As part of the Alice in Wonderland project by the Music department this year, the programme to the performances includes an essay on domestic music-making during the nineteenth-century by Dr Siobhan Harper. An alumna of the University of Kent and former Music Scholar, Siobhan read English Literature at Kent and graduated in 2009; she obtained her PhD in Victorian Literature at the University of Durham, and in the essay examines the role of music, and its portrayal in literature, during the era in which Alice in Wonderland was first published. Her essay, which features in the programme accompanying the performance of the Musical Dream Play, appears here in its entirety.

‘A sound of music issued from the drawing-room’: Domestic Parlour Music and Beyond in the Nineteenth Century and its Literature

England in the nineteenth century was known as ‘Das Land ohne Musik’ – the land without music. This is, of course, a ludicrous claim, and one that was heavily contested by musicologists at the time; there is ‘no doubt that professional and domestic music-making was an important part of daily life’.[1] So much so, indeed, that ‘much of the literature of the period is rich with musical scenes and themes’, with ‘novels throughout the century […] brimming with scenes at the piano’.[2]

The British were, however, ‘musical and not musical, depending on the speaker’[3] – and, more importantly, the subject. Music was for ‘women, foreigners, industrial workers, and professional musicians’, to the extent that it was considered an ‘emasculating [and] debasing activity for men of the aspiring middle classes and nobility to practise’; men of these classes were the audience only, always distanced.[4] Music was, then, ‘largely gender specific’, since it ‘was one of the few fields in which most middle- and upper-class girls were educated, and boys were not’.[5] As such, it was inextricably tied up with ‘perceptions of ideal femininity’.[6]

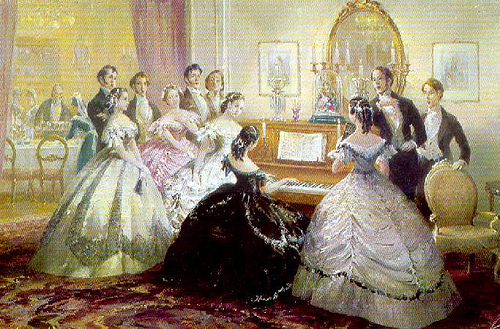

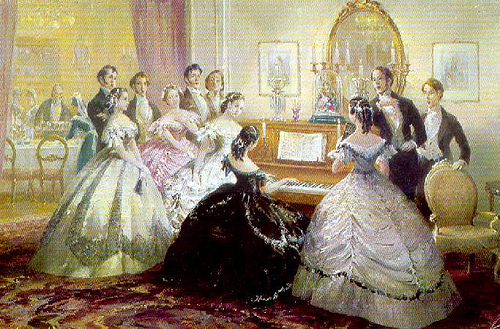

It was domestic music that dominated the first half of the nineteenth century, and ‘any household that could afford one was likely to possess a piano’.[7] But owning a piano was about far more than the instrument itself: it indicated that ‘not only can the family afford a piano, sheet music, lessons and leisure time, but the choice of instrument, the piece being played, and [the pianist’s] manner of execution all communicated her genteel taste, or lack thereof’.[8] The piano, its player, and all of the accoutrements therefore ‘visibly and audibly demonstrated a man’s respectable social standing and financial well-being to those who shared the same cultural capital’.[9]

The quotation above specified ‘her genteel taste’ with good reason – for it was always her. The piano was the middle-class luxury ‘most significant in the lives of women’; it was ‘an emblem of social status’, a ‘gauge of a woman’s training in the required accomplishments’, and ‘its presence afforded women a particular distinction within domestic culture’,[10] as girls and women ‘performed for select gatherings of peers after dinner’.[11] And while men of this class certainly sang – think of Frank Churchill in Jane Austen’s Emma (1815), who is ‘accused of having a delightful voice, and a perfect knowledge of music’, and Mr Rochester in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), who ‘has a fine bass voice, and an excellent taste for music’ – this was generally only when accompanied by, and often duetting with, a woman. The most prominent male pianist exhibited in the literature of the period is Herr Klesmer, in George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda’s (1876), who is at once both foreign and a professional musician and music teacher; an outsider in two respects.

