Written by Mario Draper

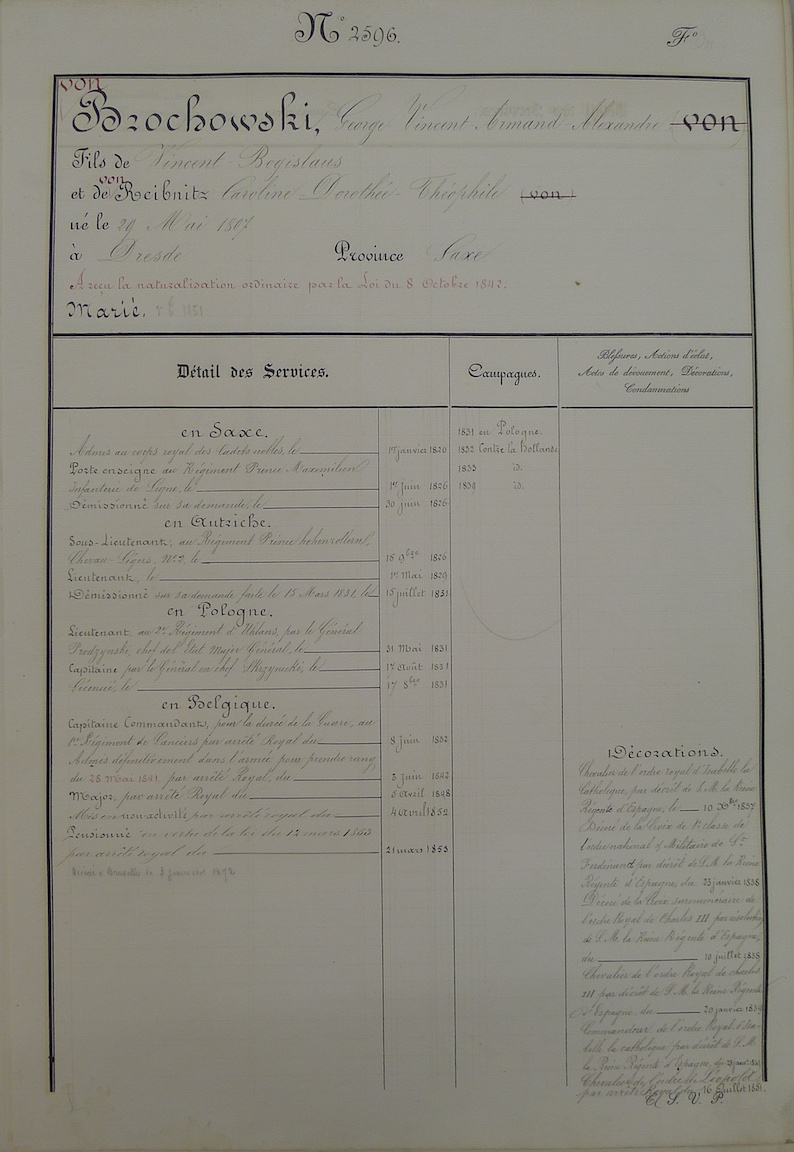

When considering which primary source to select for this blog post, I kept on coming back to the significance of a letter written by a Polish officer Armand von Brochowski to King Leopold I of Belgium on 24 November 1846. In it he explained why he, and dozens of other Polish officers, had made the perilous journey across Europe in the early 1830s to join the Belgian Army.

At the time, Belgium was home to the most liberal constitution in Europe, having gained independence from Dutch rule in the Autumn of 1830. By contrast, the unfortunate Poles were forced into exile following their own failed liberal revolution against Russian oppression during the winter of 1830/31. In Belgium (as well as France, whose own July Monarchy had been installed on a wave liberal idealism that swept Europe in 1830), the Poles found a second home. As von Brochowski outlined, ‘it was changing location without changing flag nor dreams’. For him Brussels and Paris represented proof that liberalism could overcome reaction and offered hope that, one day, it could triumph back in Poland and deliver the Kingdom from Tsarist oppression.

As military careers go, Armand von Brochowski’s was certainly varied. Having been admitted as a cadet in Saxon service aged 12 in January 1820, he was commissioned as an ensign six years later, before transferring to Austrian service as a Second Lieutenant. Here he remained for five years, being promoted to Lieutenant in 1829, before joining the Polish rebels in 1831, rising to Captain. Once in Belgian service (where he retired as a Major in 1853), he obtained a period of leave to serve with the liberal Cristino forces in Spain during the First Carlist War (1833-1840). During his three years away between 1835 and 1838, von Brochowski saw combat as a cavalry officer earning himself recognition for his ‘generous sentiments, which push him towards the defence of liberty’. This episode of his career is interesting for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it shows the degree to which an individual could be motivated by a political cause (in this case liberalism) and hop from army-to-army in order to uphold its principles. This speaks to a much wider phenomenon that historians have identified in this period: the prevalence of a ‘liberal international’. Indeed, foreign fighters (some might call them mercenaries) were a common feature of early-19th Century battlefields either as individuals or as part of auxiliary legions. Among the most famous was Giuseppe Garibaldi, who cut his teeth in the Wars of Latin American Independence (1808-1833) before returning to Europe to help unify Italy. Others, less famous individuals, could speak to even more varied and extraordinary careers.

Secondly, it demonstrates how integrally linked transnational soldiering was to politics and diplomacy. The fact that von Brochowski was afforded leave to serve in a war in which Belgium was (as always) neutral, speaks volumes about the degree to which fledgling international law could be manipulated by states to their own advantage. Indeed, this was not the first time in Belgium’s very short history as an independent state that its government had sanctioned a military intervention in a foreign war. Throughout 1832 and 1833, a Belgian legion supported the liberal forces of Dom Pedro in the War of the Two Brothers (1828-1834) in Portugal. Despite the inherent dangers of contravening neutrality, Belgian officials were prepared to turn a blind eye to the legal loopholes that allowed individuals to serve in the defence of other liberal causes. In much the same way, recruitment for the Union Army some three decades later proceeded relatively unchecked.

Parallels with British diplomacy are manifold. Despite introducing the Foreign Enlistment Act in 1819 to prevent the recruitment of further British subjects into the patriot causes of Latin America tacit support (masked behind a nominal policy of neutrality) resulted in but a lukewarm application of the law on so-called offenders. More overtly, the Act was entirely suspended in 1835 to allow for the British Auxiliary Legion to be raised for service with the liberals during the Carlist War whose ultimate victory was seen to be beneficial to British foreign policy in Europe.

Foreign service, neutrality, politics, and diplomacy cannot be understood in isolation from one another. From a single line in a letter written by a Polish transnational soldier, a whole world of interconnectivity emerges. Not only does von Brochowski’s own remarkable experiences tell their own story, but thousands of others like him link European liberal movements to those in Latin America and beyond. Indeed, if one were so minded to track down the many other transnational soldiers in this period, their stories would take you to North America, Africa and Asia as well. What we’re dealing with here is a transfer of political ideas, professional knowledge, and military cultures – all of which is wrapped up in broader questions of diplomacy, neutrality, and the development of international law.

Dr Mario Draper is Senior Lecturer in Modern British and European Military History at the University of Kent. His book, The Belgian Army and Society from Independence to the Great War (2018) deals with issues of nation-building and neutrality – within which transnational soldiering features and has provided the spark for his latest ongoing research project.

Image Credit: An extract from Von Brochowski’s letter. Image: Author’s Own.