Written by Andrew McCarthy

“‘You’re in a tight corner, Richard Hannay’, I said to myself. I was crouching behind the Chesterfield in the drawing room. Von Schwabing’s men kept up a steady fire. Bullets had shattered the French windows, and the curtains billowed in the breeze. I knew that Sandy and his men were on the other side of the garden wall. If I could cut across the lawn and reach the wall, I might have a chance. I buttoned my Aquascutum, and made sure that my pistol was secure on its lanyard. I stepped through the shattered windows, and took aim at a rifleman kneeling beside a tree. A pistol bullet bored through my hat. I fired. The rifleman slumped to the ground. This was going to be a first-class show.”

The illustrator who drew the picture on the cover of the Penguin edition of John Buchan’s The Complete Richard Hannay wanted to show that Brigadier-General Hannay is a brave, dashing British officer. He has drawn the Brigadier outside the smashed French windows, pistol at the ready. Hannay wears a peaked cap, a Sam Browne belt, and a trench coat, all symbols of the British Army officer during the Great War.

The Great War brought about the circumstances which inspired Thresher and Glenny, a firm of military tailors, to create the trench coat in September 1914. The way that tailors advertised trench coats in wartime still influences the way in which we see and think about the coats today.

Tailors in 1914 did not have the synthetic waterproof fabrics which are available in 2023 to keep out the wind and the rain. They had to rely on natural materials; wool, cotton, leather, fur, duck down, feathers, sheepskin or goatskin. Thomas Burberry, a Basingstoke outfitter, pioneered weatherproof clothes. He wanted a fabric which he could market to the huntin’ shootin’ fishin’ set, who made up a large proportion of his customers. He encouraged cotton-spinners and weavers to experiment, and in 1879 he developed gaberdine, a fabric which was waterproofed before it was woven and tailored. Burberry and his rivals were now able to keep civilians and army officers warm and dry. In the early 1900s Henry Newbolt, poet of Empire, wrote to his wife Emily after a rainstorm, “Thank God for Aquascutum”.

In the 1890s, civilian and military tailors (some were both) advertised widely in newspapers and magazines. There was a long-established practice in the British Army that the Quartermaster supplied ‘other ranks’ with kit, but that officers bought their own. In September 1899, during the South African War, Burberry advertised “Kharki Gabardine” in The Field, and said they would soon open a branch in South Africa. The Field was not printed on sophisticated presses in 1899, and could not reproduce high-quality pictures. The advertisement has a blurred drawing of a man on a horse. He wears a broad-brimmed hat, and wields a lasso. By February 1900, the illustration, still blurred, shows a mounted officer, wearing a forage cap, and a short, lightweight Burberry jacket. Burberry assured readers that they supplied waterproofs to General Buller, General White and Colonel Baden-Powell. The illustrations are straightforward and workmanlike; no-one is posing or striking an attitude.

Before the Great War, Aquascutum, Burberry, Cording’s and other tailors all sold officers’ waterproofs, but most officers called them ‘Burberries’, no matter who made them. The British Expeditionary Force began to land in France on 12 August 1914. On 13 September, the B.E.F. began to entrench on the Aisne. The mobile warfare of the first weeks had ended. The weather was bad. In October, an anonymous officer wrote in The Times that since 25 August he had needed his Burberry because “it rains every day and the roads and fields are a perfect sea of mud”. On 2 December, another officer said that he had been relying on his Burberry and a woollen waistcoat to keep him warm and dry. The B.E.F. was having to adapt to life in the trenches. It was cold and wet: “a nip of brandy when chilled through at night is worth a deal”.

The words ‘trench coat’ first appeared in print in an advertisement in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News on 19 December 1914. Thresher and Glenny stated that it was “designed for the present conditions of warfare; Mud, Trenches and Clay”. Thresher’s placed a similar advertisement in Punch a few days later. They claimed that the coat was “absolutely waterproof” as well as “wind, wet and mud resisting”. It cost six guineas, the equivalent of £643.20 in 2021. If a firm priced a product in guineas, they were telling their customers that it was superior, better than something priced in pounds and shillings. A guinea was one pound and one shilling, £1.05 in decimal currency. The illustrations in the advertisement are workmanlike; two line-drawings of an officer wearing a trench coat. The coat has the features which help us to recognise it as a trench coat. It is double-breasted, has a collar which the officer can turn up and fasten at the neck, shoulder straps, a belt, and straps on the cuffs.

