In keeping with our Theatrical Thursdays theme on principal players, this post is dedicated to three eighteenth-century celebrities: Mary Robinson (1757-1800), Dorothea Jordan (1761-1816), and Sarah Siddons (1755-1831). All three make an appearance in our 1798 volume of The Lady’s Magazine which I’ve previously written about here as well as other theatrical works and women’s periodicals held in Special Collections and Archives. Women’s periodicals of this time are particularly fascinating for how they contributed to, and participated in, a growing consumer and celebrity culture. They were as much interested in what women did as what they wore – and we’re going to follow suit and explore both too.

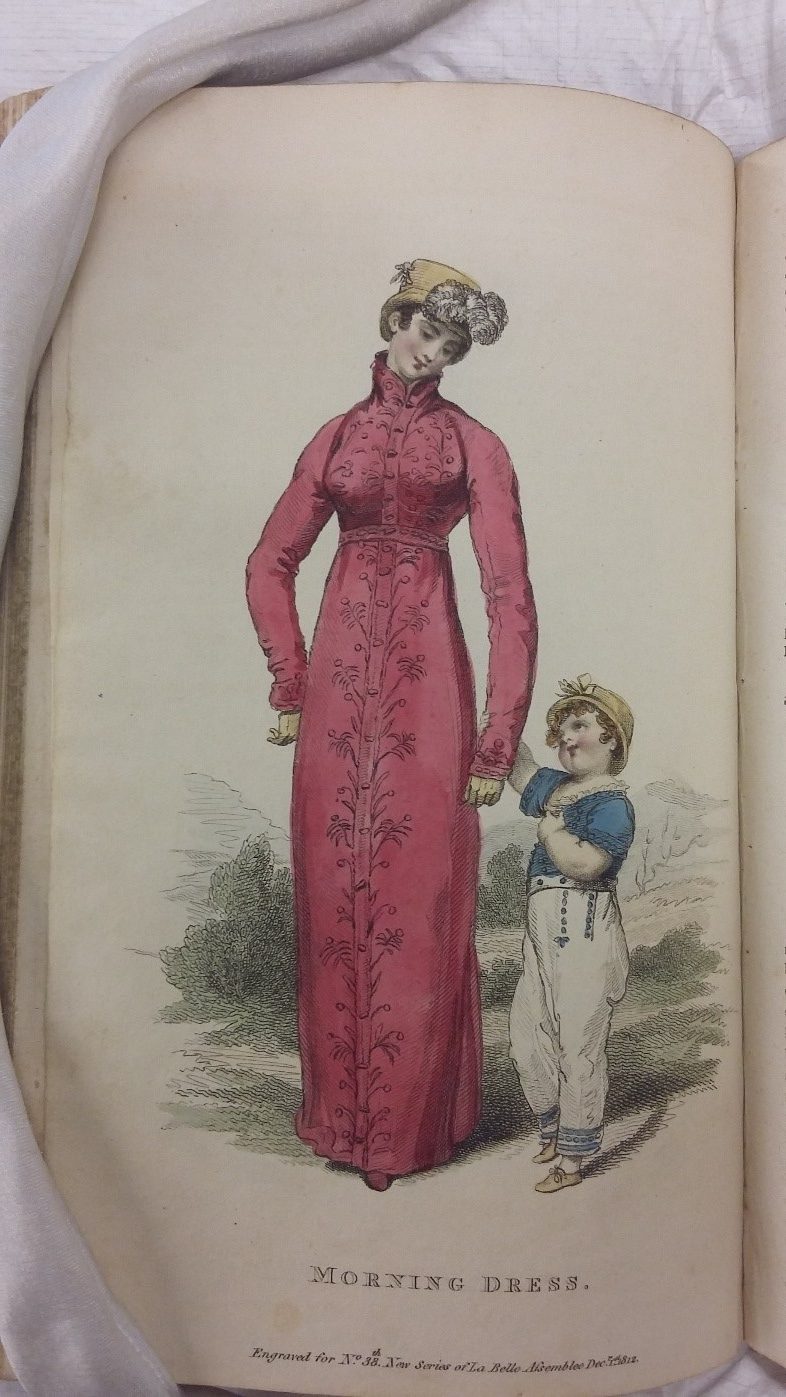

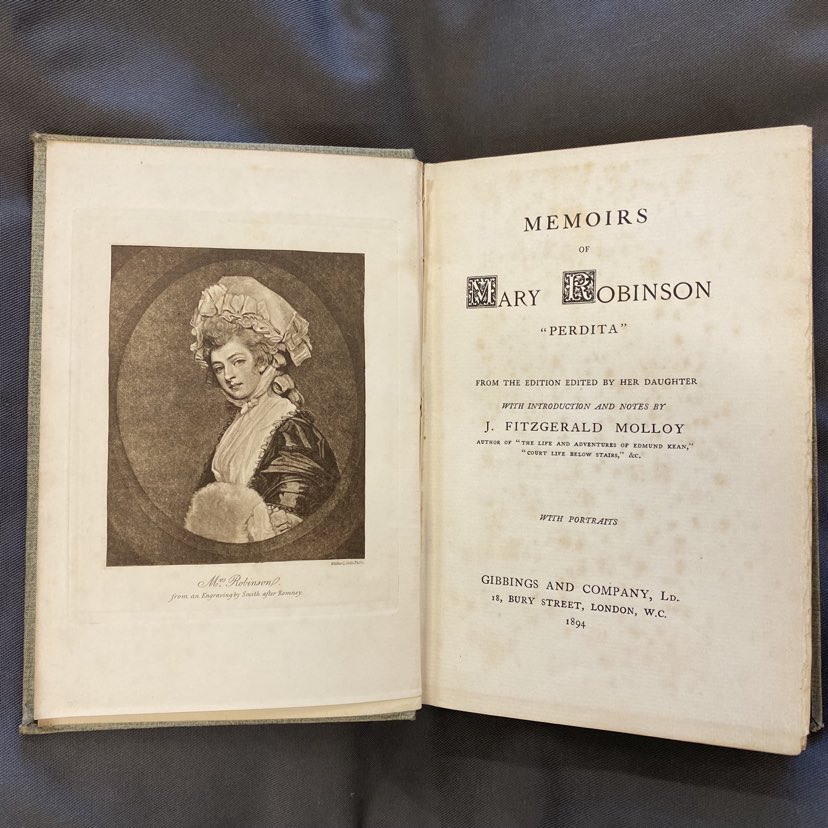

By the time our copy of The Lady’s Magazine was published in 1798, Mary Robinson was destitute – financially and physically – having suffered a mysterious injury during a carriage ride that left her crippled. In her early twenties, she was an eighteenth-century Icarus, shooting to public attention as the Drury-Lane actress that captured the young Prince of Wales (later George IV), becoming his acknowledged mistress and taking her Shakespearean role of Perdita off-stage and off-script. She became a target for all sorts of media attention, from gossip columns to satirical prints. Also acknowledged, however, was her astonishing sense of style, which rivalled that of the Duchess of towering-plumes Devonshire – who was, incidentally, also her literary patron. Despite her tragically short life, her literary achievements number several novels, plays, poems and political tracts. In April 1798, The Lady’s Magazine printed ‘Farewell to Glenowen’ from the risqué novel Walsingham (1797), a story which charts the adventures of the cross-dressed heroine ‘Sir’ Sidney Aubrey. This deceit of dress was a popular plot device in the eighteenth century; irl, it was reserved principally for the stage, though aspersions were cast that Robinson assumed breeches during her dalliance with the Prince. She penned her own version of events in her Memoirs (1801), and Special Collections and Archives holds a late nineteenth-century copy filled with delicious details of her dresses, and illustrated with black and white plates (copies of portraits made during her lifetime). Fig. 1 gives a glimpse of early 1780s fashion, and Robinson is deliberately cultivating a domesticated look here with her pigeon-breasted fichu and mob-cap.

