Written by Gary Willis

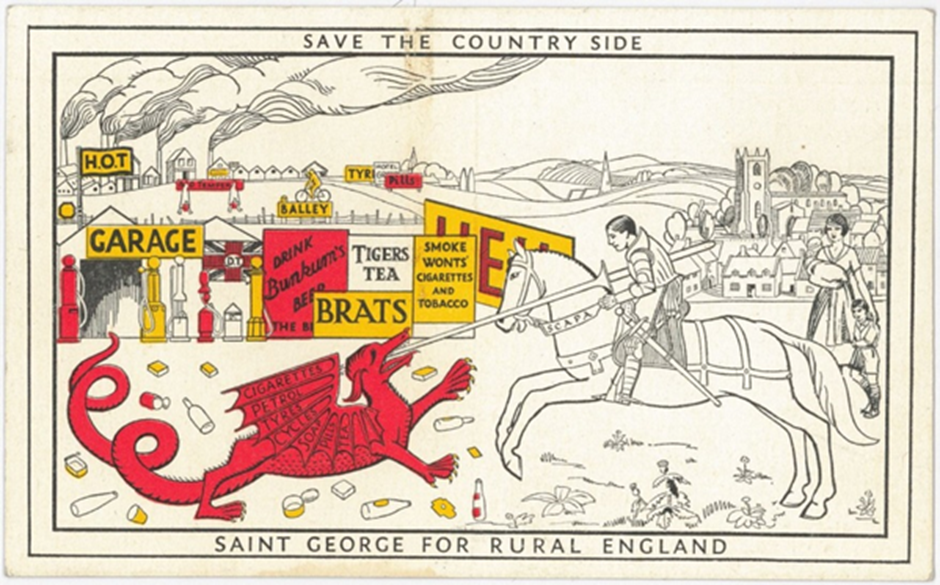

In 1928 the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) produced a ‘Saint George for Rural England’ campaigning postcard. It depicted haphazardly located industry, petrol stations, road-side advertising and litter being slayed by CPRE in the image of St George. Soon, however, there was a growing threat from an entirely different direction – preparations for war.

CPRE’s Second World War began in October 1935, when its Executive Committee considered opposing Air Ministry plans to build an aerodrome at the village of Woodsford in Dorset. The military’s demands for land would feature in every Executive Committee meeting of CPRE until well into the post-war period. Prompted by the loss in 1937 of valuable agricultural land in Wiltshire to the government’s military demands, CPRE lobbied Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain for the establishment of a formal consultation process with government departments regarding the location of military-industrial sites, airfields and other military needs requiring land. CPRE was hopeful of a positive response, as Chamberlain was an avid bird watcher and otherwise generally very sympathetic to conservationist causes; he had spoken at CPRE’s inaugural meeting and had allowed No. 10 Downing Street to be used for a CPRE fundraising gala.

Chamberlain tasked his most trusted senior civil servant fixer, Sir Horace Wilson, with the job of bringing together those government departments tasked with prosecuting a future war to explore how such a consultation procedure might work. But there was push-back from some of the ministries. The War Office representative thought it unwise to involve local authorities because of the need for secrecy and ‘the likelihood that consultation would invite opposition’, which would lead to protracted negotiations for land. And the Air Ministry representative quipped that ‘there was always opposition from various interests, but that it was apt to settle down as time went on’. To break the impasse, Wilson asked those assembled whether they would agree it was not feasible for the Prime Minister to address the House of Commons and say that the government departments’ ministers did not find it possible to undertake any prior consultation. This served to concentrate minds, and the assembled agreed to a solution requiring all the assembled departments to appoint liaison officers whose responsibilities it would be to act as contact points with those civil ministries that had an interest, and also CPRE.

Now the organisation would be an acknowledged stakeholder, albeit by no means an equal partner. It was a quite exceptional achievement, given this meant CPRE was to be trusted with highly sensitive documents at a time of growing national emergency. Consultative mechanisms were put in place during the course of 1938. Frustratingly for the historian, CPRE was publicly circumspect about the detail of its work in order to protect its privileged position and reputation as a state confidante. But it is clear from the long archival series of Executive Committee minutes that it was being actively consulted on a large number of Defence Department proposals. In its monthly report of April 1939 CPRE reflected on the previous year: it felt that with one or two exceptions, the acquisition of land for defence and other war-related purposes had proceeded with less friction than in the past. These mechanisms held up for some time into the war, even though the architect of them, Chamberlain, was no longer prime minister by May 1940, and was dead by the end of the year.

Understandably, CPRE had a particular sensitivity towards Defence Department activity around potential national parks. One such proposed incursion by the Ministry of Aircraft Production, to build a seaplane assembly factory on the shores of Lake Windermere in the Lake District, met with concerted but ultimately unsuccessful opposition on the part of CPRE. ‘We are prepared to make a fine fuss, even in our present national emergency’, CPRE’s Honorary Secretary wrote to a political contact, adding with regard to the need to engage in armed conflict in order to preserve the best of England, ‘after all, if we must fight, let us have something left to fight for’.

Inevitably perhaps, CPRE failed to completely block demands for sites when the state was set on a particular location. However, if other potentially less damaging sites could be identified, then the organisation could be successful in redirecting the state’s attention elsewhere. CPRE could also negotiate which pockets of land within a site needed to be used and which could be left alone, and the state could occasionally be persuaded to accept less land at a particular location. Furthermore, CPRE was consulted on the architectural style of some sites and the most appropriate materials to use, so that they might have a chance of blending in with their surroundings.

In 1945, in a letter to The Times, CPRE reflected that as the urgency and volume of the country’s war needs developed, the procedure had tended to fall into abeyance. But as CPRE was keen to state during the war whenever these mechanisms were not always initially adhered to, the undertaking was precise and had never been revoked.

Gary Willis is an environmental historian. Having obtained his doctorate from the University of Bristol in 2023, he is currently working on his first monograph – working title – Fields into Factories: The Military-Industrial Enclosure of Britain’s Countryside in the Second World War, to be published by Bloomsbury Academic in late 2026. The above article is based on a paper delivered at the War, Society and Culture seminar at the IHR.

Image Credit: ‘Saint George for Rural England’, postcard published to accompany the ‘Save the Country Side’ exhibition, 1928; courtesy of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, ©CPRE.