Written by Mark Connelly

In August 1942 the New Statesman and Nation published Henry Reed’s poem, ‘Naming of Parts,’ which has become one his most famous works. Its focus is a sergeant instructing the men in the handling of their rifle. The instructor luxuriates in the technical language of the weapon. We are told of the lower sling swivel, the piling swivel, the safety catch (and how quickly it can be released with a simple flick of the thumb), the bolt, the breach, the cocking-piece, the point of balance. The rifle is a welter of technical terms and understanding those technical terms means mastering a mystery, it means initiation into a distinct community; it means power.

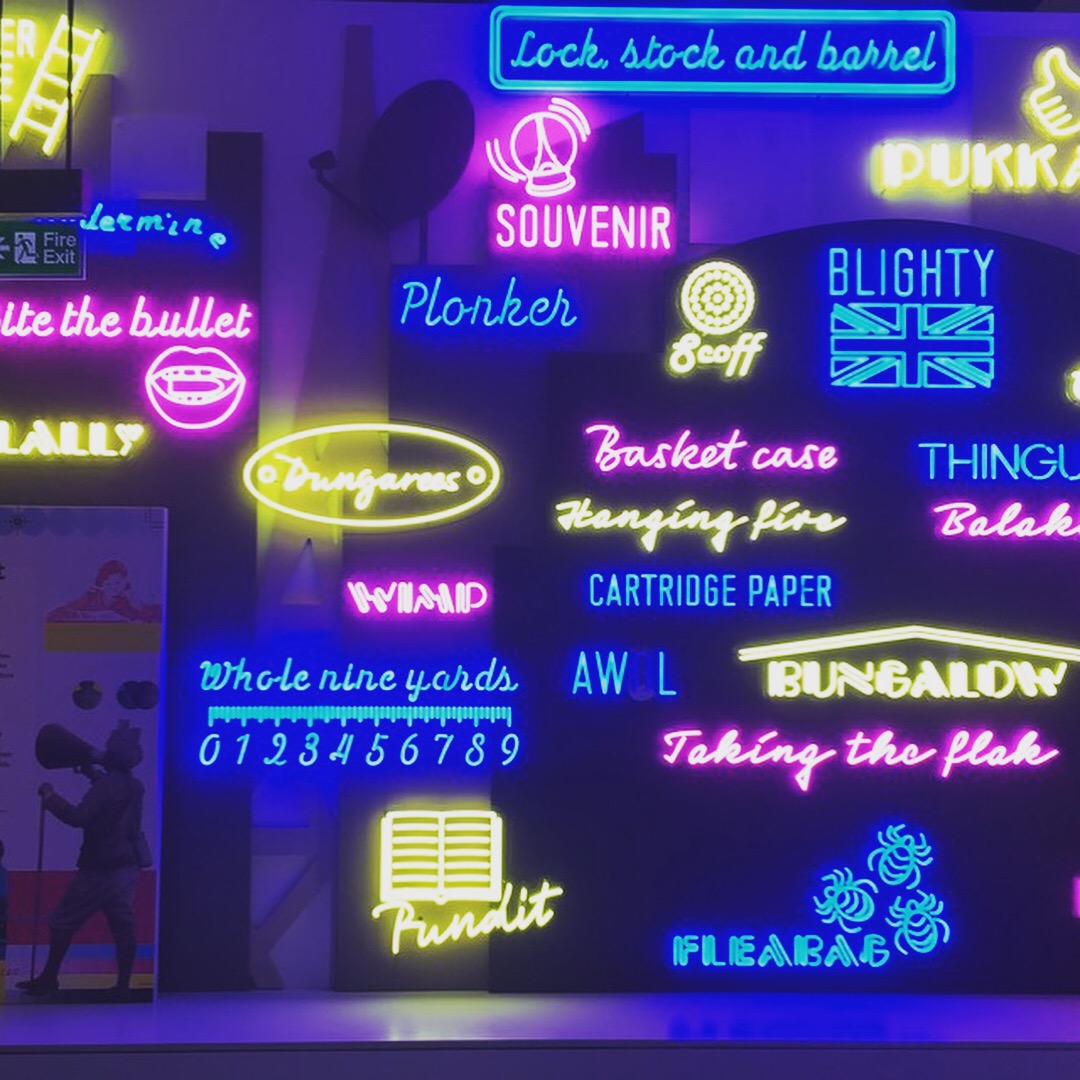

Informed as they are by the work of researchers and theorists in a range of disciplines, historians have long been fascinated by language and words. The role of language and words in concepts of community, of defining who’s in and who’s out, how and what to think and say, who’s allowed to say what, where and when. Words express knowledge and knowledge can lead to command, control, influence, power, and that shapes our record of the past and our understandings of what happened and why and how it happened. Military History is fascinating because anyone who studies it is drawn into a host of language types, words and terms. If I might be allowed to say it, studying Military History is a minefield of language, and it comes in two forms. First, there is the deluge of technical language and acronyms for ranks, orders and kit. Second, there is the strange slang of the services. Combined they make up a communication system as complex, and at times almost as majestical, as the Latin Mass. And, of course, like the Latin Mass, so much of it was designed to be intoned, chanted almost, with responses between leaders and led. The language was about creating a sealed community based on the seemingly contradictory forces of rank and hierarchy on the one side and comradeship and togetherness on the other. In this manner, language was ritual and an act in its own right.

There is a real glory in the sheer profusion of military language: its depth and breadth is remarkable. I particularly enjoy acronyms. SMLE or Short Magazine Lee Enfield is a favourite partly because even when stated in full, it still means nothing to the outsider! Only once the magical missing extra term of rifle is added does someone stand a chance of interpreting it. Even then, they might ask themselves what a magazine has got to do with a rifle, and what’s a groove in metal got to do with anything. Am I getting too literal, now? And what about such luxuriant titles as DADOS, DADVS, or DADMS, the acronyms for Deputy Assistant Director Ordnance Services, the Deputy Assistant Director Veterinary Services and the Deputy Assistant Director Medical Services? Although the acronyms might sound like universes devised for Doctor Who and the full titles something imagined by Michael Palin for a Monty Python sketch, they are fascinating for revealing the complexity of the army, its bureaucratic nature, its thick wiring diagram, which in turn says something about the scale and intensity of warfare by the twentieth century.

