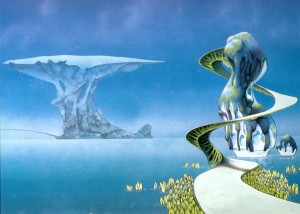

Ah, the beguiling Elysian fields of the gatefold-album. The grand vistas which floated into view at the marvellously magical moment of opening the twin record-sleeves for the first time. There’s something almost awe-inspiring, a religiosity about opening up a gatefold LP album for it to occupy a space wider than your own head. It’s something of an immersive experience, allowing you to explore the fascinating, intricate details of the album cover (particularly important with, for instance, Roger Dean’s artwork for Yes albums, and a feature of prog-rock). In fact, the wider vistas which the gatefold created were perhaps integral to the nature of the concept album, and the mystical synergy which allowed partnerships like Yes and Dean to craft a product where the outside mirrored, nay, even enhanced the inside.

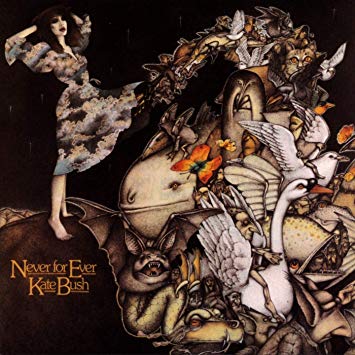

The gatefold packaging of rock music, and of prog-rock in particular, demanded that you gave yourself over entirely to listening to an album, and the information often packed into the densely-loaded inner vistas which gatefold packaging offered turned the consumption of an album into a total immersion-type experience; you submitted yourself entirely to the sonic, visual and textual odyssey, surrendering the senses in an entirely legal (though not necessarily non-addictive) way. I remember one of the earliest gatefold LPs I ever bought, Never for Ever by Kate Bush, which features a plethora of animals, both real and mythical, bursting unstoppably from beneath the songstress’ skirt.

