Most of us can trace our love of books to childhood, those formative years in which our imaginations were rampant and our curiosity unquenchable.

Over the course of the last year, I’ve catalogued our Children’s Literature Collection, amounting to 267 books and pamphlets, now readily available to view on our catalogue and consult in our reading room.

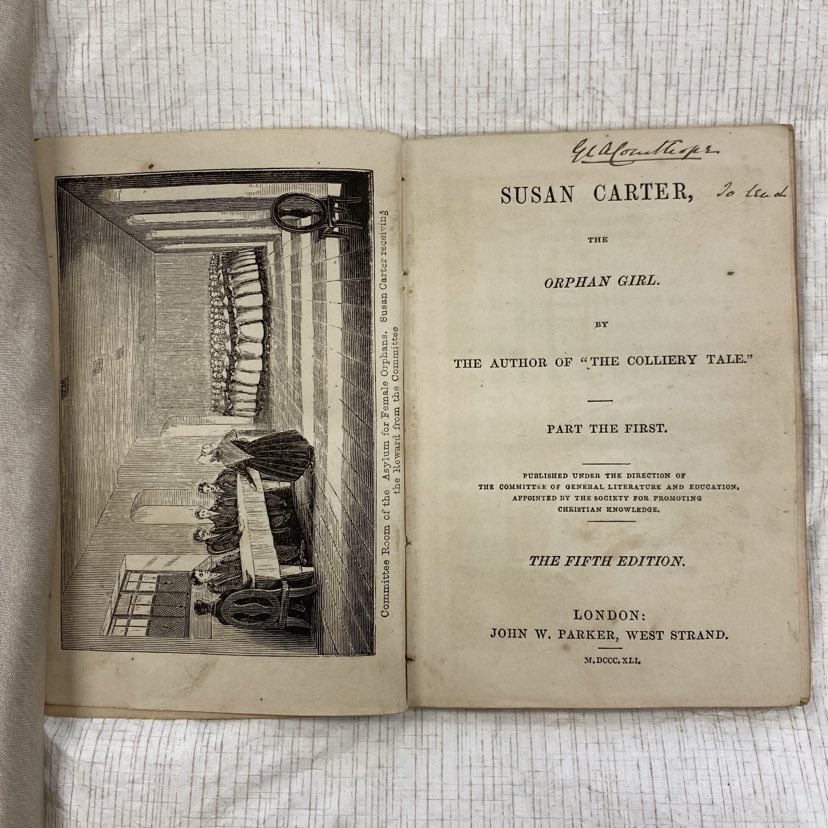

The collection is eclectic in terms of language, genre and aesthetics, including titles in English, German and French, and encapsulating a variety of print technology and literary innovation. The first item I catalogued in the collection dates to 1841, and is notable both for its female authorship and for featuring a disenfranchised heroine: Susan Carter, the orphan girl by Mrs Matthew Plummer. The book must have been popular, for our copy is a fifth edition, and the subject had been increasingly in the public consciousness since the founding of the Foundling Hospital a hundred years earlier. Stories of character overcoming circumstance reoccur throughout the collection, and give canonical context to more famous orphan narratives like those of Oliver Twist and Peter Pan.