Fig. 1 Mary Robinson, Memoirs of Mary Robinson, “Perdita” (1894) – Reading-Rayner Theatre Collection (SPEC COLL SCRP 6.33)

Whilst Robinson is represented in The Lady’s Magazine principally as a poet, Dora Jordan and Sarah Siddons ranked amongst the most famous actresses of their day, and were respectively famed as the muses (aka queens) of Comedy and Tragedy. These lofty titles reflect the neo-classical flavour that came to characterise Regency culture, from the ionic columns in architecture to the elongated silhouettes of high-waisted muslins. Thalia (Comedy) and Melpomene (Tragedy) were, moreover, positioned above the proscenium arch and thus part of the iconography of Drury Lane Theatre where Jordan and Siddons were seen to perform. What is interesting, however, is how these actresses’ titles became cemented through the press, and through women’s magazines in particular.

The Lady’s Magazine reported eagerly on London’s theatre scene throughout its run, giving regular accounts of new plays and comments on performers. The February issue for 1798 mentions Jordan in relation to Thomas Holcroft’s Knave or not, newly penned and produced at Drury Lane on 25th January that year. Unlike Mary Robinson, Dora Jordan survived the scandal of becoming a royal mistress – rather than a fling, she and the Duke of Clarence (later William IV) had a proper relationship; he became her protector, and by 1798 they’d had four children and were enjoying domestic harmony together at Bushy House. This stability perhaps enabled Jordan to keep up her industrious stagecraft and professional identity, and she never needed to pen memoirs to resuscitate a fallen reputation (despite the castigation she endured from the satirical press). Jordan was especially renowned for her singing voice and shapely legs, the latter discerned through her portfolio of breeches and travesty roles: Rosalind, Viola, Fidelia, Sir Harry Wildair, etc. The report of her performance in The Lady’s Magazine is complimentary in general, and emphasises the ‘commensurate applause’ she received. Jordan portrayed the character Susan Monrose, described as ‘an awkward but honest and sincere country girl.’ This part is designed to contrast with the ‘chaste, elegant, and pathetic’ part of sentimental heroine – Aurelia Rowland – played by Marie Thérèse Du Camp (who would, incidentally, become Sarah Siddons’ sister-in-law on marrying her actor-brother Charles Kemble in 1806).

