This year marks the 600th anniversary of the death of Richard Whittington, a well-known fifteenth-century Mercer and three times Mayor of London, who was key in shaping civic governance in medieval London. He also served under three medieval kings, Richard II, Henry IV, and Henry V. His legacy and memory has survived the test of time, albeit with a few embellishments along the way (there’s no record confirming that Richard Whittington ever had a cat, for example). Nevertheless, even in the present day, we continue to remember Whittington for he serves as the inspiration for the tale we all know and love, Dick Whittington and His Cat.

Black and white photograph of Dorothy Ward as ‘Principal Boy’ in Dick Whittington, taken at the Whittington Stone (created 1821) at the foot of Highgate Hill, London. Photograph in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

The Story of Dick Whittington and His Cat

The story of Dick Whittington is one of England’s most famous folk tales, harking back to the early modern period, with one of the first fictionalised references to Richard Whittington and his cat being made in a ballad written by Richard Johnson in 1612. The story was adapted into prose form during the later 17th century by Thomas Heywood, who wrote The Famous and Remarkable History of Sir Richard Whittington, and then it was crafted into a puppet play during the 18th century by Martin Powell. As from 1814, the story was further adapted as a staged pantomime, with the first performance starring Joseph Grimaldi as Dame Cicely Suet, the Cook, and later as a tale for children.

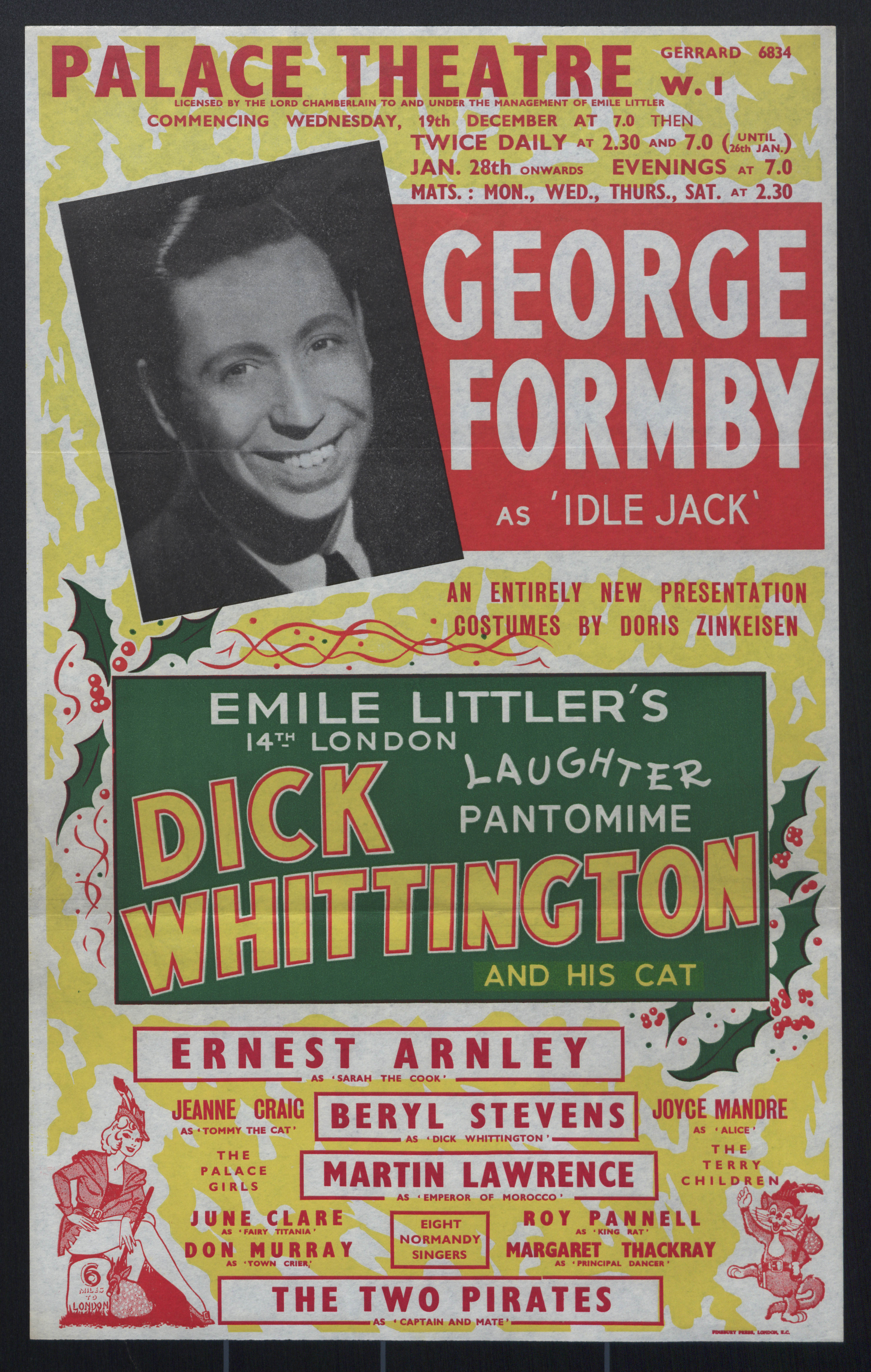

Flyer for a performance of Emile Littler’s Dick Whittington and His Cat at the Palace Theatre in London. Flyer in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

The story that modern day audiences are familiar with tell the tale of an orphan boy, Dick, who ventures to London hoping to make his fortune, believing the streets of London to be ‘paved with gold’. He enters the employment of the merchant FitzWarren, who takes him in, yet Dick finds life as a scullion boy miserable as he is bullied by the Cook and does not enjoy being plagued by rats and mice. It is during this time that he buys his cat, hoping to keep the vermin away. Dick, however, soon ventured his cat to acquire a stake in the cargo ship that was set to sail for north Africa. Nevertheless, when the bullying of the Cook intensifies, Dick runs away yet soon returns after hearing the bells of Bow Church speak to him ‘Turn again Whittington Thrice Lord Mayor of London’.

