Written by Jerry Palmer

The majority of the nurse memoirs of the Great War, of all the combatant nations, focus overwhelmingly on their daily work; through this accumulation of detail, they demonstrate their dedication to the well-being of the soldiers, while by the same token their personal lives recede into the background. However, although they play down just how difficult nursing was under these circumstances, perhaps especially for the thousands who were volunteers with no previous medical experience, it is not difficult to work out just how draining it must have been. This is one example of a basic feature of memoirs: because they are inherently selective, what they don’t say is often as instructive as their contents.

The German nurses’ writings are significantly different from other nations’, in several respects. Firstly, the chronology: British and French nurses published their memoirs during or immediately after the war, with a few exceptions – including arguably the most famous one, Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, which was delayed by repeated and fundamental re-drafting until 1933. The overwhelming bulk of German nurse memoirs were published after 1933 and I’m sure no one needs to be reminded of what happened in Germany that year. Secondly, the two generations of German memoirs (during the war/post-1933) are fundamentally different, both in their content and the public response to them.

These features of German nurse memoirs cannot be a coincidence. There must be something about the Nazi regime that empowered these women to belatedly publish memoirs, most of which had been written 15 to 20 years earlier.

The wartime-published texts are very low on the detail of nursing. They often read like travel diaries, with descriptions of the interesting foreign places they have passed through or visited. They are also very optimistic and reassuring – the arrangements for the care of the wounded are well-organised, they are all in good spirits, they can’t wait to get back to the front, their wounds are cured, and if they die, it is with dignity and surrounded by tender care. These texts were largely ignored by the reading public. The post-1933 memoirs are very different: they are brutally frank about what conditions were like and how hard nursing was, even if the women still maintain composure and dedication; they also make it obvious that medical arrangements outside the homeland, especially on the Eastern and Southern fronts, were far from satisfactory. They received significantly more attention than the first generation and were uniformly praised for demonstrating dedication, bravery and commitment to the soldiers. The difference between these two groups of texts suggests a significant silence in the first generation, as later medical history shows which version is closer to the truth.

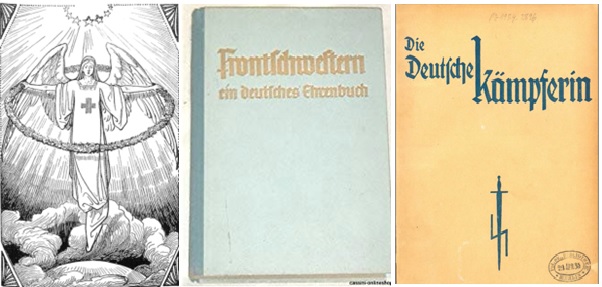

Implicit – and sometimes explicit – in the second-generation memoirs is the claim that they were sharing the soldiers’ lot in life, that they were Kamerad Schwester (‘comrade nurse’ – Kamerad was the term of address adopted by frontline German soldiers for each other) or that they were Frontschwestern (‘frontline nurses’ – frontline service was a badge of honour in post-war Germany). Both of these terms were picked up and used in news reporting of nurses in World War Two, although not widely.

Two elements of the Nazi polity are relevant to the sudden burst of extremely frank portrayals of military nursing life. Firstly, the Nazis weaponised the memorialisation of the Great War, and in particular instituted an Honour Cross, to be given to frontline combatants and to nurses who had served there. Secondly, there was a substantial debate after 1933 about the role of women in the new German social order, one side of which was feminist, as it was explicitly based in the claim of gender equality. The debate is visible in various publications, perhaps most dramatically in the journal Die Deutsche Kämpferin. This version of feminism is distinctively fascist in its orientation, explicitly excluding all notions of universal human rights and basing the claim to gender equality on specific features of Germanic cultural tradition: “a folk-community of Germanic blood cannot in the long run be unilaterally led through male dominance” (Deutsche Kämpferin, 2 May 1933). In this debate, women’s Great War memoirs often figure prominently. The journal, and most of the debate, was closed down in 1937.

This mixture of memorialisation and fascist feminism is a possible explanation of the sudden burst of nurse publications. This is an inference, as there is little direct textual reference to the new context in the nurse writings themselves; one of the few is the editor’s preface to the compilation of nurse writings published in 1936 under the title Frontschwestern: Ein Deutsches Ehrenbuch (Frontline Nurses: A German Book of Honour): “Today we are enjoying the inner healing of Germany, that once again stands proud and tall. So it is that the time of this book has come.” My argument is inferential but I repeat: coincidence is vanishingly unlikely, and these features of Nazi culture are both well-attested and relevant.

However, there is a further element of the Nazi regime in the 1930s which casts a different light on the nurses’ publications. This is the Nazi health system. The Nazis declared that the purpose of their public health system was the development of the folk community, not the welfare of the individual. They were explicit that care directed at the individual was to be proportionate to their worth for the community, as part of German racial heritage: those whose lives made no contribution to, or were detrimental to the racial heritage of the folk community did not deserve care; on the contrary, those who were seen as positively detrimental to it were selected for mass murder – the so-called ‘euthanasia’ programme for ‘less worthwhile’ (minderwertig) lives. On the positive side, the public health care system aimed at interventions to help the growth of a healthy (Germanic) population: the provision of district nurses in every district, help to young mothers, nutritional advice, even an anti-smoking campaign, etc. In addition, since the Nazis had from the outset intended to wage aggressive war, they needed an expanded military medical service. For all these purposes they needed a well-trained and ideologically motivated nursing work force – and they didn’t have it when they came to power. Firstly, there weren’t enough nurses – they estimated the shortfall at around 45%. Secondly, the nursing workforce consisted of organisations with their own traditions of training and care, which did not necessarily coincide with Nazi priorities, especially in the case of the confessional sisterhoods, both Protestant and Catholic.

The Nazis set about creating a nursing workforce adapted to their policies in two ways: firstly, by bringing all the nursing organisations under a single central umbrella organisation; and secondly through expanded recruitment, which involved making it easier to become a nurse – a shorter training period and increased reward. Neither fully succeeded: they never reached the numbers they desired, and nurses enrolled in non-Nazi organisations continued to massively outnumber the Nazi ones by a margin of 70/30.

Despite the shortfall, the Nazis only made marginal use of the nurse memoirs as a recruitment tool – extracts from the memoirs appeared in a compilation to be used in schools, some of the nurses were invited to speak to youth groups, and some of the talks were broadcast. But the evidence is thin on the ground and suggests anything but a systematic use of what first sight suggests was a potentially precious resource – the experiences of committed, able, patriotic women who were competent communicators. Why? I can only speculate, but I have two tentative answers. Firstly, Nazi organisation was less centralized and efficient than is often supposed, and initiatives such as using the nurses were likely to be local and haphazard rather than policy-driven. Secondly, possibly the Nazis didn’t really trust them enough, because their experience was outside the Nazi framework. Their patriotism, despite editorial proclamations about the rebirth of Germany, was not specifically loyalty to the Nazis, it was old-fashioned loyalty to the nation rather than adherence to the Nazi version of it; indeed, since the essence of Great War memoirs was the authentic account of the actual experience, it could not be explicitly Nazi. Whatever the reason, this suggests that the nurse memoirs had a limited compatibility with Nazi values, although this is never said anywhere, to my knowledge.

Jerry Palmer is a former professor of Communications at London Metropolitan University and visiting professor in Sociology at City University, London. His latest book is Nurse Memoirs of the Great War: Britain, France and Germany (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).