Written by Stefan Goebel

Today it would be scandal, but back then, 35 years ago in February 1988, hardly anyone raised an eyebrow when the Black Form (Dedicated to the Missing Jews) was bulldozed to the ground. To be sure, this black cube built of blocks of aerated concrete was never meant to be a permanent memorial; it had been commissioned as a temporary work of art. The American artist Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) had created it for the second instalment of the international Skulptur Projekte exhibition in my home town Münster in 1987.

I vaguely recall seeing the Black Form in 1987–88, positioned prominently in front of the Baroque palace, home to the University of Münster. But I only started exploring this memorial several years later. In the meantime, there had occurred a seismic shift in the tectonics of Holocaust remembrance: that is, the emergence of the memory boom, centred on the legacy of the Shoah, and fuelled by the end of the Cold War, German reunification and the passing of the generation of witnesses. The early 1990s were a period when many new Holocaust memorials were unveiled. It seemed difficult to fathom that, only a few years earlier, one monument had actually been dismantled.

The history of the Black Form (Dedicated to the Missing Jews) is complicated. Like all contributions to the sculpture exhibition, Sol LeWitt’s was supposed to be a temporary intervention in the urban space for the duration of the show in 1987. The artist, though, was prepared to gift the Black Form to the city or the Land (that owned the ground) for permanent display. Yet many visitors perceived the stark Black Form as a visual provocation, even as a defilement of the Baroque splendour. A local newspaper reported that the Black Form was given a new coat of black paint every 48 hours. Paradoxically, it was only after the exhibition had ended (and after the Black Form had been removed) that a fierce debate about the commemorative dimension of the installation erupted. In the run-up to the fiftieth anniversary of the Kristallnacht pogrom in November 1988, the local party leaders of CDU, SPD and FDP launched a campaign to resurrect the Black Form. They faced widespread opposition, including from their own party colleagues, the university leadership, the district president and, surprisingly, the Green party. In the end, the initiative came to naught, and LeWitt decided to donate his sculpture to the city of Hamburg.

The artist’s original brief had been to produce a work of art, not a memorial. The title of his installation came as a total surprise, even to the exhibition organisers. Such a dedication was completely out of kilter with LeWitt’s minimalism. A premier representative of conceptual and minimalist art, LeWitt’s ‘structures’ (as he called them) have names such as 123454321. This was the first time LeWitt had given one of his abstract works an evocative title. The inspiration came when he first visited Münster, a university town buzzing with student life. Seeing students rushing to lectures and hanging out in cafes prompted the question: what about those medical or law students who were never born because their parents had perished in the Shoah? Unlike most Holocaust memorials, which remind us of those who were murdered, the Black Form is dedicated to the unborn ‘Missing Jews’; it is designed to highlight a gap in the present, not an event in the past.

