2023 has been a year of challenges and delights, we’ve amassed new collections, colleagues and knowledge, and – as is tradition – we want to use this post to share some of our highlights with you.

Karen (Special Collections and Archives Manager)

2023 has been another exciting, as well as challenging, year in Special Collections and Archives. We’ve seen a number of changes in our team. In the summer we said goodbye to two members of our team, Rachel who worked with us as a part-time project archivist for the UK Philanthropy Archive and Matt who was our Digital Lead. While in May we welcomed Daniella to the role of Project Archivist – Daniella’s post is externally funded and she is working to make two of our collections accessible and discoverable. If you follow us on our social media channels you’ll already know something of what she gets up to but there is more in her section below. In July we also welcomed Sam to the team. Sam is working on the Laurie Siggs Archive, purchased earlier this year with support from the Arts Council England/V&A Purchase Grant Fund and Friends of National Libraries. The collection includes, original artworks, rough sketches and sketchbooks as well as notebooks and correspondence.

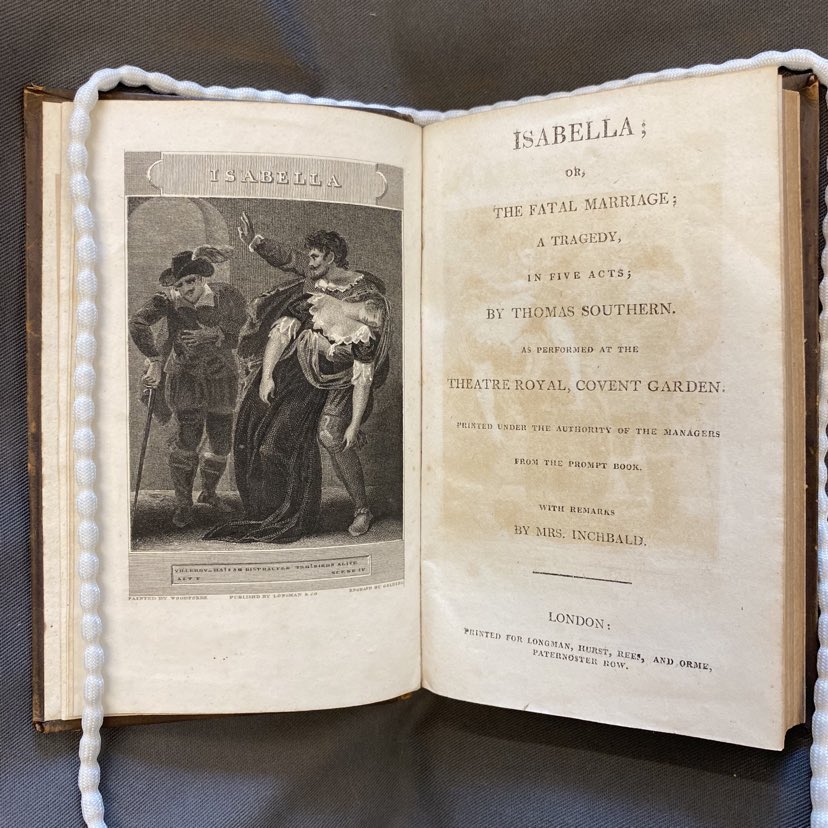

Beth has had an amazingly busy year; working with me on funding applications, completing a survey of artworks around campus as well as all the things she mentions in her piece. One of the highlights for me was the amazing exhibition commemorating 100 years since the publication of T. S. Eliot’s Wasteland. It was a great example of collaborative working with our academic colleagues. It proved to be a great attraction and we had many visitors to the gallery. Beth and I were delighted when Faustin Charles contacted us about his archive. Beth shares more about Faustin below but what you may not know is that he is the author of The Selfish Crocodile – a fantastic book for children. Clair has had great fun working on some of our collections and I know she especially enjoyed working on the Mark Thomas collection. Thanks to her excellent efforts you can now enjoy it too through our online catalogue or by visiting our collections.

Exhibition poster for 100 Years: TS Eliot’s The Waste Land.