The performers of choice in the middle- and upper-class home were unmarried daughters, to the extent that ‘it seems that the greater use of amateur music was to obtain a good marriage’.[12] After all, as William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848) espouses, what else could cause young people ‘to labour at pianoforte sonatas, […] and to play the harp if they have handsome arms and neat elbows, […] but that they may bring down some “desirable” young man with those killing bows and arrows of theirs?’. After-dinner or social performances in the parlour ‘presented potential suitors with an opportunity to watch a young lady’s graceful and beautiful movements, […] and/or to note her father’s social status which allows her enough leisure to practise music’.[13] But it was just as important for these young women to play appropriately as it was to play well: daughters playing ‘rigorous works which required virtuosic skill […] brought censure’,[14] and being ‘too technical is equated with being unladylike’.[15] Not least of the reasons for this was because ‘most male audience members were musically illiterate’,[16] and desired a wife with musical skill in order to relax and soothe, as Tertius Lydgate, of George Eliot’s Middlemarch’s (1873), muses that the society of a wife should be like ‘reclining in a paradise with sweet laughs for bird-notes’.

In addition to the music itself, the instruments that women were allowed to play were carefully regulated. The ‘model young lady sang and/or played the piano, the harp, or the guitar’; these instruments ‘were thought to display the player’s posture and movements advantageously’, and so ‘assisted the family’s upward mobility’ by way of their daughters’ advantageous marriages.[17] Violins were objected to on the grounds that ‘the players looked unattractive’,[18] and ‘the flute was especially problematic because of its shape’, which had been ‘a favourite symbol of masculinity’ during the eighteenth century. Given the disapproval of the flute for female musicians, we can only assume that the clarinet would have met with even worse favour due to the angle at which it is played; the bassoon due to its size; and the cello due to its unfortunate positioning between the legs. History does not relate the culture’s opinion of the piccolo, and one wouldn’t care to speculate whether its size would have made it more or less acceptable in the eyes of those who thought the flute too suggestive.

Despite the limited range of instruments available for amateur middle- and upper-class women, and although the piano held ‘indisputable prevalence … in the home’,[19] it is important to note that domestic music comprised more than just this instrument. String quartets also found a place in the parlour, principally made up of male amateurs or male professionals, and some with accompaniment from a female pianist.[20] A writer in 1924 ‘[deplored the] public’s ignorance of wind chamber music’ in the preceding century,[21] so it seems that this was much less popular for a home environment. These examples are few; but while it’s certainly true that domestic music remained firmly under ‘the smothering influence of the parlor piano, the ubiquity of which is impossible to deny’,[22] their existence does demonstrate that this was not a hegemony.

As the century wore on, however, the consumption of and knowledge surrounding music began to change. The school curriculum widened in 1839 to formally include music lessons.[23] The lower classes experienced wage increases, particularly in the 1860s to 1890s, while, concurrently, ‘music for the masses grew at unprecedented rates’.[24] Band competitions started in 1853 with the Belle Vue Contest, choir festivals began in 1855 in Manchester (excluding the notable history of Welsh choir competitions, of course), and ‘by the end of the century, there were thousands of brass bands and choral societies in Britain’.[25] More people were able to ‘participate in music-making’, and, importantly, ‘concert attendance rose mid-century as rural and urban workers took advantage of this newly available entertainment’.[26] An 1860 article in Macmillan’s magazine examined this phenomenon as it happened:

Not many years ago an orchestral symphony or a stringed quartet [sic] were luxuries hardly to be indulged in by those Londoners whose guineas were not tolerably numerous. Times are changed for the better; and not a week passes, even in the dullest season of the year, that some good music is not to be heard at a cheap rate in London.[27]

Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1855) alludes to this phenomenon as it affected northern cities; the fictional town of Milton (modelled on Manchester) has ‘good concerts’, though Fanny Thornton complains that they are ‘too crowded’ since ‘the directors admit so indiscriminately. But one is sure to hear the newest music there’.