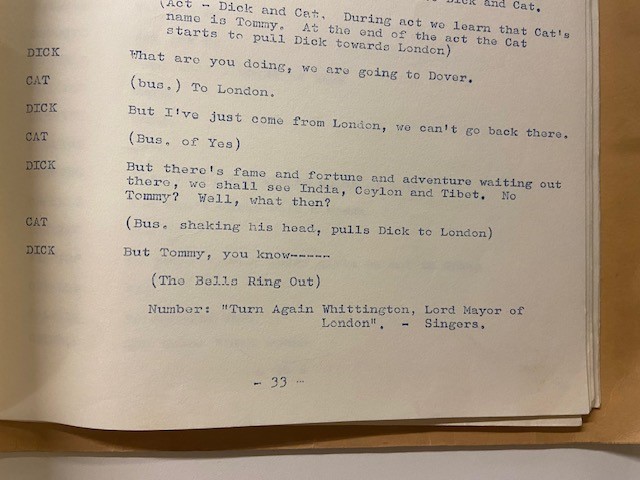

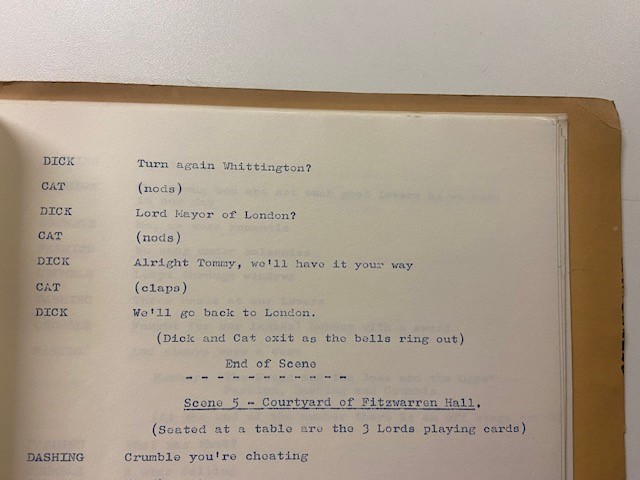

Extract from Scene 4 of the pantomime ‘The Adventures of Dick Whittington’ from a script collection of Clarkson Rose’s. In this scene, Dick hears the bells call out and predict that he will be Mayor of London. This performance took place at the Palace Theatre in Westcliff-On-Sea. Item in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

Extract from Scene 4 of the pantomime ‘The Adventures of Dick Whittington’ from a script collection of Clarkson Rose’s. In this scene, Dick hears the bells call out and predict that he will be Mayor of London. This performance took place at the Palace Theatre in Westcliff-On-Sea. Item in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

Upon his return to FitzWarren’s home, he finds out that he is a rich man. His cat who had formed part of the crew of the vessel that set sail for north Africa was loaned to the King of Barbary as his Palace was overrun with rats. The king was so grateful for the cat’s service, that he paid for the entire cargo and ten times as much for Dick’s cat. From this point onwards, Dick’s fortunes continue to improve by marrying Alice FitzWarren, his employer’s daughter, and becoming Mayor of London three times, just as the bells of Bow Church had foretold.