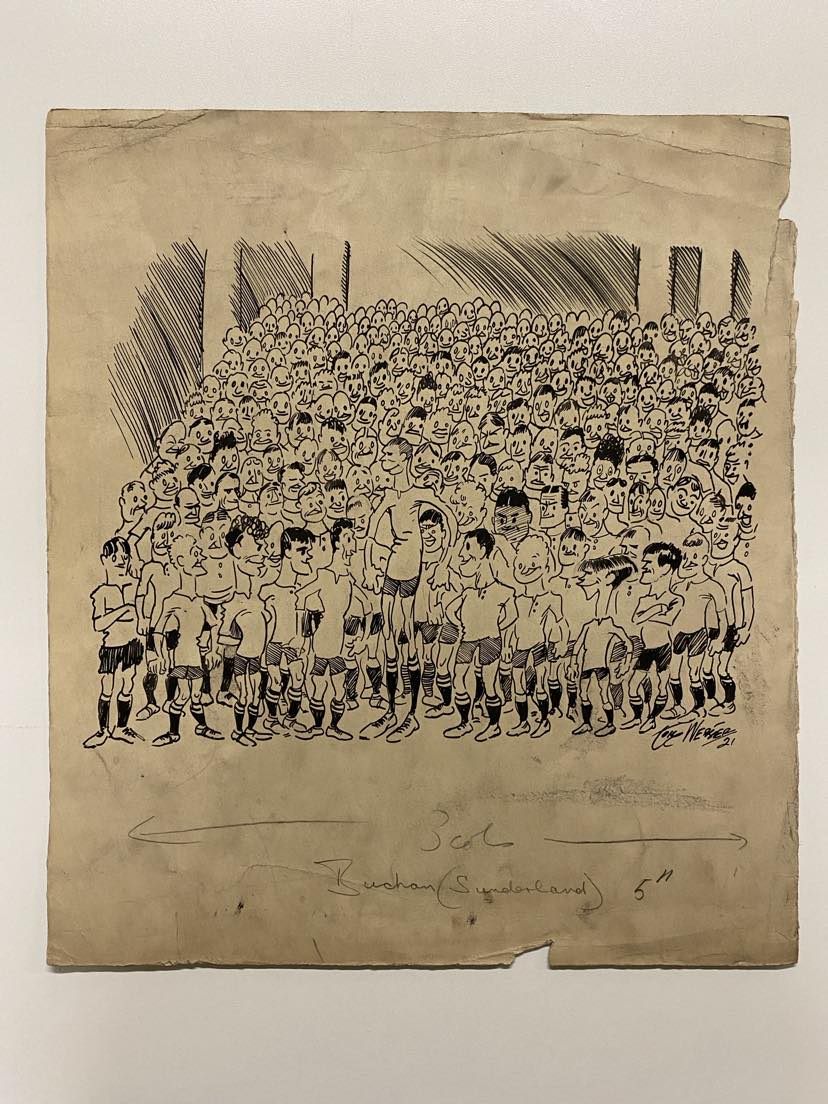

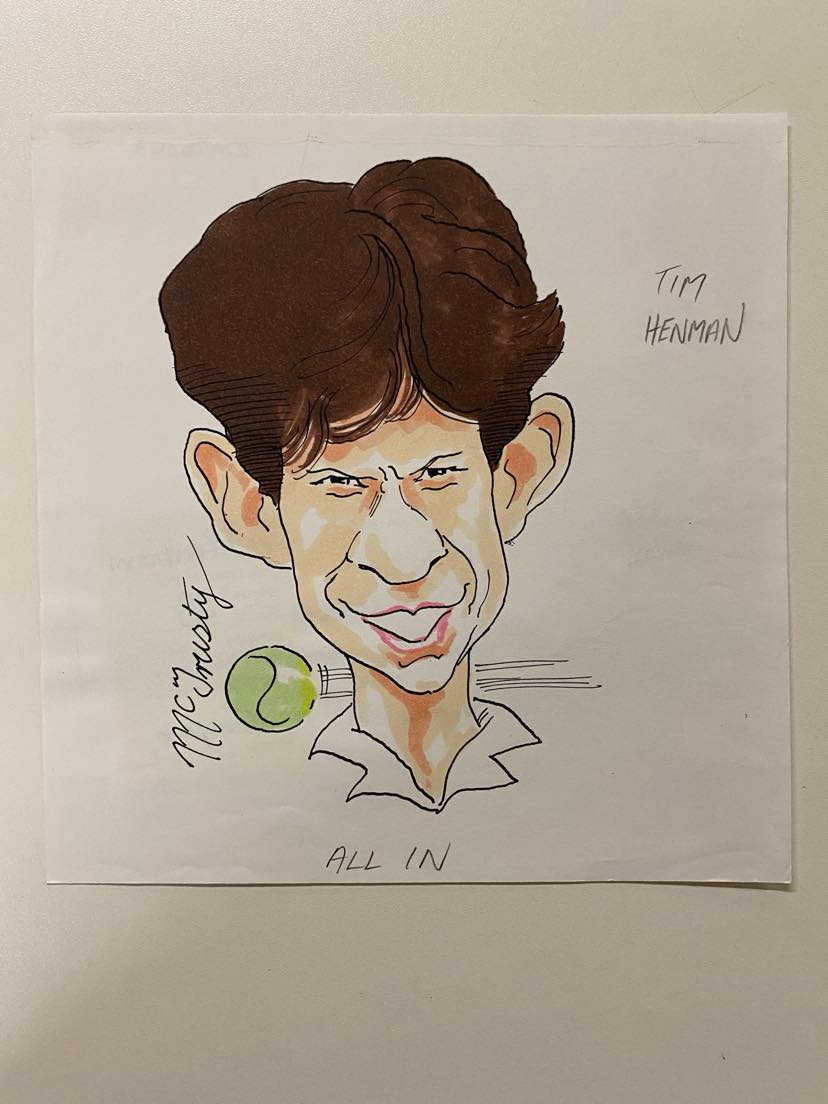

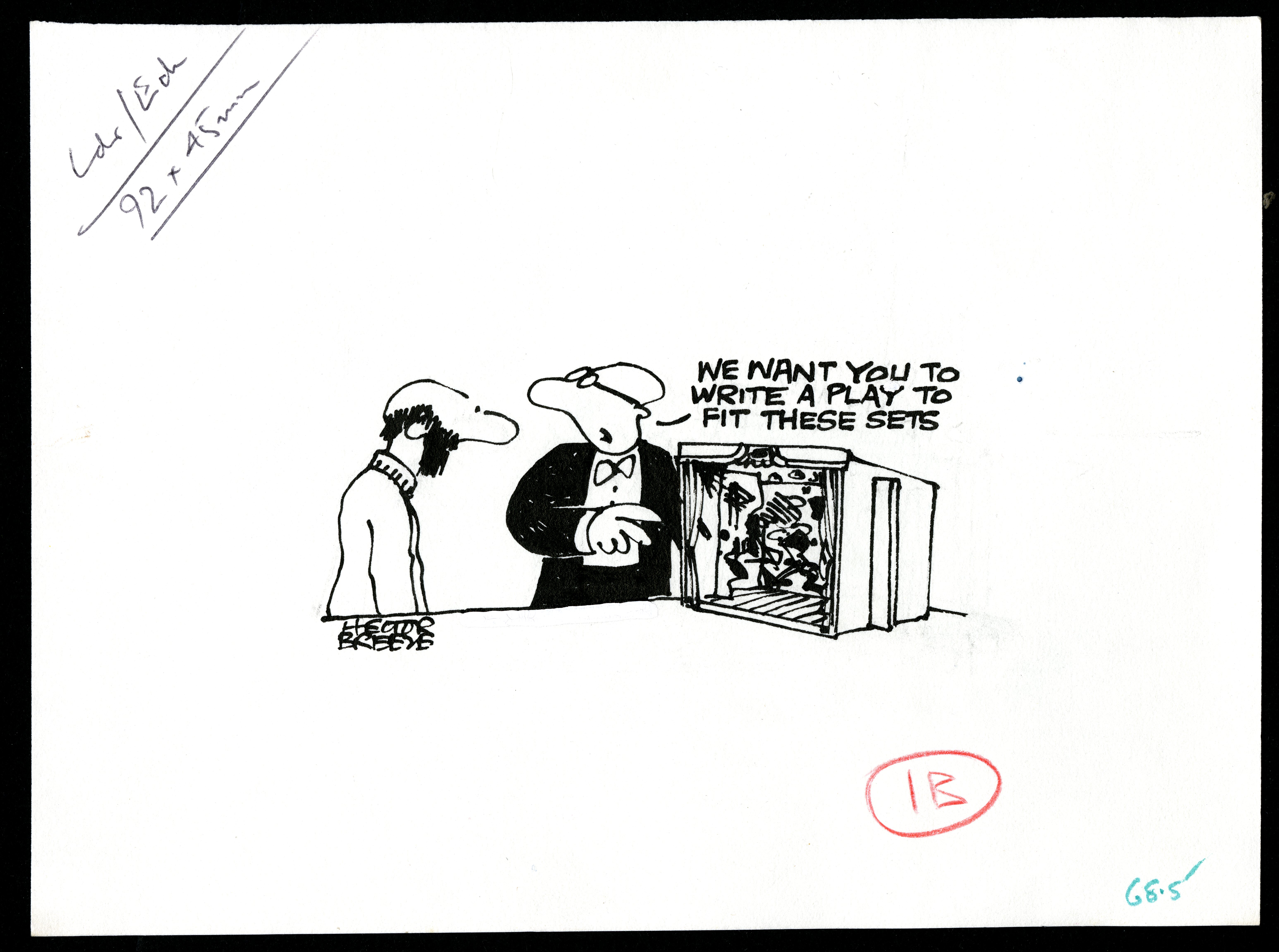

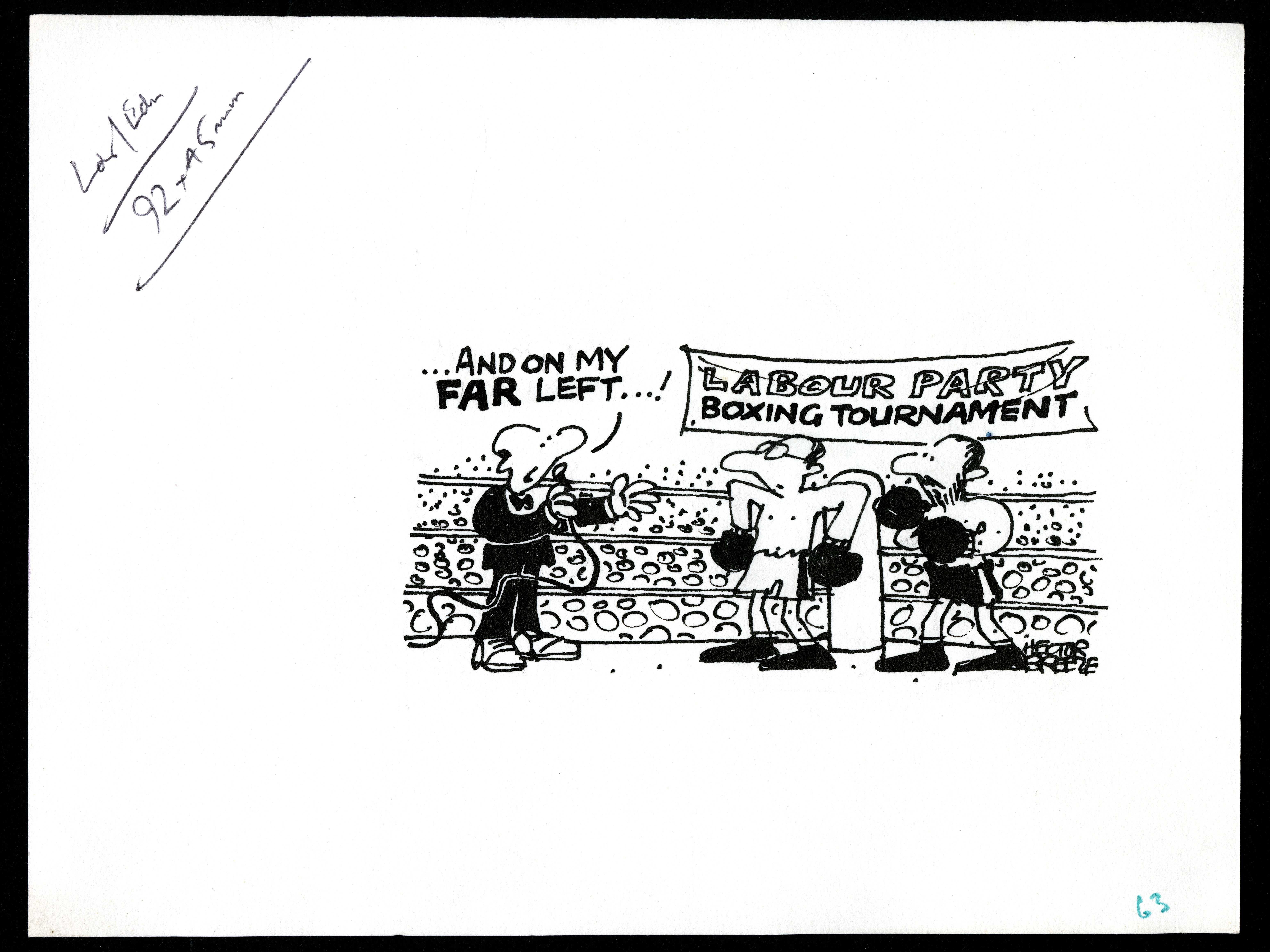

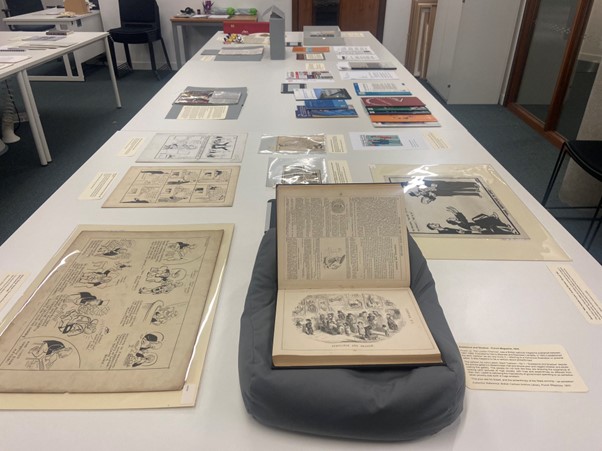

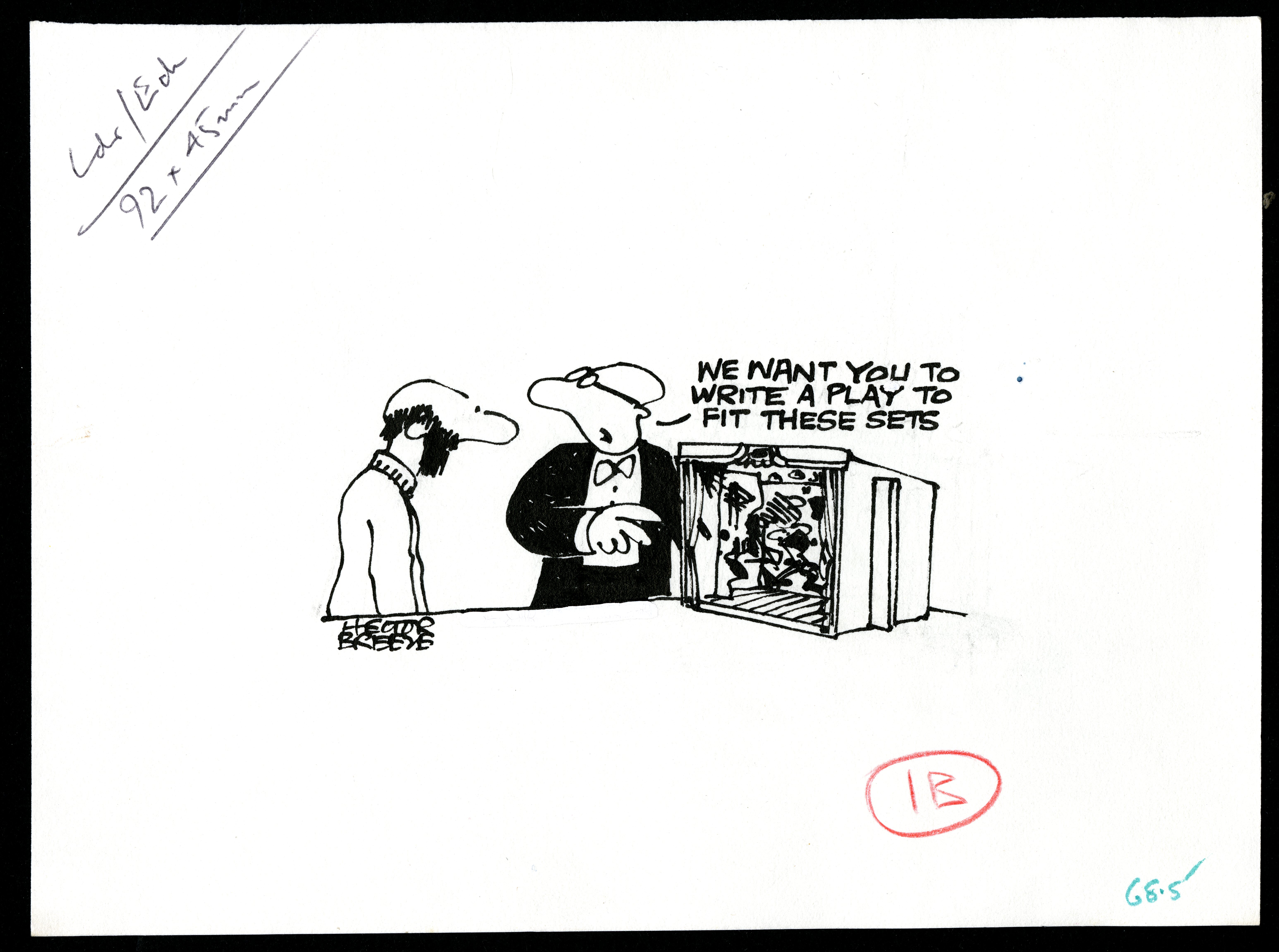

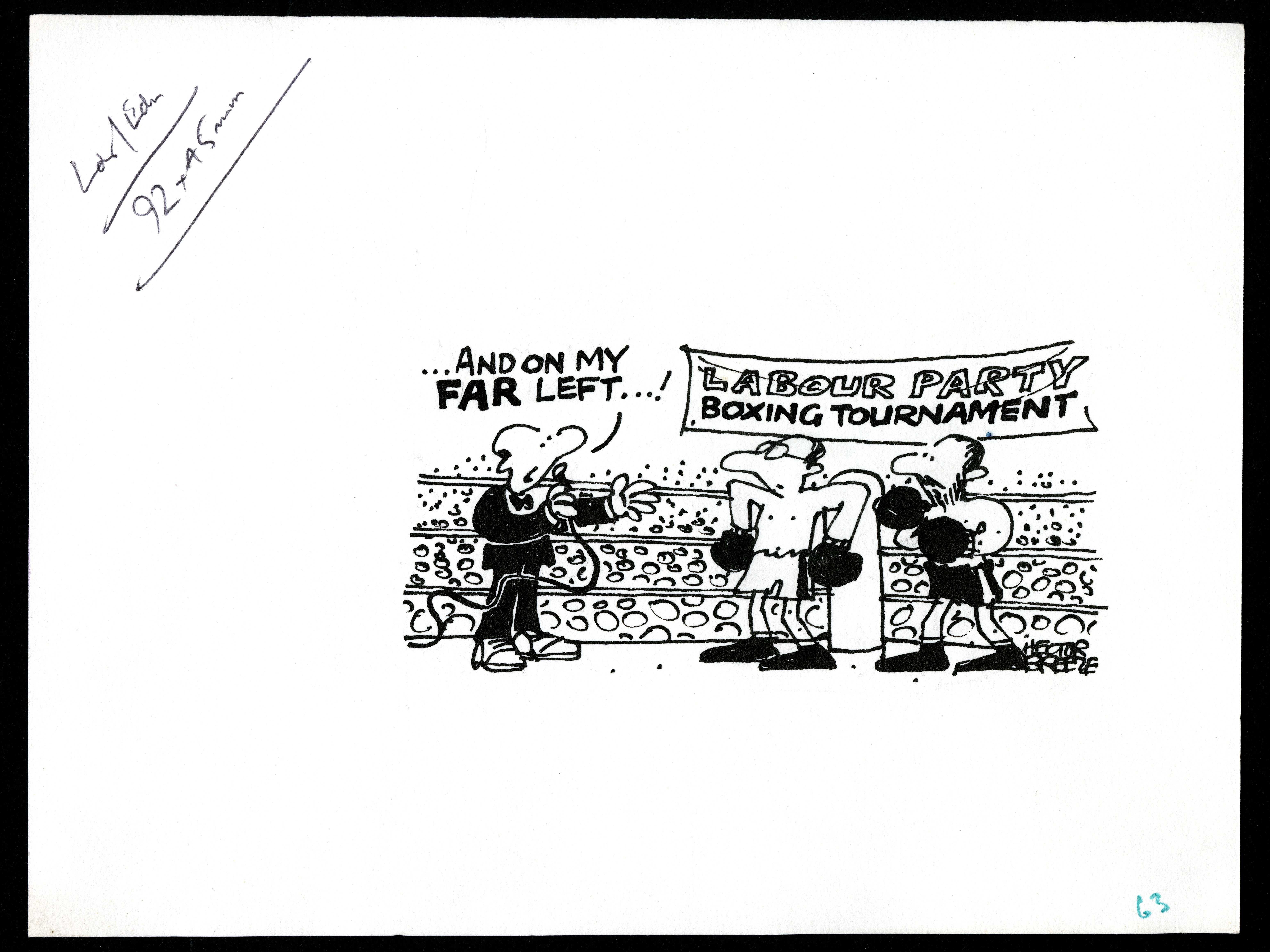

Christine has gone from strength to strength in developing her skills and talents as our Coordinator. She has finished cataloguing her first book collection, of which you can learn more about below and the Childrens Book Collection has so many lovely books for us all to enjoy. Christine also helped to develop the sessions for Discovery Planet in Ramsgate, working with our academic colleague Stella, and our whole team. I hope we can do more to these amazing sessions in the coming year. Mandy continues to beaver away making sure our cuttings collection is kept up to date. At the same time she has been working on digitising the original art works of Hector Breeze. Hector’s cartoons were published in Private Eye, Punch, Evening Standard, and other popular Daily newspapers. Jacqueline completed cataloguing the Carl Giles books, and moved on to catalogue Arnold Rood’s collection (he had a very attractive bookplate) and Jack Reading and Colin Rayner’s collection. Jacqueline has uncovered some real treasures, which I’ve enjoyed seeing. We’re looking forward to seeing what she uncovers next year! Our colleagues Stu and Matthias have been working with us one day per week and have made great progress in dealing with our British Cartoon Library backlog as well as our Shirley Toulson Poetry Collection, making them available to everyone.

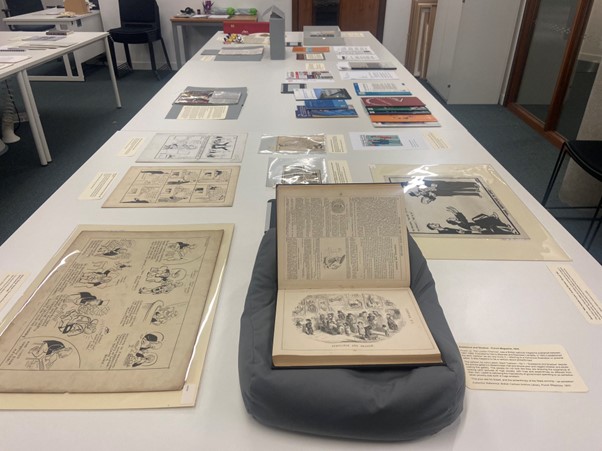

Display of Special Collections and Archives materials at Discovery Planet, Ramsgate.

Our volunteer projects this year have been hugely successful, and we continue to be amazed by the talented people that come to support us in our work.

Looking forwards to 2024, we have some recently acquired collections that will be announced very soon. One I can mention though is a beautiful collection of Caribbean literature, donated by one of our former academics. We plan to start work on this collection in 2024 alongside some work to process a collection of African literature including works in the African Writers Series. Keep an eye on our social media channels for updates. And if you are not already following us do have a look at the Special Collections and Archives Advent Calendar – it’s on X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram @UniKentArchives.

Beth (University Archivist)

2023 has been full of highlights and it is hard to pick out a few special things to represent such a busy year!

With the University Archive collections this year I focussed on the archives of the Colleges. At the beginning of the year I started a huge (and still ongoing) project to sort and catalogue the enormous Eliot College archive. This has now been un-boxed and arranged in a logical way, and cataloguing is on-going. This is a huge step forward in preserving the history of these important institutions within the University, and there are many fascinating records coming out of this.

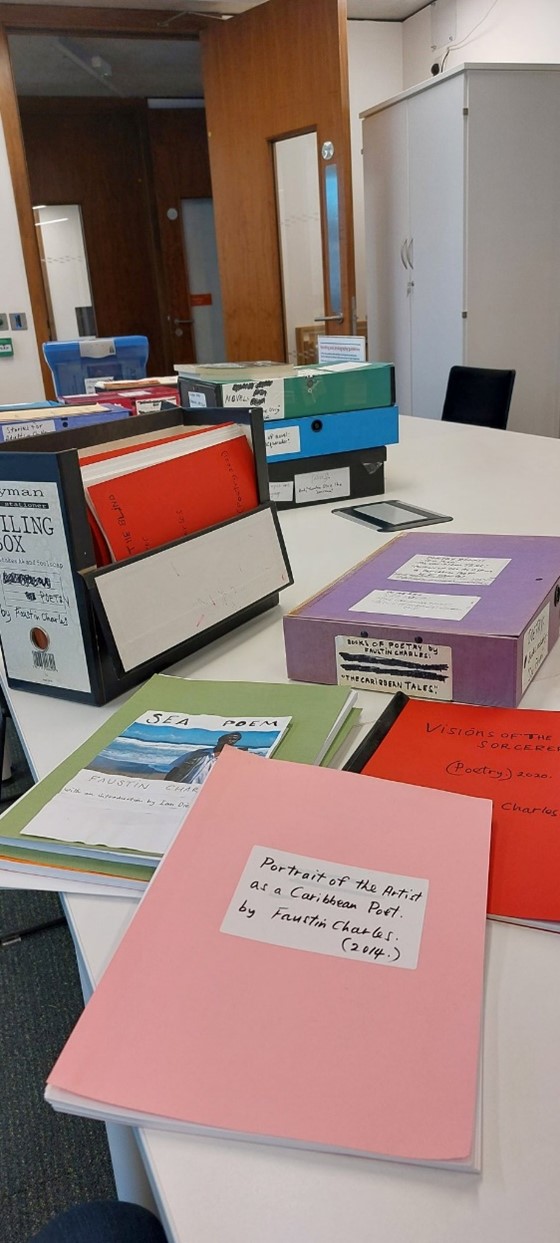

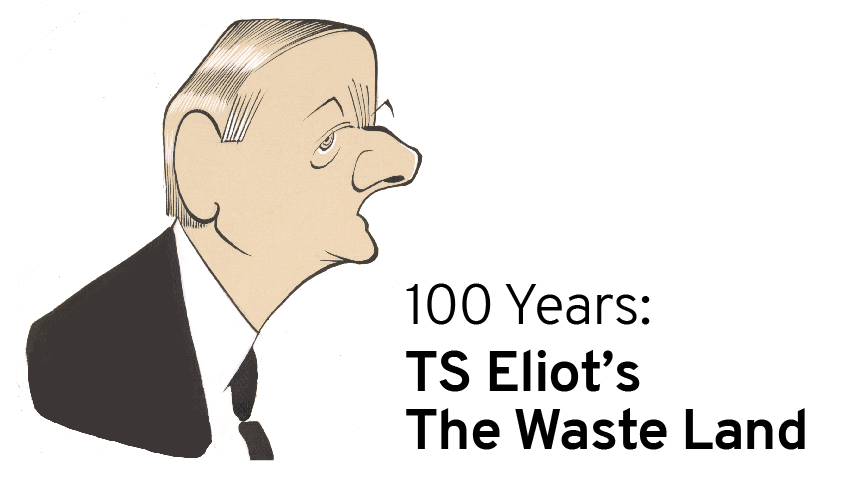

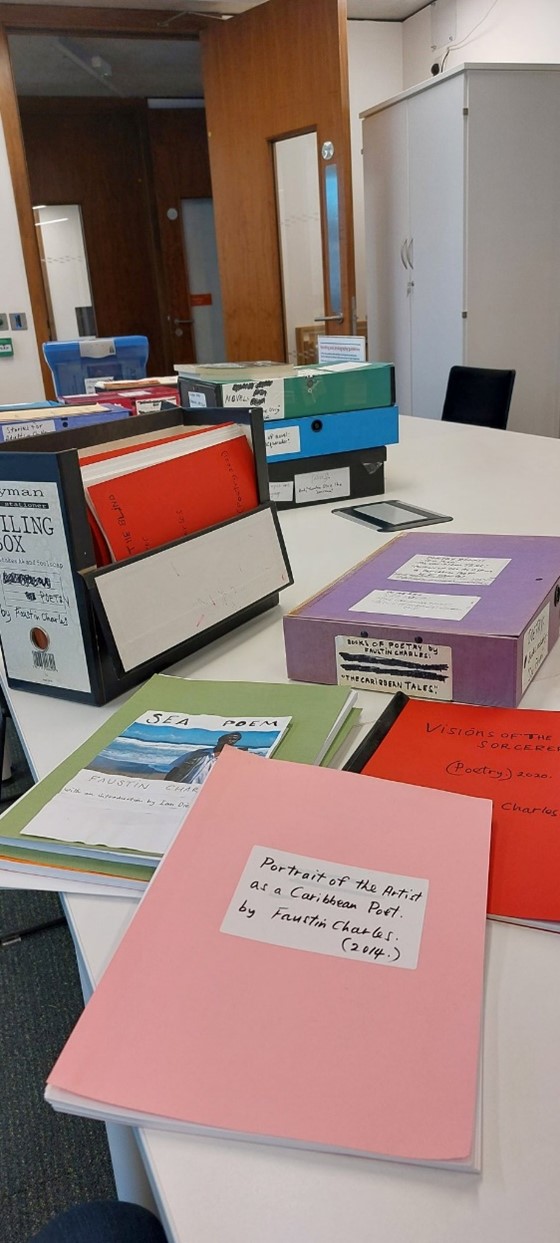

We also received a brilliant collection of literary manuscripts from alumnus Faustin Charles, a storyteller and poet, originally from Trinidad and who studied at the University of Kent from 1977-1981. Faustin is an important voice in Caribbean poetry and storytelling, and his collection of manuscripts and correspondence will provide a fascinating insight into his work.

The archive collection of Faustin Charles, Caribbean storyteller and poet, being catalogued at the University of Kent Special Collections and Archives.

With the UK Philanthropy Archive collections we have continued to build and expand this growing collection receiving a new collection from the Hilden Charitable Trust in the last few weeks! We have been involved with two great events to showcase the wider philanthropy collections and begin to share information about the content and its importance for research. In April we held a mini-display of material at the Understanding Philanthropy conference, and then later in November we helped organise the 15th Anniversary Colloquium for the Centre for Philanthropy, Philanthropy: Past, Present and Future, which included our 3rd annual Shirley Lecture. This year we were delighted to welcome Orlando Fraser KC, the Chair of Charity Commission of England and Wales, who delivered an interesting lecture of the role of philanthropy in the charity sector. We were able to showcase the UK Philanthropy Archive collections at this event, giving tours of the collections talking to participants about their value for research.

Display of philanthropy related items for the Centre for Philanthropy’s 15th Anniversary Colloquium in November 2023.

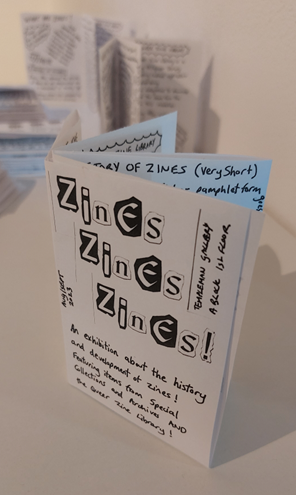

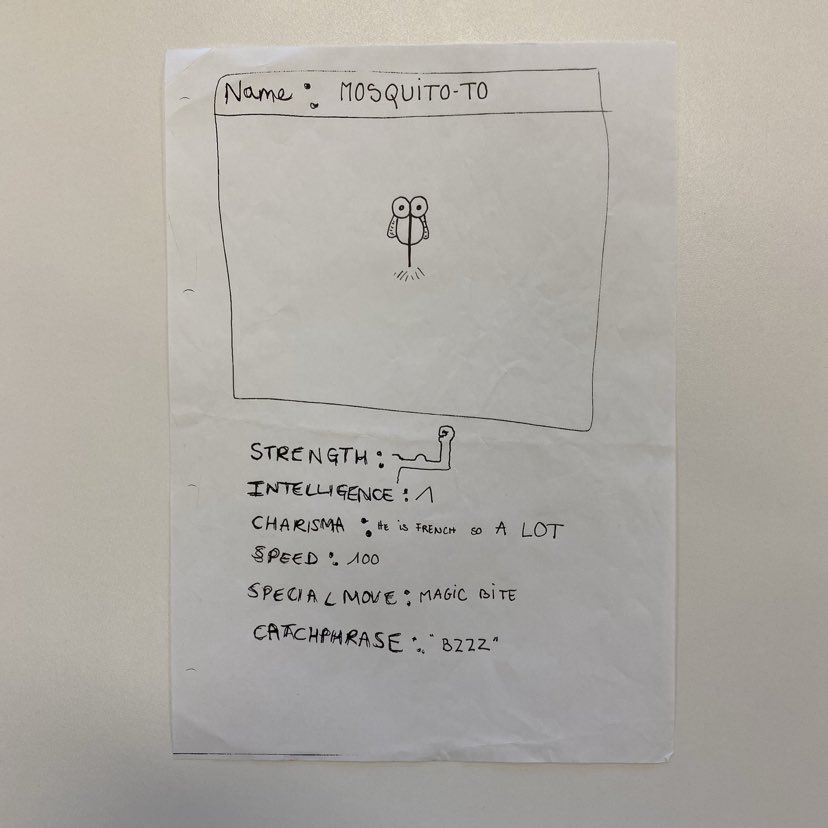

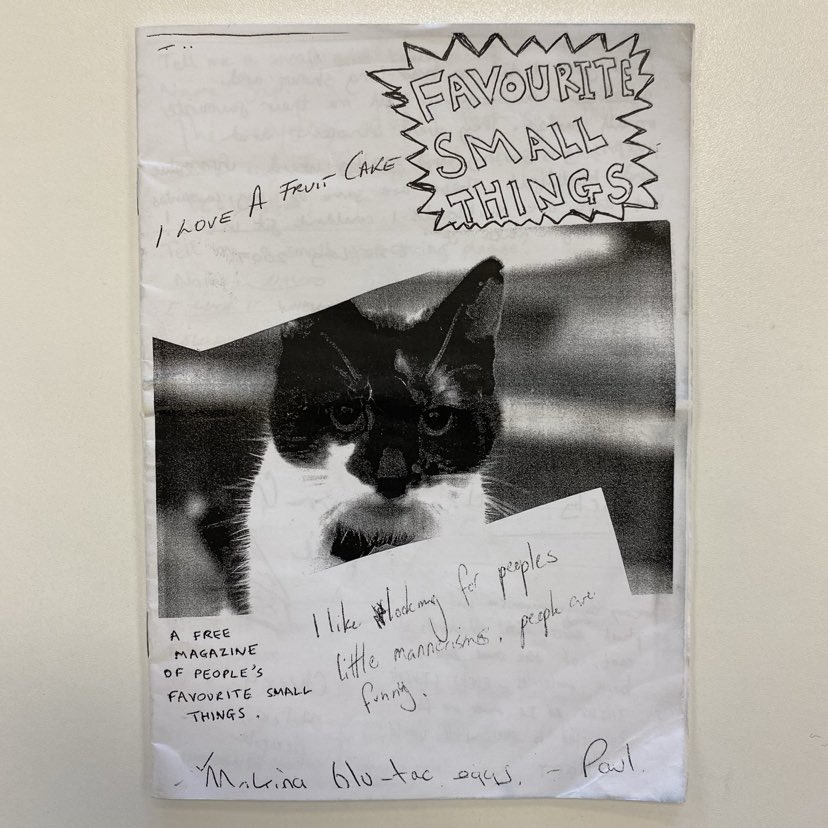

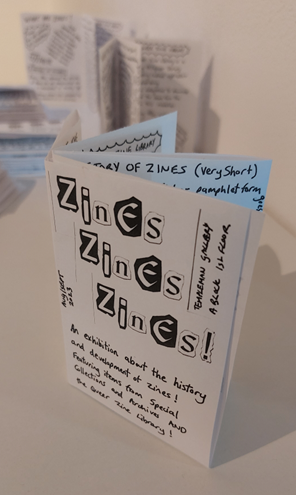

Our exhibition schedule has been jam packed this year beginning with the 100 Years: TS Eliot’s The Wasteland which was on until April, after which we installed the Migrating Materia Medica exhibition in collaboration with colleagues in the Schools of English. In August we added a fabulous short term exhibition on zines and zine making, called “Zines Zines Zines!” which explored the history of this popular genre of self-publishing and allowed us to display some of our zine collections, modern poetry and artist books, and also a loaned collection of zines from the Queer Zine Library.

