Written by Mark Hurst.

In a contemporary climate dominated by fake news, political spin and online legions of anonymous figures fighting information wars, it is apparent that a question repeatedly posed may come to define the era: What information do we trust? This was at the forefront of the campaigns conducted by human rights activists during the Cold War, who sought to support persecuted prisoners of conscience by obtaining reliable and trusted information on human rights violations and using this material to petition positions of power to put pressure on oppressive governments.

In the case of the myriad of campaigns against the human rights violations conducted by the authorities in the Soviet Union, experts affiliated with Non-Governmental Organisations built their reputation through years of diligent scholarly activity. This was often conducted in relative silence, allowing information collected from sources in the Soviet bloc to ‘speak’ for itself. Amnesty International is perhaps the most notable organisation that attempted this apolitical stance during the Cold War, focusing on the suffering of the individual rather than the broader political issue at hand. Its researchers produced numerous reports, bulletins and calls for urgent action based on politically charged material from around the world, yet the organisation insisted that it was impartial – something that won it many supporters.

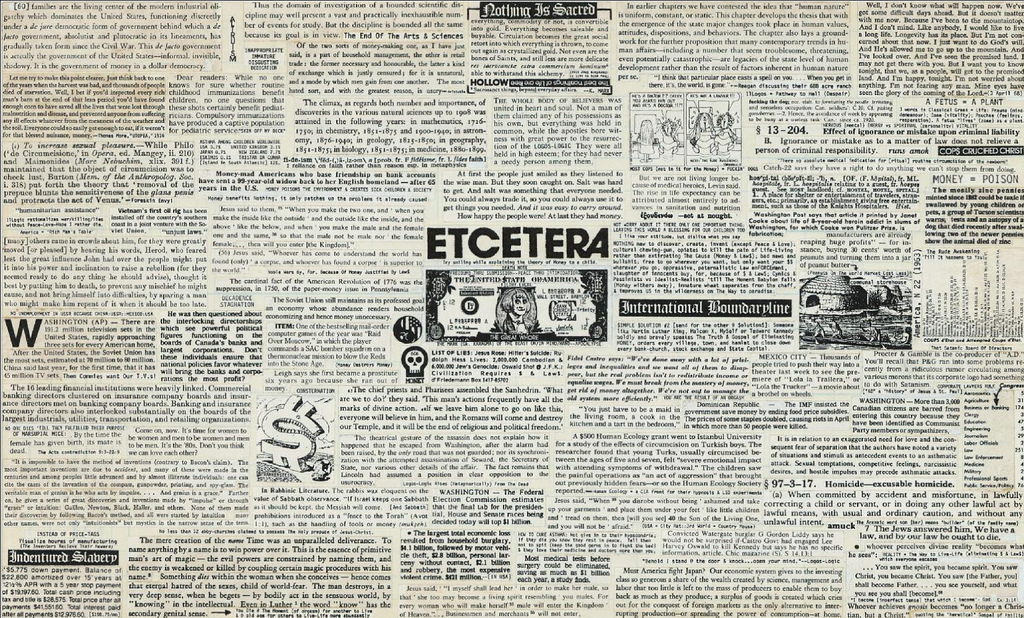

Political dissidents in the Soviet Union followed this example, circulating information they had on human rights violations through underground samizdat – self-published pieces – on the circumstances that they faced. Samizdat was typically ideologically motivated, highlighting the political ideals of its authors. The Chronicle of Current Events (Khronika Tekushchikh Sobytii), however, stood out due to its objective approach in listing the Soviet authorities’ efforts to persecute its opponents. The Chronicle ran from April 1968 through to December 1983 and provided a vehicle through which human rights violations could be reported to a wide audience. Trust in the Chronicle was established through its impartiality, a trait that is arguably implausible in the age of fake news.

It is perhaps testament to the increased pressure on political activists in contemporary Russia and the rise of fake news that this historical legacy is being resurrected in a New Chronicle (Novaya Khronika Tekushchikh Sobytii). How successful this outlet will be is yet to be seen, but its attempt to tap into the Chronicle’s legacy is perhaps telling of a craving for truthful, impartial and trusted information in an age of disinformation. This is part of a broader narrative of contemporary political activists such as Pussy Riot and Petr Pavlensky placing themselves as the heirs of the dissident movement, doubtless in an attempt to draw from their legacy.

Amnesty, on the other hand, has moved in a different direction, increasingly becoming a slick media organisation more concerned with online ‘clicktivism’ and campaigning through social media channels, moving away from its concern with collecting information on its adopted ‘Prisoners of Conscience’. Whilst this has doubtless raised the group’s profile online, it could be argued that this approach might sacrifice its reputation for reliability. Time will tell how it will be impacted by this transition, and whether the public will continue to trust its information in the future.

Mark Hurst is a Lecturer in the History of New Social Movements/Alternative Cultures at Lancaster University and the author of British Human Rights Organizations and Soviet Dissent, 1965-1985 (Bloomsbury, 2016)

Image Credit: CC by Raquel Baranow/Flickr.