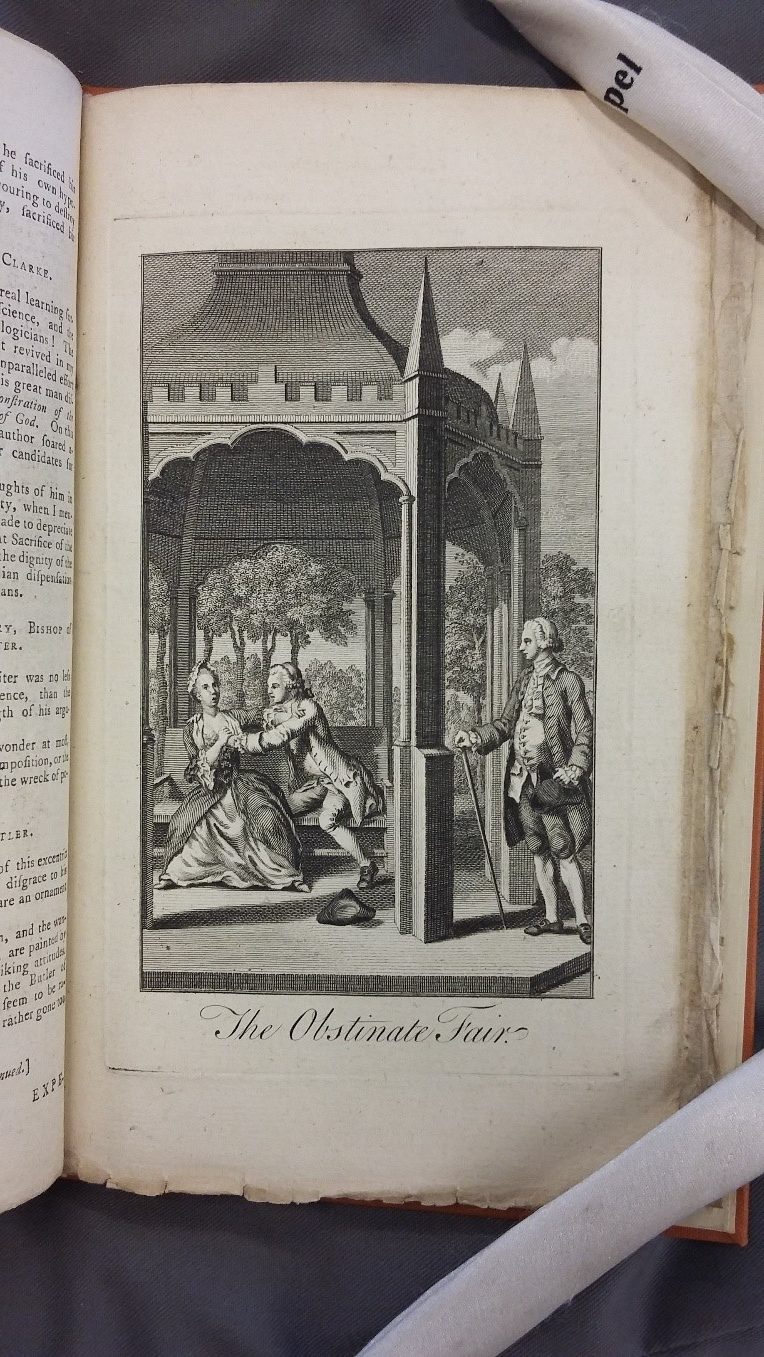

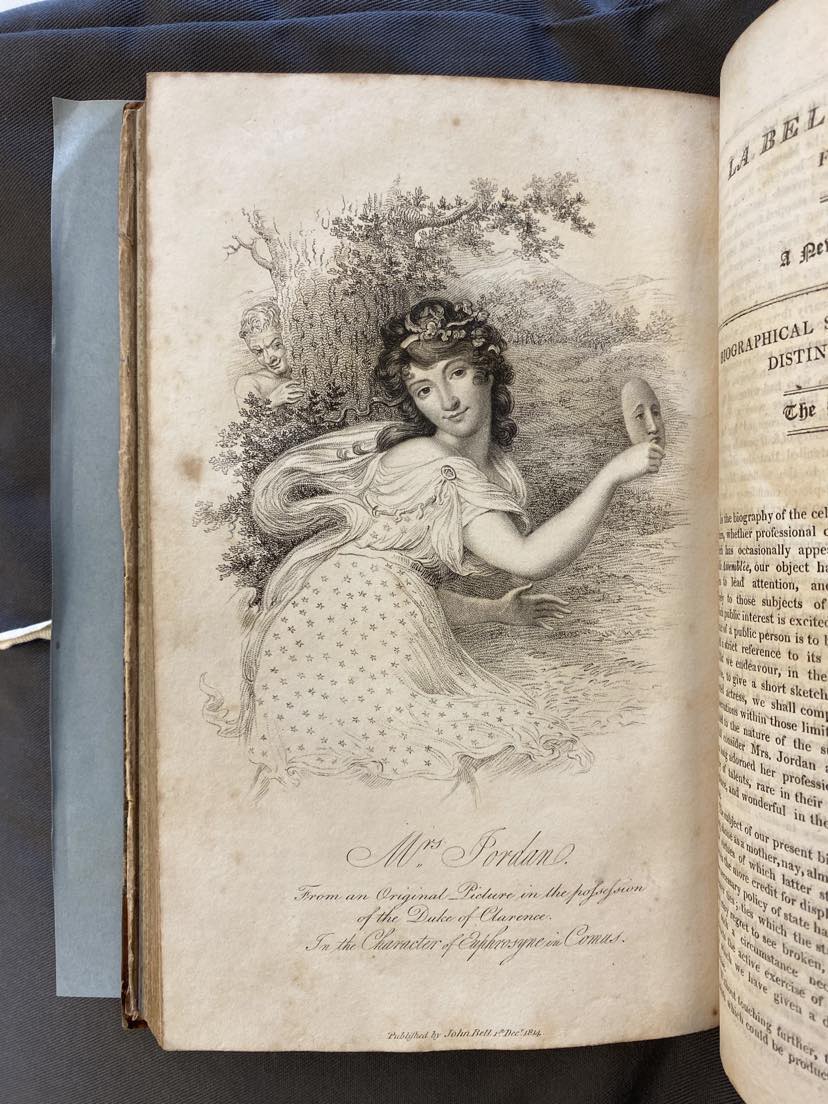

The ‘country girl’ was a stock character of eighteenth-century comedy; she had a licence to flirt but stayed safely on the side of virtue – she was, in short, an incarnation of the comic muse. In the context of The Lady’s Magazine, ‘country girl’ is used as a shorthand that truncates Jordan’s theatrical repertoire into a single denomination – it ensures that this becomes the primary part-type for which she is known. Jordan made her London debut in 1785 playing the part of Miss Peggy, the titular heroine of David Garrick’s The Country Girl (1766) – an adaptation of William Wycherley’s The Country Wife, to whom copies are sometimes falsely ascribed (as is the case of the copy in Special Collections, see Fig. 2).