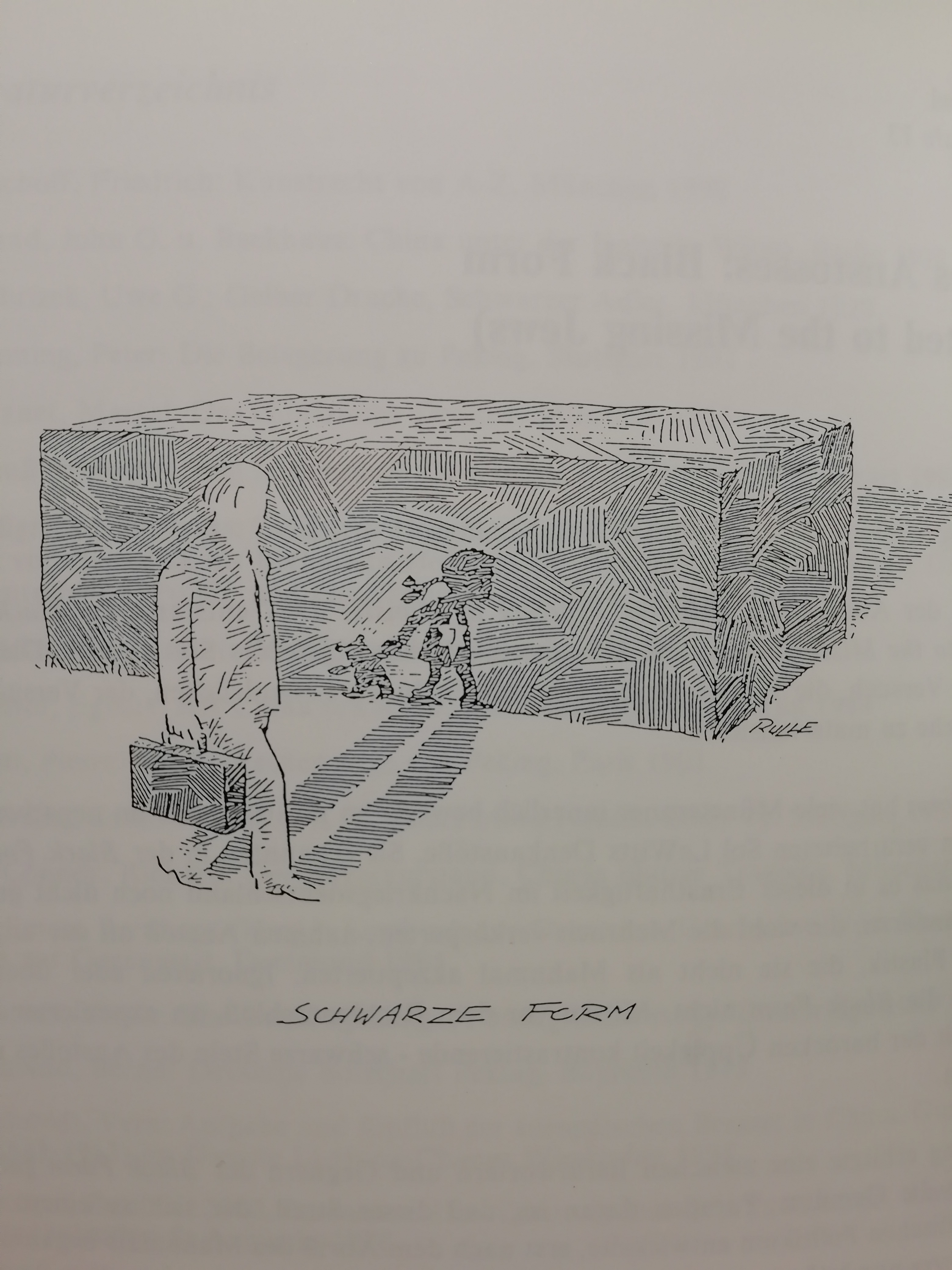

A black cube blocking a vista, marking a space once occupied by a memorial to Kaiser Wilhelm I – the Black Form seems laden with symbolism. Yet unlike a conventional memorial, it does not impart a clear message. Rather, it offers a space for reflection. It is a ‘counter-monument’ designed to force the viewer into an active role. As James Young has put it so aptly, ‘The most important “space of memory” for these artists [of counter-monuments] has not been the space in the ground or above it but the space between the memorial and the viewer, between the viewer and his or her own memory’. The cartoonist of Münstersche Zeitung captured this perfectly: he depicted a man carrying a black briefcase (like a miniature Black Form), who is passing by the actual Black Form. In his shadow, the man sees not a reflection, but the image of a young girl wearing the Yellow Star.

The Black Form and the debate it provoked sparked my own interest in the dynamics of commemoration generally and the symbolism of memorials in particular. Back in 1992–93, I did some research for which I interviewed a number of participants in the debate about the Black Form. Some five years after the destruction of the Black Form, and three years after German reunification, people were surprisingly eager to explain their position. The district president, the former rector of the university (who by then had become president of the German Rectors’ Conference) as well as the local party leaders – all busy people – agreed to be interviewed by a young student. The Holocaust, peripheral to the commemorative culture of the 1980s, was now at the heart of German post-national identity. What I learned from all this is that the meaning of a memorial is not set in stone. A visual marker, a memorial is embedded in a wider, often shifting discourse. And sometimes a debate surrounding a monument can be just as significant as the thing itself.

Stefan Goebel is director of the Centre for the History of War, Media and Society. His latest publication, co-written with Mark Connelly, is ‘Forgetting the Great War?’.

Image Credit 1: The destruction of the Black Form (Dedicated to the Missing Jews) on 24 February 1988 (LWL-Museum für Kunst und Kultur, Münster)

Image Credit 2: Cartoon ‘Schwarze Form’ by Andreas Rulle (Münstersche Zeitung, 5 November 1989).