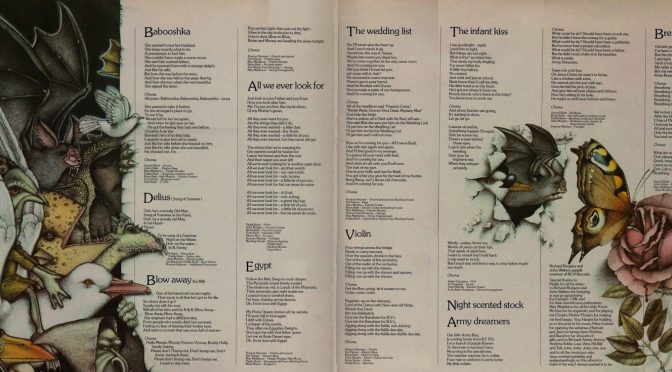

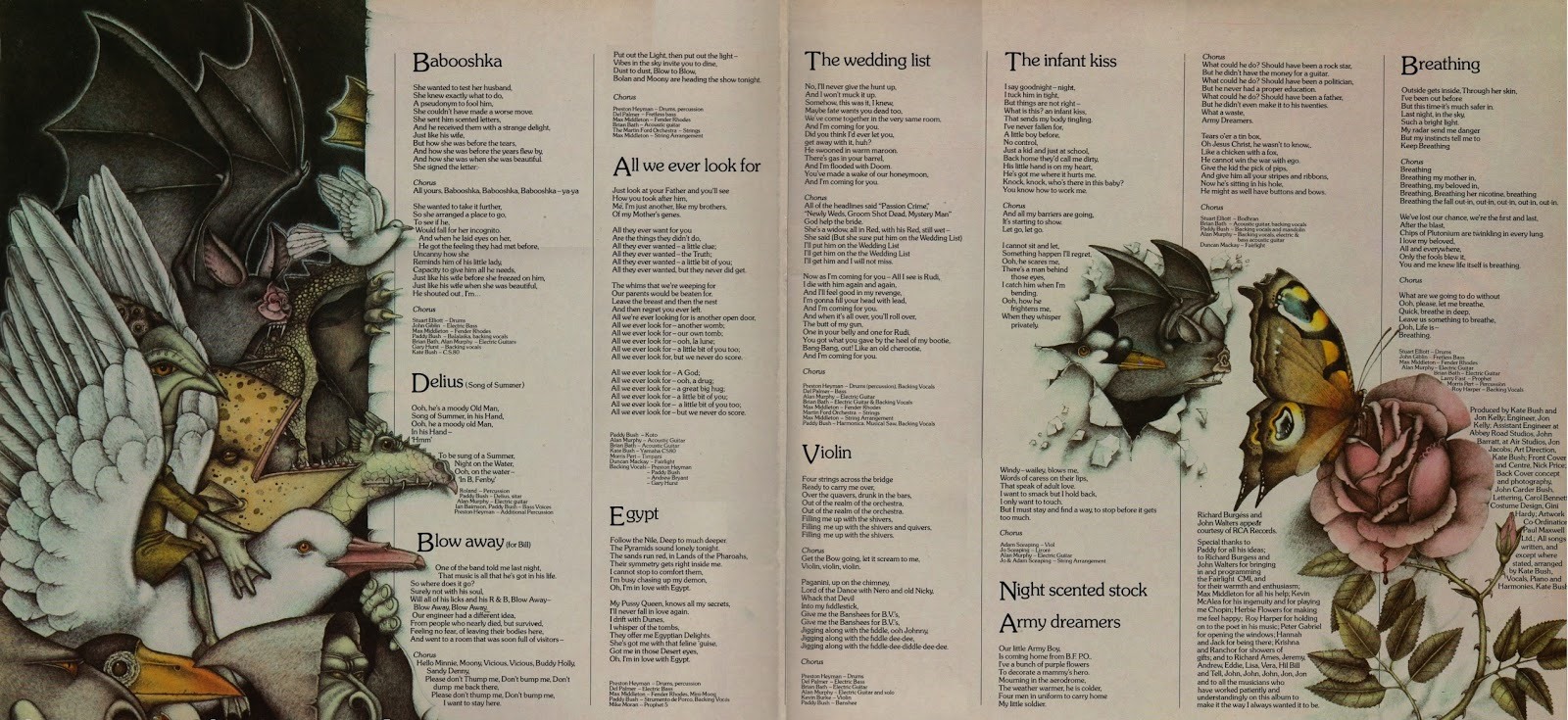

Bats, birds and butterflies adorned the inner covers, either hovering above them or seeming to burst through from the other side (I loved the implied three-dimensionality there), and there was now the chance (as always) of pressing your nose up against the lyrics to try and decipher their meaning. Was it THAT Delius about whom she was singing ?

Bats, birds and butterflies adorned the inner covers, either hovering above them or seeming to burst through from the other side (I loved the implied three-dimensionality there), and there was now the chance (as always) of pressing your nose up against the lyrics to try and decipher their meaning. Was it THAT Delius about whom she was singing ?

Jazz, too, embraced the gatefold packaging; who can forget the back cover of Weather Report’s 8.30 featuring the band casually sitting around engaged in a whose-shoes-are-the-longest competition, clearly won by Jaco Pastorius in those impossible, never-ending, glowing-white winkle-pickers ?

