Written by Mark Connelly.

Silence is absolutely crucial to our remembrance of the Great War. The thousands of sepia images we have of men queuing up to enlist, marching away to war, slogging through mud encumbered with kit, of women and children reading casualties lists pasted to billboards are curiously hypnotic due to their arresting power framed by, and etched into, the sepulchre silence of the tomb. As we know, everyone in the Great War is dead. In fact, the way we perceive it, they were preordained-doomed-dead in 1914 long before the first shots of the armies had been fired. Never such innocence again is synonymous with the crushing weight of silence; the silence of Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday; the supposed silence of all memory – ‘dad never spoke about the war’ or ‘mum never spoke about dad or how he died’. ‘There we stand, alone in the world, mute before the meaning of the events that befell our generation’, as R.H. Mottram wrote in his article, ‘In Those Two Minutes’.

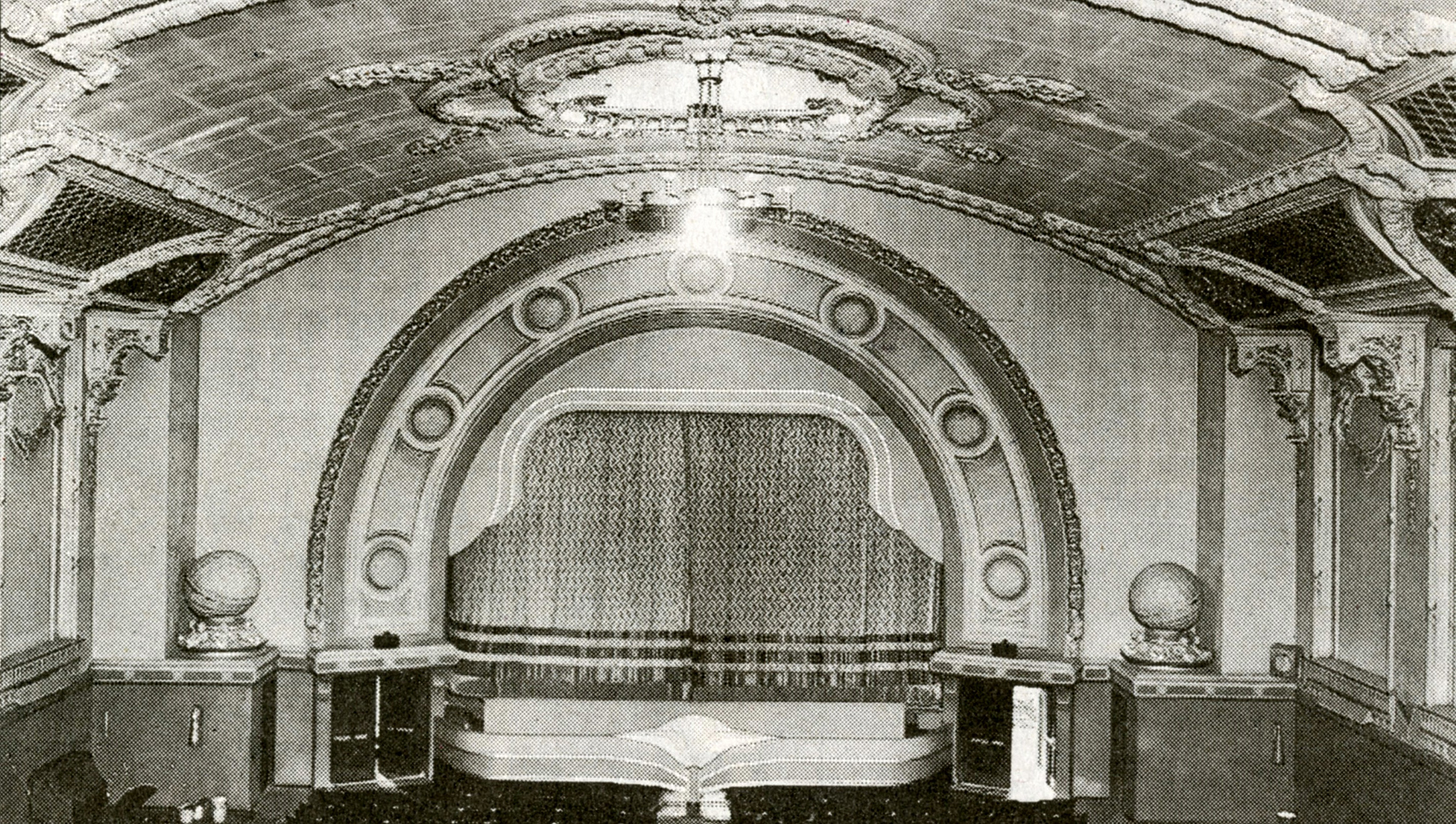

The new toy of twentieth-century communication, the cinematograph camera, played a huge role in recording the stuff of history and translating it into memory. Hundreds of thousands of feet of film were shot during the war capturing activities at the front, immediately behind it, and on the home fronts. In the years after the war, it also captured the creation of remembrance rituals as it recorded war memorial unveilings and the standing-still-silence of Armistice Day itself. These early films are, of course, almost universally known as ‘silent cinema’, and yet this is a misnomer, for silent films were almost never, ever silent. At the very least there would be a piano accompaniment; in medium-sized cinemas small bands were employed, and the largest – so-called ‘super cinemas’ – something akin to a full orchestra. Many cinemas also employed specialist teams to create appropriate sound effects enhancing massively the experience of cinema-goers. Also, and very unlike sound films, the reliance on intertitles meant there was not the same expectation on audiences to sit in silence. With no dialogue to keep track off aurally, audiences were free to shout out, clap, sing and weep. Cinema must have been far more like the music hall, pantomime or Victorian melodrama with their sense of reciprocity between stage and audience.

All of this has significant implications for the way people digested war films in the 1920s. In the British Empire, the leading exponent of war film production was the British Instructional Films company. Dedicated to producing accurate reconstructions of Great War battles, it made a series of increasingly-lavish interpretations with the full co-operation of the War Office and Admiralty. Starting with relatively modest productions in 1921 with The Battle of Jutland, followed by a film about Allenby’s victories in