The zine we made to support the Zines Zines Zines exhibition this year.

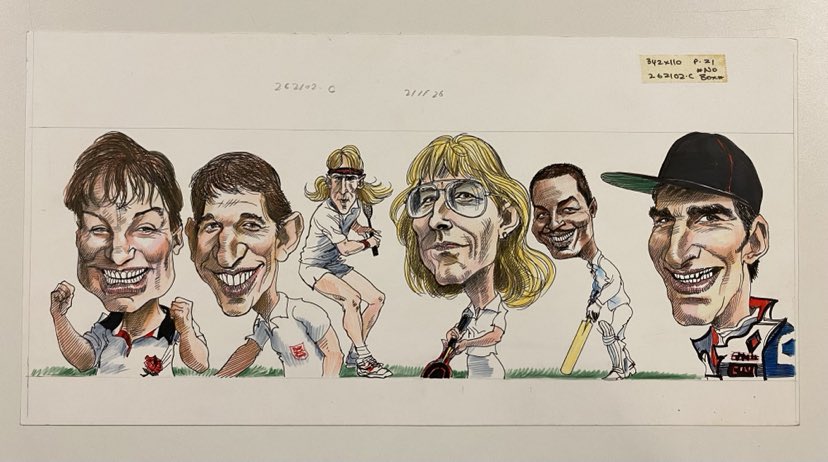

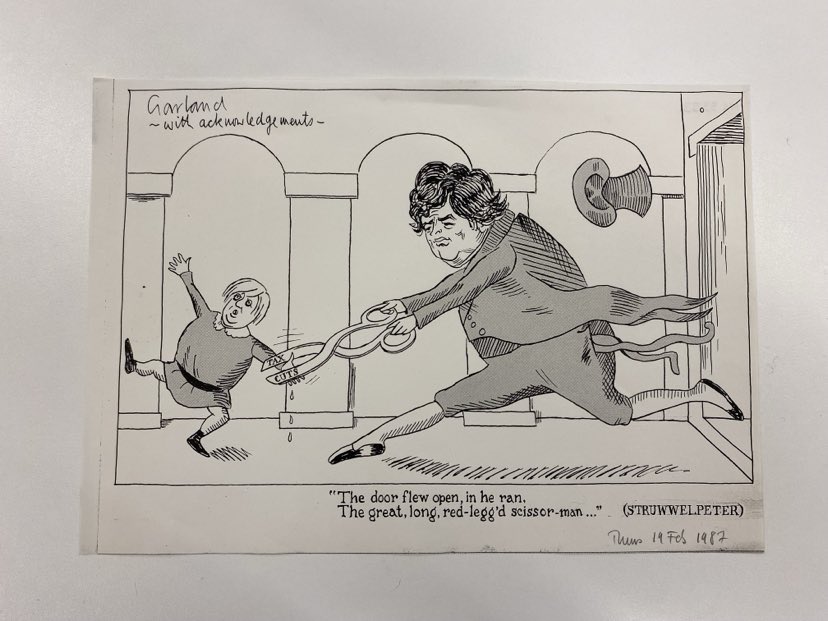

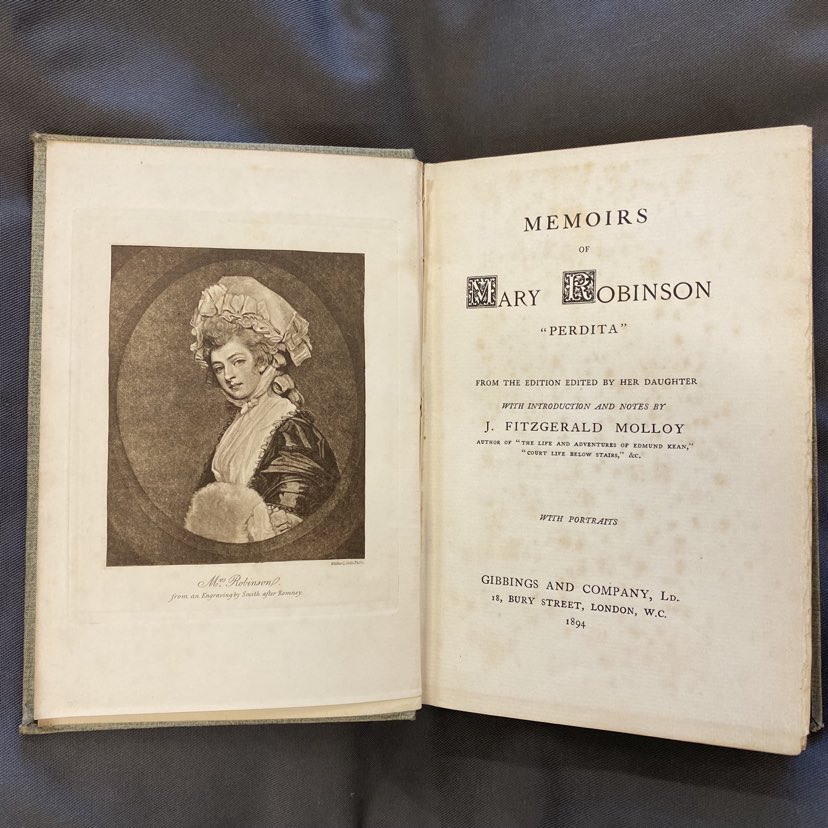

We have ended the year by installing our new exhibition – which has been curated by a fab team of volunteers to kick off our celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the British Cartoon Archive at the University. The first cartoons arrived at Kent in 1973 and the Centre for the Study of Cartoons and Caricature opened in 1975 – which later developed into the British Cartoon Archive. Between 2023 and 2025 we are running a programme of events and activities to mark this significant anniversary. The 50/50 Project, where our volunteers have selected 50 cartoons reflecting the 50 years of the British Cartoon Archive, was the first of our celebratory activities and was launched in October. The exhibition will be on display until the end of February so do come along and see it if you can.

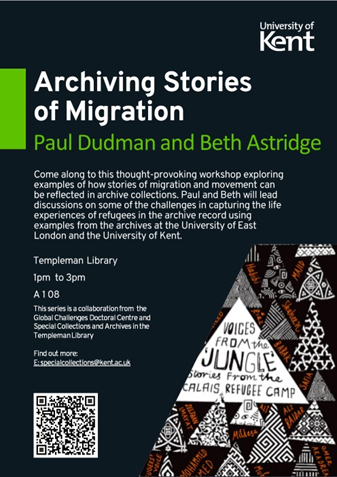

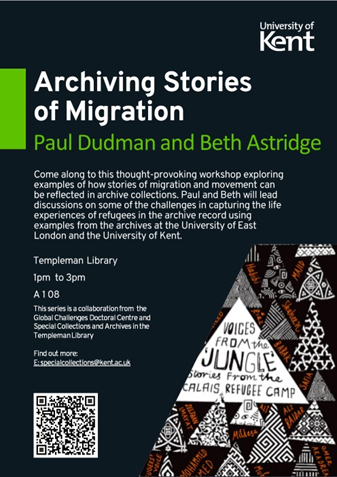

In addition to all of this – a particular highlight for me this year was in organising and delivering our Telling Our Tales series of workshops, held in June, in the run up to Refugee Week. This series of creative workshops related to our project and exhibition in 2022, Reflections on the Great British Fish and Chips. The workshops explored the ways in which we tell, share and preserve stories of migration and movement. Working alongside our amazing colleague Basma El Doukhi, we invited speakers to run artist-led workshops where participants learned about sharing migration stories and how these can be expressed and recorded through portraiture and photography. We held an In Conversation event between Basma and Rania Saadalah, a Palestinian Refugee, who shared her photography work where she lives in the refugee camps in Lebanon. Our final workshop was with Paul Dudman from the Living Refugee Archive at the University of East London, who talked about how to preserve stories of migration and the lived experiences of migrants living in Britain.

The workshops were all thoughtful and impactful events, that encouraged us to challenge stereotypes, build better relationships with people in our communities, and foster a spirit of understanding and compassion for others. This sentiment seems particularly important to highlight at this time of devastation and suffering in the ongoing war between the Israeli and Palestinian people. It remains vital that the stories and experiences of refugees and those with lived experience of migration are heard, shared and preserved to ensure their voices do not go unrecorded.

Poster for one of the Telling our Tales workshops, held by Paul Dudman and Beth Astridge.

Clair (Digital Archivist)

Once again, it’s been an incredibly busy year for Special Collections and Archives, and if you can excuse the cliché, it has really flown by! There’s been lots of enjoyable projects along the way, but I’ve chosen just three to talk about in this year’s round-up.

Firstly, we’ve had a bumper year for volunteering! Volunteers bring so much to our service, and help us achieve more than we could ever do alone with our small team. We’ve had the pleasure of working with over 20 individual volunteers this year on various tasks and projects. In particular, we’ve run two volunteer projects related to the British Cartoon Archive (BCA) this year. The first was the 50/50 project where volunteers were asked to research, select and curate an exhibition of 50 items from the BCA to celebrate 50 years since the founding of the collection. The second was the Cartooning Covid-19 project, where volunteers supported us in making over 400 cartoons published during the Covid-19 pandemic available to the public via our catalogue. It’s been such a pleasure working with all of our fantastic volunteers this year, and we hope to continue to work with some of them again in the next.

Our 50/50 volunteers.

In terms of cataloguing, I had a blast sorting and cataloguing material from our Mark Thomas Collection in the British Stand-Up Comedy Archive (BSUCA) this year. The Mark Thomas Collection has been part of BSUCA since its very beginnings, with the earliest set of records being deposited in 2013, and we were delighted to receive an accrual to his collection in 2020/21. This new batch of records contained notebooks, publicity, audiovisual material, and material related to his radio and TV work. In addition to this cataloguing, I also had the help of two work experience students in sorting and cataloguing the significant ‘100 Acts of Minor Dissent’ series. Records can be viewed on our catalogue now: https://archive.kent.ac.uk/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=BSUCA%2fMT

100 Acts of Minor Dissent: Act 61-63 – the BASTARDTRADE logo (designed by Greg Matthews) is trade marked and was created as a symbol of bad corporate behaviour (BSUCA/MT/3/8/26).

Finally, in the first half of this year I was lucky enough to take part in the National Archives’ peer mentoring scheme. I really enjoyed the experience of being a mentee and benefited from having a very knowledgeable, kind and supportive mentor. The scheme was the perfect opportunity for me to take the leap in creating a Digital Asset Register for our digital collections. Having a Digital Asset Register in place is important as it enables us to have control over our digital objects (both born-digital and digitised) and helps keep us informed of the file formats we hold so that we can make decisions about any preservation actions we may wish to take. It’s a huge step forward in improving our digital preservation maturity, so that’s definitely something to celebrate!

Computer Laboratory, Nov 1977 (UKA/PHO/1/1014)

Daniella (Project Archivist)

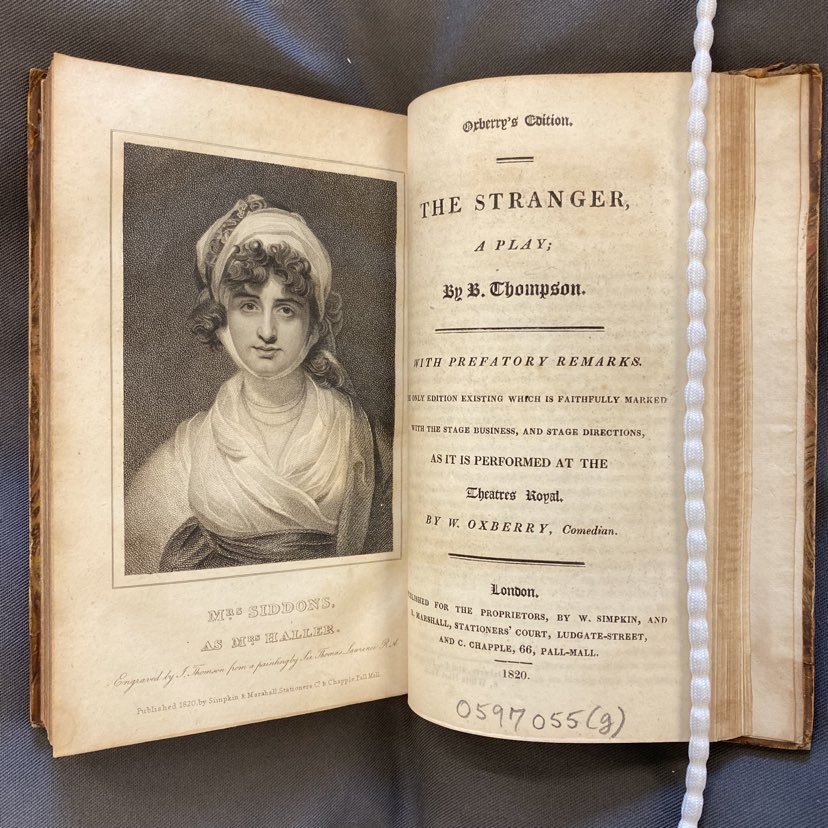

2023 has been an exciting year for me as I joined Special Collections & Archives as a Project Archivist, working on two cataloguing projects – Craigmyle Consultants UK Ltd’s archive and the “Oh Yes It Is!”: Cataloguing the David Drummond Pantomime Collection project, funded by Archives Revealed a partnership programme between The National Archives, The Pilgrim Trust and the Wolfson Foundation.