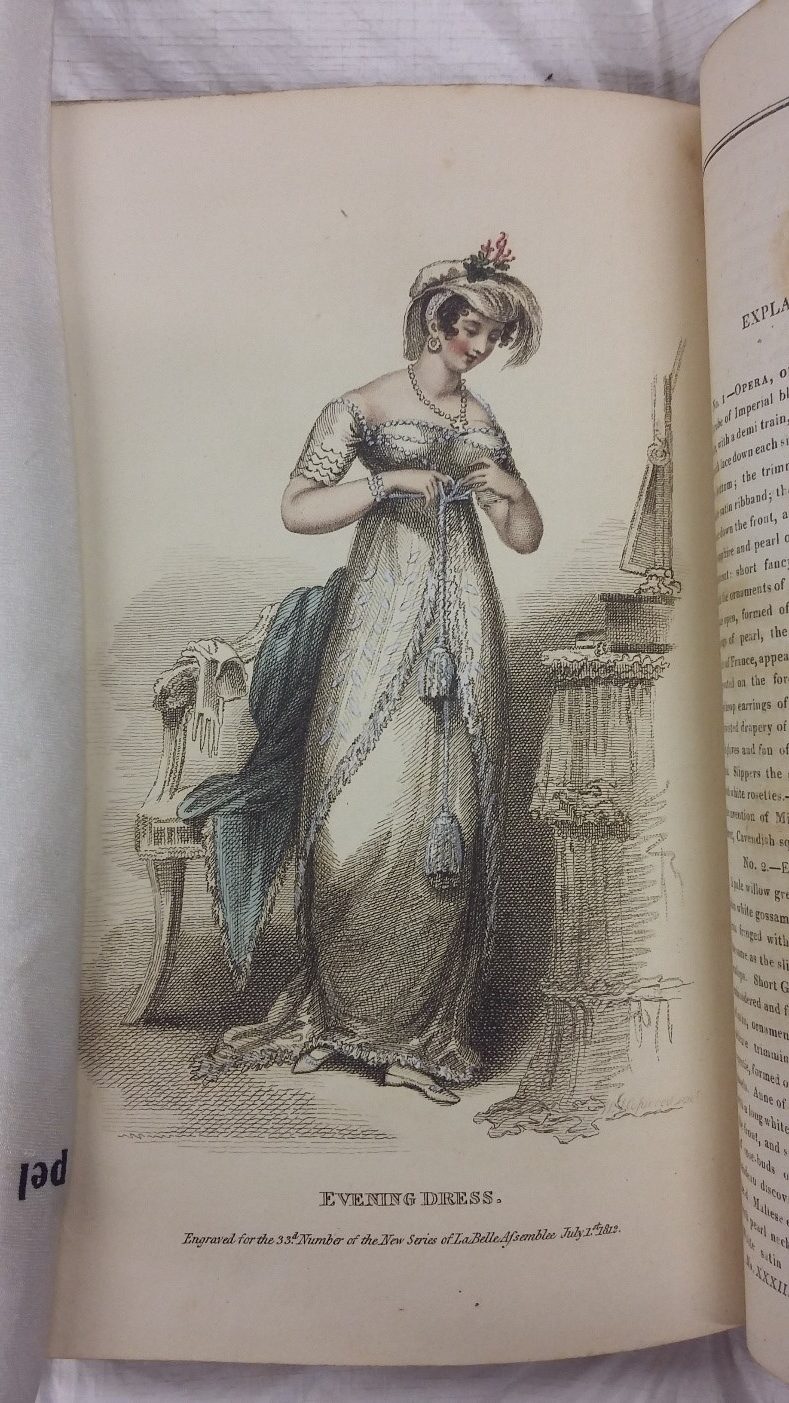

The image that graces this frontispiece is nearly identical to one that was published by The Lady’s Magazine which reported eagerly on Jordan’s first charismatic performance – omitting, in its imagery, the fact that this role, too, featured the adoption of breeches. Thirteen years later, the magazine uses the same terminology to describe the part Jordan plays as Susan Monrose. In doing so, The Lady’s Magazine self-consciously type-casts Jordan as a comedy actress and strengthens its own reputation for consistent and reliable journalism. When La Belle Assemblée published its own series of theatrical biographies in the early nineteenth century, it adapts a famous portrait by John Hoppner of Jordan in 1785 to accompany her memoir. (Fig. 3) The original painting depicted Jordan as the Comic Muse in company of Euphrosyne and a menacing satyr. La Belle Assemblée removes the accompanying characters and conflates Jordan with Euphrosyne in order to function as an illustration of her playing a theatrical part from John Milton’s Comus (1634). As the classical goddess of merriment, this is arguably another incarnation of the comic muse, simply the high-brow equivalent of the country girl. The magazine’s choice is therefore an act of editorial one-upmanship, supporting its own pretensions as much as securing Jordan’s status.

Fig. 3 La Belle assemblée : being Bell’s court and fashionable magazine, addressed particularly to the ladies vol. 10 (Nov 1814) – Classified Sequence (PER AP 4.B31)

