Written by Andrew Whittaker

Many of the narratives surrounding British First World War experiences and legacies of service in the armed forces are derived from one of two contrasting class-based perspectives—the social élite or the working classes. The former made up an extremely small proportion of the pre-war male population, the latter a large majority. The experiences and legacies of the lower middle class (who, according to the social stratifications of the time, were situated in between) have been largely overlooked. These were the white-collar salaried employees and the shopkeepers and other small businessmen who comprised a significant one in five or so of the pre-war male population. A longitudinal study from birth to death of the 1350 largely lower middle class men eligible for service in the war who had attended Colfe’s Grammar School, Lewisham, reveals some alternative narratives.

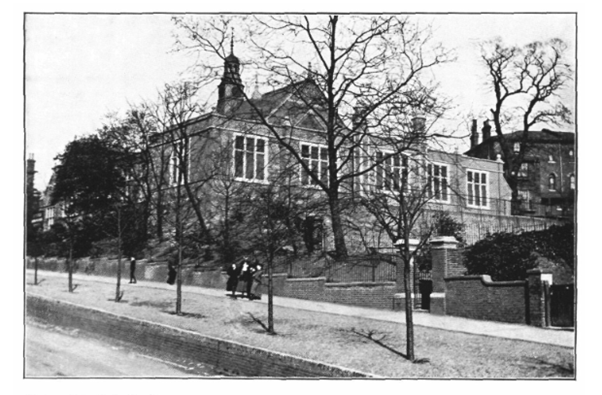

Under a bespoke statutory governance scheme negotiated in the late 1880s, Colfe’s offered a broad modern secondary education including humanities, STEM subjects and modern languages whilst retaining a residual right to teach classics and to teach to age 18 (which preserved the ability to prepare pupils for university). This education was provided in newly erected facilities. Greater provision of public funding for academically able boys from local authority-run elementary schools as the 1900s progressed also resulted in a Colfe’s education being available to a far broader range of backgrounds than previously. This, in turn, would lead to a significant degree of inter-generational social mobility amongst the cohort.

In terms of the war experience, the cohort exhibits larger and earlier (and, therefore, more voluntary) levels of participation than nationally. It also exhibits higher than average fatality rates than countrywide although lower than those claimed for some élite educational institutions. Statistical analysis establishes a correlation between socio-geographic background and entry into service. However, the prospects of death (and disability) seem to be predominantly associated with the nature of service rather than background. The potential subtleties of a hierarchical structure of cause and effect are blurred in much of the existing literature. There are also some more specific departures from generally accepted norms. One of the most striking is that, contrary to accepted thinking, officer status (and especially service as a second lieutenant) was not associated with any enhanced risk of death.

So far as the legacy of this experience is concerned, it has been found survivors had much the same life outcomes as non-servers. This suggests the impact of the war on those outcomes was neutral. There is no evidence of widespread dislocation or disorientation amongst survivors, who generally underwent no dramatic changes in lifestyle, life expectancy, social standing or personal relationships. The overall sense is that the vast majority moved on, leaving their military identifies behind with no desire to be defined by their war experience.

High levels of pre-war migration bring an added dimension to this group of men. Around one in six of the cohort emigrated before the war. This compares with a much lower war fatality rate of one in ten. To this extent, it is clear pre-war migration resulted in a far greater domestic population loss than war death. The headline migration levels reflect the national picture but there was greater movement than nationally to destinations other than the Dominions and the USA. The migrant war experience differs from the remainder of the cohort and especially for those who served in the armed forces of their country of destination. The overall legacy does, though, remain one of continuity with most survivors picking up their pre-war migrant lives where they left off. Levels of first-time post-war migration were reduced. Again, this is in line with national patterns. However, in contrast to those patterns, the Colfe’s cohort shows a distinct shift in movement to the colonies and quasi-colonial areas. It is arguable that, at least in part, the departures from national patterns both pre-and post-war are a product of these men’s educational background, strengthened post-war with an enhanced sense of national identity generated by the war experience.

Dr Andrew Whittaker is a cultural and social historian of early twentieth century London with a particular interest in the First World War, education, migration and social class. He is an Associate Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and currently Honorary Graduate Research School Fellow at Goldsmiths, University of London, working on developing his first monograph. This article is based on a paper delivered at the War, Society and Culture seminar at the IHR.

Image Credit: The New School Buildings from Leland Duncan, History of Colfe’s Grammar School (The Worshipful Company of Leathersellers, 1910), opp. p. 179 (att. to R. L. Hewitt and taken at some point after 1897).