Palestine, Armageddon, in 1923, buoyed by their huge success, the company went on to produce far grander scale efforts. In 1924 Zeebrugge was released, neatly coinciding with its dramatic tableau vivant interpretation at the Wembley Empire Exhibition; 1925 saw the biggest box-office hit of its output, Ypres. A year later Mons was released to equally appreciative audiences, and a year after that its last venture before the introduction of sound film was the cinematic masterpiece, The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands.

In all of these films the sonic was absolutely crucial. For The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands, the New Gallery Cinema in Lower Regent Street special effects team had shovels and coal to replicate the stoking of the boilers, indoor fireworks for the explosives, and heavy metal chains to replicate the sound of cables and anchors. Police were called to a south London cinema at a screening of Mons as a result of its team releasing thousands of blank rounds to replicate the sound of battle. As noted, music was crucial for all films, but in terms of British Instructional Films’ output, Ypres leant itself more fully to an emotive accompaniment. As might be expected, the wartime songs were played throughout, which had a tremendous effect on audiences. In Adelaide people joined in and sang along with the orchestra, as they did in Toronto. G.A. Atkinson, reporting on the premiere for the Daily Express, saw the séance-like potential of the songs to create a communion between the audience, the screen and the dead, stating that the music would fill the Marble Arch Pavilion with ghosts. Sure enough, the first public screening witnessed the audience whistling along with ‘Colonel Bogey’, ‘Mademoiselle from Armentières’ and ‘Take Me Back to Dear OId Blighty’ among others. One man ‘was visibly overcome, and he was led away after the performance, crying as if his heart would break’. Many accounts remark on this emotional effect of Ypres, which must at least in part, have been inspired by the music’s ability to break down the barrier between watching and absorbing as an individual and viewing as a group experience. Atkinson witnessed a middle-aged man at the trade premiere take out his handkerchief and make ‘suspicious noises in his throat… “I was in that” he whispered’.

Just as Mottram noted about the silence of Armistice Day, when a torrent thoughts might fill a person’s mind, the silence of cinema was actually rather cacophonous. And, in total contradiction to those commentators focused on high culture who claim that there was a silence about the war until the 1920s, silent cinema shows us that the total opposite is, in fact, the case.

Mark Connelly is Professor of Modern British History at the University of Kent and the author of Celluloid War Memorials (Exeter University Press, 2016). Image Credit: CC by Paul Townsend/Flickr