Written by Emma Hanna.

Pianos seem to be everywhere these days. Walking through St Pancras International station, one of the upright ‘street pianos’ are invariably being put through its paces by a variety of would-be pianists, belting out music of all kinds, from a Beethoven sonata, to Simon and Garfunkel, to the Lion King. Or you get to hear someone reminiscing on their school days with a rendition of Chop Sticks. Even the singer John Legend gave the beleaguered St Pancras piano a turn after a recent journey on Eurostar.

Humans have long been drawn towards music and music-making. The playing of, or listening to, familiar melodies is one humans have been doing for centuries to uplift or console themselves and/or their audience. Bede (673-735 AD) wrote that:

[a]mong all the sciences […] music is the most commendable, pleasing, courtly, mirthful and lovely, It makes men liberal, cheerful, courteous, glad, and amiable – it rouses them in battle – it exhorts them to bear fatigue, and comforts them under labour; it refreshes the mind that is disturbed, chases away headache and sorrow, dispels depraved humours, and cheers the desponding spirit.

British servicemen have a long history of music-making. Soldiers at rest and on the march would have provided their own music way before the formation of the first official Army band, the Band of the Royal Artillery, during the Seven Year’s War in 1762. In 1805, As Lord Nelson led the ships of the line into battle at Trafalgar, the band on the Victory played the National Anthem, Rule Britannia and the patriotic song Britons Strike Home.

In 1914, it has been estimated that there were roughly 3 million pianos in Britain, 1 for every 15 people. At a time before widespread Gramophone ownership, there was a culture of performance where people provided their own amusement and entertainments. Singing and the playing of instruments was appreciated and there was an expectation that those who were capable should entertain. The Pianola, an automatic piano, was popular in Britain but it never attained the commercial success it did in the United States. Several Royal Navy ships had a pianola on board. There certainly was on aboard HMS Lion, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty, as the ship’s magazine Searchlight published a humorous poem ‘Noisy’, alluding to one officer’s ‘boisterous, cyclonic’ nature:

Surely you must regret the pianola,

That placid beast of burden for the feet,

Which you have driven like a Brooklands racer,

Until at last it couldn’t even bleat.

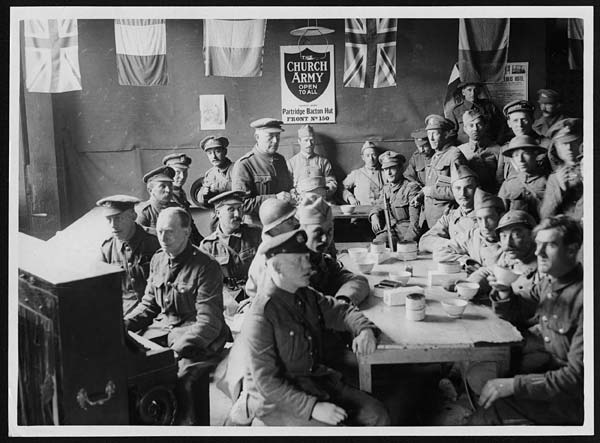

While there were no ‘street pianos’ in stations where servicemen were in transit from one front to another, they could be found in most canteens run by voluntary-aid organizations such as the Salvation Army, the Church Army, and the YMCA. These hut canteens provided a space for servicemen to rest, as well as provide their own music-making with informal recitals and sing-songs around the piano, provided precisely for those purposes. The existence of instruments, particularly a piano, was widely known to help provide a relaxing atmosphere in the rest areas. The composer Percy Scholes, who was head of the YMCA’s Music Department, wrote in 1918 that:

In some huts the piano is hardly ever silent. I remember a Rest Camp in France where it was going from six in the morning till half-past nine at night, unless it might be at meal times; and even then it was not silent long, for some boy would hurry over the meal so as to be first back and get the piano whilst it was free. There were all sorts of players – boys who could merely pick out the notes of the airs of a song-book, extemporizing a left-hand part that did not fit, boys with wonderful natural “ear”, who without having had a lesson in their lives or knowing the name of a note could rattle out rag-time by the hour, and boys who played Beethoven and Chopin in a way which must have made our poor little French piano feel ashamed that it could not do these great composers greater justice. The piano [has] done great service to morale in this war.

One young soldier wrote to his parents that ‘[p]hysical danger is but one part of the trial of war. Quite as bad, to many a man, is the boredom of the Base’:

The weather is awful, and in this camp we walk in mud up to our knees. There is no Y.M. hut here, and nowhere to go and nothing to do. Yesterday I felt in despair, and the others were just as bad. Then I caught sight of a box lying on the ground in the middle of the camp, and some impulse made me jump on it and begin singing, ‘There’s a land, a dear land.’ Everyone gathered round and cheered at the end. After that we all felt better.

The YMCA and Salvation Army each produced their own song books for pianos. These provide fascinating insights into the patriotic and religious musical pieces these organisations suggested were played in their establishments. However, the copies I have seen look remarkably pristine considering they were kept in huts on the fighting fronts for several years. More visibly well-thumbed are the copies of scores used by performers of various concert parties. For example, ‘The Balloonatics’ of the Royal Flying Corps, whose sheet music features the annotation ‘France, 1917’ and is preserved at the RAF Museum Archives in Hendon.

The morale-boosting applications of music in all its forms is integral to the history of 1914-18. It is important for historians to recognise the significance and usefulness of music, to appreciate that far from being ephemeral, the emotional potency of sound and melody surpasses the capabilities of visual images or written texts. Whether it was a bawdy music hall tune, a Chopin piano piece, or a ‘customized’ hymn on the march, soldiers, sailors and airmen routinely made their own music for a wide range of purposes. That servicemen continued to provide their own music, not just as passive receivers of musical entertainments but as primary music-makers, tells us a great deal about the morale and motivations of British soldiers, sailors and airmen 1914-18.

Emma Hanna is a Senior Research Fellow in the School of History at the University of Kent and the author of The Great War on the Small Screen (Edinburgh University Press, 2009). Image Credit: No Known Restrictions, National Library of Scotland/Flickr