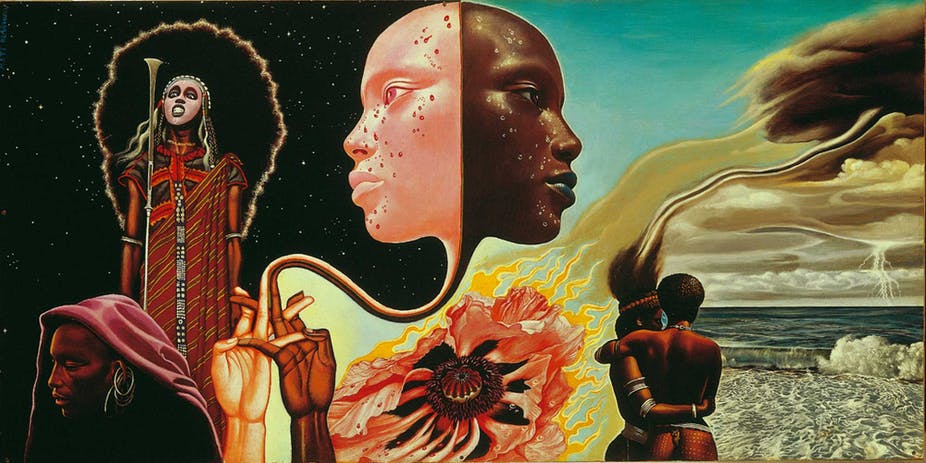

Or the mysterious, hallucinatory, swirling panorama (perfectly mirroring the music) that appeared when you opened up Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew and saw front and back covers side-by-side, turning into a single yin-and-yang image, featuring what seemed to be a high priestess and acolyte engaged some sombre ritual on the left, mirrored by a couple standing in the surging surf beneath an ominously-looming sky on the right ?

Contrastingly, there was African Sun by pianist Dollar Brand, that offered the opportunity to sink into the front cover’s warm, orange glow.

Contrastingly, there was African Sun by pianist Dollar Brand, that offered the opportunity to sink into the front cover’s warm, orange glow.