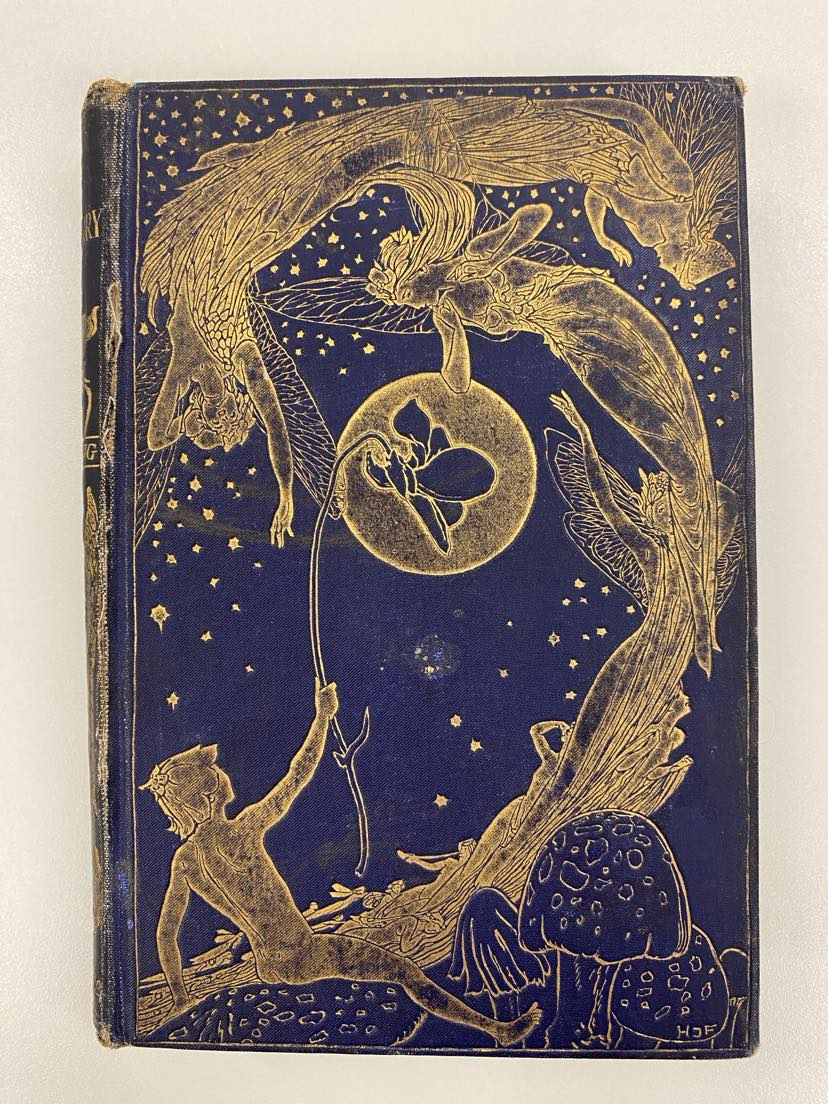

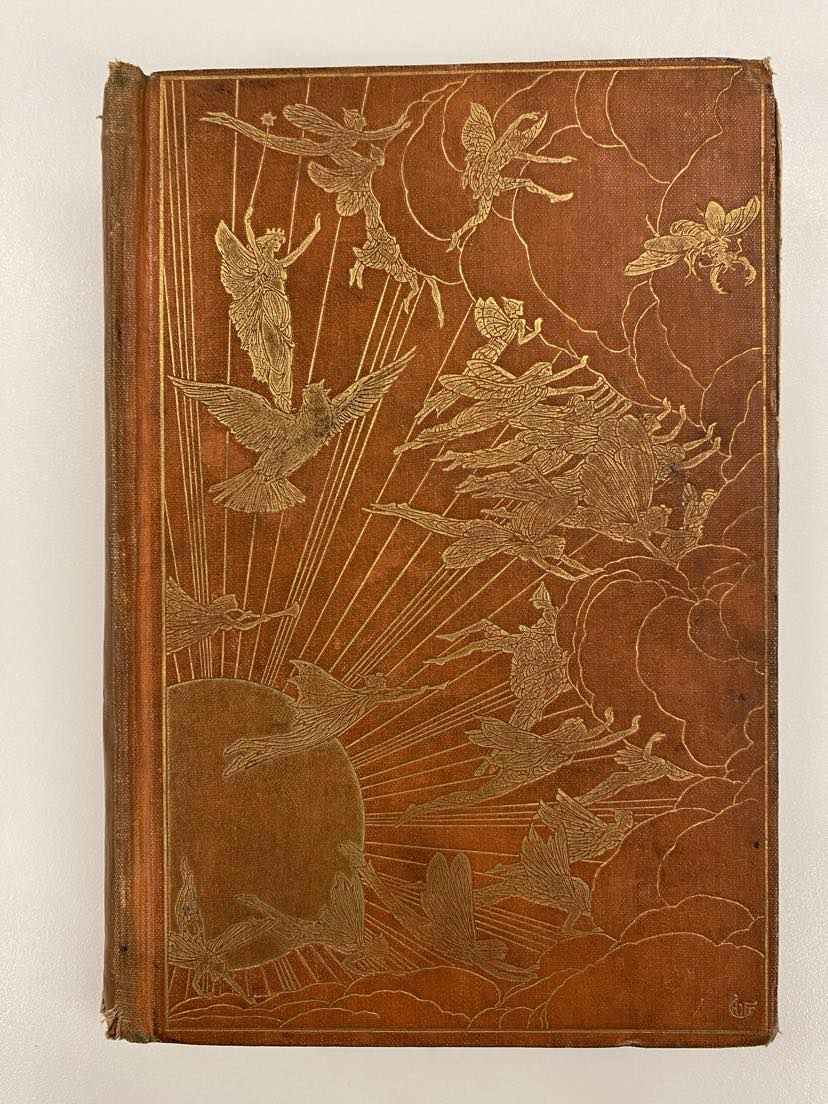

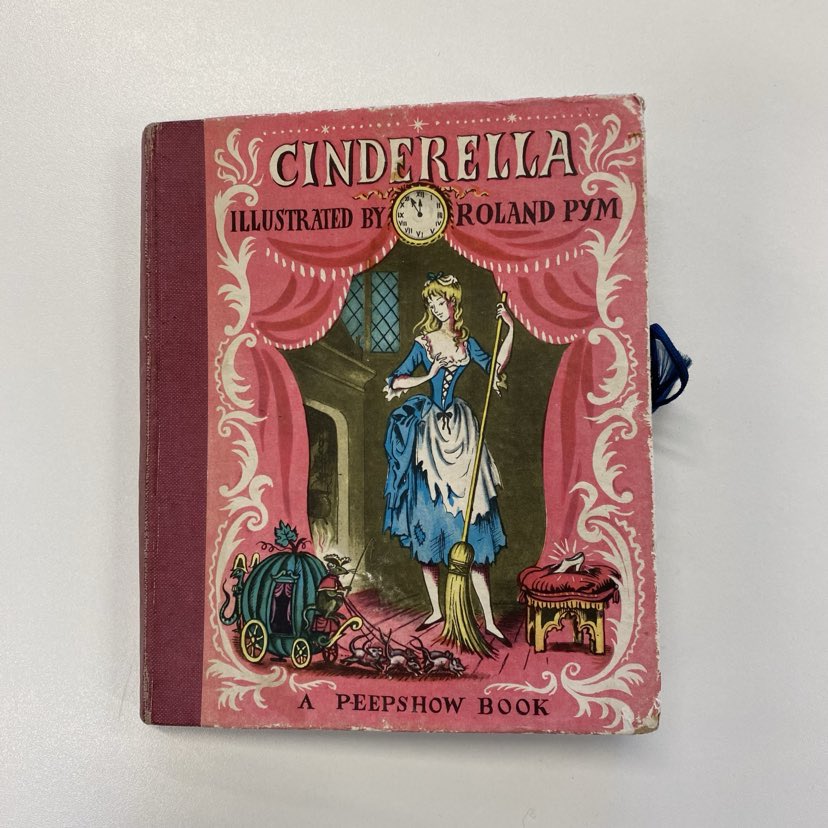

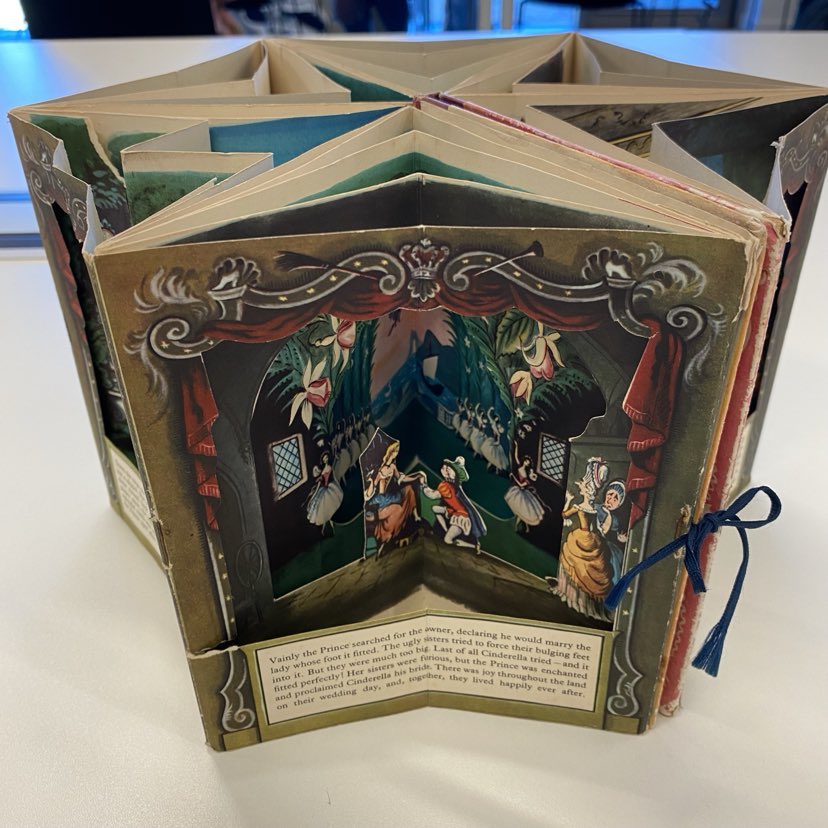

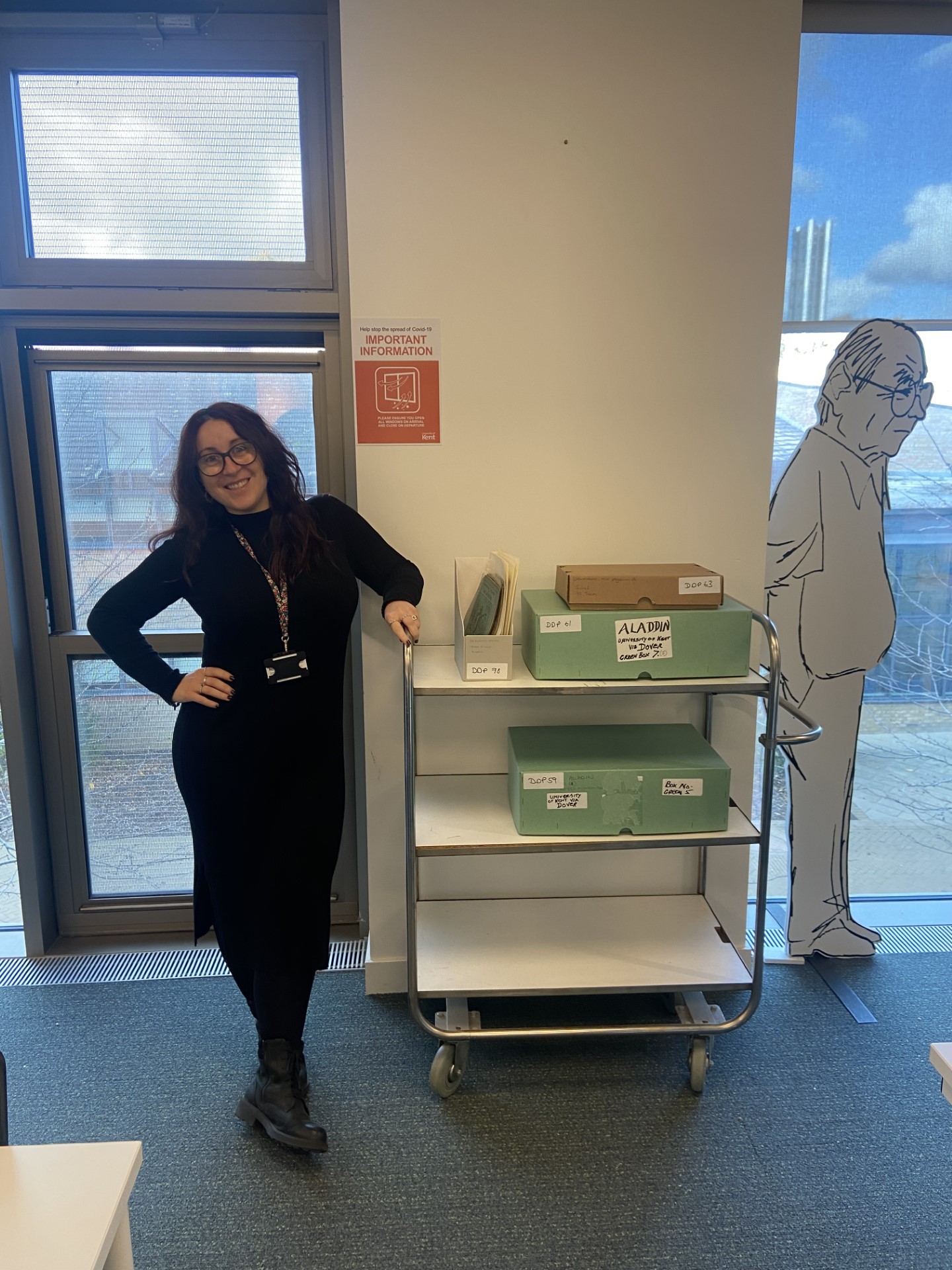

Donated by the collector David Drummond, the collection contains materials relating to a range of pantomimes, such as Cinderella, Puss in Boots, and Sleeping Beauty, as well as ephemera and photographic materials showcasing Principal Boys and Principal Dames. There are also gorgeous costume designers by prolific costumer designers, such as Wilhelm and Archibald Chasemore. Positive steps have been made with the cataloguing and, so far, I have catalogued in draft materials relating to Florrie Forde, Albert Chevalier, Godfrey Tearle, and David Wood. My latest cataloguing work package has focused on items relating to the pantomime Aladdin, started to coincide with this year’s pantomime performance at the Marlowe Theatre in Canterbury. Watch this space to see these be added to our catalogue! Fantastic work is also being done by a wonderful group of volunteers who sorted and have been listing programmes and flyers for the pantomime Cinderella – they have made amazing progress and we can’t wait to share this with researchers.

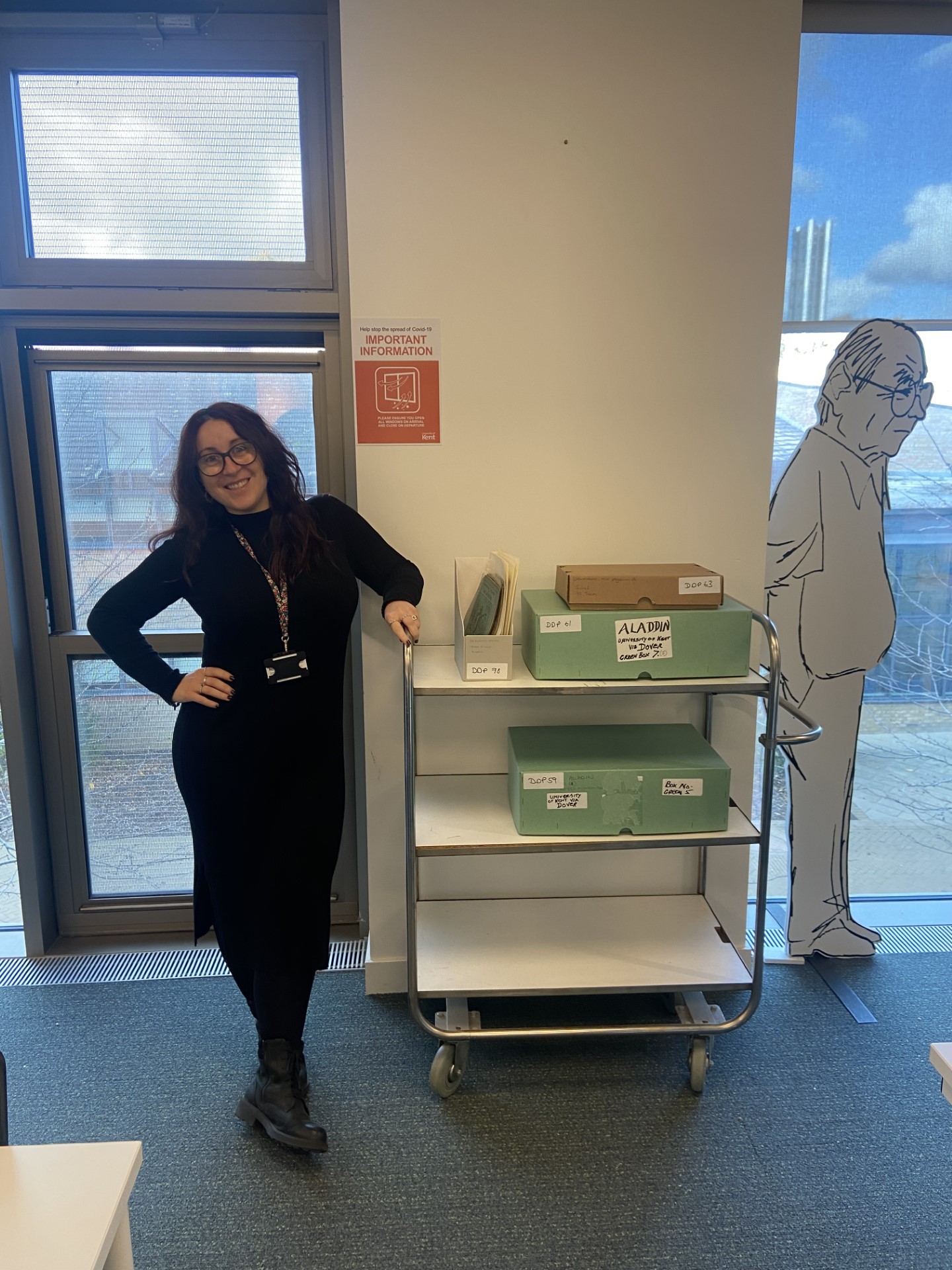

Aladdin materials in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection.

Linked to the above, an absolute highlight of working on the David Drummond Pantomime Collection was going to the local pantomime at the Marlowe Theatre to watch Aladdin with my colleagues. We had an absolute blast watching the Dame strut her stuff whilst dodging the oncoming water guns!

Craigmyle’s archive is very different to the David Drummond Pantomime Collection and provides a different perspective to fundraising. It is interesting because the collection shows how this organisation, which was set up in 1959, helped charities across the United Kingdom fundraise. They work with a variety of clients ranging from Cancer Relief Macmillan to cathedrals and parish churches. Schools and education fundraising is of particular importance to Craigmyle. In fact, the company’s earliest focus was on this sector, with initial clients including The King’s School Ely, Tonbridge School, St John’s College Durham and Wycombe School. The project is well underway, and I have scoped what there is and begun to appraise and weed to select what we will be keeping for permanent preservation.

Working on Craigmyle’s archive has also given me the chance to meet staff in the Centre for Philanthropy, and Beth and I had the exciting opportunity to work with Professor Beth Breeze and Dr Karl Wilding to organise the Philanthropy Past, Present and Future colloquium. We had over 80 people register and attend, and has fantastic talks from Michael Seberich and Orlando Fraser, Chair of the Charity Commission for England and Wales. It was also a great chance to get the Craigmyle collection out and engage participants with what research can be done with this archive.

We’ve had an exciting end to the year by appointing two Archive Assistants, Cassie and Farradeh, who have joined me on the project to catalogue Craigmyle’s archive. We’re thrilled for Cassie and Farradeh to be a part of the team and they are sorting, listing, and repackaging appeal literature that forms a part of this collection. They have made an amazing start and have the following to say about their experience on this project so far:

Cassie: “I’ve only been working on the project for a couple of weeks so far but I already feel like I’ve learned so many new things about working in archives, and about the philanthropy sector. It’s been fascinating working through the new Craigmyle collection and I can’t wait to see what else we find and discover the ways in which this material can contribute to the UK Philanthropy Archive”.

Farradeh: “It’s really exciting to see what goes on behind the scenes at an archive, and have an active part in the formation of a new collection. It has made me see archives in a different light, understanding the thought and care archivists put into their craft, and appreciating the level of nuance that goes into executive decisions”.

Cassie and Farraday working on the Craigmyle Archive.

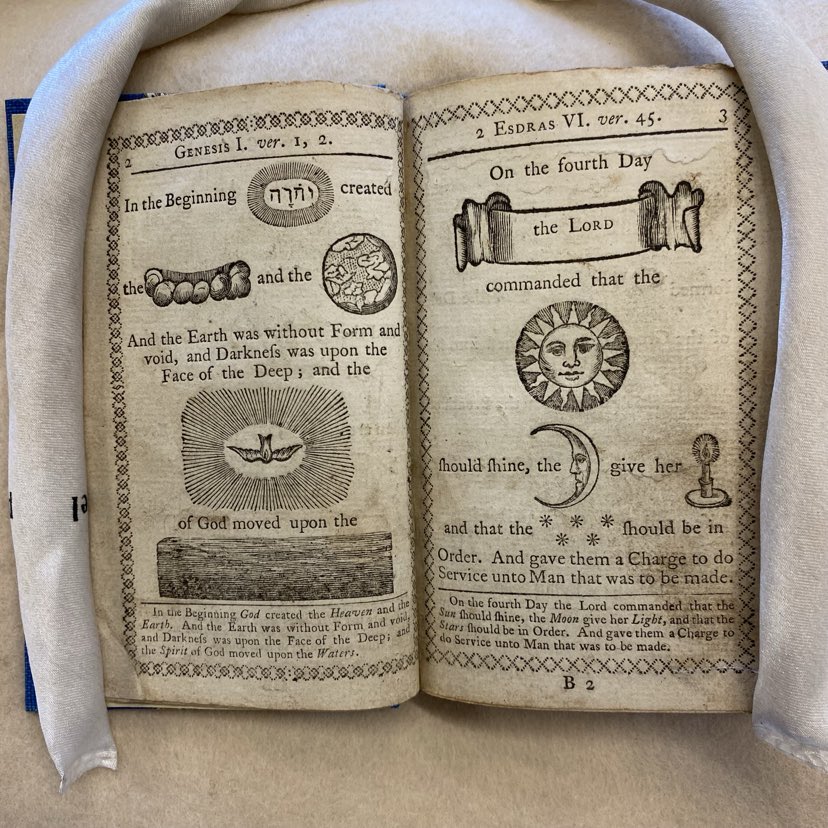

Outside of my collections work, Karen and I contributed to Dr Suzanna Ivanic’s module The Early Modern World: Conflict & Culture, 1450-1750. I gave a lecture about the recordkeeping revolution and archives between the sixteenth century and mid-eighteenth century. I also supported Karen and Christine in delivering the seminars for this module, during which students were able to examine and handle some of the spectacular early modern printed texts in the collection, including editions of William Lambarde’s Perambulation of Kent, William Somner’s Antiquities of Canterbury, and indentures ranging from the reigns of Henry VI to Elizabeth I that are found within the Ronald Baldwin collection.