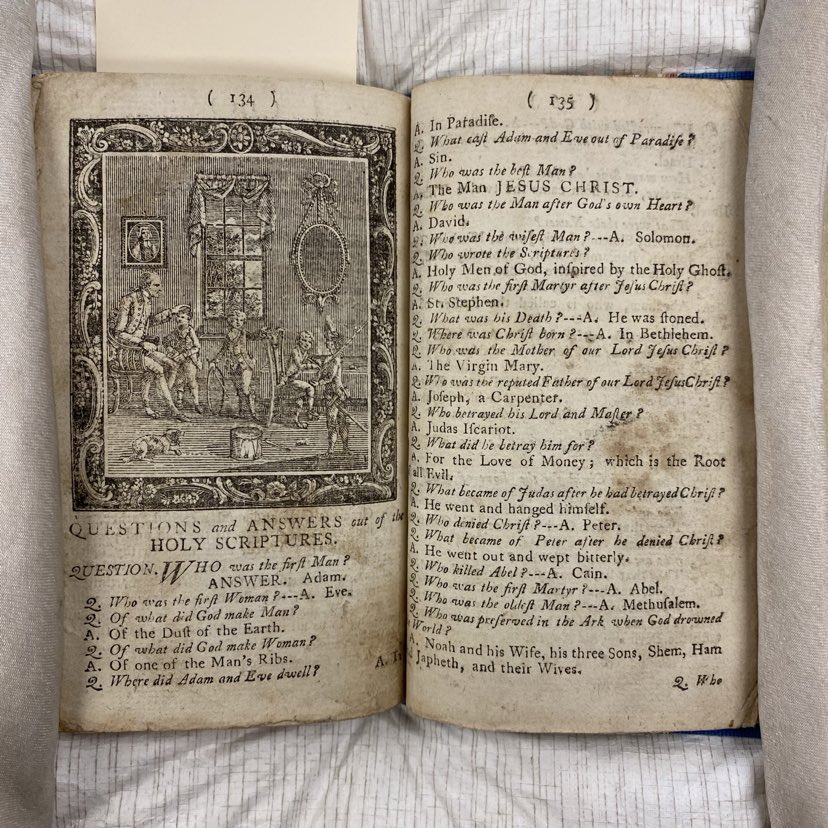

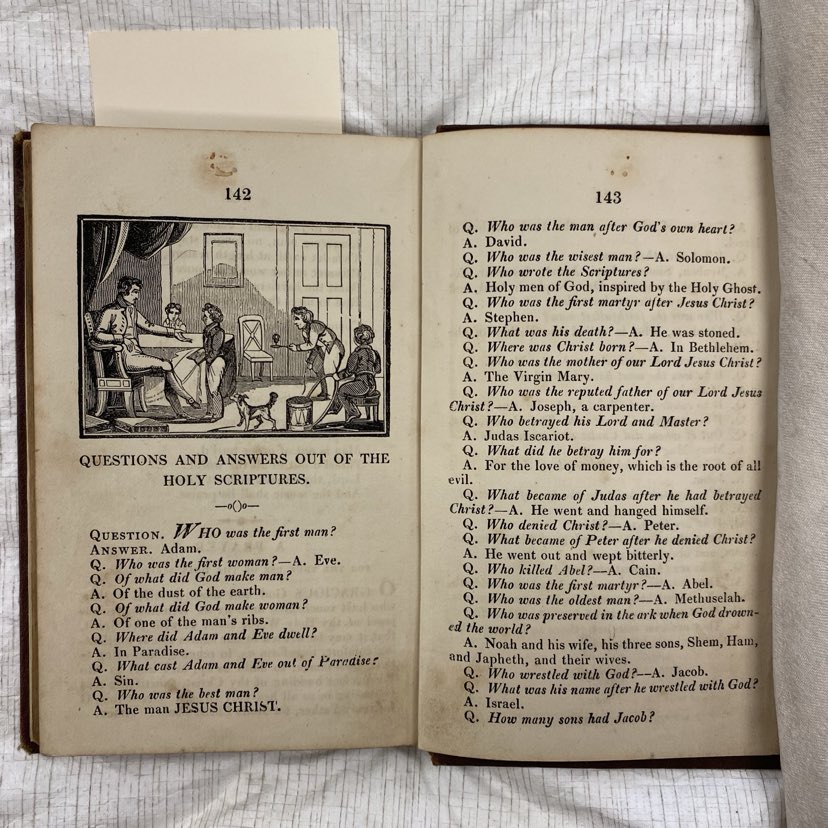

Other earlier women writers are also represented in the collection, notably Hannah More (1745-1833) and Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849). Moralists and educationalists, More and Edgeworth wrote conduct literature, that is stories that revolve around virtue rewarded, deeply grounded in Christian ethics. For them, the purpose of children’s literature was to educate more than entertain, and above all, establish moral literacy. The ultimate example of this must be our hieroglyphic Bibles, in which words are replaced with illustrations that prompt children to fill in the gaps in the text from memory and visual understanding. These abridged versions are strikingly similar despite being published across an eighty year gap, and feature a scripture quiz at the end.