Where History and Myth Meet

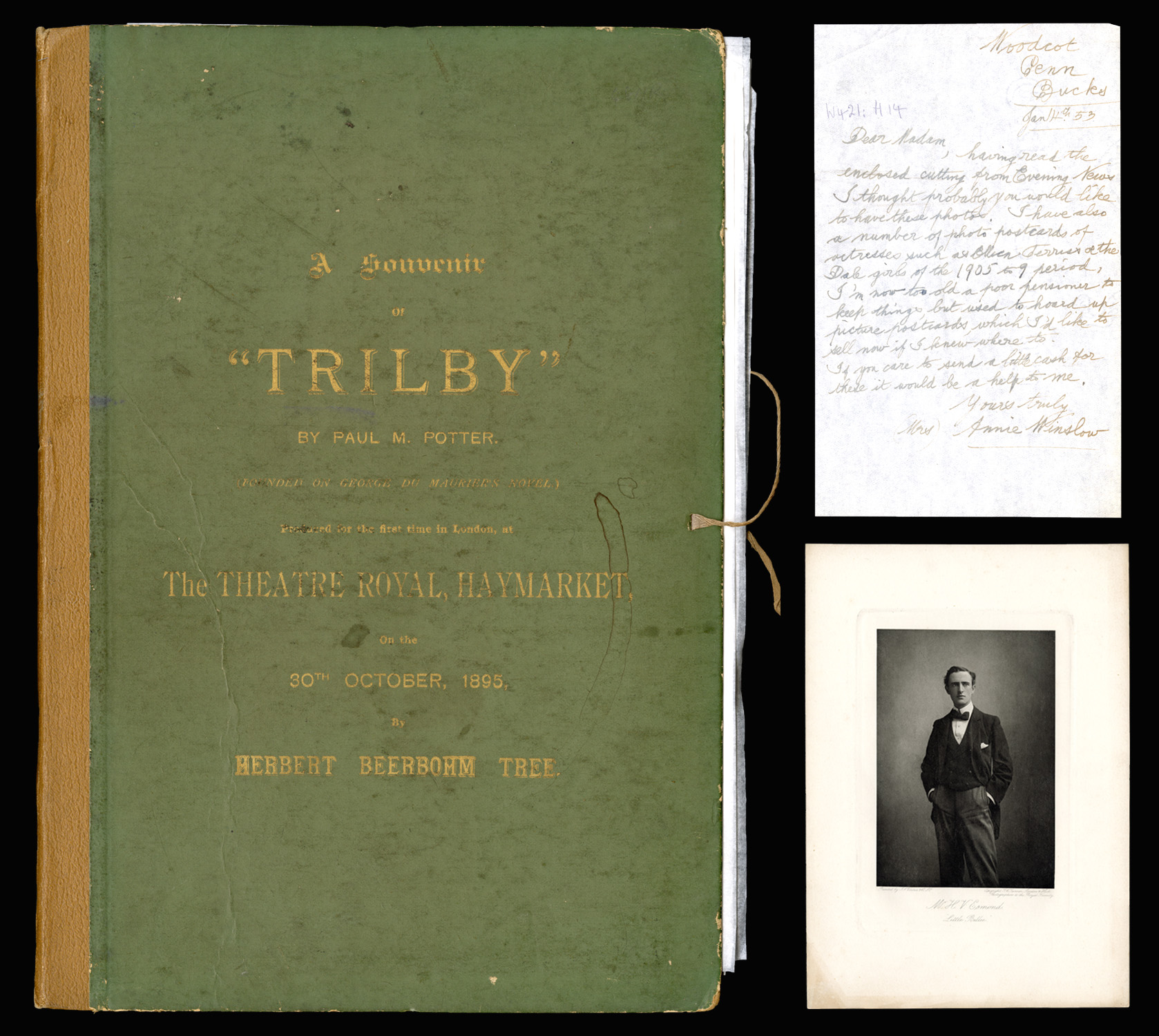

Whilst the story that we recognise has been largely fictionalised, elements of the life of the true Richard Whittington form the basis of the pantomime. Even those responsible for staging the pantomime Dick Whittington, recognised the performance’s historical links to this medieval mayor of London, questioning aspects of the myth surrounding Whittington, such as whether he had a cat and where the origins of this story came from.

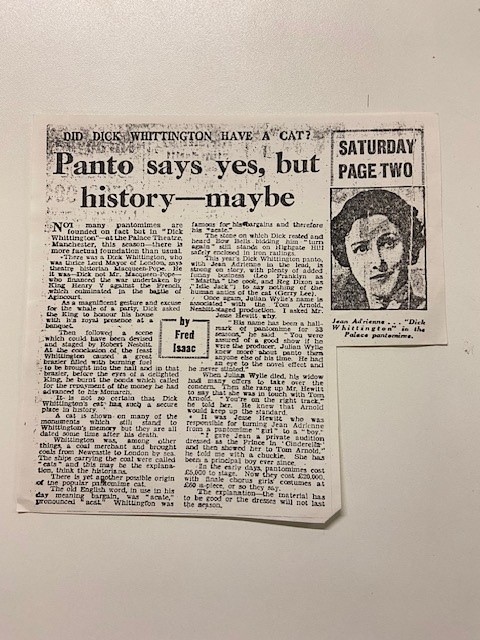

Short article explaining the historical links between the pantomime Dick Whittington to Richard Whittington, mayor of London during the late medieval period. The news article also gives details of the upcoming pantomime starring the Principal Boy Jean Adrienne as Dick Whittington in the upcoming pantomime at the Palace Theatre in Manchester. News cutting in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

These links can be further explored within the source material available for the pantomime Dick Whittington in Special Collections & Archives’ David Drummond Pantomime Collection, which is currently being catalogued after being awarded an Archives Revealed grant from The National Archives.

Travels to London

Central to the story is London as a focal point for the fortunes of Dick Whittington and the real historical figure of Richard Whittington. Like the fictional character Dick Whittington, the real Whittington also came from outside of London. In contrast to his dramatised counterpart, however, Richard Whittington was born in Pauntley, Gloucestershire during the 1350s and did not begin his tale in Lancashire. Whittington’s story was also not a tale of rags to riches. Unlike young Dick Whittington, who was an orphan, Richard Whittington came from a landowning family and was sent to London to undertake an apprenticeship to learn to be a mercer, a type of tradesman that specialised in textiles and luxury goods.