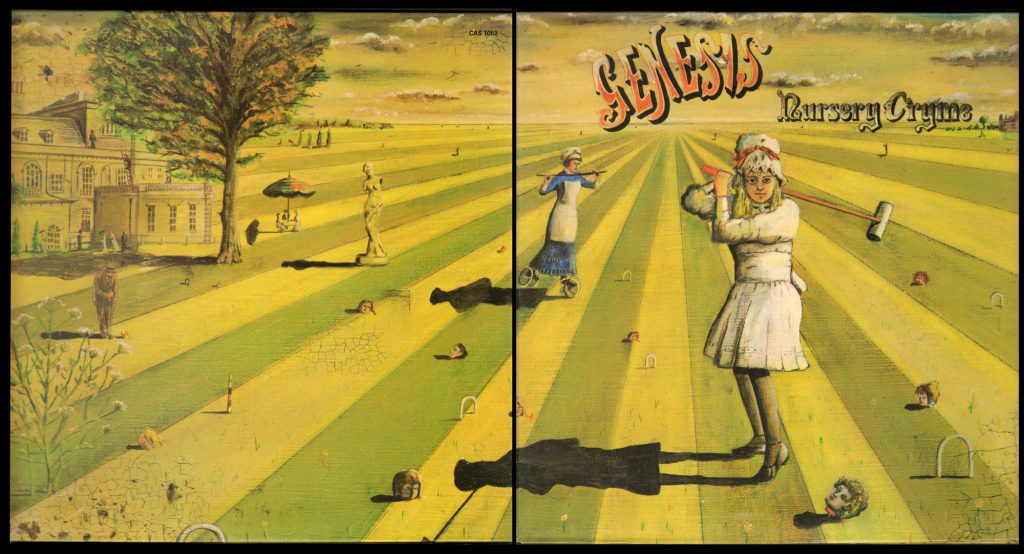

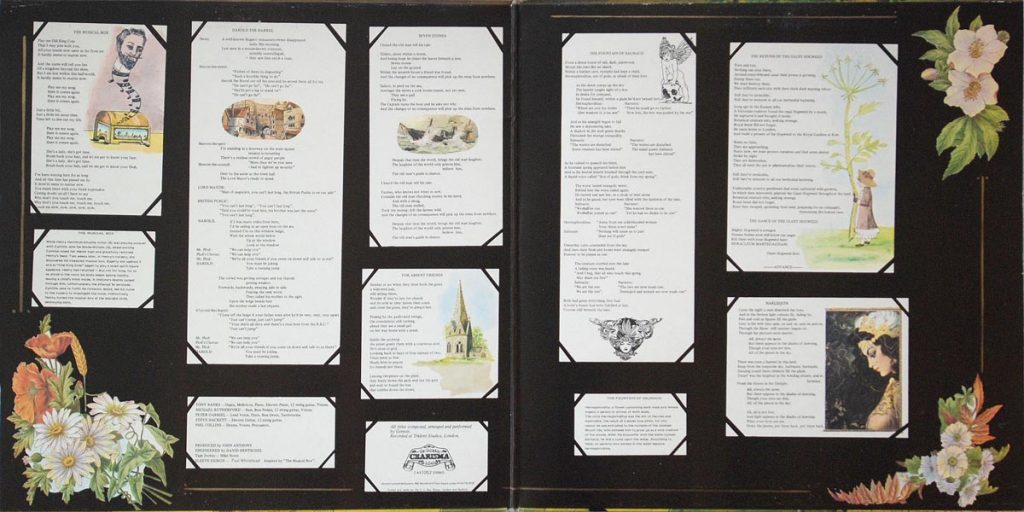

Rather than simply printing the lyrics to the songs and the band line-up, prog-rock positively luxuriated in the creative possibilities afforded by gatefold’s inner and outer covers, and it was also a way for puzzled fans to really scrutinise the mytho-poetic lyrics, and really get to grips with all the references and the pastoral imagery of something like Nursery Cryme, from Genesis in its early years. Following the magnificent perspective of a impossibly-well manicured lawn hosting a malevolent-looking game of croquet, you flipped over to the inside of the sleeves to reveal what looked like a collection of postcards, complete with chintzy illustrations, each as though tucked into a presentation portfolio by its corners. The bearded figure emerging on a current of notes escaping from ‘The Musical Box;’ the mock-Victorian image for ‘The Return of the Giant Hogweed’ showed an innocent young girl standing by a towering weed. And now you could follow the words to ‘The Fountains of Salamacis.’

Or Foxtrot, Genesis’ next album release; you could follow the complicated narrative of ‘Supper’s Ready’ by perusing the lyrics, which unfolded against a (deliberately misleading) background of blue skies and fluffy clouds. And as prog-rock sank beneath the weight of its own over-inflated self-aggrandisement, heavy metal came in to occupy the void that it left behind.

Or Foxtrot, Genesis’ next album release; you could follow the complicated narrative of ‘Supper’s Ready’ by perusing the lyrics, which unfolded against a (deliberately misleading) background of blue skies and fluffy clouds. And as prog-rock sank beneath the weight of its own over-inflated self-aggrandisement, heavy metal came in to occupy the void that it left behind.

(A shameful admission here; I also had the double-LP Livin’ Inside Your Love by George Benson (I know, I know…), which I bought when I discovered that he was the guitarist on Miles Davis’ Miles in the Sky, and rushed out to find something else by him (I should have done some more research first, shouldn’t I…); the LP’s soft-focus cover should have been a clue, hinting at the soft-focus music contained therein…sigh… )