Then there is the wonder of services slang, the everyday language of the forces. During the First World War this language became almost poetic due to its allusive power. Many and complex images were conjured up by a few simple words whether it be ‘canteen medals’, which referred to stains on a uniform, ‘civvy kip’ meaning to sleep in a proper bed or ‘cold meat ticket’ for a soldier’s identity disc. Mixed into this amazing melange were the terms the pre-war army brought from India and imperial service including ‘blighty’ for home, ‘shufti’ for a good look around and ‘cushy’ for something easy or delightful. More ingredients were thrown into the pot through the corruption of the French language such as ‘sans fairy ann’, or it doesn’t matter, which was mash up of cela ne fait rien, and ‘napoo’ for over or finished derived from il n’y en a plus. And then there are the trench names, which are glorious in their inventiveness. The war poet Edmund Blunden celebrated this rich diversity in his poem ‘Trench Nomenclature’ in which he name-checks China Wall, Jacob’s Ladder, Brock’s Benefit and Picturedrome. David Jones went one better and paid homage to every aspect of army language, high and low, in the epic poem he based on his own war experiences, In Parenthesis.

When delving through their sources Military Historians quickly begin their language lessons, and once they get the hang of it, do they ever use it! Stranger still, they seem to expect that everyone will understand it. Cadres, corps (pronounced, of course, ‘core’ and not ‘corpse’), lieutenant (pronounced ‘lefftenant’ and not ‘lootenant’… we’re not Americans), lines of communication, open flank, point of manoeuvre, bridgehead. They are chucked around like spent cartridge cases. (Have I just fallen into my own trap, there?) Military Historians, it begins to seem, use military language to emphasize their community within the wider community of historians.

Learning the language of Military History is a fascinating and intriguing process. It requires close study of a range of materials, it means understanding idiom and tone, it means understanding the culture of an organisation, and it means realising that language is never, ever neutral, which is probably apt when it comes to Military History!

Mark Connelly is head of the School of History at the University of Kent and a specialist in the cultural and military history of modern warfare.

Image Credit: Display at the National Army Museum, 2017 by Megan Kelleher. Licence: Licence: CC BY-SA 4.0