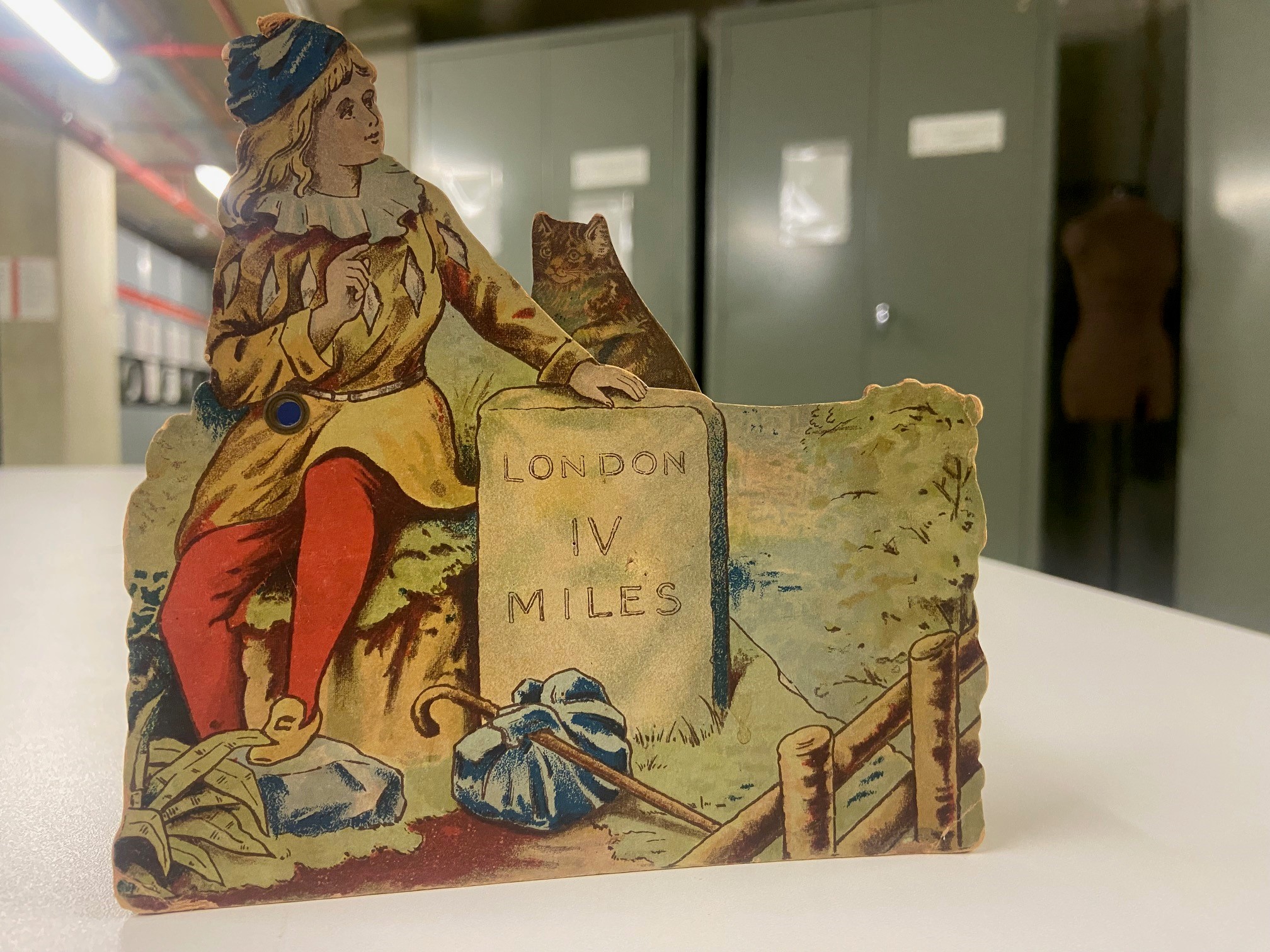

Miscellaneous item showing Dick Whittington and his Cat 4 miles from London. Item forms part of the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

Both Richard Whittington and Dick Whittington also inhabit the same spaces within London. In both the pantomime and in the time period that Richard Whittington lived, both Cheapside and the Guildhall are prominent features of the stories of both of these individuals. Historically, Cheapside was one of the most important streets within London for trade and many of the individual guildhalls were based near this area (and still are to this day). Dick was taken into the home of the merchant Fitzwarren and the real life Richard Whittington himself was engaged in trade because of his profession. It is of no wonder, therefore, that the area known as Cheapside has been incorporated into the pantomime. Similarly, the Guildhall was a place that would have been central to those involved trade. Moreover, the Guildhall was the centre of civic governance and politics, being THE place that mayors of London would have frequented and conducted their business from. The Guildhall and Cheapside were core focal points for Londoners during the medieval period and it is significant that these locations feature in the pantomime of Dick Whittington, showing the clear historic links between both stories. Understanding the importance of London in both their stories is key for audiences to understand that by going to England’s capital, both Whittingtons secured their fortune and created successful careers.

Tradesmen in the Metropolis

Understanding the type of worlds that both Whittingtons inhabit in the city of London is also important in establishing this historical link between these two figures. Dick Whittington may not have been an apprentice to a merchant or artisanal tradesman but he does live in the house of a merchant known as Fitzwarren, who he works as a scullion boy for.

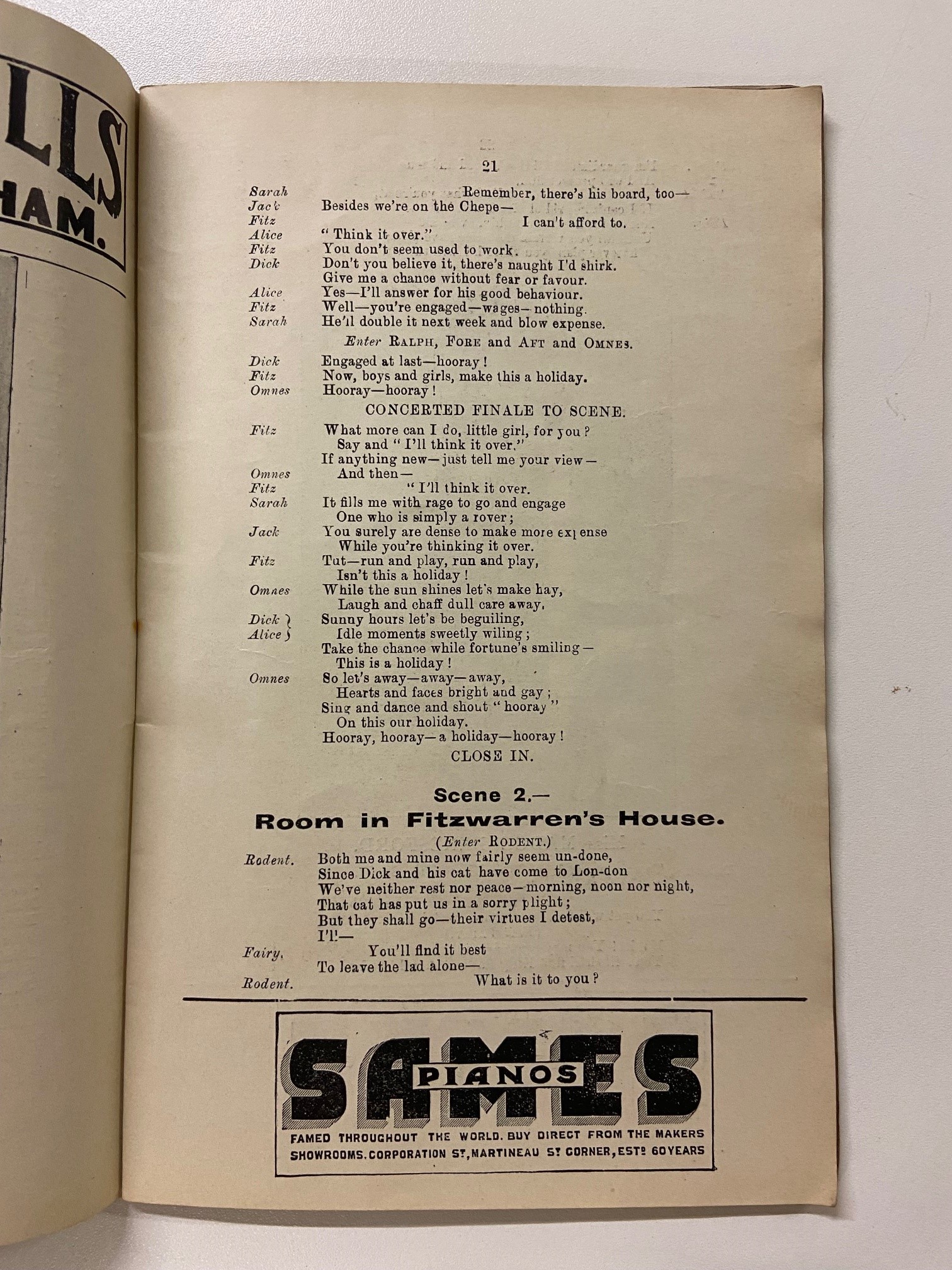

Extract from Scene 2 from a Book of Words of the pantomime Dick Whittington written by Frank Ayrton, produced at the Alexandra Theatre in Birmingham from 1910-1911. It is in this moment that Alderman Fitzwarren agrees to give Dick employment. Item in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

