Reviewed by Edward Corse

The Second World War produced some intriguing quasi-conflicts amongst the much larger and better-known battles of that period. Onur İşçi’s analysis of the relations between Turkey and the Soviet Union at that time carefully plots out one such fascinating story – one that is understudied and often misunderstood.

Drawing upon archives in Ankara, Moscow, Washington and London, including newly released material from the Turkish Diplomatic Archives (TDA), İşçi masterfully tells the story of how relations, which had been cordial during the interwar period, deteriorated rapidly once the war started. İşçi describes the change in relations as an ‘ugly metamorphosis’ (p. 174) and one which requires detailed analysis of relations both before and during the Second World War.

Indeed, İşçi spends almost a third of the book examining contacts in the interwar period. He demonstrates that relations had been strong with the founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, being grateful for the ‘guns, grain and gold’ (p. 165) the Soviet leader, Vladmir Lenin, had sent during the Turkish War of Independence. İsmet İnönü (then Turkey’s Prime Minister and later President during the war) made an official visit to Moscow in 1932, which helped bolster relations. Although ideologically far apart, the Soviets and Kemalists had formed an ‘anti-imperialist coalition’ (p. 2).

However, in the latter 1930s the geopolitical situation was changing and Turkey had identified Italy as the main threat to its sovereignty. Italy was militarising the Dodecanese Islands and invaded Abyssinia and later Albania – requiring Turkey to adopt what İşçi calls a ‘highly revisionist spin’ (p. 12). It did not help that the Soviets had signed a friendship pact with the Italian leader, Benito Mussolini, in 1933. With Italy increasingly active in the Balkans and Eastern Mediterranean – including through broadcasting fascist propaganda in Turkish – Turkey saw Britain, rather than the Soviets, as an effective counterbalance.

Although the Soviets signed the Montreux Convention in 1936, which regulated the management of the straits of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles, İşçi demonstrates that with Lenin’s successor, Josef Stalin, in place, the Great Terror resulted in experts in Turkey being ‘purged, imprisoned or executed’ (p. 48) in less than four months in 1937. Stalin was essentially surrounding himself with people who did not understand Ankara. The door was open for Britain to play a much bigger role in Turkish affairs, which led eventually to the Anglo-Turkish Declaration of April 1939.

Ankara was disillusioned by the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August 1939. Still, the Turkish Foreign Minister, Şükrü Saraçoğlu, travelled to Moscow in September after hostilities had broken out to see what could be agreed, only to be snubbed by Stalin. Turkey therefore took rapid steps to further develop its relations with the West. In October 1939 President İnönü signed a tripartite mutual assistance treaty with Britain and France ‘without even waiting for Saraçoğlu’s return from Moscow’ (p. 64).

Despite the tripartite agreement, however, Turkey did not join the war until its outcome was all but certain – remaining neutral until 23 February 1945 when a declaration of war became a prerequisite for joining the United Nations. İşçi sets out to explain why.

İşçi explains that, although the Italian threat remained important, İnönü feared Stalin’s intentions more and more. Stalin had invaded Poland, attacked Finland, the Baltic States, and Bessarabia in Romania – İnönü justifiably wondered whether Turkey might be next on Stalin’s hit list.

Nazi propaganda sought to capitalise on declining Soviet-Turkish relations through the publication of leaked telegrams by the former French Ambassador in Ankara, René Massigli – known as the ‘Massigli Affair’ – in the summer of 1940, whilst the Nazi-Soviet Pact as still in force. Massigli’s telegrams suggested that Saraçoğlu had been complicit in drawing up plans for the Allied bombing of the oilfields at Baku in Soviet Azerbaijan through allowing for the overflying of Turkish territory. İşçi notes that in response ‘the Soviets were levying all sorts of accusations against the Turks’ (p. 80) and mobilised troops on Turkey’s Eastern border. Following the Massigli Affair, relations never really recovered for the remainder of the war. İşçi insightfully states ‘Ankara began to look at Moscow through the lens of history and respond in terms of an older realpolitik. Nazi propaganda played a significant role in that process’ (p. 98).

On the eve of Operation Barbarossa, much to Britain’s displeasure, Turkey signed a friendship treaty with the Nazis, which essentially secured the Nazi’s southern flank and enabled Barbarossa to proceed without fear of attack by Turkey. Many in Ankara celebrated the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union. Saraçoğlu reportedly ‘danced to zeybek tunes until dawn’ on hearing the news (p. 73). However, Ankara did not abandon its mutual assistance treaty with Britain and repeatedly re-stated their commitment to it – including to the Nazis. Nevertheless, the ensuing Anglo-Soviet alliance and joint British and Soviet operations in Iran in August 1941 complicated Ankara’s position – and provided Nazi propaganda with plenty of material. Indeed, İşçi shows that ‘the Turks’ fear of Russia, in the British view, was never completely justified’ (p .147). Despite British pressure at the Adana and Cairo conferences in 1943, Ankara continually refused to move against the Nazis. Essentially, the Turkish government calculated that if Turkey ‘were to fight, it would merely weaken itself and increase the danger of becoming a satellite of Russia – like Poland’ (p. 146). Britain remained friendly with the Turks, but was exasperated by the lack of movement.

