Reviewed by Oliver Parken

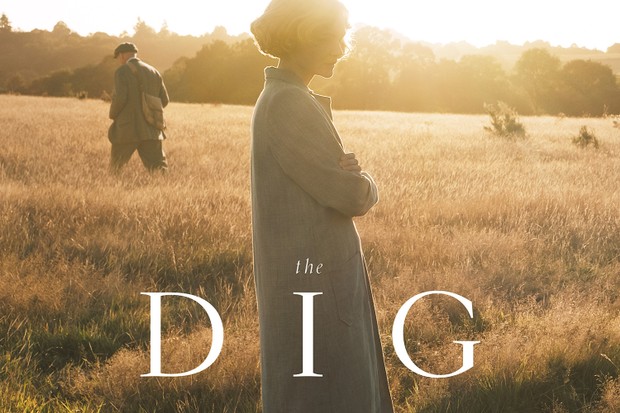

The sleepy Suffolk village of Sutton seems an unlikely backdrop for a major feature film. The Dig, starring Carey Mulligan, Ralph Fiennes and Lily James brings a true story well known to Sutton’s locals to the big screen for the first time. Based on John Preston’s literary adaptation of the same name (2007), The Dig recasts one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the twentieth century on British and European soil––the excavation of a Dark Age ship, packed with a priceless collection of treasure, in the late-1930s.

The film’s main characters, Edith Pretty (Mulligan) and Basil Brown (Fiennes), are seemingly worlds apart. Pretty, a landed widow who lives with her young son Robert, contacts amateur archaeologist Brown about excavating a mysterious set of grassy mounds in a field on her estate in 1938. Intrigued, Brown sets to work on their excavation with a small team of men. Early interactions between the two establish their differences. Pretty comes from an upper-class world of servants and leisure. Brown, by comparison, is a working-class Suffolk man familiar with the geology of the local landscape. Indeed, it is their accents which initially set them apart––Fiennes does a good job of replicating the unique regional Suffolk dialect. But as the drama of the dig unfolds, it becomes clear that Pretty and Brown have a great deal in common. Both suffer social stigma. Pretty’s stigmatisation is gendered (we learn she was forbidden from taking a place at London University by her father). Brown’s is classed (despite being contracted to excavate the mound his expertise is constantly challenged by his social and educational background). Through their determination to unearth the mounds, they come together with likeminded resilience.

The situation changes rapidly when Brown excavates the frame of a ship in one of the mounds. Representatives from the Ipswich Museum, and later British Museum (at the behest of the Ministry of Works) take over the dig and temporarily oust Brown. The significance of the find begins to emerge. Archaeologist Charles Philips of the British Museum (Ken Stott) recognises this, but challenges Brown’s contention that the ship is Anglo-Saxon. Official/local tensions are amplified here, particularly in the frequent references to Philips’ title of Cambridge ‘archaeologist’ compared to Brown the ‘excavator’. Ultimately, Brown’s is proved correct. The ship and its treasure trove dates to the 7th century, revolutionising contemporary understanding of cultural and economic life in the Dark Ages. Although definitive proof remains lacking, the burial site is often attributed to King Raedwald, one of several Anglo-Saxon kings of East Anglia who ruled before ‘England’ came into existence.

The Dig is in many ways a human story. It re-inserts Basil Brown’s unique contribution to the history of Sutton Hoo––a contribution which, for many decades, the British Museum omitted when the artefacts went on display after Pretty gifted them to the nation. It tells the story of Edith Pretty, and her personal battles with illness, grief and single motherhood. It takes liberties when inserting romantic/sexual storylines between several of the younger characters, notably archaeologist Peggy Piggot (Lily James). In uncovering the mounds, these individuals are forced to confront uncomfortable aspects of their own selfhoods. At times this overshadows the main storyline of the excavation and its archaeological significance. The Sutton Hoo helmet, arguably the most iconic discovery made, does not feature on film. In other ways the excavation is secondary to the film’s framing of the coming war in 1939. Throughout, the viewer is aware of building tension between Britain and Germany. Wireless broadcasts and RAF pilots training (one of which meets a watery death after crash-landing in the River Deben) keeps the narrative centred on the context of war. When Pretty journeys to London for urgent medical attention, scenes depict ARP (Air Raid Precaution) Wardens preparing for the ‘knockout’ blow from the air.

But this, in many ways, represents the film’s greatest triumph. By aligning the present context of the late-1930s and images/references to Anglo-Saxon warriors, the past and present collide. The memory of the past––or rather, the unearthing of forgotten local and national memories––signals the timeless nature of war and human struggle. The film’s idyllic Suffolk backdrop, redolent of propaganda images of ‘deep England’ during the war, is disturbed by the impact of the coming war and public/press interest in the dig. Here, the characters are caught in a race against time to unearth the mounds before war sets in. As Basil Brown reveals to Edith Pretty in the early part of the film: ‘it speaks, the past’. Even for modern day audiences, as The Dig’s global success illustrates, it still has the ability to enchant.

A note on Sutton Hoo: the British Museum continues to display the treasures found at Sutton Hoo (including the iconic helmet, armour/weaponry, and a substantial collection of gold and silver). The National Trust runs a dedicated site on Edith Pretty’s former estate near Woodbridge. When re-opened, visitors can explore Tranmer House (the Pretty estate depicted in The Dig) the site of the original burial mounds, and an exhibition centre with replicas of the original discoveries. A recent local initiative in Woodbridge has begun construction of a life size, working replica of the original Sutton Hoo ship.

Oliver Parken is a PhD candidate, and previously Assistant Lecturer, at the University of Kent’s Centre for the History of War, Media and Society. He recently submitted a thesis titled ‘Belief and the People’s War: Heterodoxy in Second World War Britain’, which explores the social experience and cultural shaping of non-standard beliefs as part of the wider dynamics of the ‘People’s War’ at the home and fighting fronts.

Image Credit: Netflix/Radio Times