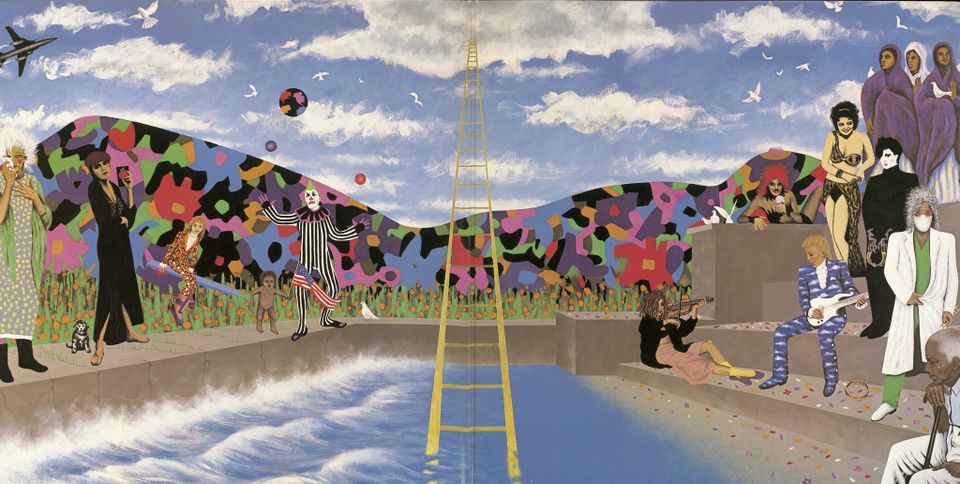

Prince, too, saw the potential for gatefold’s symbolist evangelising, in his Around the World In a Day (although the album, like Never For Ever was only one LP, rather than two); the cover is packed with references to the songs in a slightly trippy evocation of the mythical Paisley Park itself.

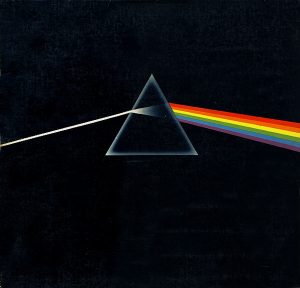

There’s a fascinating quote by (if memory serves) keyboardist Nick Mason (in Dark Side of the Moon: the making of a Pink Floyd Masterpiece by John Harris), who observes that the publicity opportunity afforded by the album’s presentation was missed; you could open the album out and have it leading across front and back covers in continuous fashion, an effect that he says would have looked spectacular in record shops, only no-one noticed the potential to display it so. (My copy is currently in the loft, and I only have the one so sadly can’t endeavour to create this phenomenon for myself to see the effect…)

There’s a fascinating quote by (if memory serves) keyboardist Nick Mason (in Dark Side of the Moon: the making of a Pink Floyd Masterpiece by John Harris), who observes that the publicity opportunity afforded by the album’s presentation was missed; you could open the album out and have it leading across front and back covers in continuous fashion, an effect that he says would have looked spectacular in record shops, only no-one noticed the potential to display it so. (My copy is currently in the loft, and I only have the one so sadly can’t endeavour to create this phenomenon for myself to see the effect…)

Regrettably, cassettes and, later, CD reissues couldn’t offer the same escapism; it was impossible to immerse yourself in liner notes from a CD jewel-case that, when opened out, barely covered both your hands. The printed lyrics were tiny, and the amount of detail in those prog-rock, symbol-saturated album covers was lost at so small an incarnation. I bought Miles Davis’ fearsome jazz-rock album, Live-Evil, on CD years later, which endeavoured to recreate the mystique of the gatefold LP with an unfolding four-sides cardboard presentation style, but it wasn’t the same; it lacked the imperiousness of the LP’s sheer physical presence. And don’t even get me started on the (literally) unfolding, multi-level misery of Prince’s Emancipation on cassette…

I’ve necessarily limited this to a discussion of some of the albums I have, or used to have (there’s also somewhere in my loft Queen’s A Night At The Opera and, I think, Sheer Heart Attack, and Tippett’s impenetrable opera, The Knot Garden, plus Joni Mitchell’s eminently forgettable Chalk Mark in a Rainstorm, in gatefold format); a full examination of the Gatefold Phenomenon would take years, and embrace such thorny issues as what was the FIRST gatefold release (do you include 78s that were released in this way ?) – Bing Crosby, Elvis, Bob Dylan ? – what was the most controversial (Bowie’s Diamond Dogs, Black Sabbath’s self-titled album ?) – what about gatefold inner covers that just featured a nicely-pleasing photo of the band (Seargent Pepper ?) rather than going down the whole concept-art-tunnel ? Do you include albums that only had one LP rather than being a double LP release, the latter arguably a more justified reason to package with two sleeves ? You see what I mean…

These days, of course, streaming and digital platforms have all but rendered the physical presentation of an album obsolete, sacrificing (in my view) the ability to play whatever you want, whenever you want on your digital device for the sheer, tangible, pleasure of the impact of the album’s artwork. But vinyl is making a comeback – time for Gatefold Novices to get out there and experience the heady delights, that transcendent rapture, of unfolding a double LP on its first playing…