Written by Peter Keeling.

On 10 May 1888 a notice headed ‘STRICTLY NON-POLITICAL – GREAT BRITAIN’S DANGER’ appeared in The Times. Placed there by a group of naval officers and city businessmen led by Captain Lord Charles Beresford and Admiral Sir Geoffrey Phipps Hornby, it asked ‘Englishmen of all classes and politics’ to consider the truth of the following statements:

The Naval and coast defences are quite inadequate to the absolute requirements of the nation.

The country is to-day unprepared for war, and would risk a serious reverse were such to occur.

Our commerce would be at the mercy of an enemy in the present weak state of the Navy.

These troubling observations were followed with a dire warning: ‘A great war may at any moment burst upon us, in which we may have to fight for our very existence.’ The two basic assumptions underlying the notice – that war was imminent and the country unprepared – formed the bread and butter of discussions relating to national defence in the British Empire during much of the nineteenth century. This pessimistic tendency, and its attendant political vocabulary which stressed the role of social Darwinism in international affairs, only increased as the twentieth century dawned. In the notice itself, we can see the early stirrings of the ‘navalism’ which gain much ground during the following decades, represented by pressure groups such as the Navy League (formed in 1895).

After demanding an inquiry into the state of the Navy, the notice, which was also circulated by hand within the City, announced that a public meeting was to be held early the next week at which ‘several of the leading and most able officers of both the Army and Navy’ were due to speak. Although Britain had a long tradition of servicemen taking part in politics, the sheer number of such men taking part in the 1888 gatherings, along with their implied (at times explicit) criticism of the political system’s ability to maintain the national defences, marked a new departure. At the meeting itself, many took it upon themselves to attack the system of ‘government by party’ which, they claimed, had left the Navy in such a poor condition.

The agitation of 1888 was not a UK-wide concern. Few representatives from outside London attended the subsequent ‘national defence meeting’, which consisted almost exclusively of figures from the military, naval and commercial elites. What was more its language was hyperbolic, even unbelievable – indeed, as research by naval historians John Beeler, Robert Mullins, and Roger Parkinson have shown, there was little real reason for such contemporary concern regarding naval defence. For these historians, the notice of May 1888 was built on little more than a ‘myth of naval weakness’.

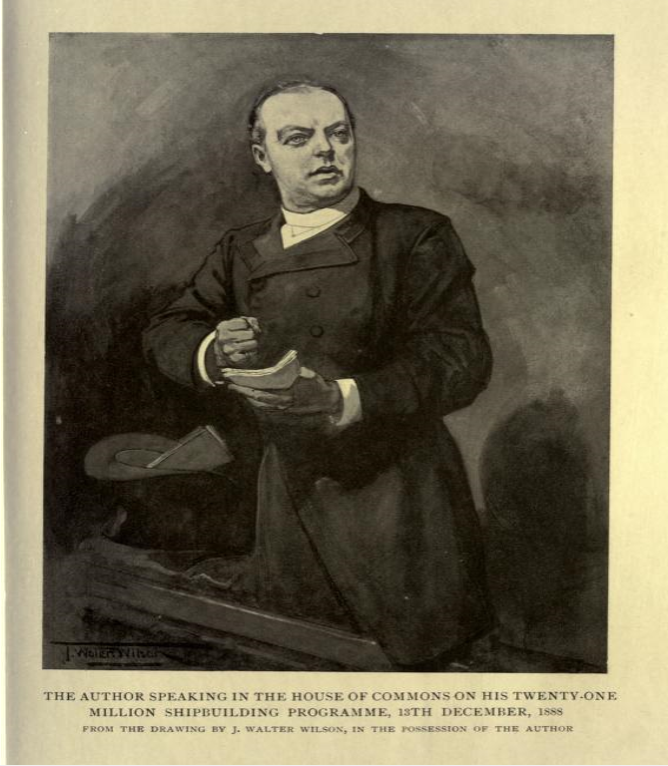

Despite these problems, Beresford, Hornby and their fellow officers successfully positioned themselves above the political scrum. By posing as ‘strictly non-political’, they were perceived as detached patriots acting in the national interest. This was a particularly effective tactic in late nineteenth century Britain, which by the 1880s was beginning to adopt the idolisation of technocrats which became a hallmark of the language of ‘national efficiency’ which so dominated the years 1900-1914. This language’s political potential is shown by the success of the 1888 navalist campaign. By January the following year, the government had drawn up plans for what would become the Naval Defence Act, an enormous increase to the Royal Navy.

Fundamentally, therefore, 1888 shows the power and influence which can be acquired by a propaganda campaign which successfully links patriotism and ‘expertise’, while avoiding the accusation of playing up to party politics. By monopolising the debate and establishing their own narrative of naval weakness, the campaigners of 1888 not only changed the course of British naval policy; they succeeded, as servicemen, in setting the civilian political agenda.

Peter Keeling is a third year PhD student in the School of History at the University of Kent, working on the politics of national defence in Britain during the 1880s.