Christine (Special Collections and Archives Coordinator)

This has been my first full year working as the Special Collections and Archives Coordinator, and it’s been a real opportunity to increase my knowledge of our collections and support a variety of digital and in person engagement activity – in the Autumn term alone, we engaged 177 UG and PG students through seminars, not to mention individual readers, school groups and prospective open day students.

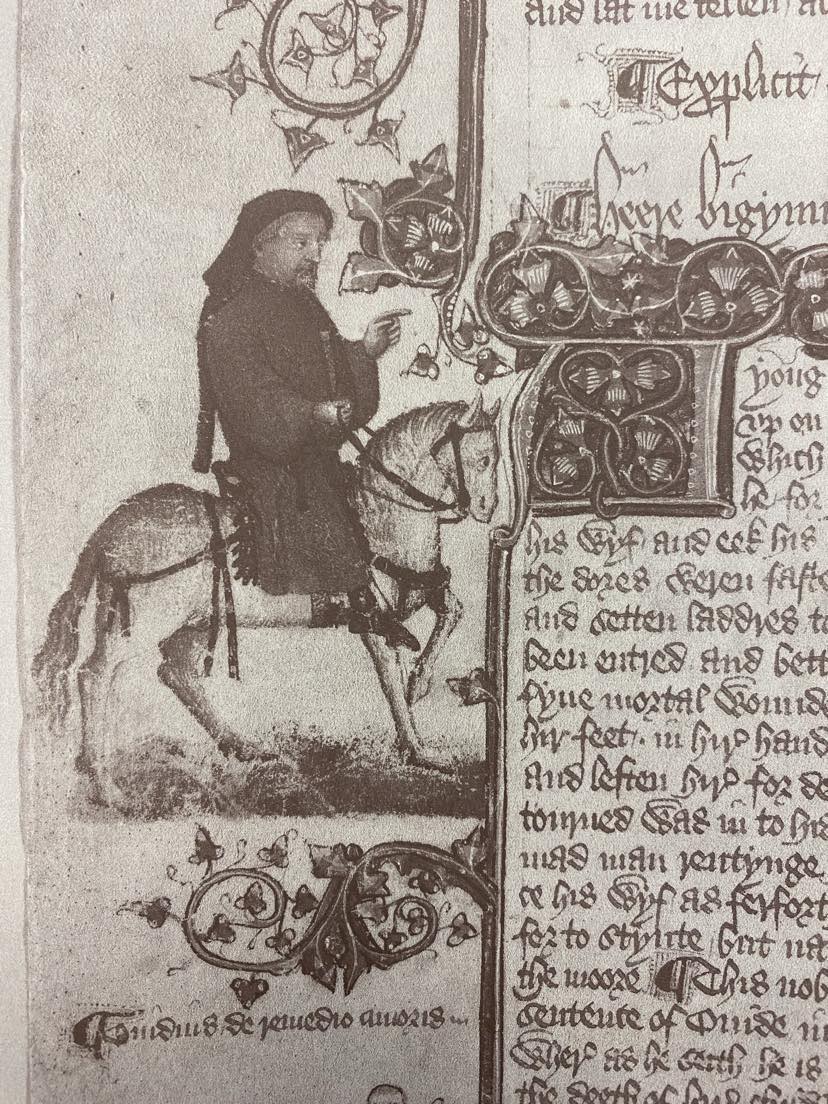

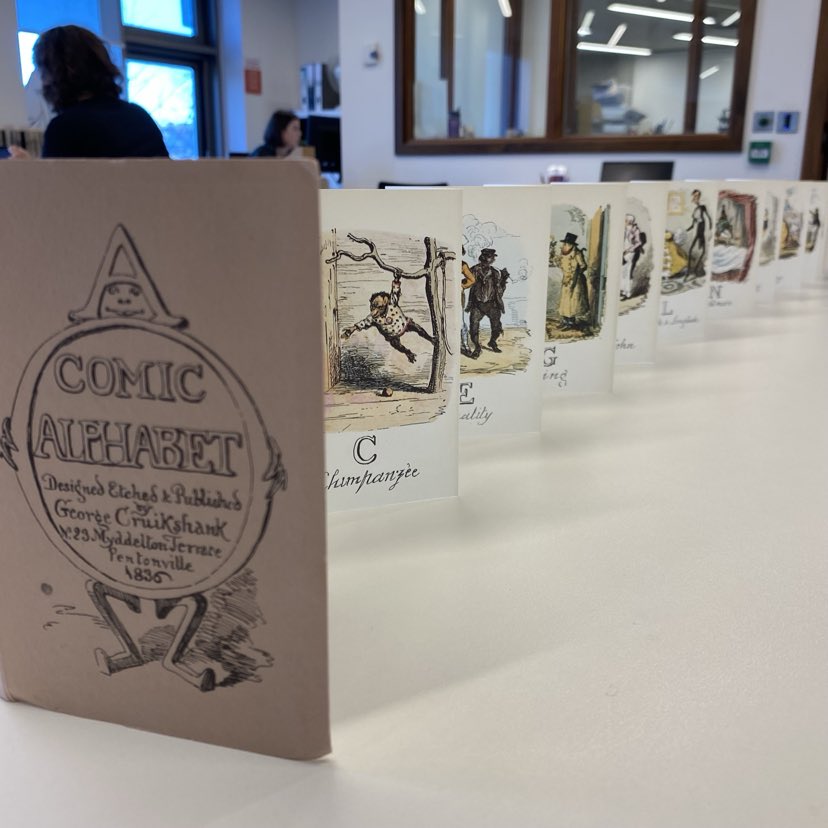

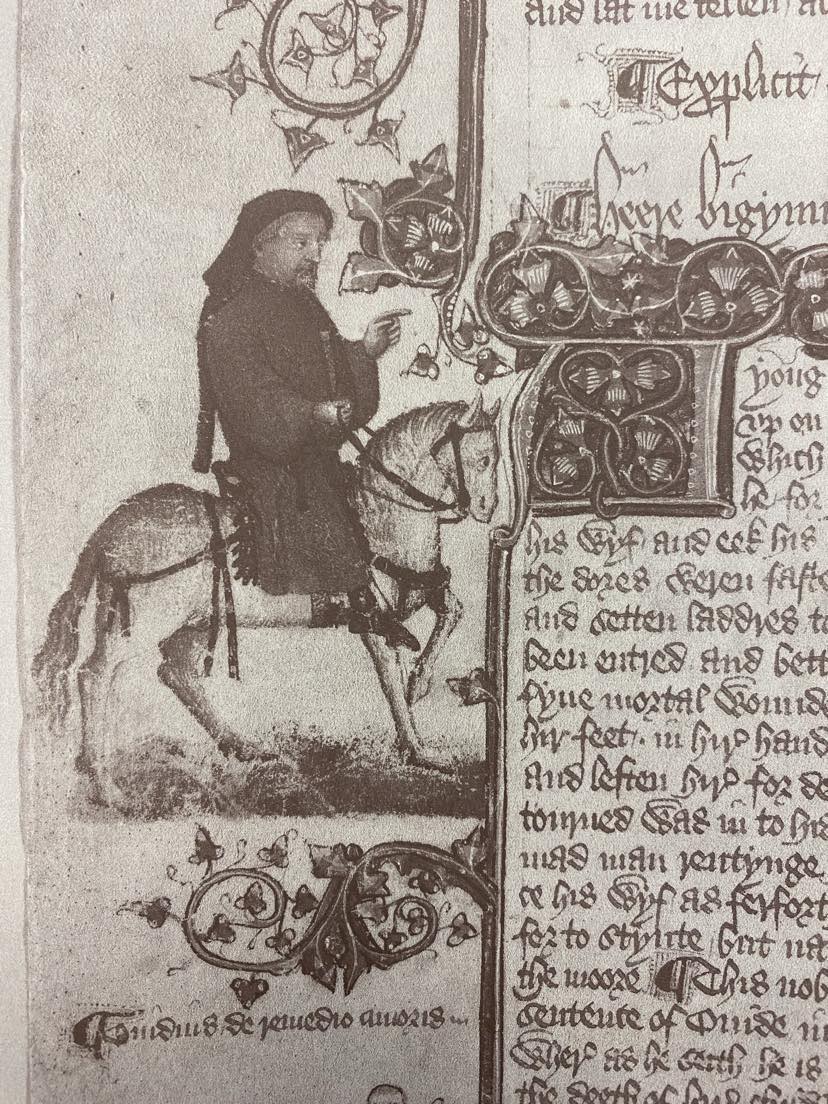

Earlier this year I did a #FacsimileFridays series on Instagram to shine a spotlight on what is often underprized and overlooked – for facsimiles are copies, not originals. However, they increase the circulation potential of unique items and thereby fulfil an important place in telling the history of the book. The knowledge I gleaned from many of these items also became pertinent to my teaching of a seminar on Chaucer this December for third year School of English students, in which we were considering very early manuscripts and print technology.

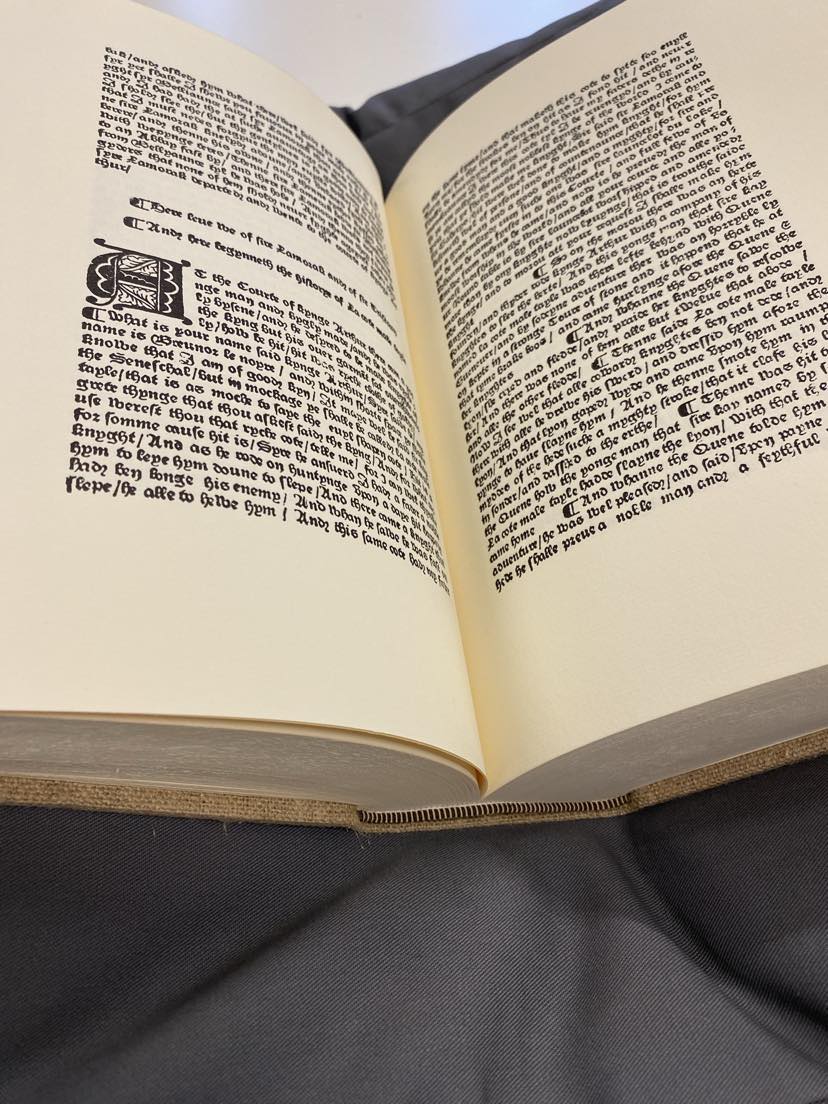

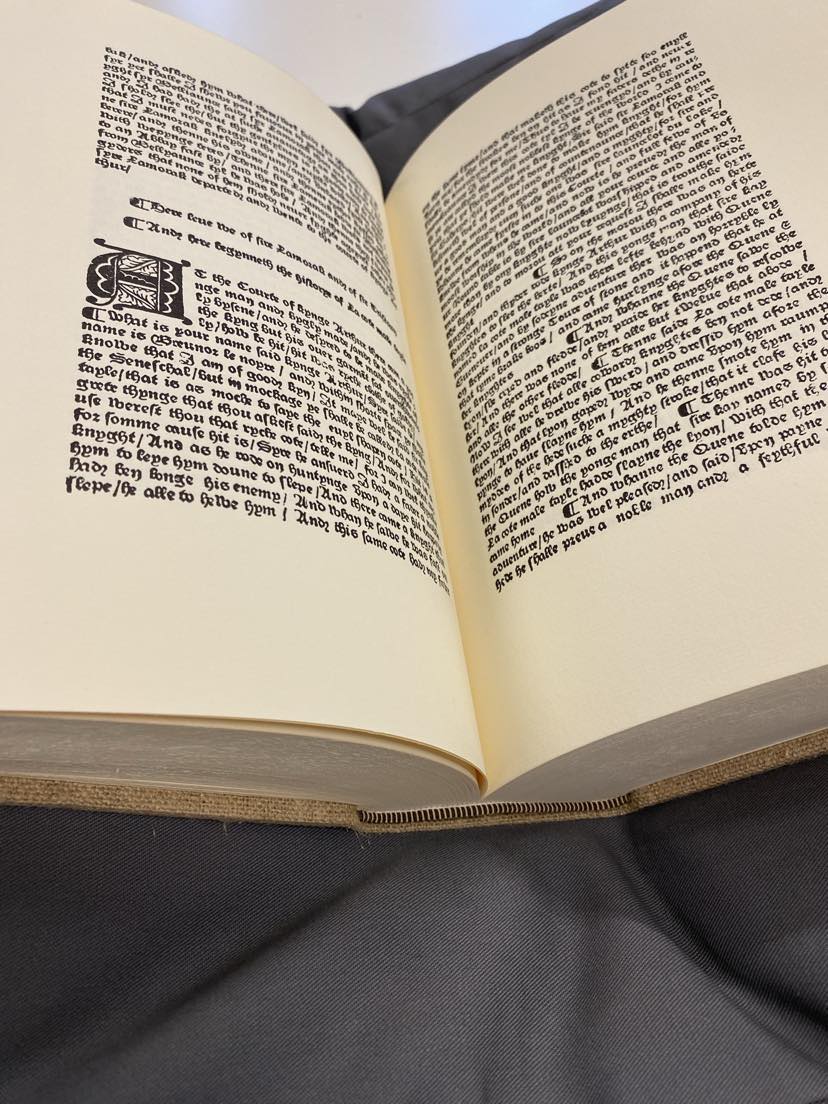

Produced between 1330-40, the Auchinleck manuscript gives an idea of reading practices pre-Chaucer: it consists principally of romances (think Arthuriana) along with other secular tales and religious pieces. Chaucer died in 1400, just before the advent of the printing press, and no copies of his works survive from his lifetime. The most famous of 15th-century manuscript versions of his work is undoubtedly the Ellesmere Chaucer, which became the authoritative example for organizing the Canterbury Tales. It’s written in the hand of a single scribe, and is incredibly grand both in its use of blank space and famous miniature illustrations of the Canterbury pilgrims. You may even be familiar with one of these, for its portrait of Chaucer is blown up on the side of the former Nasons building in the Canterbury high street! Now in the Huntington Library, our monochromatic facsimile still gives us access to the scale and content of the original. The first printing of the Canterbury Tales was William Caxton’s 1476 version, and the earliest printed version of Chaucer that we hold dates to 1598. With ‘Dorothy Smallwood’ inscribed on the title page, we know this copy once had female readership and it is also fascinating for its marginalia showing just how much its readers relied on a glossary to make sense of Chaucer’s language just 200 years after it was first circulated. William Caxton was also responsible for bringing Mallory’s Morte D’Arthur to an English audience, and we are really lucky to have a facsimile of this work because only one and a half of Caxton’s original version survive to date. Given the depth of the book, and the pressure reading puts on the spine, this is not surprising – original copies would literally have been read to pieces.

The Ellesmere Chaucer (F PD 1865 Classified sequence).

Le morte d’Arthur (Q PD 2040 Classified sequence).