By 1914, many magazines had improved the quality of their printing. The Sphere had been founded in 1900 expressly to provide high-quality illustrated weekly news of the South African War. Weekly news magazines such as The Sphere, The Graphic and the Illustrated London News could print drawings and photographs of a much higher quality than daily papers.

In March 1915, Punch published a cartoon of three officers, drawn by Captain Duncan Campbell. First, the British officer as seen by the military tailor; a fashion-plate with a doll-like face, laden with a Christmas-tree of equipment. Second, as he actually appears on leaving for the front; a smart officer with a walking stick, a Burberry, a pistol in a holster, and a roll of bedding. Third, as he is after three weeks in the trenches; a dishevelled and very muddy officer. He no longer carries a pistol, but has a Lee-Enfield rifle. A woolly hat has replaced his peaked cap, and he has a small bag. His boots are muddy, and the barbed wire has ripped his uniform jacket and Burberry. All the details ring true. I do not know who Captain Campbell was, but I am sure he was in the front line.

The illustrations in the Thresher and Glenny advertisements in 1914 and early 1915 are simple, more like drawings in an Army and Navy Stores catalogue than fashion-plates. By April 1915, Thresher’s were using a more stylish drawing; an officer wearing a trench coat and peaked cap, his left hand cupped around his mouth, halooing a comrade, or shouting orders. There was no consistent house style for Thresher and Glenny advertisements during the war; a twenty-first century advertiser would have brand guidelines to ensure consistency. The post-1915 Thresher advertisements are striking, and show drawings of dashing, trench-coat wearing officers in dramatic poses. In May 1916 a landscape format advertisement in The Tatler shows one officer standing on each side of the frame. The right-hand officer is gazing upwards, pipe in mouth, trench coat buttoned up, defying all that Jerry, and the weather, can throw at him. The left-hand officer also smokes a pipe. His trench coat is unbuttoned, and he is pulling something, probably a map, from his tunic pocket.

Before the Great War, Second Lieutenant Kenneth Bird had been a civil engineer, but he wanted to be an artist. When he was recovering from the wounds he had received at Gallipoli, he started sending drawings to the comic paper Punch. On 9 July 1916, Punch printed, under the name ‘Fougasse’, “War’s Brutalising Influence”, a satire on the way that military tailors had changed their advertisements. The drawing shows two officers. On the left, a neat, unreal-looking officer in a smart uniform, who looks as though he only exists in two dimensions. On the right, a rugged pipe-smoking officer. He wears a trench coat and a soft cap, and stands with one foot on the firestep, map in hand. He looks as though he could strangle six Jerries before breakfast. This was Kenneth Bird’s first published cartoon, and he went on to have a long and distinguished career as a cartoonist.

As the war progressed, many advertisers adapted the style of their illustrations to show off their products in the best light. Some used realistic illustrations, and some did not. In June 1916, Burberry showed a tin-hatted officer in advertisements for the Summer Trench Warm, made from light-weight cloth, but “stout enough to resist the roughest weather and wear”. From August to November 1918, Thresher and Glenny produced a series of stylish advertisements for ‘The Thresher’, as they called their trench coat. They hoped that ‘Thresher’ would replace ‘Burberry’ as a synonym for ‘waterproof.’ All of the advertisements used drawings of officers.

“NEARING ITS FOURTH YEAR” said the advertisements in Land & Water and The Bystander in August, 1918. A trench-coated officer holds a pair of field-glasses in his left hand, and points to the figures ‘1914.’ He wears a soft cap, and appears to be shouting an order.