A particularly low point in relations between Moscow and Ankara centred around 24 February 1942. On that day the Soviets tried, unsuccessfully, to assassinate the German Ambassador to Turkey, and former Reich Chancellor, Franz von Papen. They also sank, in Turkish waters, the SS Struma carrying 769 Jewish refugees on their way to Palestine. As İşçi demonstrates, exactly how the Soviets were involved in both of these incidents was not clear for a long while. However, the Soviets were always, accurately, identified as culprits and this left ‘Turkish-Soviet relations irreparably damaged’ (p. 112). Turkey did not want to be dragged into the war against its will through incidents on its own soil and territorial waters.

İşçi shows that throughout the conflict the Turkish government sought to balance the interests of both the Axis and the Allies (including the Soviets). It was undoubtedly successful in keeping its territory intact from violation by the belligerents. Often Turkey has been portrayed as profiteering from the war – selling its goods and raw materials (especially chrome) and buying war materials from both sides. However, as İşçi demonstrates, the relations with all of the belligerents were far more complicated for the Turks to manage – especially in relation to the Soviet Union. Turkey was under pressure to yield from all sides and its economic situation was truly challenging. The situation was not helped by certain individuals, like the Turkish Ambassador in Berlin, Hüsrev Gerede, becoming a ‘self-appointed arbitrator’ (p. 129) in dealings with the Nazis. Not surprisingly, Gerede was dismissed by İnönü.

Much attention has naturally been given by historians to the issue of the straits and the Montreux Convention and how this was managed during the war. İşçi notes that this was indeed important, but he also highlights the importance of the threat to Eastern Anatolia in the Turkish government’s thinking. Some of the Turkish provinces there had been ceded to Turkey by Lenin, and İnönü feared that Stalin and Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had their sights set on restoring them to the Soviet Union. Late in the war, and once Turkey had actually declared war, a meeting between Molotov and the then Turkish Ambassador in Moscow, Selim Sarper, showed that İnönü’s fears were not unjustified. Molotov’s demands for the ceding of territory were, in İşçi’s words, ‘the last straw’ (p. 170).

İşçi dedicates an entire chapter to the rise of ‘Turanian Fantasies’. This essentially was the idea that all Turkic peoples (including Crimean Tatars and ethnic groups described by İşçi as ‘Eastern Turks’, many of which were located within the Soviet Union) should be united or connected in some way. Various versions of this idea had existed previously, but the idea had been ‘marginalized as a historical nexus’ (p. 125) by Atatürk. Atatürk instead wanted to secure Turkey’s borders, with a few exceptions, as they were agreed at Lausanne in 1923. During the Second World War there were a number of high-profile members of Turkish society, notably General Emir Erkilet, who had rekindled Turanian dreams. They naturally saw that the Nazis were their best hope of achieving those dreams at the expense of the Soviet Union. The dreams got nowhere, of course, due to the outcome of the war, but required careful management by the Turkish government particularly whilst the fate of the Soviet Union looked in doubt.

The most enlightening part of İşçi’s book is the argument that the deterioration in Turkish-Soviet relations during the war was actually an aberration. İşçi considers that the Turkish government reverted to the type of thinking that would have been more common in the previous Ottoman administrations. By contrast, İşçi argues that the cordial relations in the interwar period between Moscow and Ankara were a much better guide for what was ‘normal’ in the twentieth century. This initially seems like an odd argument – after all, Turkey famously joined NATO in 1952 and has remained a member ever since. However, with Stalin’s death, the frosty relations began to thaw and Molotov informed Ankara in 1953 that he was renouncing his previous demands for territory. During the 1960s relations improved further – and relations with the West declined, particularly over Cyprus. İşçi argues that ‘antagonism was not the default mode in the Soviet-Turkish exchange’ and ‘Turkey’s unduly pro-Western and anti-Soviet direction in the 1950s marked a radical departure from the grand strategy’ devised by Atatürk (p. 175).

İşçi’s analysis and insights are a fascinating read and important for those wishing to understand the challenges faced by a neutral country in the Second World War. Turkey was surrounded on all sides by belligerent activity, but was successful until near the very end in keeping out of the war entirely, and even then did not play an active part in the military operations. The relations between the Soviet Union and Turkey were tense but were ultimately managed away from conflict even at the most testing of times.

Turkey and the Soviet Union during World War II: Diplomacy, Discord and International Relations, by Onur İşçi (London: I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury Academic, London, 2020; 256pp.; £85.00)

Edward Corse is an Honorary Research Fellow of the Centre for the History of War, Media and Society at the University of Kent and the author of A Battle for Neutral Europe: British cultural propaganda in the Second World War (Bloomsbury, 2013). He is one of the convenors of the ‘Propaganda and Neutrality: alternative battlegrounds and active deflection’ conference taking place online on 24-25 June 2021

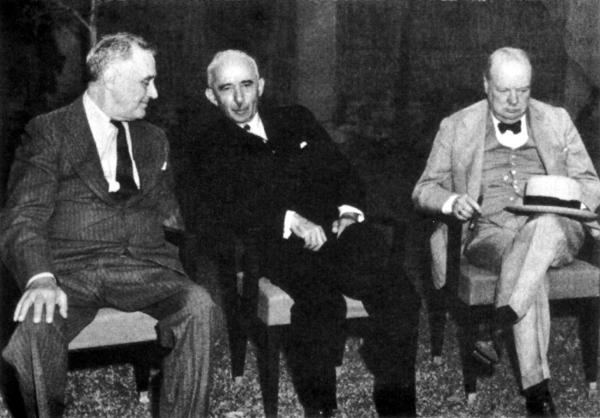

Image Credit: President Roosevelt, President İnönü and Prime Minister Churchill at the Second Cairo Conference, 5th December 1943. Licence: Public Domain