Like an aberrant relative of whom one is slightly wary and mistrustful, jazz has always occupied a slightly equivocal place in relation to the classical music tradition. Briefly adored by Les Six and the aspiring avant-garde in early twentieth-century France, it has never quite managed to find itself a comfortable place in the canon of Western classical music.

At the start of the twentieth-century, composers working in France were seized with enthusiasm for the latest craze, jazz, with printed sheet music of works by Scott Joplin and performances by the Paul Whiteman Orchestra fuelling the interests of composers such as Satie and the group, Les Six. Joplin’s opera Treemonisha ,written back in 1910 (although not performed in full realisation until over sixty years later), and Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess from 1935, both show established classical forms embracing jazz: indeed, although famed for pieces such as the ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ and other ragtime piano works, Joplin always referred to his piece as an ‘opera.’

Evidence of the enthusiasm for jazz can be found in the adoption of ragtime music, as in Stravinsky’s Ragtime; or from Satie’s Parade; although, as always with Stravinsky, you get the sense that Stravinsky is playing with jazz as an objective phenomenon, rather than as a visceral, gut-instinct style; he dissects it and plays with it from a distance, somehow, rather than it being the lifeblood of his writing. Antheil’s A Jazz Symphony saw jazz invading orchestral music in 1925.

Jazz harmonies abound in the music of Francis Poulenc. The second movement of Ravel’s Violin Sonata is entitled ‘Blues’ and is evidence of Ravel’s fascination with jazz. Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue opens with the glissando clarinet that immediately speaks of jazz playing; the harmonic palette of the piece is littered with extended jazz chords and copious use of the ‘blue’ note (flattened seventh).

Bad Boy of British contemporary music Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Blood on the Floor sees an improvising jazz trio set amidst a brash, contemporary-sounding ensemble. Turnage acknowledges that jazz and funk are passions of his, and when you listen to Momentum or Your Rockabye, you can hear it.

Artists themselves can be seen to cross the apparently insurmountable classical-jazz divide: André Previn conducts Debussy or improvises with Oscar Peterson; violinist Yehudi Meuhin improvises with Stephan Grapelli;

More recently, former Radio 3 Young Generation Artist Gwilym Simcock is working hard to blur the division between classical and jazz genres. Jazz pianist Julian Joseph collaborated with Harry Christophers’ ‘The Sixteen’ in a programme of Monteverdi for the Spitalfields Festival, up-dating the improvisation expected of keyboard players in the Baroque period for the modern, jazz-infused age. And trumpeter Wynton Marsalis stands astride the classical and jazz genres, moving between both with ease and demonstrating phenomenal technical ability in both fields.

Improvisation has always been at the heart of classical music: from extemporised continuo parts in the Baroque to Mozart’s own improvised cadenzas in the piano concerti, and some elements of spontaneous realisation in the aleatoric music of the 1960s: improvisation belongs with classical music, and isn’t necessarily a separate discipline. Improvisation itself is the very life-blood of jazz, the spontaneous creation of music as a response to the moment of performance, keeping jazz very much alive.

As the twentieth-century turned into the twenty-first, jazz began to establish more of a foothold in classical music, and now it’s sometimes difficult to extricate one from the other in the work of composers such as Louis Andriessen, Turnage, Simcock and others.

Jazz, classical music and improvisation: made for each other.

Stranger than Fiction, by British saxophonist

Stranger than Fiction, by British saxophonist

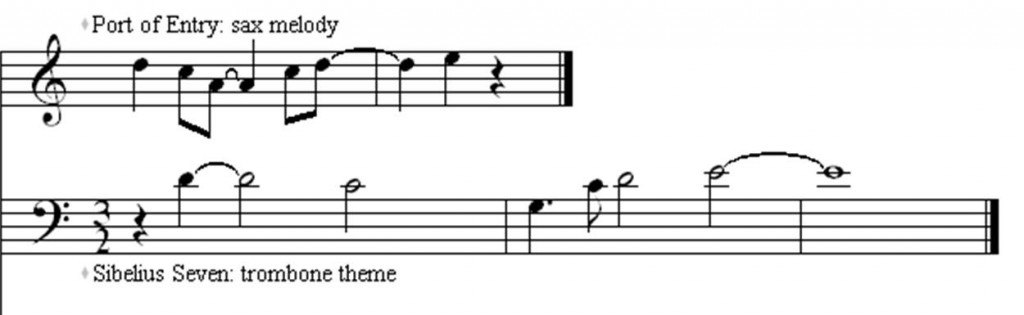

I’ve

I’ve