The inspiration for Dick to live in the house of a merchant may come from the work life of the real-life Whittington, who was himself a very successful artisanal tradesman and an established mercer in London by 1379. Whittington also had an upmarket clientele by the 1380s and 1390s, for he sold luxurious goods to customers such as Richard II and other members of the royal family, including John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and Thomas Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester. Despite the change of regime and usurpation of Richard II by the Lancastrian king Henry IV, Richard Whittington continued to prosper and he also sold goods to the new royal family, even supplying goods for the marriages of Henry IV’s daughters, Blanche and Philippa.

Marriage to Alice Fitzwarren

The historical Whittington’s links to the world of trade even influenced the choice of love interest for the character Dick Whittington, for both individuals marry a woman of the same name – Alice FitzWaryn/Fitzwarren.

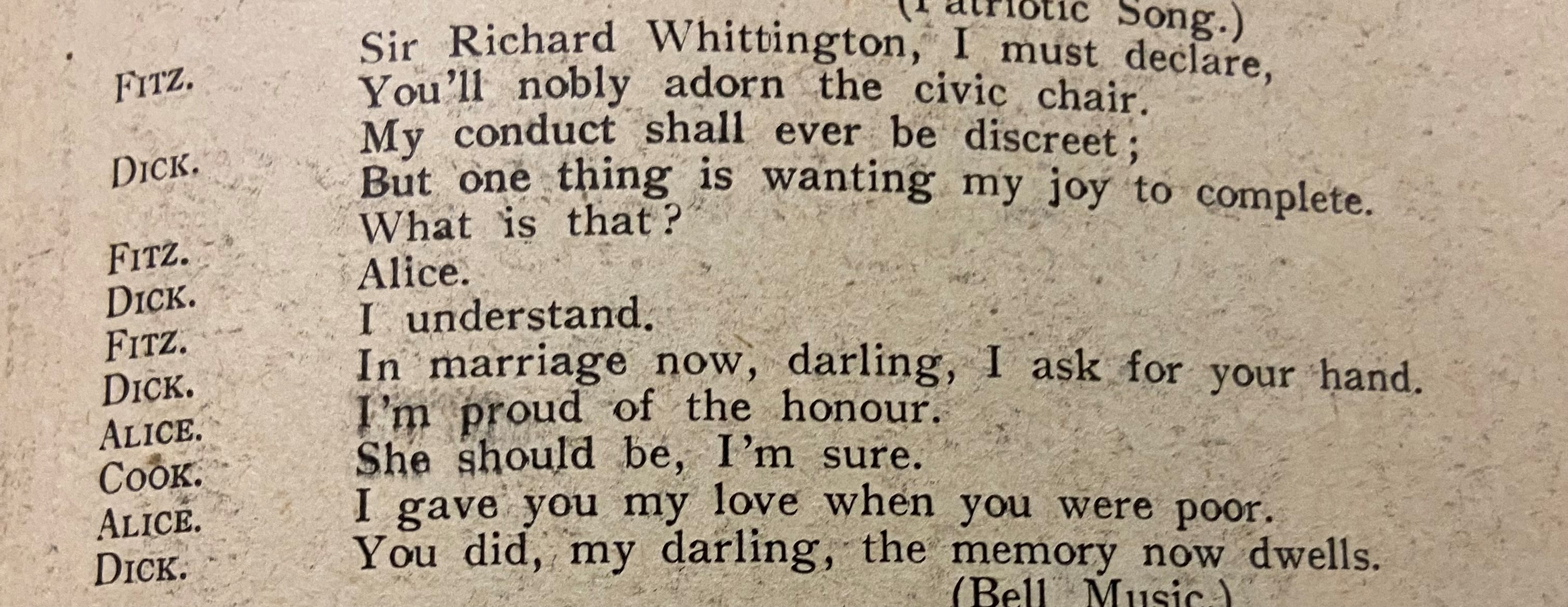

Extract from Scene 12 from a Book of Words for the pantomime Dick Whittington and His Cat written by Newman Maurice, produced at the Brixton Theatre. Now that Dick is Mayor of London, he asks for Alice’s hand in marriage. Item from David Drummond Pantomime Collection

Where the pantomime departs from the true historical narrative, however, is in how that these marriages come about. The historic Richard Whittington married Alice Fitzwaryn, the daughter of Sir Ivo FitzWaryn (clearly the inspiration for Fitzwarren who employs Dick), a landowner in Dorset. Sir Ivo only had daughters and so this was probably an advantageous marriage for Whittington, who married Alice at the age of 48 and who would have inherited certain of Sir Ivo’s estates in Wiltshire and Somerset that would have been passed on to Alice. In contrast, in the pantomime, Alice is the daughter of Dick’s employer, Fitzwarren, and Dick’s love interest throughout, marrying once Dick has made his fortune and is mayor.

Thrice Mayor of London

The clearest link between Richard Whittington and the pantomime character, Dick Whittington, is, of course, the fact that they were both thrice mayors of London.