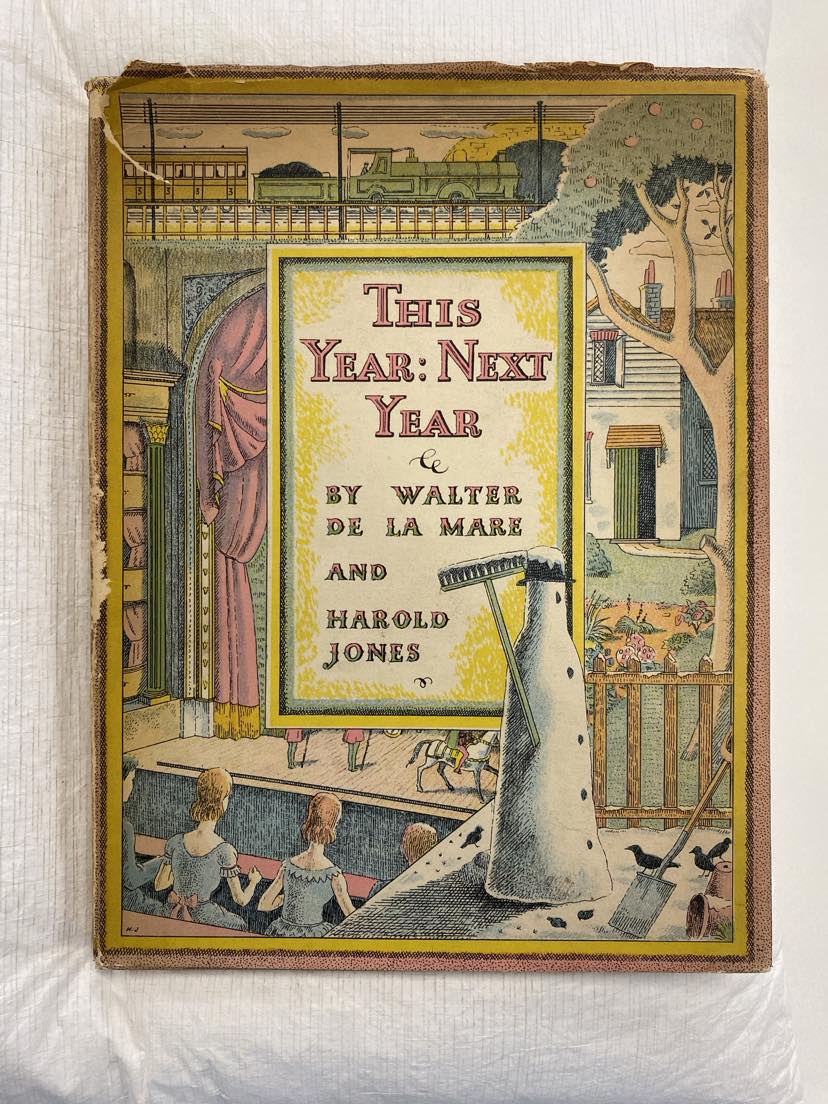

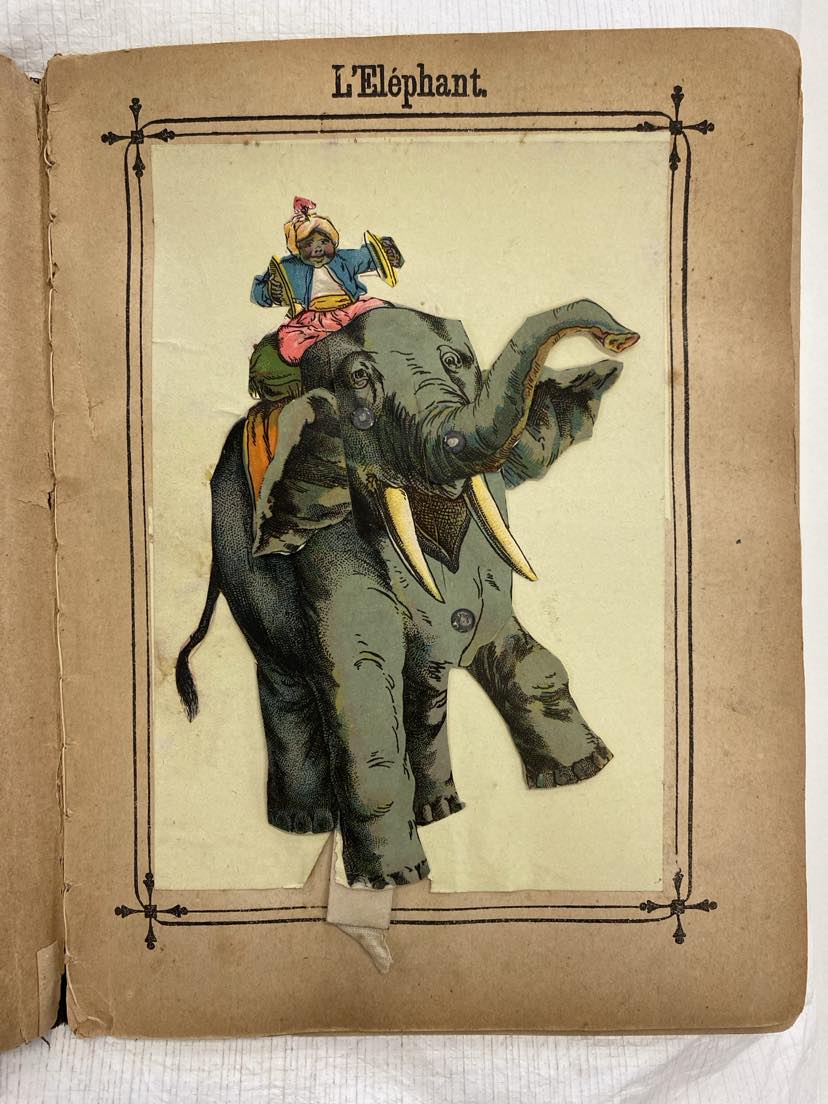

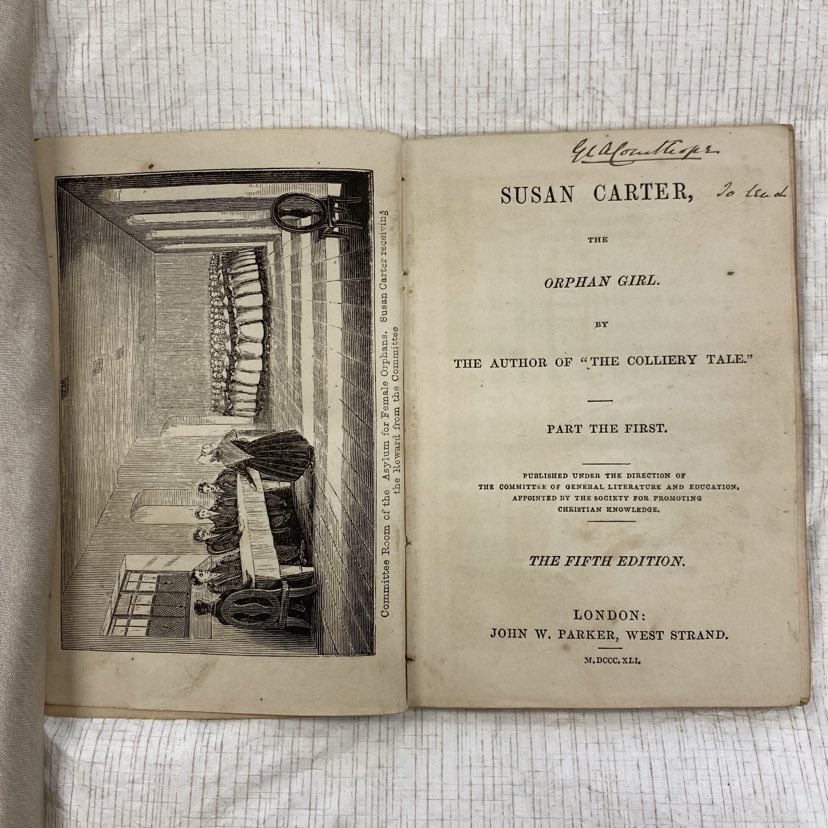

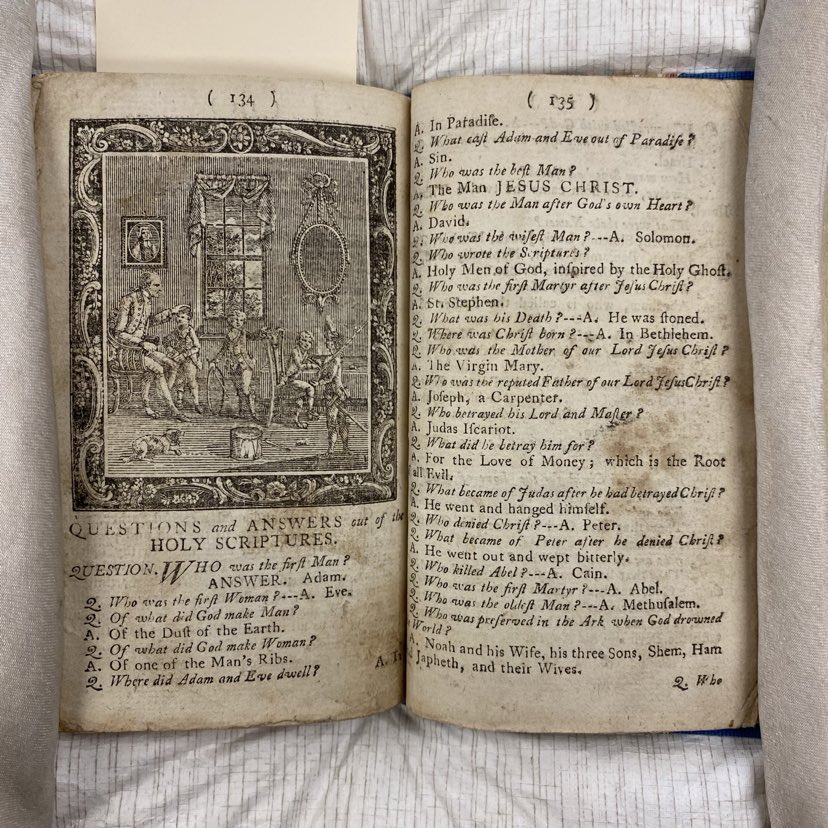

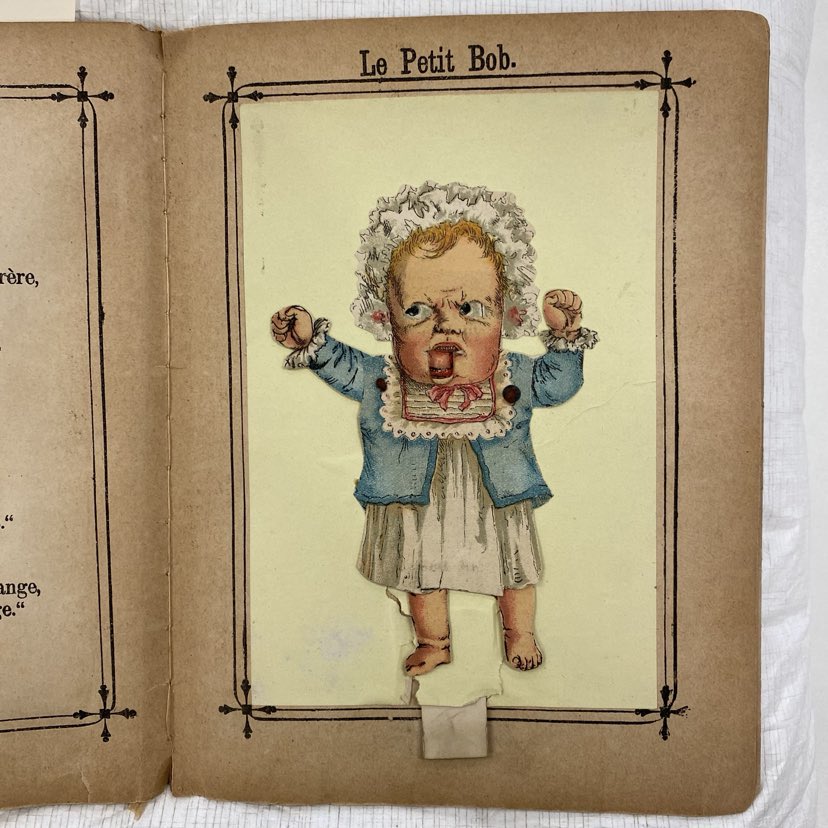

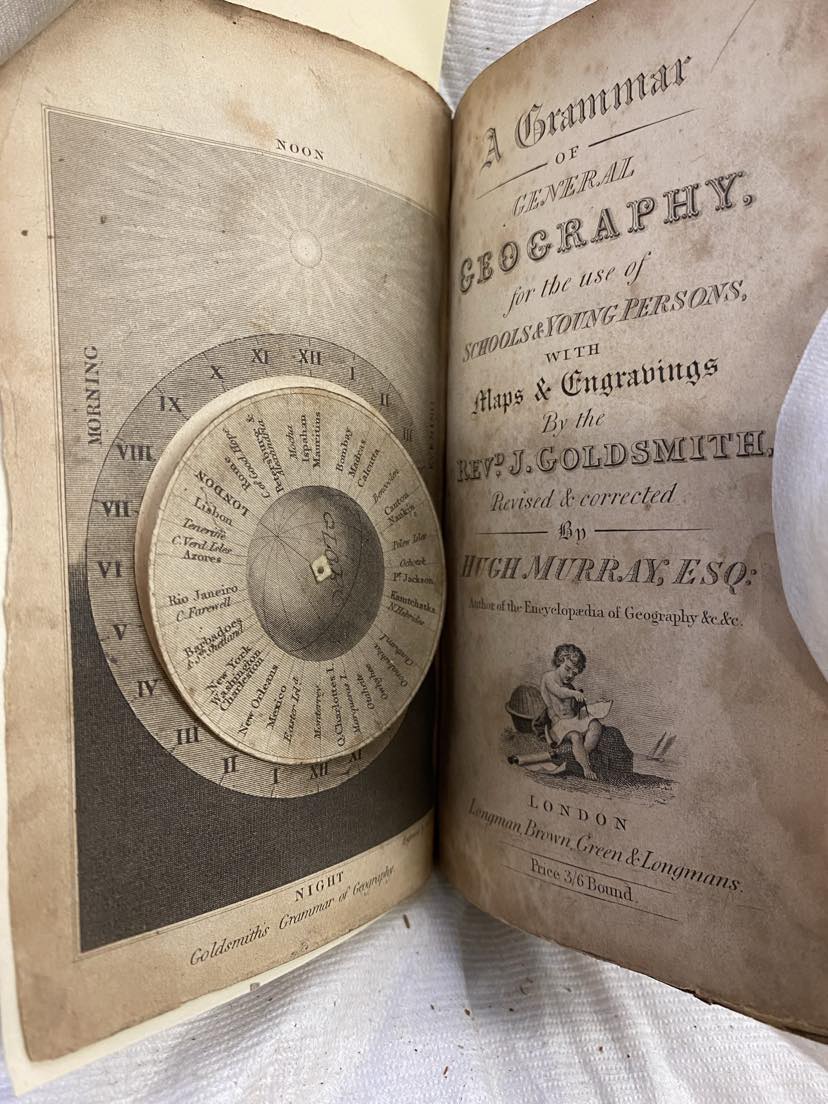

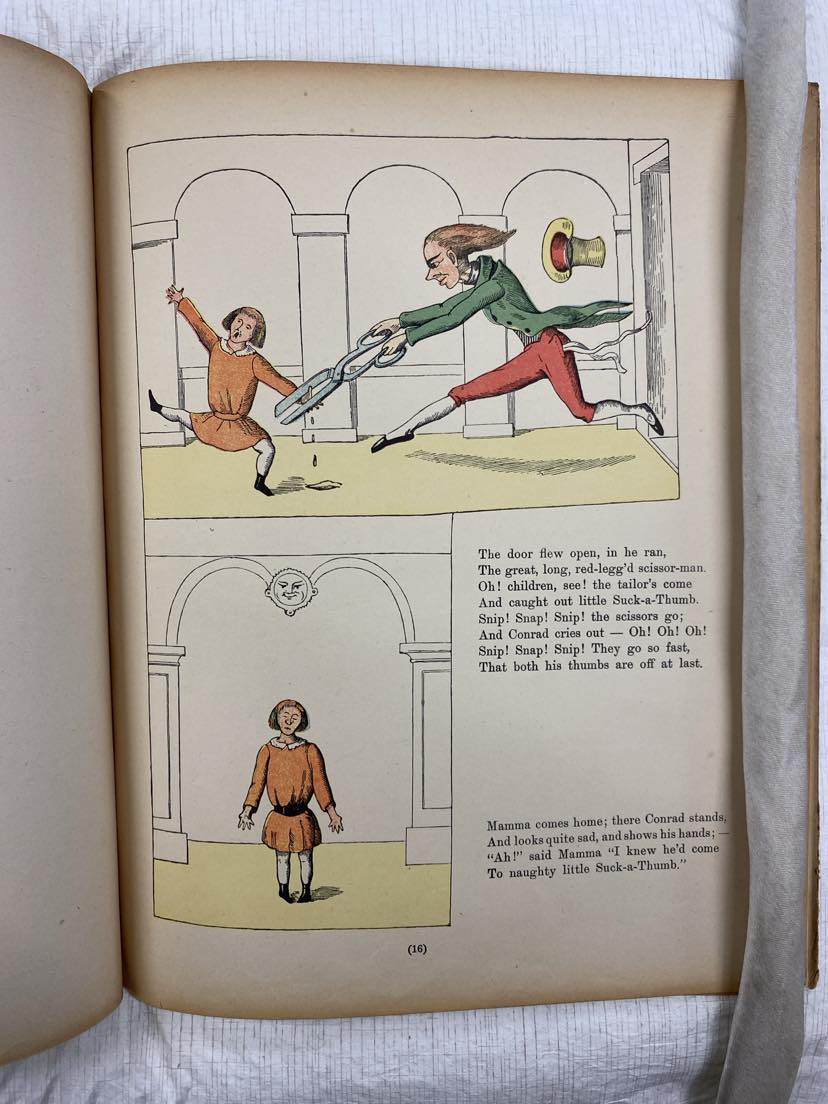

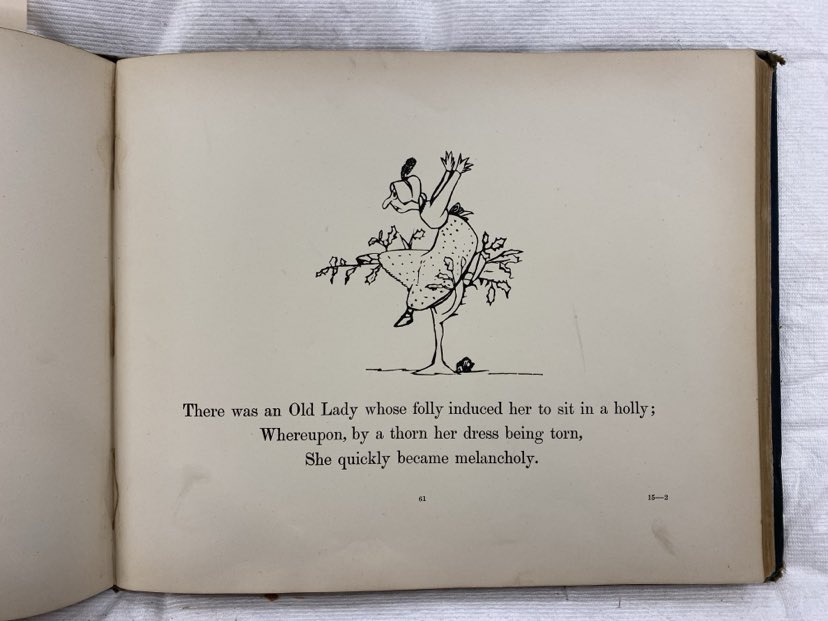

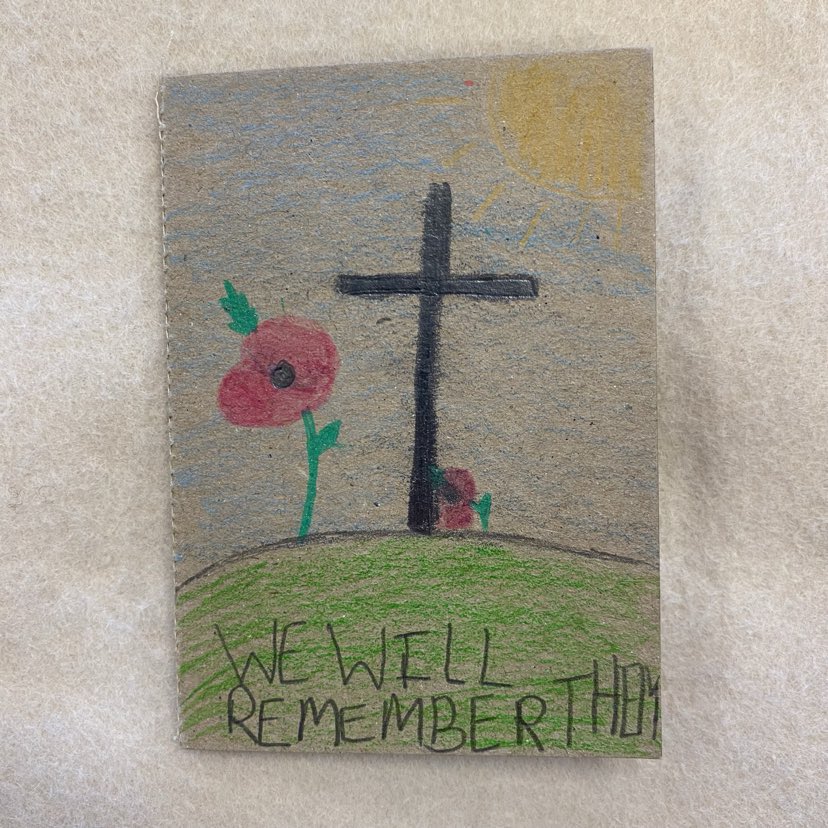

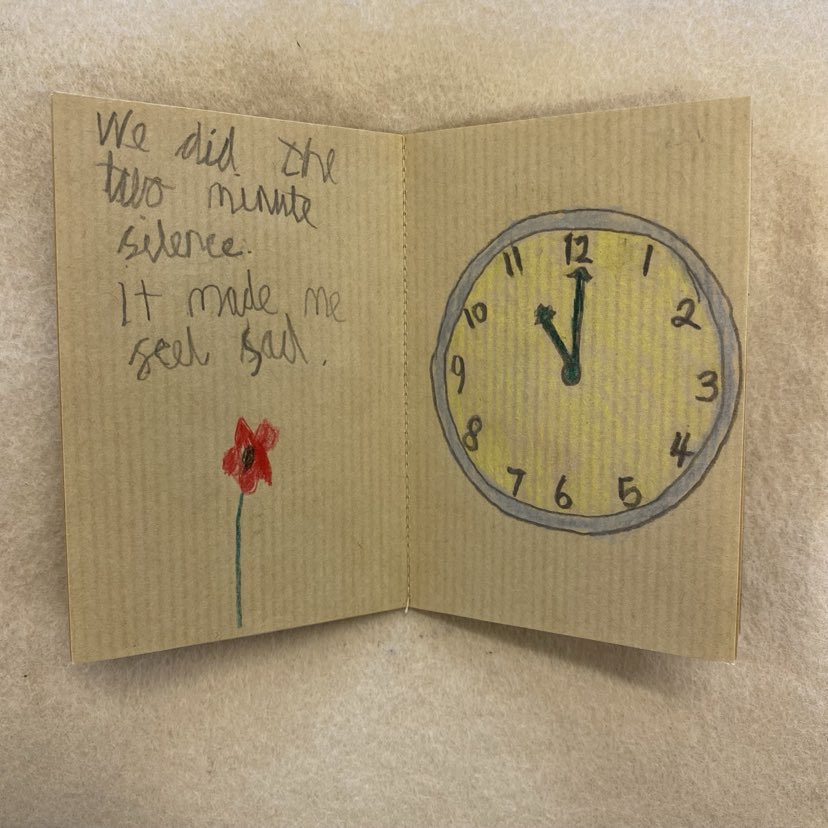

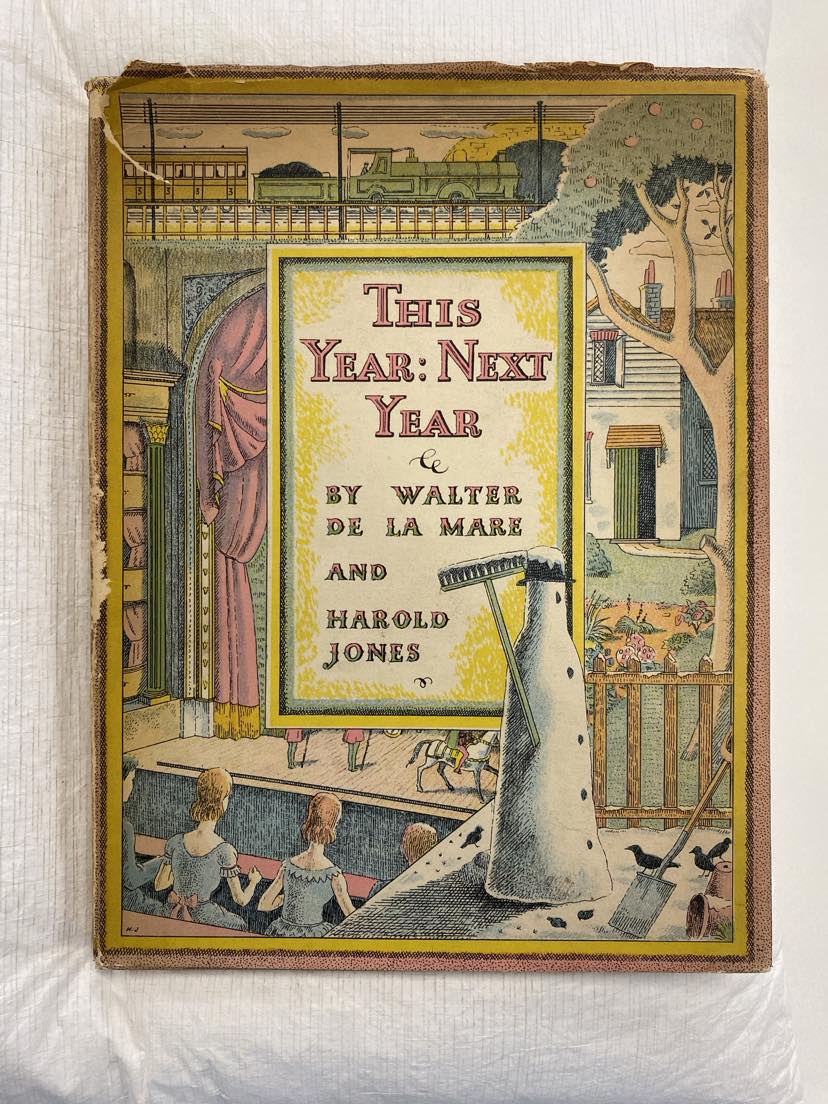

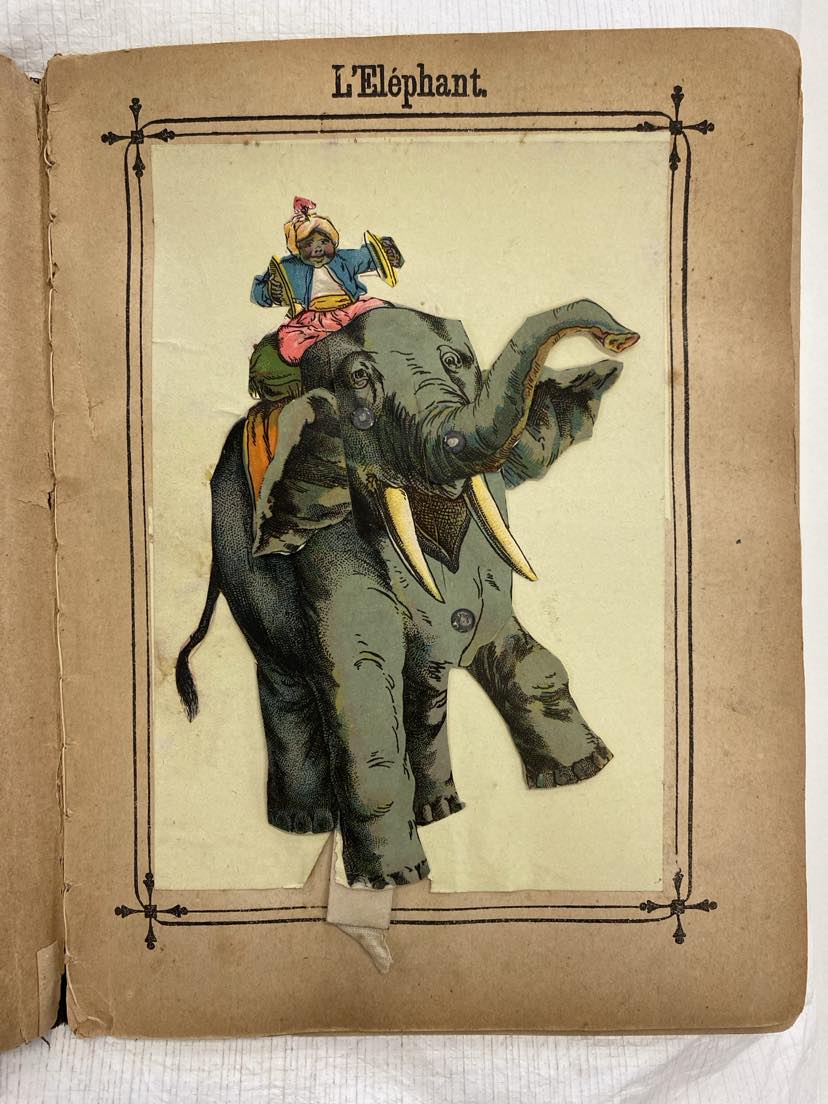

From the history of books to the art of books, I have had several opportunities this year to appreciate the variety of forms books can take and really get to grips with the non-textual components of books which is crucial to special collections cataloguing. In cataloguing our Children’s Literature Collection, I had to give condition and provenance notes as well as a physical description of each book, noting such varied features as illustrated fly-leaves, dust jackets, fold-out maps, pages of publisher’s advertisements, volvelle frontispieces and pop-up engineering. Children’s books are a joy to handle because they are so self-conscious of being tactile interactive objects, and they have proved inspirational – alongside our artist books – when displayed at book-making workshops led by Dr Stella Bolaki at