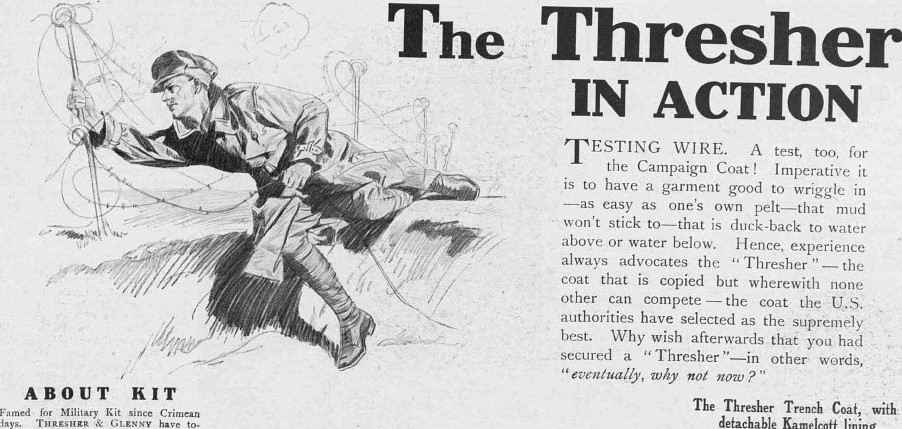

Shortly before the end of the war, in late October 1918, an advertisement in Land & Water shows “THE THRESHER IN ACTION”. A trench-coated officer, in soft cap, stands on the parapet. He is pointing into a trench with his stick. His other hand beckons a comrade. In the background, we see sketchy barbed wire and exploding shells. Why is this officer not wearing a tin hat? By 30 October, in The Bystander, the officer is “TESTING WIRE”, in trench-coat and soft cap, lying astride the parapet as he holds an iron stake with one hand, and a strand of barbed wire in the other. Shells are bursting behind him. On October 31st, in Land & Water, still in the same outfit, he is throwing a Mills bomb. “Over 24,000 officers wear Threshers”. On 14 November, three days after the Armistice, in Land & Water, he crouches on the ground like a sprinter on the blocks, a revolver in his right hand. “THE THRESHER IN ACTION – ON NIGHT PATROL.” A note of reality has crept in. A small box under the picture says:

“Criticism from B.E.F. ‘Send your artist out here – where’s the steel helmet, the box respirator, and all the rest of it?’ Good judge, the critic – but to garble Shakespeare, ‘the coat’s the thing, and in selling ‘Threshers’ tin hats and gas masks hardly matter’. ”

In 1922, William Gerhardie published Futility: A Novel on Russian Themes. It is set during the Russian Civil War, when British forces were helping the White Russians. In one scene, Andrei, a British Army officer, and the narrator, takes General Bologoevski to dinner at the ‘Zolotoy Rog’ restaurant in Vladivostok. The head waiter politely tells the General that, by order of the Commander-in-Chief, Russian officers are not admitted into restaurants. In an undertone, the waiter suggests that the General removes his epaulets:

“‘What? Remove my epaulets! I, a Russian officer? Never!’ he protested.

Whereon a brainwave struck him. ‘I know’, he said, looking round the restaurant. It was nearly empty. And instantly he compromised by putting on his mackintosh. ‘Now,’ said he, ‘in my English Burberry they will take me for an English officer. Ah!’”

The image of the dashing, Trench-coated British officer, ready to take on any task, has become the most important thing, a symbol of Officer-ness. “We’ll do it! What is it?” as Major (later Lieutenant-General) Tom Bridges, of the 4th Dragoon Guards said in August, 1914, in pre-trench coat days. Brigadier-General Hannay would have approved.

“It had started to rain heavily. “Richard Hannay, you’re going to have to run.” I fired my pistol again, and ran. The rain spattered onto my Aquascutum. A bullet pattered into the wall behind me. I was going to make it.”

The John Buchan extracts? I wrote them. It’s more difficult than one would imagine.

Andrew McCarthy wrote The Huns Have Got My Gramophone: Advertisements from the Great War. He directed the film Higher Mathematics Made Fun, a documentary about an eccentric who built his own trebuchet.

Image Credit: From Thresher and Glenny, ‘Trench Coat: The Thresher in Action,’ Land Water November 14th 1918, p. 600. Image Author’s Own.

Educational and entertaining. Thanks to the author

It would seem that Andrew McCarthy has become something of an expert in advertising techniques in WW1 and their reflection of British life in general. This fascinating period, which ironically, ran alongside the living hell of trench warfare was brought about because, he tells us, ‘There was a long-established practice in the British Army that the Quartermaster supplied ‘other ranks’ with kit, but that officers bought their own.’ It followed that the well-off officer class was the perfect target for intensive persuasion to ‘Buy the Best!’ Also, these ads seem to imply, not only would the garments keep you warm and dry, you would (if you survived) cut one heck of a figure of manhood. The birth of highly targetted advertising?