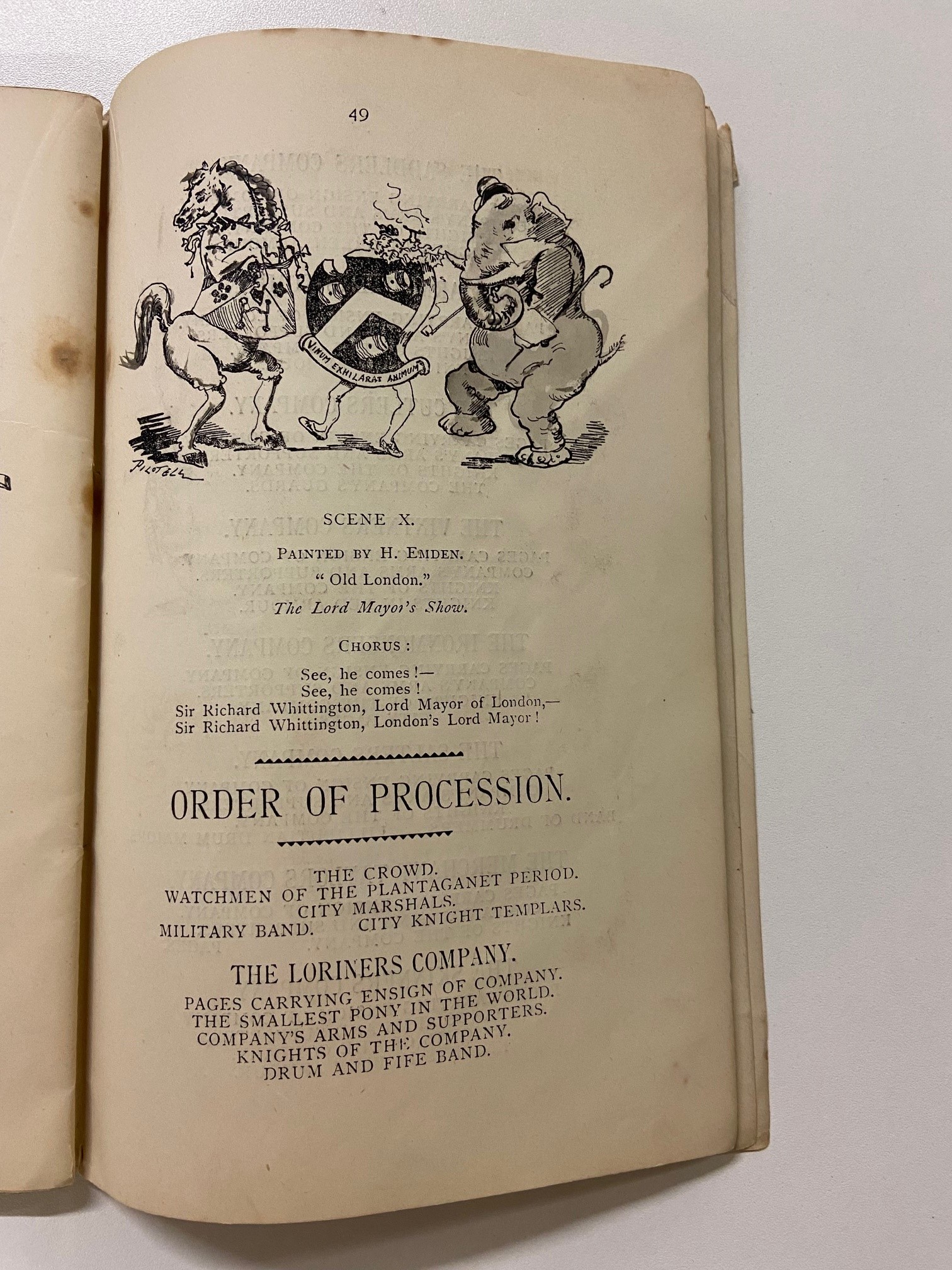

Opening of Scene X in which the Lord Mayor’s Show takes place. Extract is from the Book of Words for Augustus Harris’s Pantomime Whittington and His Cat, produced at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1884-1885. Book of Words written by E. L. Blanchard. Item in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

As mentioned earlier, by the end of the pantomime Dick achieves his destiny and becomes Mayor of London three times. This is in keeping with the fate of the historical figure of Richard Whittington, who was first appointed Mayor of London on 8th June 1397 by Richard II, following the death of Adam Bamme, the previous mayor, on 6th June 1397. What is quite special about the way that Whittington became mayor is that it shows the trust that the King had for him, as Richard II appointed him in this position based on the good relationship that Whittington had cultivated with him. He was then elected mayor by his fellow citizens in 1406 and then again for the third time in 1419.

Charitable Endeavours

Whittington’s charitable nature and philanthropic endeavours are also remembered in the materials available. Once mayor, the pantomime character Dick Whittington’s charitable acts included the building of alms houses, a church, and Newgate Prison. The real Whittington was just as philanthropic, financing a number of public projects, such as drainage systems for the poor. Whittington left in his will £7000 (more than £6 million by modern standards!), which he had drawn up by September 1421, to go towards charitable endeavours. Like Dick Whittington, money went towards the rebuilding of Newgate prison and investing in alms houses, but the historical Whittington also financed the building of the first library in London’s Guildhall and distributed money towards repairing St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

Etching showing Whittington’s Alms Houses on Highgate Hill. Item forms part of the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

Whittington was recognised during his lifetime as being someone who inspired trust and nobly served the city of London. These character traits and commitment to good works certainly seem to have also been integral to the character of Dick Whittington, who follows the historical Whittington’s footsteps in ending his tale by giving back to the City where he was able to forge his path and success. This idea of civic duty and the role of Londoners in upholding these values seems to be preserved in the way that Whittington’s legacy has lived on through the legendary figure of Dick Whittington.