There was at this point so much ‘performed music … available to an increasingly mobile […] audience by the middle of the nineteenth century’[28] that it was almost inevitable that the number of players of music would increase in a similar fashion. Pianos began to be ‘affordable by families further down the social scale’,[29] which was unacceptable to the classes of women for whom the piano had been theirs; there was suddenly ‘a need to secure a respectable domestic instrument for women from the upper social classes’ as a result.[30] By the 1870s, the violin’s grace overruled the unattractive appearance of the players, and women were permitted to take up this instrument.[31] Similarly, the flute was deemed acceptable for women once the phallic symbolism was overcome by supporters of female flautists encouraging focus ‘on the flute’s sound rather than the flautist’s picture’.[32] And ‘the cultural unacceptability for women to learn string instruments’ as a whole ‘finally crumbled around 1870’, and ‘many middle- and upper-class women took up the violin, viola, and cello’ as a consequence.[33]

Domestic music did not wane, but music consumption outside of the home widened and diversified hugely. The first performance of Alice in Wonderland: A Musical Dream Play for Children and Others in 1886 is situated in the centre of this expansion of music in the period. The musical choices made for this performance echo, without mimicking, the forms that domestic, amateur music-making took in the period; while remaining faithful to the musical styles of the period, these musical choices also succeed in evoking the changes that were occurring musically as the nineteenth century progressed. The small instrumental ensemble is reminiscent of the piano-accompanied performances, while the presence of the flute, clarinet, and bassoon are representative of the diversification of instruments and types of performance that occurred outside of the home, particularly in the last four decades of the period. Moreover, that the flute and bassoon are played by women gives more than a passing nod to the ‘cultural unacceptability’[34] of these instruments for female performers – even, or perhaps especially, in a private, domestic setting – only 150 years ago.

It is surely impossible to give an impression of a whole century’s musical fashions, endeavors, and habits; such an expanse would not be easily captured. The musical choices made here are, however, both gloriously resonant of the enduring and venerated domestic parlour performances, and evocative of the sweeping and significant musical expansion that marked the last half of the nineteenth century. All this pouring forth from ‘Das Land ohne Musik’.

© Dr Siobhan Harper January, 2020

Bibliography

Baron, John H., Chamber Music: A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2010).

Bashford, Christina, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Summer 2010), pp. 291-360.

Burgan, Mary, ‘Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction’, Victorian Studies 30.1 (Autumn 1986), pp. 51–76.

Clapp-Itnyre, Alisa, Angelic Airs, Subversive Songs: Music as Social Discourse in the Victorian Novel (Ohio, Ohio University Press, 2002).

da Sousa Correa, Delia, George Eliot, Music and Victorian Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003).

Gray, Beryl, George Eliot and Music (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989).

Weliver, Phillis, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900: Representations of music, science and gender in the leisured home (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2000).

[1] Weliver, Phillis, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900: Representations of music, science and gender in the leisured home (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2000), pg. 19.

[2] Clapp-Itnyre, Alisa, Angelic Airs, Subversive Songs, pg. xv.

[3] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 20.

[4] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 19.

[5] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 21.

[6] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 1.

[7] Gray, Beryl, George Eliot and Music (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1989), pg. 1.

[8] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 33.

[9] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 33.

[10] Burgan, Mary, ‘Heroines at the Piano: Women and Music in Nineteenth-Century Fiction’, Victorian Studies 30.1 (Autumn 1986), pp. 51–76, pg. 51.

[11] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 33.

[12] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 33.

[13] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 33.

[14] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 34.

[15] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 36.

[16] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 37.

[17] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 47-8.

[18] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 48.

[19] Bashford, Christina, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Summer 2010), pp. 291-360, pg. 303.

[20] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 307.

[21] Baron, John H., Chamber Music: A Research and Information Guide (New York: Routledge, 2010), pg. 94.

[22] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 312.

[23] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 28.

[24] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 27.

[25] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 28.

[26] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 28.

[27] ‘Classical Music and British Musical Taste’, Macmillan’s, quoted in Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 29.

[28] Gray, George Eliot and Music, pg. 1.

[29] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 317.

[30] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 317.

[31] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 48.

[32] Weliver, Women Musicians in Victorian Fiction, 1860–1900, pg. 50.

[33] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 294.

[34] Bashford, ‘Historiography and Invisible Musics: Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, pg. 294.