Written by David Welch.

When in the 1970s I began my doctoral research into the Nazi cinema there were few fellow travellers working in the field of propaganda. I was lucky to find Philip Taylor who had started his work on British propaganda during the inter-war period at the same time as me. In spite of the fact that he supported Liverpool and held Spurs in low esteem we became firm friends and collaborators until Phil’s untimely death in 2010. During the Cold War in the 1950s and 60s, the study of propaganda was largely linked to the respective ideological blocs and propaganda continued to have pejorative connotations. The far-reaching impact of the Cold War led to new political and sociological theories on the nature of man and modern society. Individuals were viewed as undifferentiated and malleable while an apocalyptic vision of mass society emphasised the alienation of work, the collapse of religion and family ties and a general decline of moral values. Accordingly propaganda was viewed as a ‘magic bullet’ or hypodermic needle’ by means of which opinion and behavior could easily be controlled. In 1965, the French sociologist Jacques Ellul published his ground-breaking work Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes. Ellul argued that propaganda was not a homogenous term but embraced a host of subtleties that included political propaganda but also what he termed ‘integration’ propaganda. Ellul cited the example of the way in which America exported its way of life and values through its films and television. Historians now began to work on cultural artefacts as examples of propaganda. Two early examples were Jeffrey Richards’ Visions of Yesterday (1973) which showed how society (American populism, British imperialism, German Nazism) is consciously or unconsciously, mirrored in its cinema, and Richard Taylor’s The Politics of the Soviet Cinema (1979) that demonstrated the importance of the cinema in projecting Bolshevik ideology. At the same time, the newly established Open University (‘university of the air’) pioneered the innovative use of film, radio and television in its interdisciplinary courses and helped produce the Inter-University History Film Consortium which brought together a pioneering group of British, German, Dutch and Danish scholars and marked the beginning of many years of fruitful collaboration.

The catalyst was the formation in 1977 of the International Association for Media and History (IAMHIST) which held its first bi-annual conference in 1979. The inaugural issue of its official interdisciplinary journal the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television (HJFR&T) was published in 1981 under the editorship of K.R.M. Short and I had the honour of authoring article 1 with my study of ‘The Proletarian Cinema and the Weimar Republic’. Quite by chance, I also edited the Journal’s twentieth anniversary issue on ‘News into the Next Century’. My two publications in the Journal sum up the enormous scope and interdisciplinary nature of the study of propaganda during these twenty years. The Journal has continued to act as an important vehicle for historians and social scientists interested in the impact of mass communications on the political and social history of the twentieth century. I note that the Journal’s 35th special issue at the end of 2015 was based on a conference sponsored by Centre for the Study of War Propaganda and Society on ‘The Great War and the Moving Image’.

The scholarly work published in the HJFR&T inevitably had an impact on the study of propaganda. In 1990, Phil Taylor established the Institute for Communication Studies at Leeds and four years later I set up the Centre for the Study of Propaganda at Kent. Both centres attracted a new generation of historians working in the field of propaganda studies who went on to forge distinguished academic careers: Nick Cull, Susan Carruthers, Gary Rawnsley, Martin Doherty and Jo Fox to name a few.

New scholarship also challenged old assumptions. The ‘hypodermic needle’ theory has largely been replaced by a more complex ‘multistep’ model that acknowledges the influence of the media yet also recognises that individuals seek out opinion leaders within their own social class and gender. Most writers today agree that propaganda confirms rather than converts – or at least is more effective when the message is in line with existing opinions and beliefs. This shift in emphasis underscores a number of common misconceptions connected with the study of propaganda. There is a widely held belief that propaganda implies nothing more than the art of persuasion, which serves only to change attitude and ideas. This is undoubtedly one of its aims, but it is usually a limited and subordinate one. Propaganda is as much about sharpening and focusing on existing trends and beliefs. A second basic misconception is the belief that propaganda consists only of lies and falsehood. In fact, it operates on several levels of truth – from the outright lie to the half-truth to the truth out of context (Officials in the Ministry of Information in World War II referred to this as the ‘whole truth, nothing but the truth – and as near as possible the truth!’). Many writers on the subject see propaganda as essentially appeasing the irrational instincts of man – and this is true to a certain extent – but because our attitudes and behaviour are also the product of rational decisions, propaganda must appeal to the rational elements in human nature as well. The preoccupation with the former ignores the basic fact that propaganda is ethically neutral – it may be good or bad. This was the founding cornerstone of the Centre for the Study of Propaganda (now Centre for the Study of War, Propaganda and Society) when it was initiated in 1994 and it has remained so ever since.

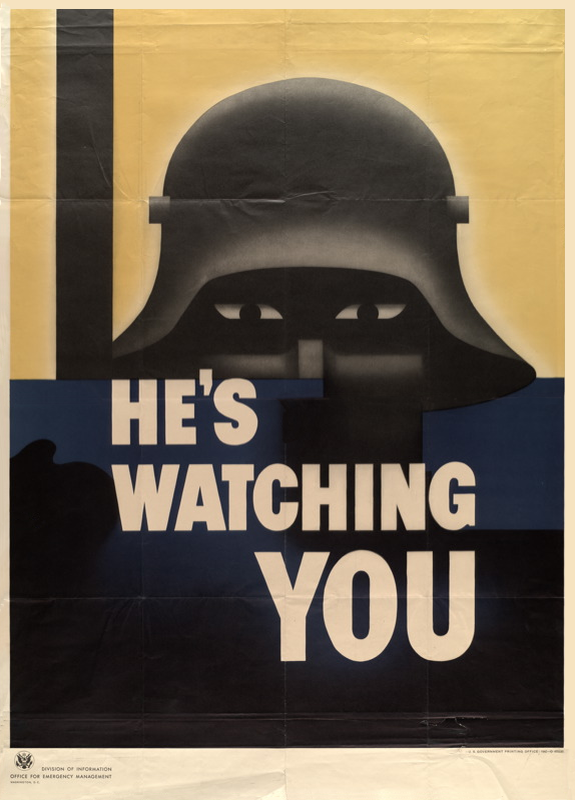

In 2013, I co-curated for the British Library the first major exhibition held in Britain on ‘Propaganda. Power and Persuasion’, which attempted to encourage the public to think more critically about the nature of propaganda – from both a historical and contemporary perspective. It proved both controversial and popular. The exhibition started with the Ancient Greeks and the ‘art of persuasion’ and ended in the age of Facebook and Twitter by asking the question; ‘Are we all propagandists now?’ It is a question I would like to return to in a future blog.

David Welch is Emeritus Professor of Modern History and Honorary Director of the Centre for the Study of War, Propaganda and Society at the University of Kent. Image credit: CC by Jay Pitsby/Flickr