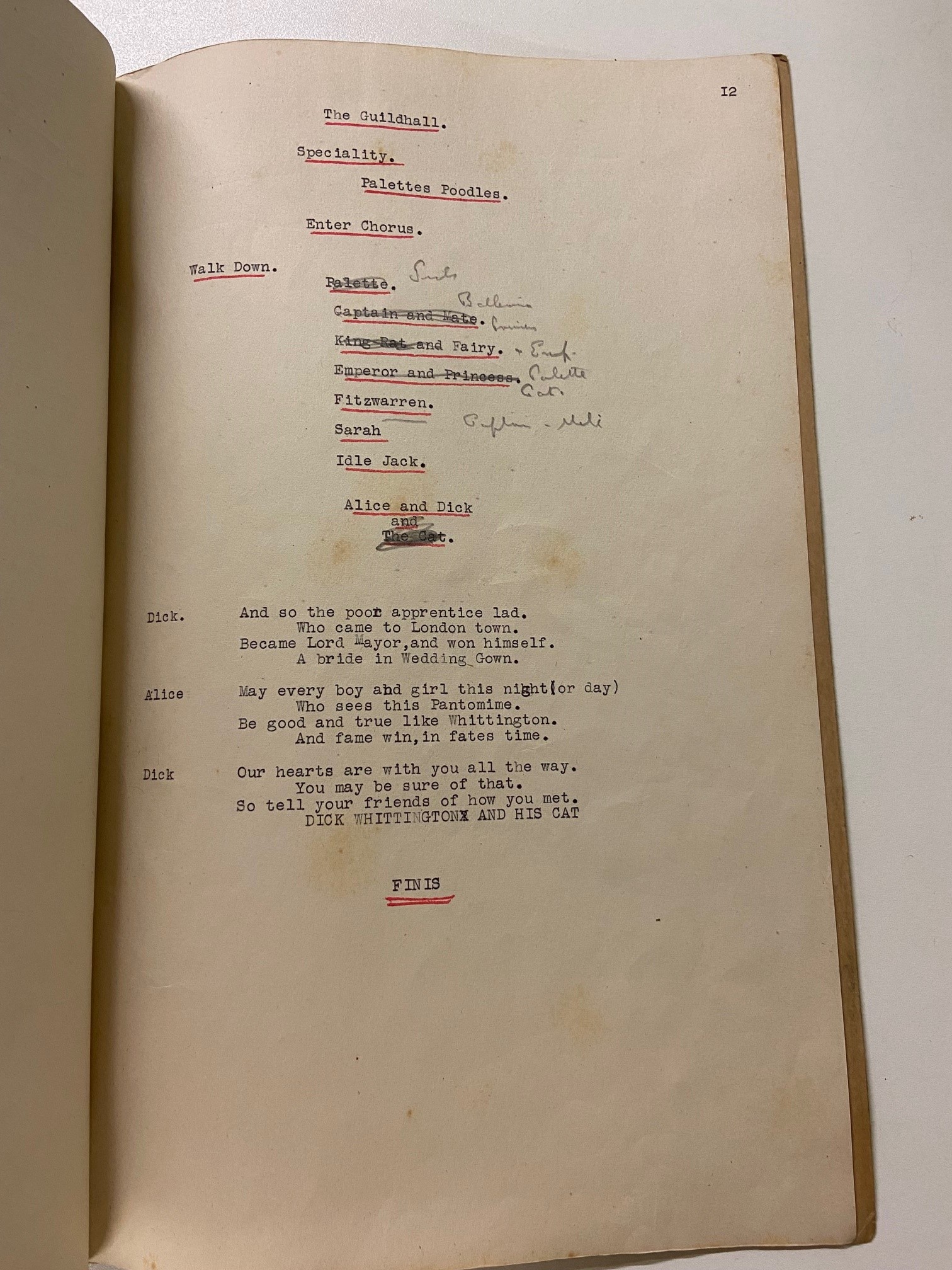

Extract from the final scene in a script for the pantomime Dick Whittington & His Cat, a Christmas pantomime written by Theo Hook in 1948. Before the pantomime ends, Alice reminds ‘every boy and girl this night (or day) Who sees this Pantomime. Be good and true like Whittington’. Item in the David Drummond Pantomime Collection

