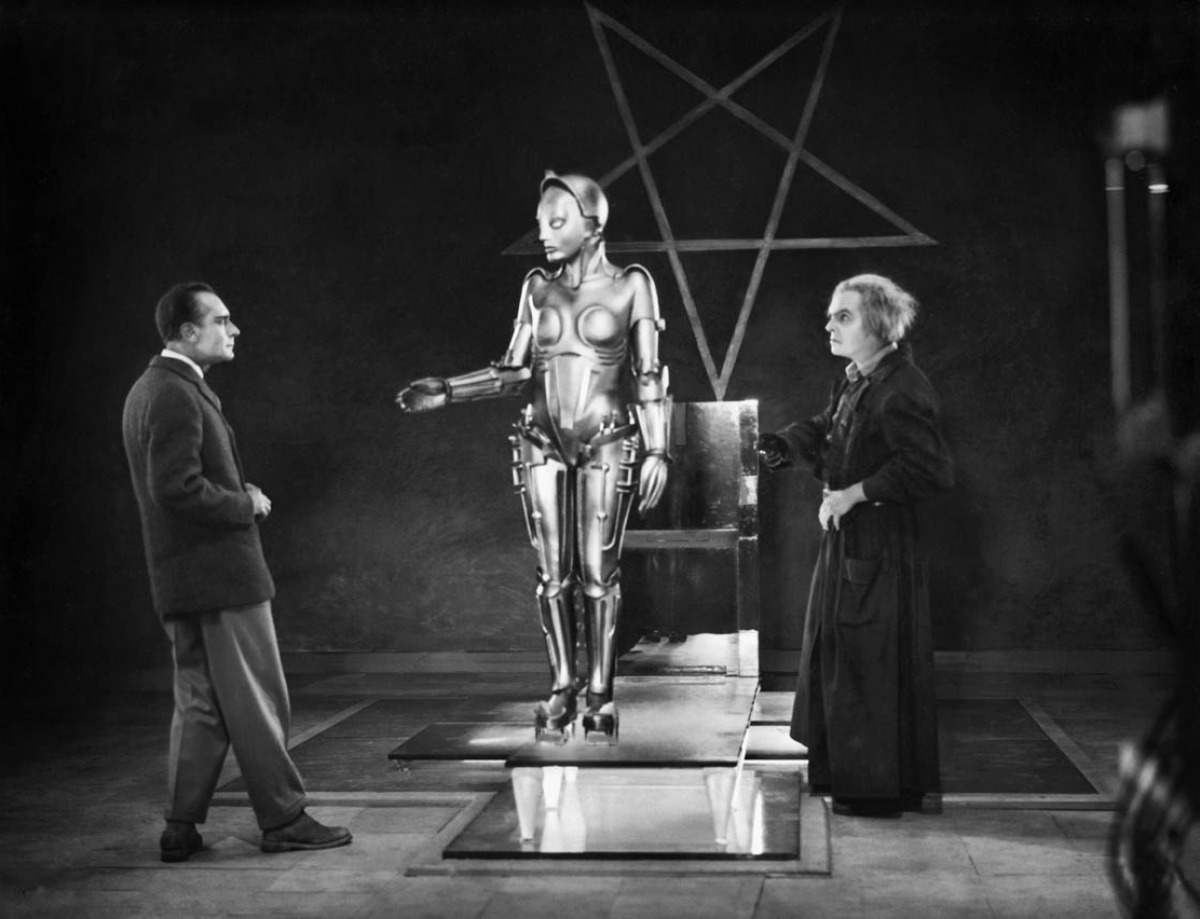

Contrary to what the most popular historic dramas on your screens now would have you believe, the “New Woman” was not a character that the average 1920s or 1930s audience member was supposed to identify with and try to emulate in her everyday life. The “New Woman” and her associated liberal behaviours were supposed to act as a cautionary tale in cinema of the dangers that a woman’s newly declared freedoms could – and in the filmmakers’ eyes, would – result in. As shown with Cecilie in Circe the Enchantress (1924); Greta and Maria in Joyless Street (1925); Maria and Maschinenmensch-Maria in Metropolis (1927); and Else in Asphalt (1929), the “New Woman” behaviours and appearances needed to be cast aside for the characters to succeed. When Cecilie, The Joyless Street’s Maria, Maschinenmensch-Maria, and Else fail to put their “New Woman” behaviours behind them, they are faced with terrible consequences or destruction. Cecilie’s liberated outlook results in her gambling away her fortune and reputation. She faces the consequences to her actions when she is hit by a car whilst saving a child’s life as part of the job she had to get to support herself. However, this maternal change in her priorities is rewarded when her love interest returns to care for her. Greta’s ability to renounce her “New Woman” ways and sexual prowess is rewarded when she marries a wealthy man able to support her – her counterpart Maria, however, fails to do this and is punished with a life of prostitution. Maschinenmensch-Maria’s wicked ways and vampy appearance are ended when she is defeated by the revolutionary crowd and the traditionally maternal and demure Maria is rewarded for saving the city’s children. Else’s frivolity, thievery and wickedness are ended when she faces the consequences of her actions and confesses to the murder of her ex-boyfriend to save her new love: Police Constable Holk. Else appears at the station to confess her crimes in a conservative dress and is freed from the vampy make up she wore before – an appearance fitting for a woman finally taking accountability for her actions. The true message to the audience in these films is not that the “New Woman” was a role model for ideal behaviour, it was that if women wanted to achieve the 1920s fairy-tale ending (i.e., to get married and have children) they needed to renounce their “liberated” ways and accept a more traditional outlook and appearance – none of the protagonists in the films were still financially or sexually independent by the films’ conclusions.