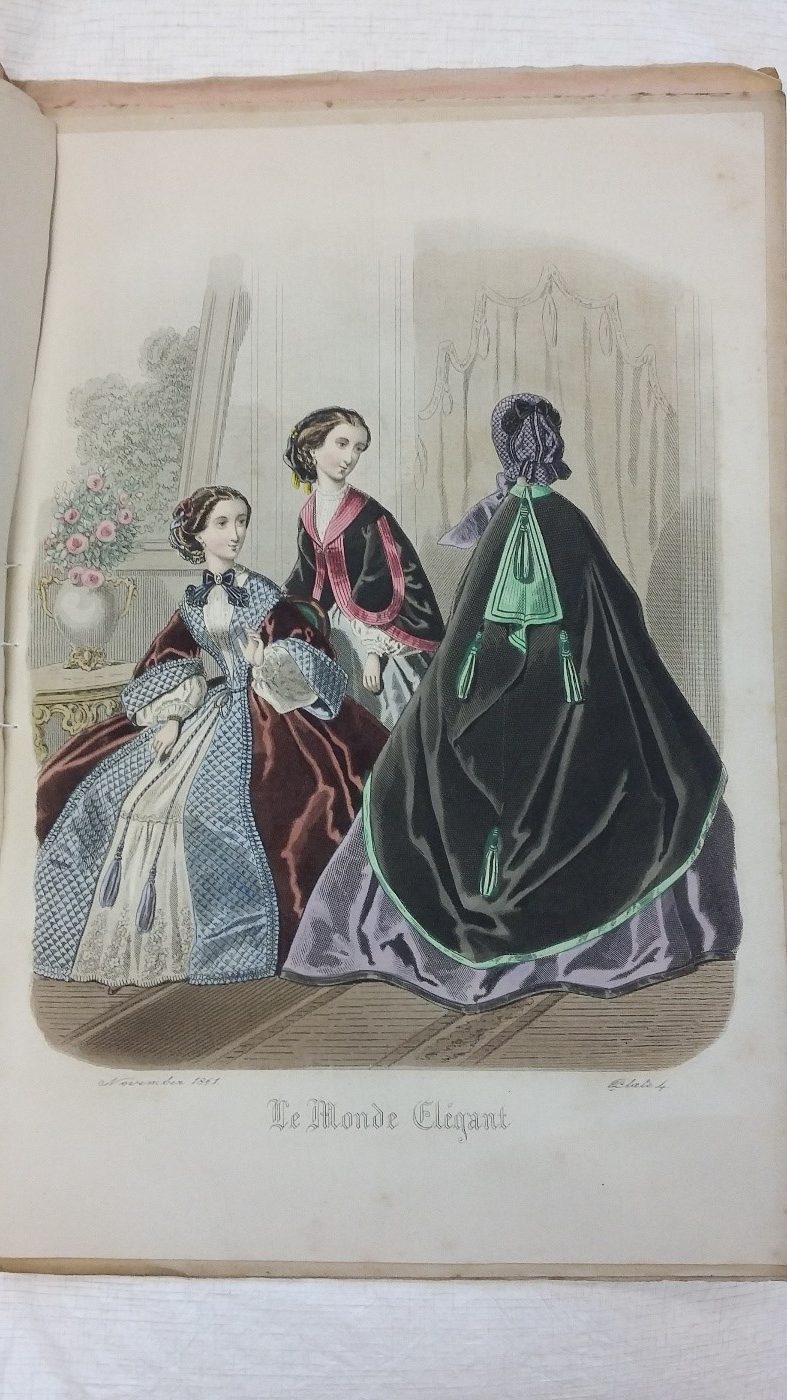

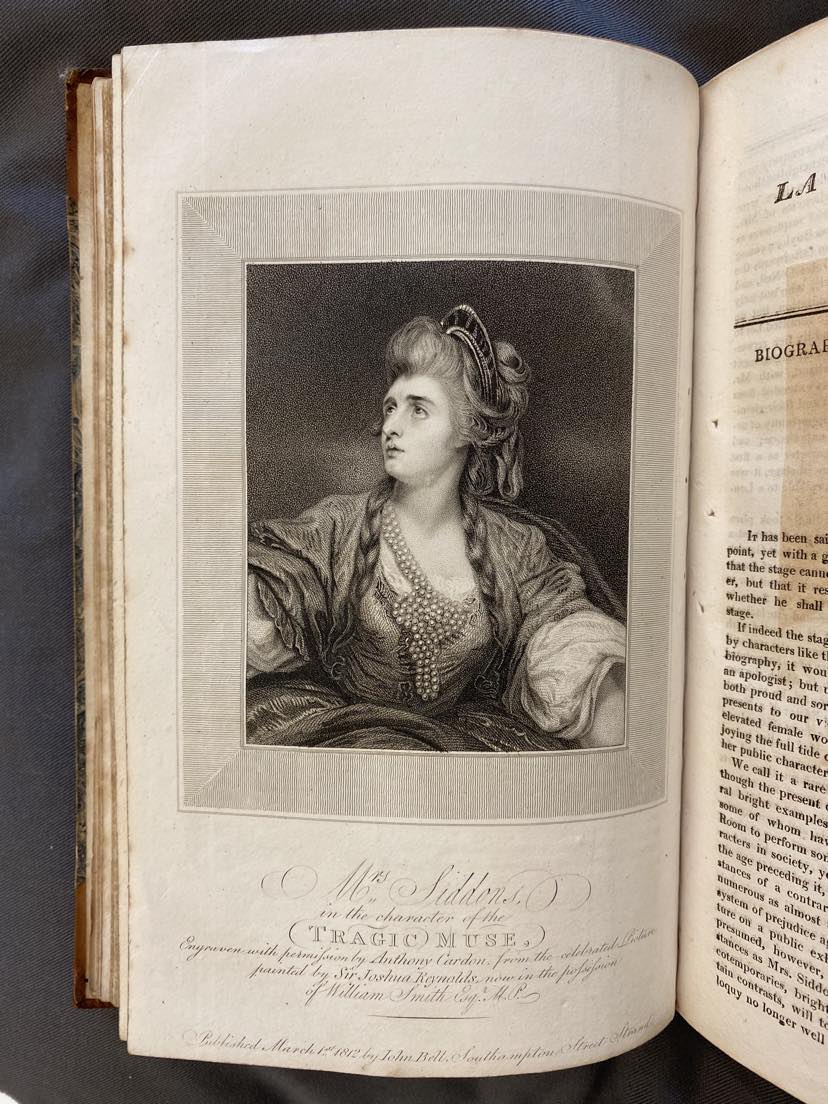

Fig. 4 La Belle assemblée : being Bell’s court and fashionable magazine, addressed particularly to the ladies vol. 5 (Feb 1812) – Classified Sequence (PER AP 4.B31)