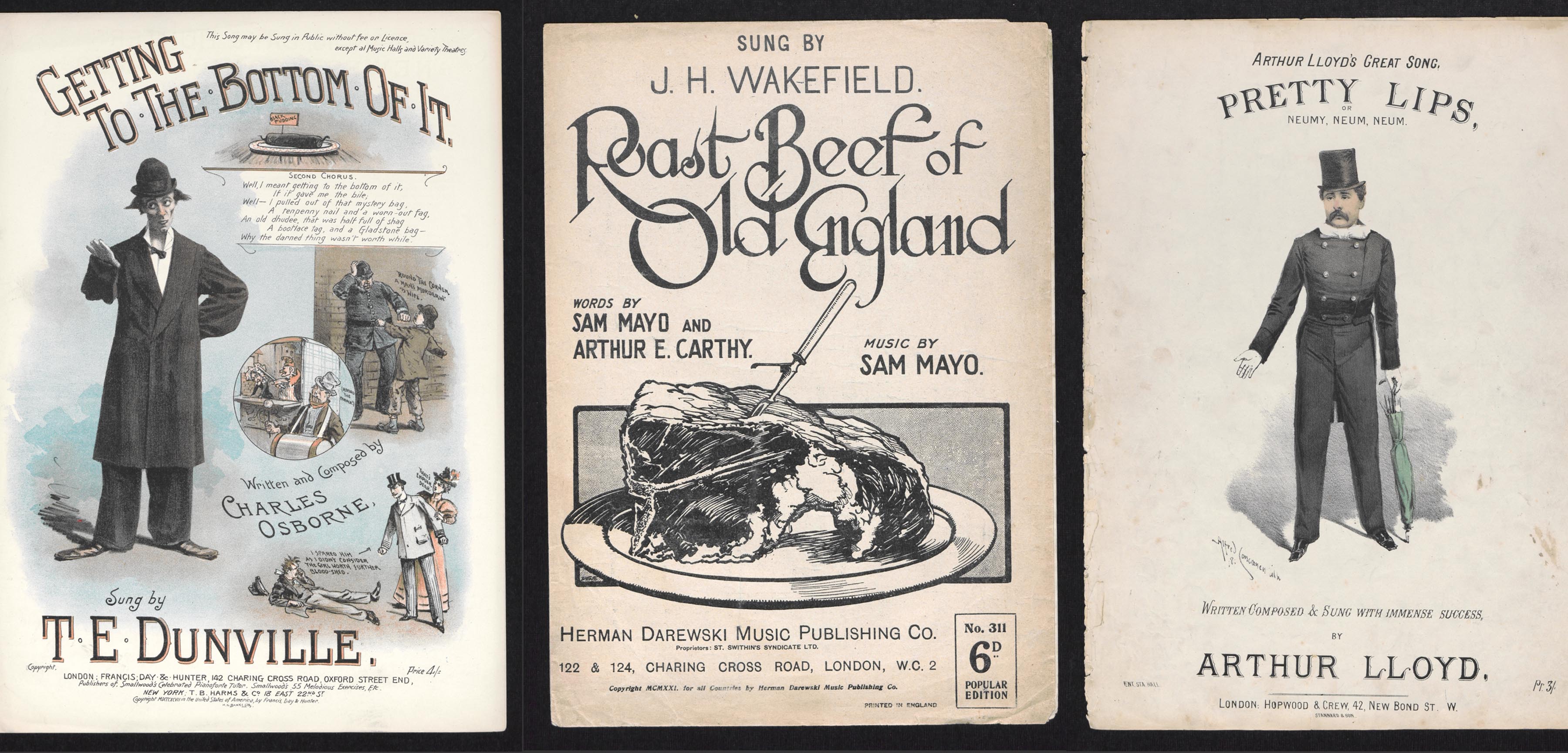

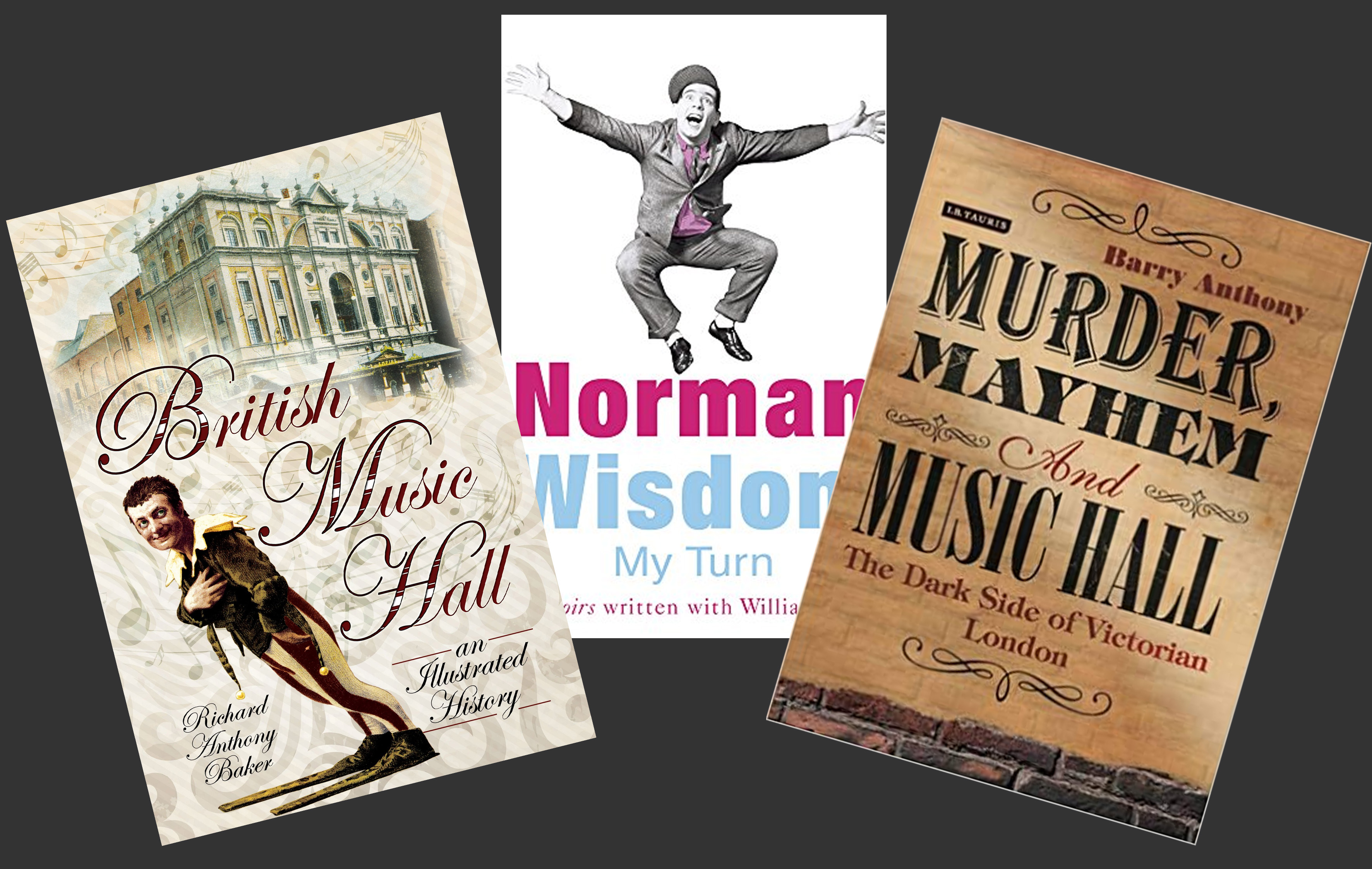

Remembering Whittington on the Stage

Throughout this blog post, you have seen various sources to study the links between the historical figure Richard Whittington and the fictional character of Dick Whittington. The David Drummond Pantomime Collection is a treasure trove for anyone wanting to explore the link between Richard Whittington and his pantomime counterpart Dick Whittington further. From photographs to news cuttings, these materials show us just how many times Dick Whittington appeared on the stage and where, demonstrating interest in the figure and his centrality to the world of pantomime from the Victorian period to the present day. It is a legacy that has survived beyond the fifteenth century and remains in popular memory in our present day.

At Special Collections & Archives, we have a rich collection of pantomime and theatre materials in which the figure of Dick Whittington appears time and time again. Search our catalogue for more and pay us a visit – we’d love to remember Richard Whittington’s legacy with you!