Discovery Planet, Ramsgate. It has been a particular privilege for me to accompany our collections to a different venue off campus and engage different audiences, notably children, and witness them transpose their awe for special collections into creative responses.

This year : next year (PZ 8.3 DEL Children’s Literature Collection).

Les grotesques : en quatre tableaux (PZ 8 Children’s Literature Collection).

Mandy (Special Collections and Archives Assistant)

Over this past year I have been digitalizing our Hector Breeze collection, they are very interesting to scan and the way that they have been drawn.

HB0005, Hector Breeze Collection.

HB0011, Hector Breeze Collection.

I have also been scanning our cartoons collection, to see how they have changed over the last few years is so interesting, changes in the government also.

Sam (Project Digitisation Administrator)

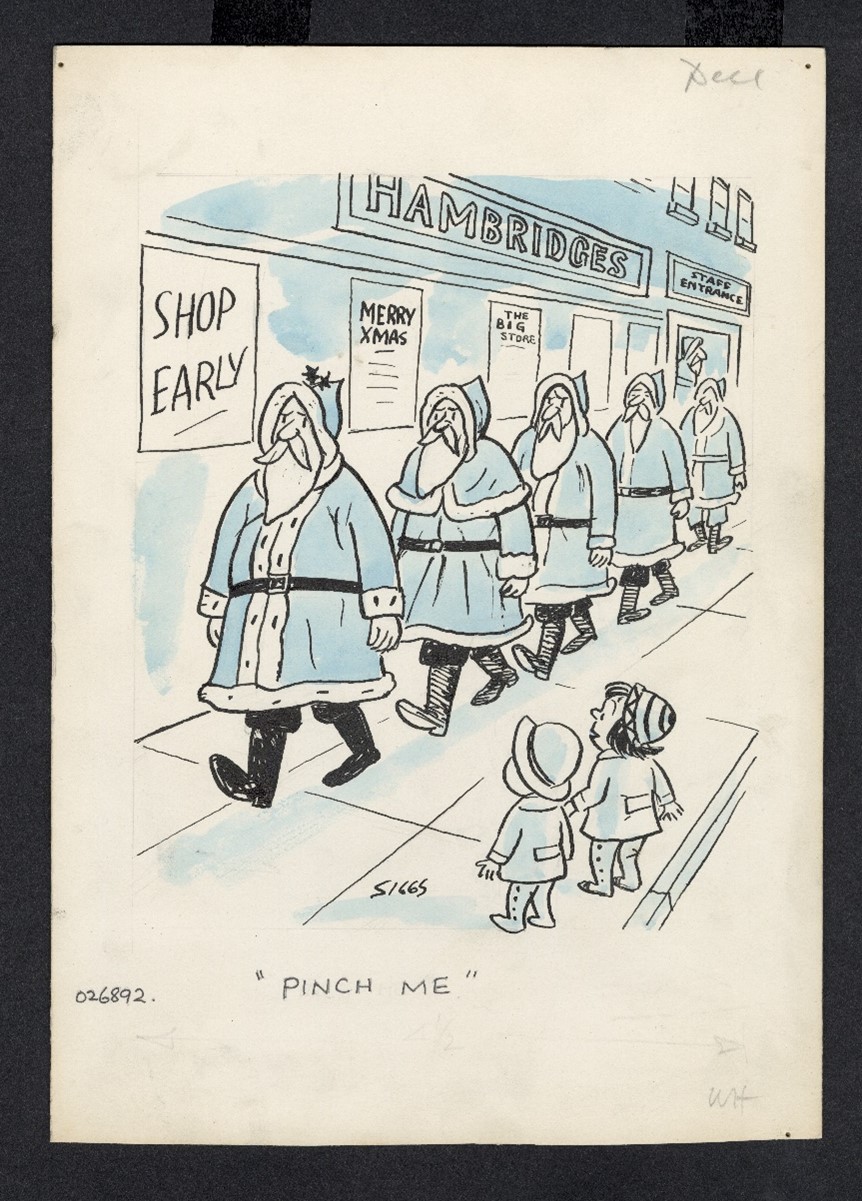

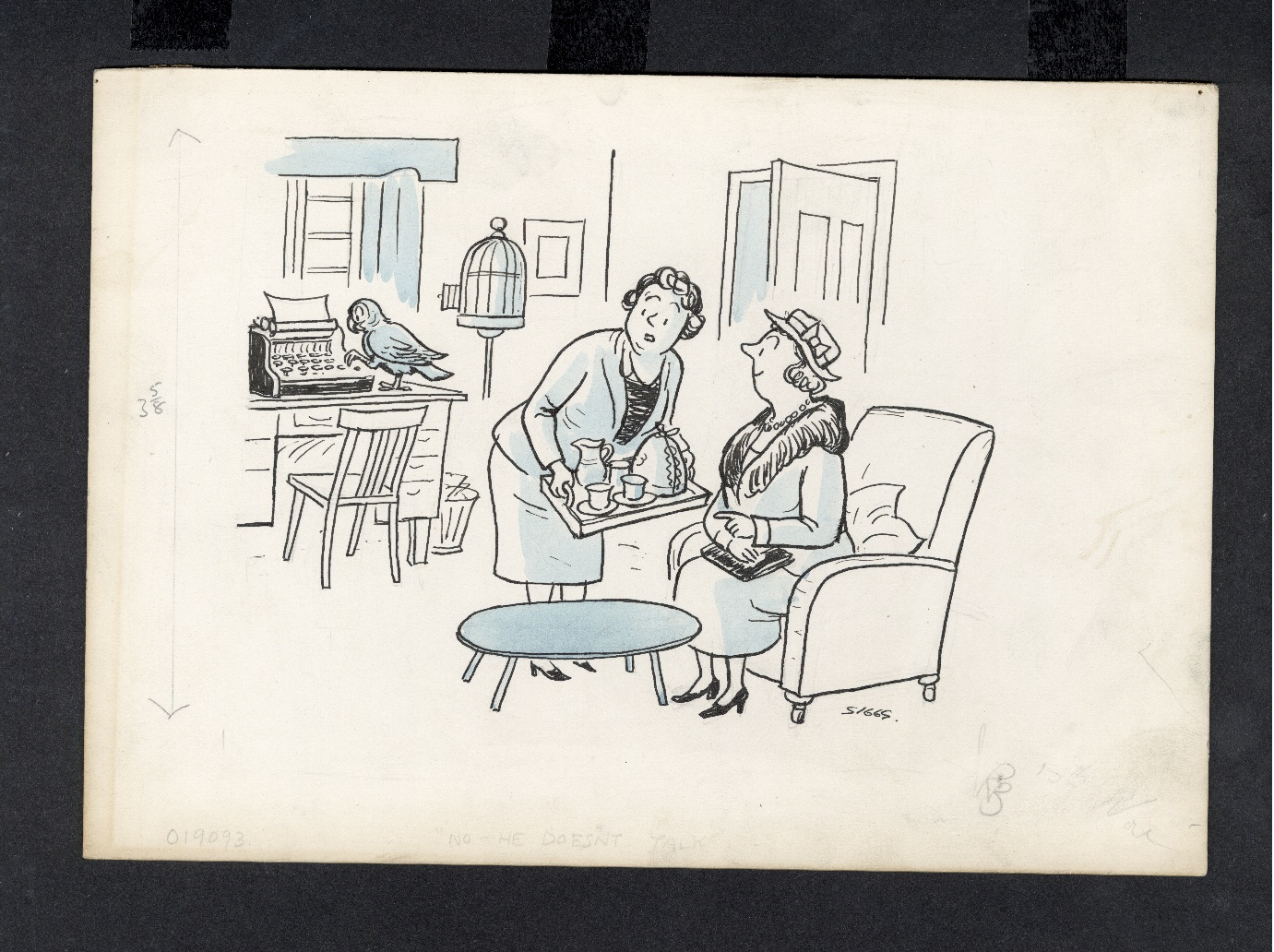

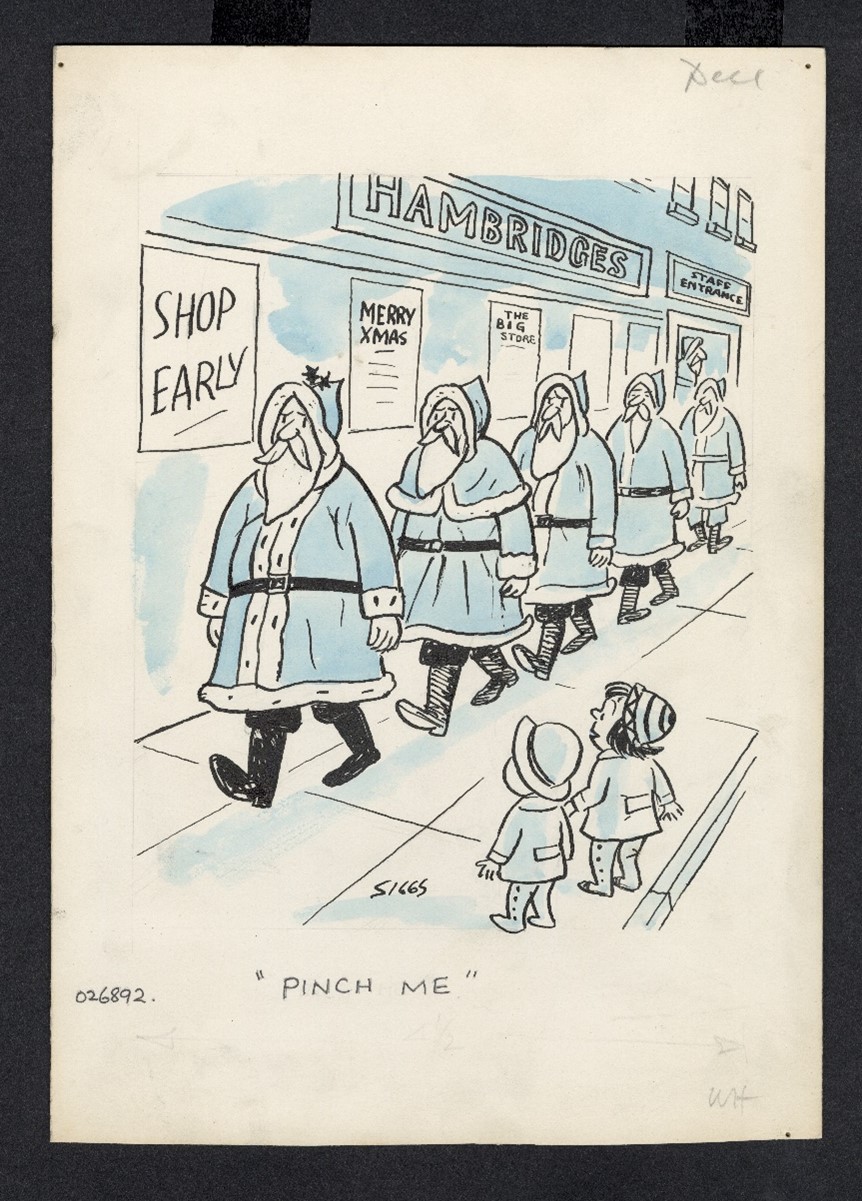

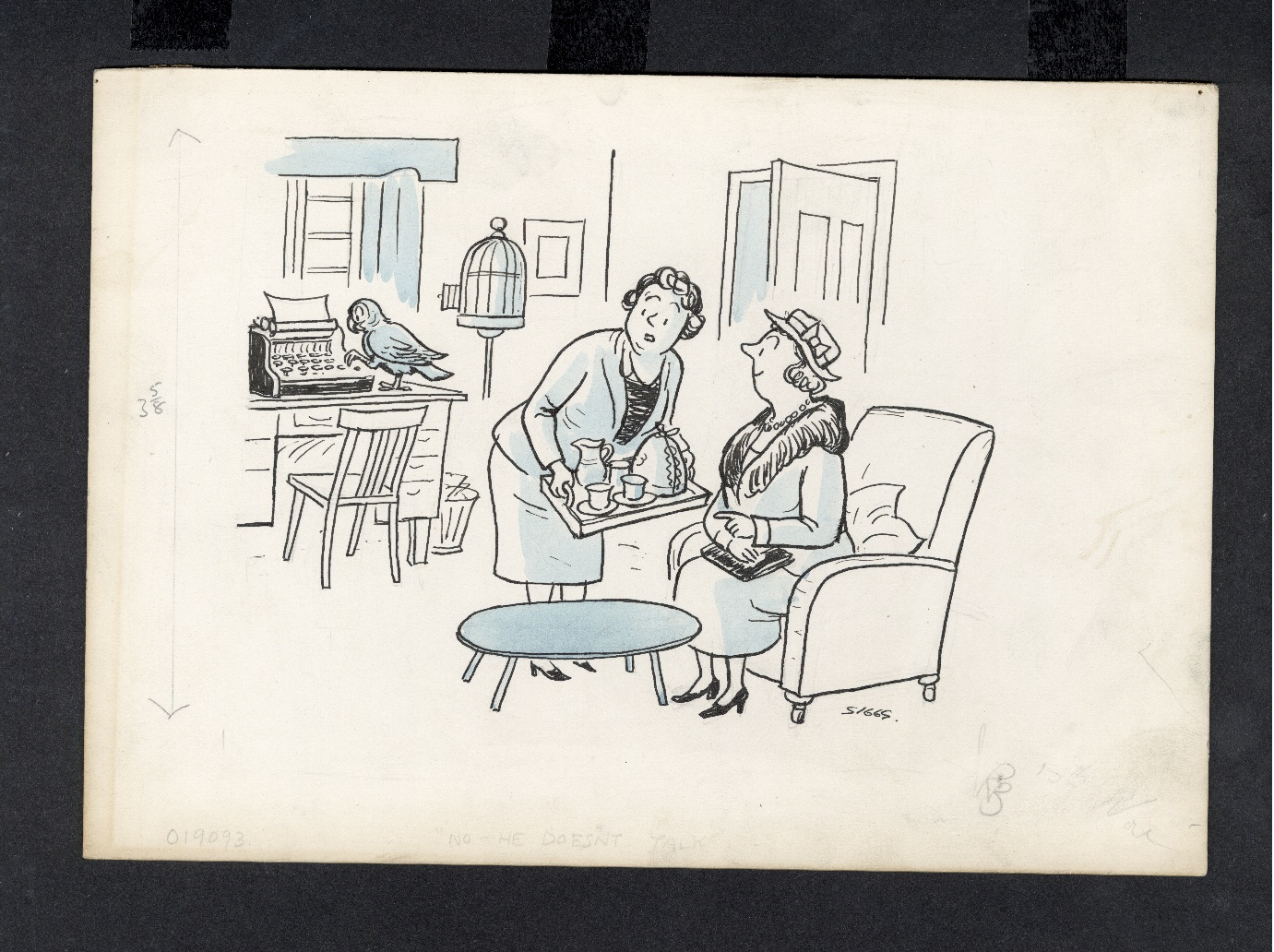

In my first year as an official member of the Special Collections team, I have been cataloguing and digitising the charmingly offbeat world of Lawrie Siggs (1900-1972), a cartoonist who worked for various publications (including Punch, John Bull and Lilliput) for 35 years.