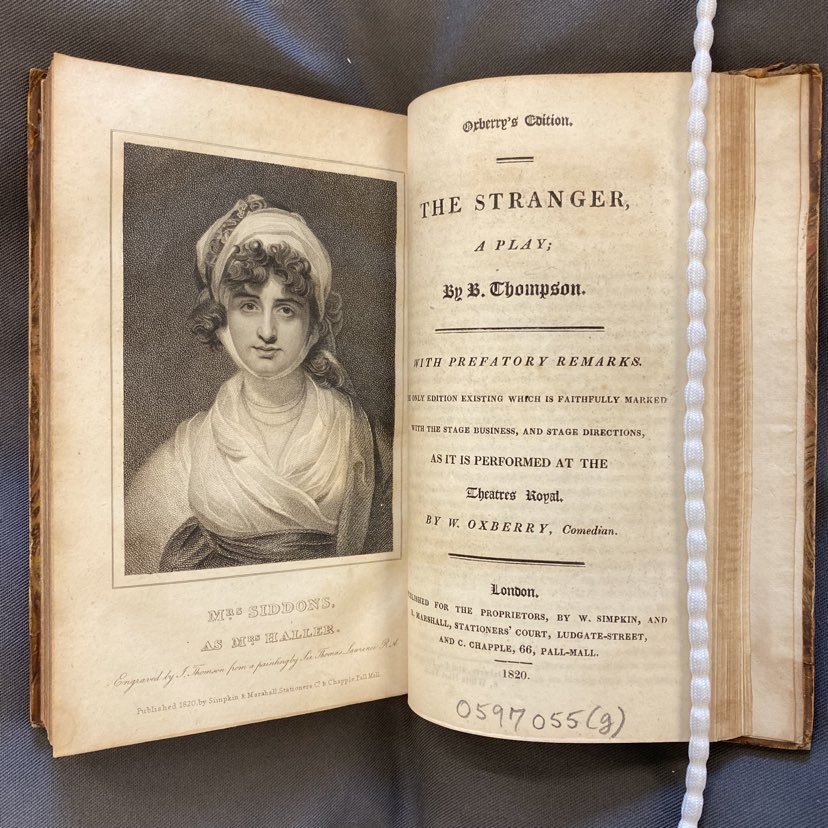

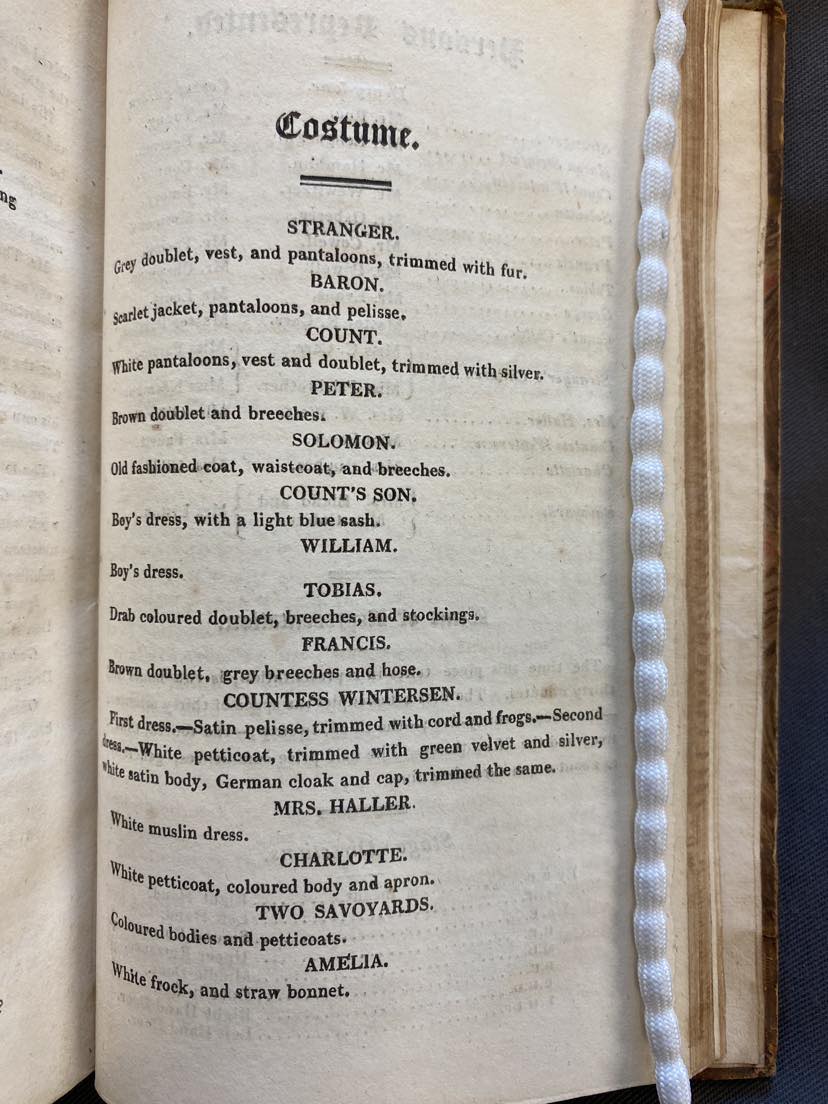

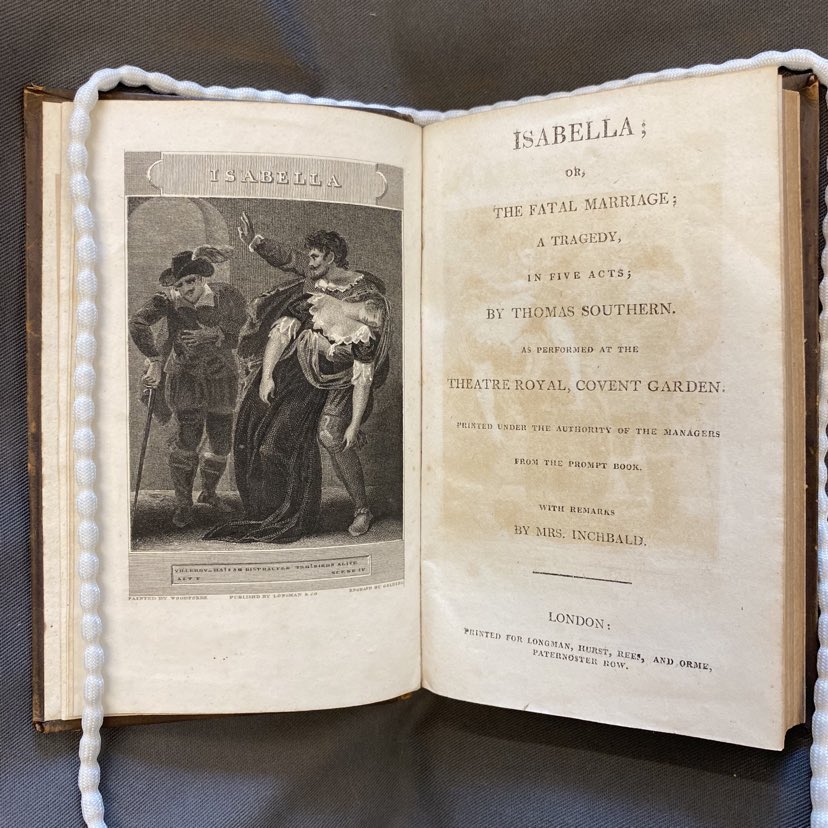

In a neat fait accompli, La Belle Assemblée paired Siddons’ memoir with an engraving of Reynolds’ 1784 portrait of the actress as the tragic muse. (Fig. 4) It is an image designed entirely to evoke homage, and paeans to Siddons are common throughout the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century world of print. Siddons started her career on the provincial circuit before rising to fame in London in 1782 and cultivated a professional profile as maternal tragedienne. She was known to bring her children on stage with her, embodiments of her marital fidelity and mascots of virtue to stave off the satirical press. The Lady’s Magazine for 1798 offers an example of her extensive fandom, printing ‘Lines written on seeing Mrs. Siddons, as Mrs. Haller in “The Stranger,” Friday, 25th of May; and as Isabella, in “The Fatal Marriage,” Monday, 18th, 1798. By Capel Lofft, Esq.’ Mrs. Haller and Isabella were, indeed, two of Siddons’ most famous stage roles, both naturally tragic characters, and Special Collections holds theatrical works that give insight to Siddons’ performance of these parts and to Regency costuming as well. I want to finish this post with my favourite finds: Elizabeth Inchbald’s British Theatre (1806-8) and William Oxberry’s New English Drama (c. 1818-26). These series printed popular plays alongside illustrations and forewords that reflected contemporary productions, including those of The Stranger and Isabella; or, the fatal marriage. In comparing the two (Figs. 5-7) we can see an interesting contrast in theatrical wardrobes, from the white muslin of an unabashed Mrs. Haller to the Van-Dykd velvet of the swooning Isabella. The stage, of course, was (and always will be) a place where contemporary fashions and fanciful costumes vie with each other.