Ah, the thorny question: how does music mean ? Can it have external meaning, or does meaning derive solely from its internal content – harmony, tonality, the working out of ideas ? Does it – indeed, can it – express ideas, emotions, characters, or does it simply ask the listener to follow the unfolding events, the order of ideas and the relationships between them ?

Leonard Bernstein offers some thoughts in a lecture from Harvard:

As he says: ”Music does possess the power of expressivity (sic).” Whether, like Stravinsky, you feel that music is “by its very nature, powerless to express anything at all” (1) (Stravinsky was talking about his so-called ‘white’ music at the time, such as the ballet Apollon Musagete: Variation de Calliope for strings), or that music conjures its meaning from associations brought by the listener (i.e. previous experiences of similar chords and keys), music certainly has the power to move listeners. A listener with a half-decent wealth of listening experience perhaps comes to a piece with all that listening and its commensurate baggage: one melodic shape reminds them of another piece they’ve heard, a particular sonority or chord reminds them of another piece in which they’ve heard it, or a tonality is associated with a certain mood or frame of mind.

Bernstein distinguishes between ‘what music expresses’ and ‘how music expresses it’ by talking about metaphor, music as a language rich in metaphor, ‘meaning beyond the literal.’

Leonard B. Meyer’s Emotion and Meaning in Music defines two types of listener: those for whom musical meaning “lies exclusively within the work itself, in the perception of the relationships set forth within the musical work of art” and those for whom music also “communicates meanings which in some way to the extramusical world of concepts, actions, emotional states and character.” Meyer calls the former ‘absolutists’ and the latter ‘referentialists.’ (2)

Or perhaps you have a foot in both camps: a piece of music has its internal order, its sequence of events with its conflicts and resolutions, that it articulates and which the listener may follow; but it also taps into a listener’s previous experience and associated personal meanings ? Meyer declares that they “are not mutually exclusive: that they can and do co-exist in one and the same piece of music.”

Absolutist or referentialist: which one are you ?

—————

1 Stravinsky, I, (1975), An Autobiography, Calder & Boyars: 163

2 Meyer, L (1963), Emotion and Meaning in Music, University of Chicago: 1

Last night, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and David Robertson gave the first performance of Turnage’s new Hammered Out, commisioned for the

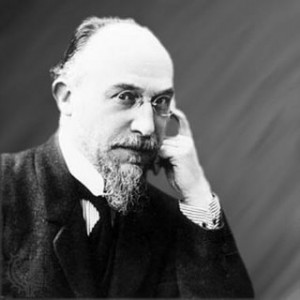

Last night, the BBC Symphony Orchestra and David Robertson gave the first performance of Turnage’s new Hammered Out, commisioned for the  United across centuries: weird composer Erik Satie and Brit pop group Take That. Surely not ?

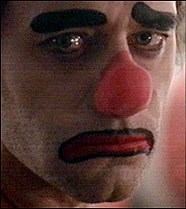

United across centuries: weird composer Erik Satie and Brit pop group Take That. Surely not ? This sense of desperation is also captured to great effect in the video to Take That’s

This sense of desperation is also captured to great effect in the video to Take That’s