Nazi Germany is not a regime associated with having a liberal outlook on women and their role in society; most people belief that Nazism aimed to relegate women back to the fringes of society. However, the idea of the “New Woman” was not limited to the “Roaring Twenties” period. Each new era in history included some form of change in attitudes towards a woman’s accepted role and appearance. The different representations of women aligned with the different social, political and cultural elements each new regime prioritised. Therefore, the idea that the “New Woman” vanished with the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the establishment of the Third Reich is only partially correct. While the Weimar “New Woman” with her vampy makeup and androgynous appearance stopped being widely displayed, the Nazi regime promoted their often-overlooked version of the “New Woman”. The Nazi “New Woman” was more traditional in the sense that her place was shown as being a wife and mother but atypical in how these roles were respected as a vital part of Nazi society. Instead of relegating women to the domestic sphere, as in the Weimar-era films, women in Nazi Germany were shown as holding a vital place in society through their contributions to their country.

The crux of the ideal Nazi “New Woman” was her endless selflessness and desire to serve her family and community no matter what the personal cost. This nuance in the ideal Nazi woman is easy to overlook when only studying more traditional types of propaganda. However, in Nazi films, this trait is impossible to ignore. Both Rosl in A Mother’s Love (1939) and Elske in The Journey to Tilsit (1939) were shown sacrificing their happiness and even lives for the benefit of their family and community. Rosl donates her eyes to her blind son so he may see again and Elske is prepared to let her husband murder her for the sake of his happiness and the family dynamic. These completely selfless acts highlight the emphasis placed on women to put their family and community first.

This message of selflessness was emphasised even more after the start of the Second World War. Some of the women in the most successful film releases of the Nazi period, Johanna in Joan of Arc (1935), Marie-Luise in Women Are Better Diplomats (1941), and Hanna in The Great Love (1942), are all shown sacrificing their desire for a family and husband for the sake of their community and country – a slight change to coincide with the changing demands of a country at war. Johanna cries over her nationalistic mission stopping her from having a family while Hanna is similarly upset to postpone her wedding to Oberleutnant Paul so he can fulfil his duty as a fighter pilot. These women fit the Nazi’s “New Woman” mould due to their willingness to sacrifice their desires for the benefit of their country – even if it interferes with their traditionally accepted role of a homemaker. This is a narrative which appears incompatible with what we commonly understand of the Nazi Party and its emphasis on a woman’s domestic duty. However, this simply further demonstrates the extent to which the Nazi “New Woman” promoted the idea of selfless service to her country over her desires.

Analyses of women in visual culture reveal both the obvious and hidden messages both regimes wanted to advocate as “ideal” in their society – messages that can be missed when excluding visual culture and women from historical research. Both the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany overwhelmingly used visual culture to promote their beliefs behind the guise of innocent entertainment. The different cinematic fates of the female characters are carefully linked with their promotion of what each regime considered “desirable” or “undesirable” characteristics. Despite the presence of the Weimar “New Woman” in visual culture, women in films were rewarded for rejecting, rather than embracing, the emancipated characteristics that have become so linked to the decade when we think about it now. Likewise, it is often difficult from our perspective in the twenty-first century to appreciate how revolutionary Nazism was to link a woman’s “role” to proactively helping achieve broader ideological aims and not confining women to simply a wife and mother in their films. It appears that, in popular memory, we have almost confused what each regime’s “New Women” really represented: what we label the “liberal” Weimar “New Woman” is not so liberal, and the “traditional” Nazi “New Woman” is not so traditional. These nuanced and subliminal messages in visual culture are oftentimes missed when focusing on the more traditional political, economic, and androcentric histories of Germany throughout these periods. When women in visual culture are analysed, the deeper meaning behind seemingly innocent content becomes apparent and reveals the attempts to subconsciously influence the German public’s opinion of what the “ideal” woman was. As Joseph Goebbels himself emphasised on many occasions: the best propaganda was the type that the audience did not even know they were consuming.

Alisha Reid graduated with a BA in History in 2022. This article is extracted from her First-class undergraduate dissertation.

Image Credit: A still image from Metropolis (1927). License: CC BY-SA 4.0