Here are a few examples to set the tone.

Pinch Me, SIG0307.

No He Doesn’t Talk, SIG0319.

Jacqueline (Curation and Discovery Administrator)

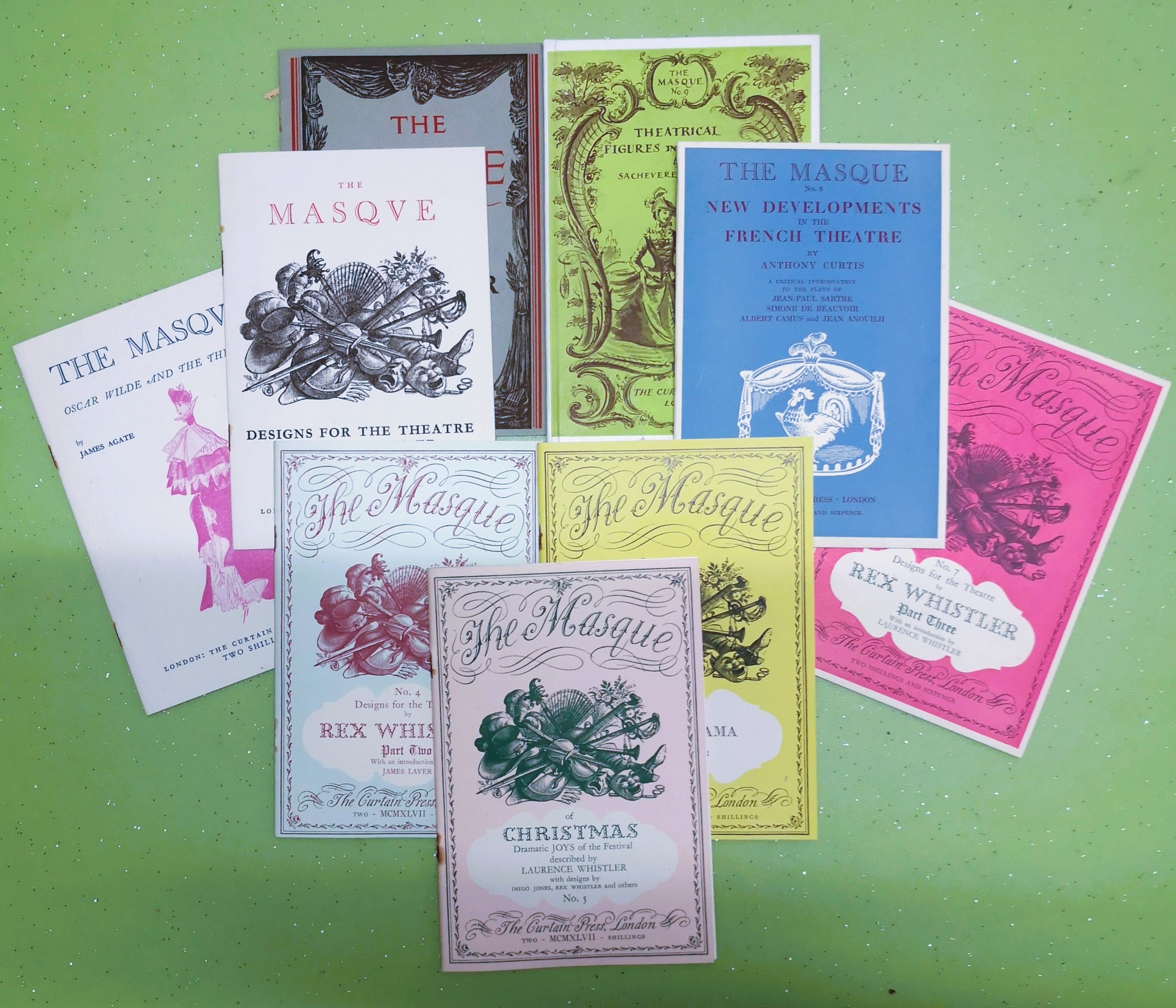

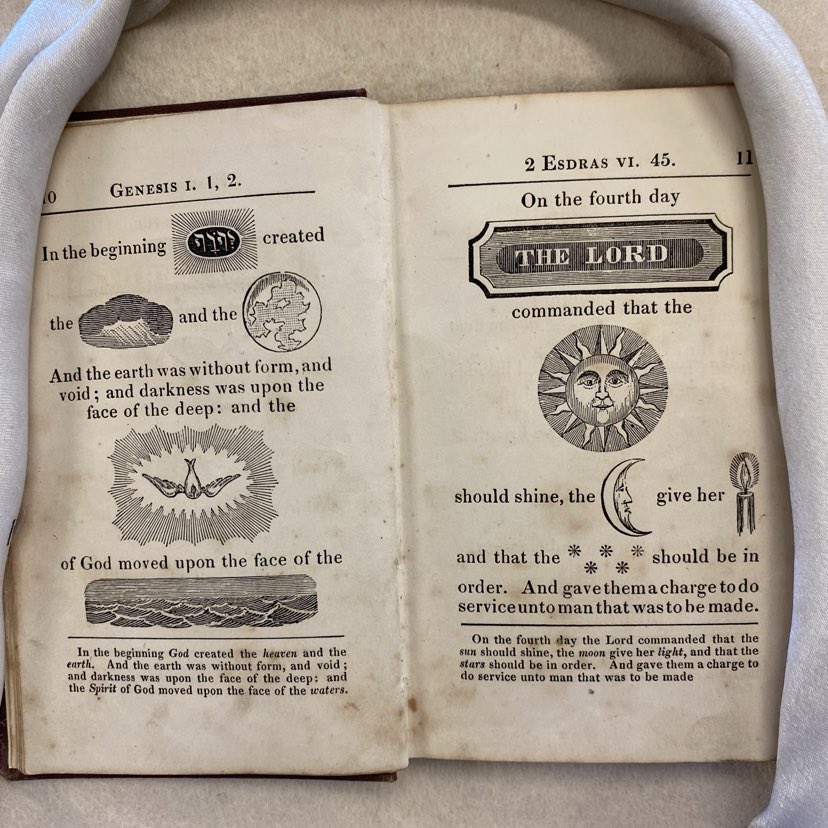

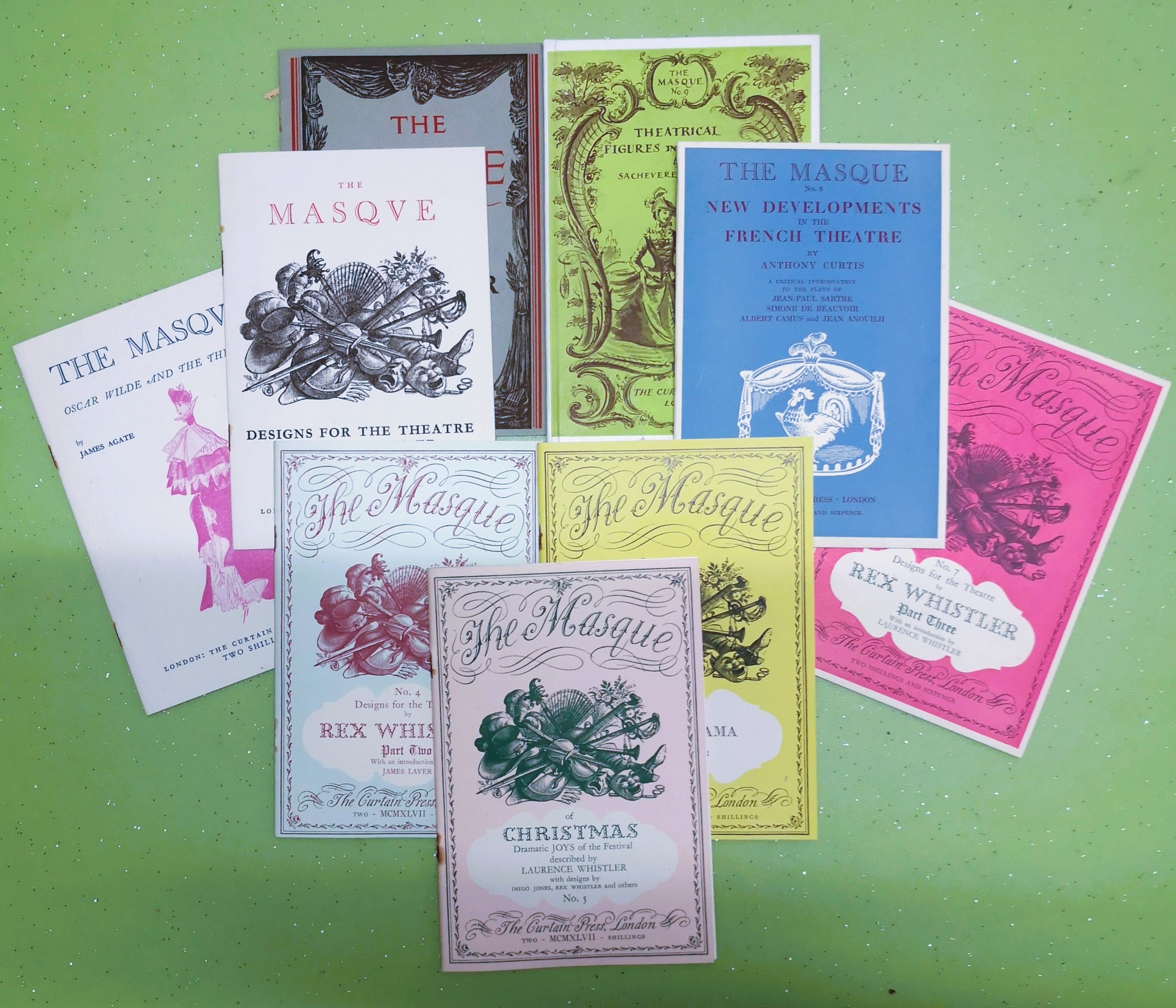

The theatre designer Edward Gordon Craig described himself as “fond of print.” His designs for theatre stage sets and scenery surpassed possibility in his time and he turned to typography and woodcuts. I have spent this year with the collections of three men who can all be described as fond of print. Arnold Rood’s collection is centred around Gordon Craig and his circle. It includes Craig’s woodcuts in print. I began the year at the end of Carl Giles’ collection (the cartoonist Giles) where I found a set of Puffin Picture Books from the 1940s-50s, their design and illustrations redolent of a return to delight in books after austerity. After Rood, I’ve been cataloguing the periodicals in Jack Reading and Colin Rayner’s collection; they were thorough collectors who focussed on theatre and literature. Last week amongst odd issues I came across a complete set of The Masque, a small and pretty journal of 9 issues each one on a theme. Issue 5 is The Masque of Christmas, presenting dramatic JOYS of the season to you.

The Masque, Reading-Rayner Literature Collection.

Stu (Curation and Discovery Administrator)

Over 90 titles added to British Cartoon Archive Library this year. Most memorable was probably the stunning cold war era illustrations in, Drawing the curtain : the Cold War in cartoons / Althaus, Frank.

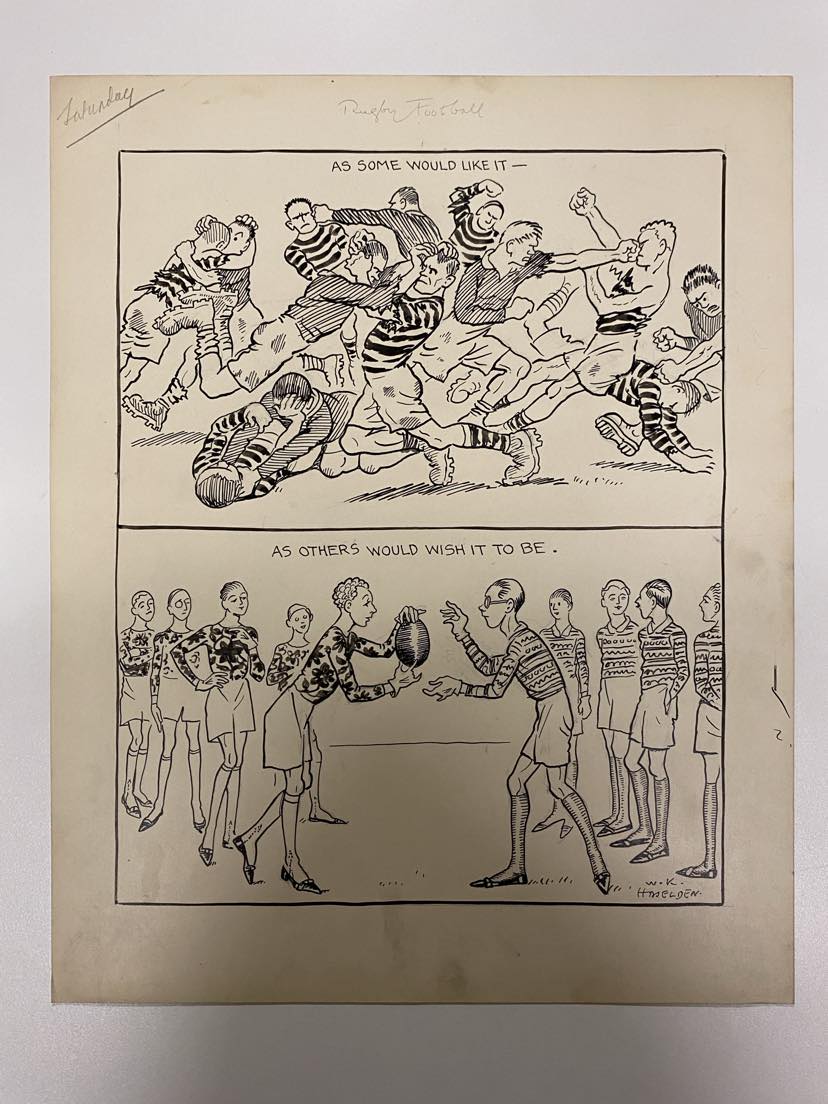

Also Daily Mirror reflections : being 100 cartoons (and a few more) culled from the pages of the Daily Mirror. [Vol. I] / Haselden, W. K. (William Kerridge), 1872-1953, formerly owned by prime minister Stanley Baldwin.

Quite moving and of current topical interest, A child in Palestine : the cartoons of Naji al-Ali / ʻAlī, Nājī.- This collection of drawings chronicles the Israeli occupation, the corruption of the regimes in the region, and the plight of the Palestinian people. The images have bold symbolism and starkness to them.

The bottle / Cruikshank, George, 1792-1878, – This is a really interesting little pamphlet promoting temperance through a cautionary tale of the downfall of a family brought about by the evils of drink. No publication date but probably late 19th century.

Matthias (Curation and Discovery Administrator)

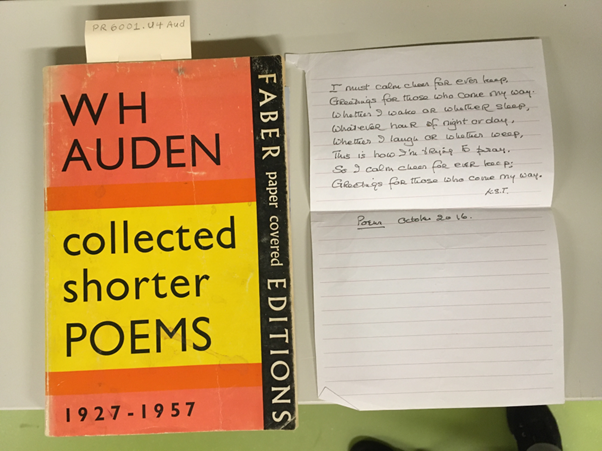

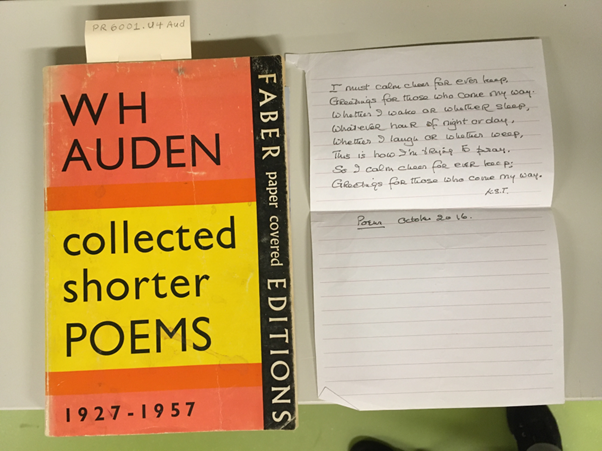

I have been working on the Shirley Toulson Collection this year, a collection of over 400 poetry books from the estate of the late author and poet Shirley Toulson. Handling a writer’s private library felt very special and personal. The books, many of them rare editions by small presses, often had personal notes and handwritten dedications by the authors. Often I found postcards or letters inserted between the pages. My personal highlight was a handwritten, seemingly unpublished poem by Shirley Toulson I found inside a W.H. Auden poetry volume.

Collected shorter poems 1927-1957, PR 6001.U4 AUD Shirley Toulson Poetry Collection.

Our reading room will be closed from 16th December 2023 and will reopen 16th January 2024 – we hope you all have a very happy and peaceful break.