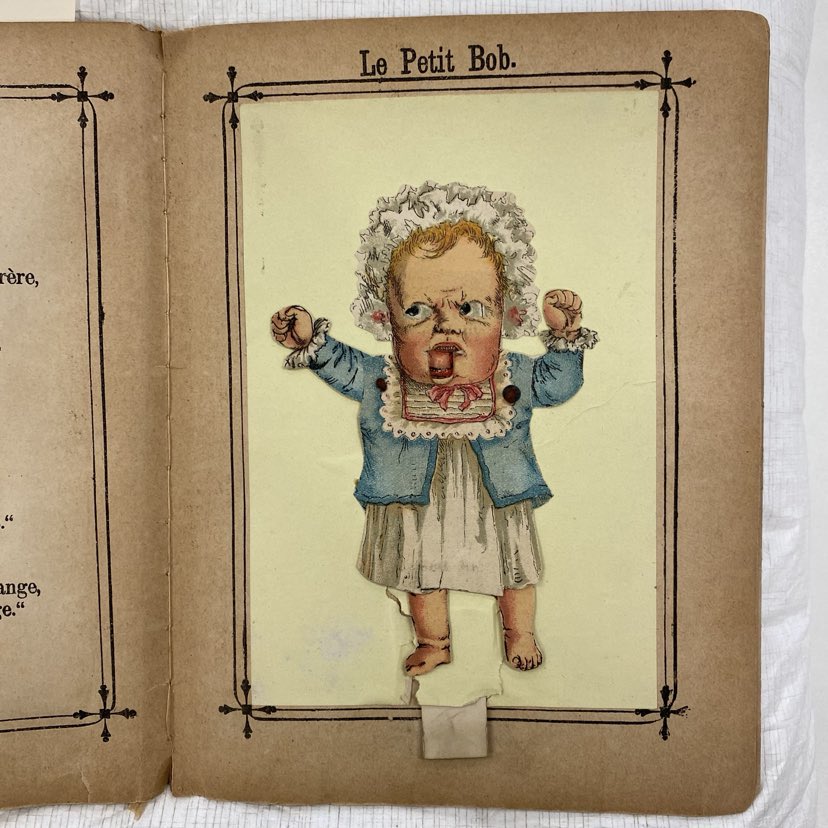

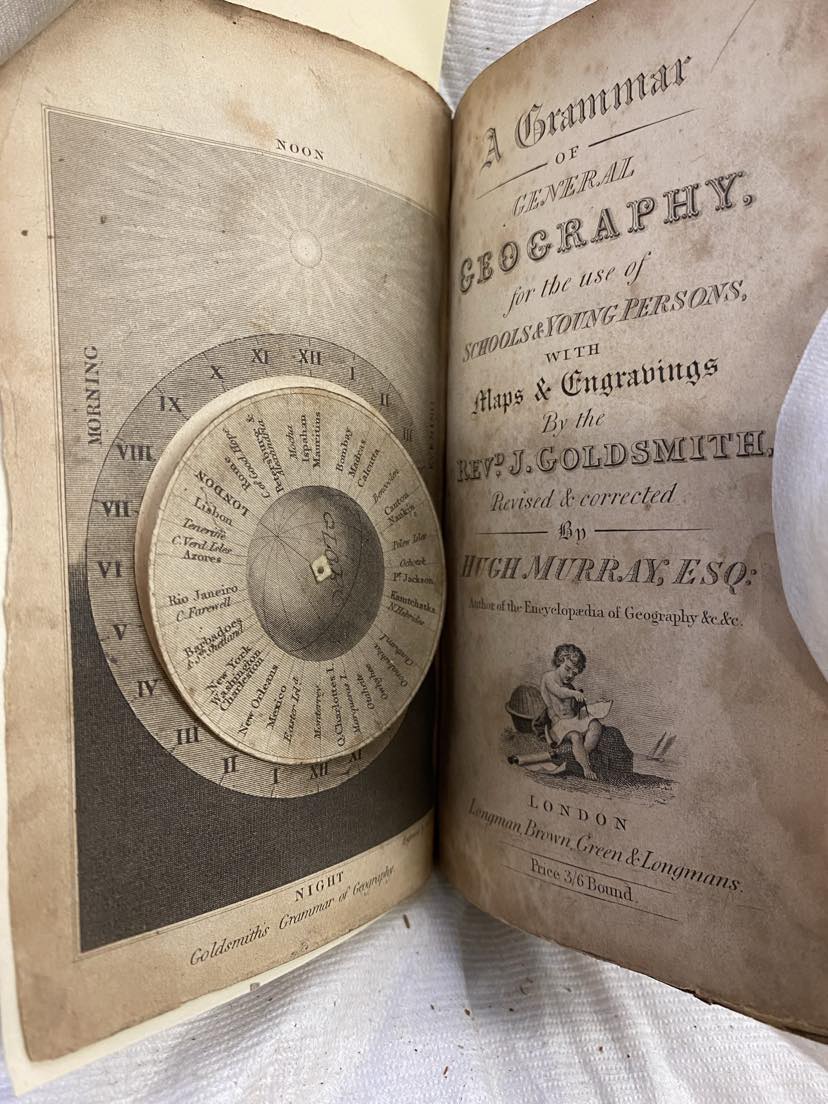

Illustration and novelty of form are frequent features of the collection, for children’s books have ever endeavoured to be visually striking and tactile. Indeed, some of the books are backed onto linen, a practice developed by Routledge in the 1860s, in order to be more durable in the less dextrous hands of small children. Other notable features include paper engineering in the form of pop-up books and books with volvelle frontispieces. Take this macabre and uncanny book, Les Grotesques, which evidences the growing popularity of freak shows in the late Victorian period. And this Grammar of general geography which contains a number of folded maps besides its rotating geographic clock.

Richard Phillips, A grammar of general geography for the use of schools and young persons, with maps and engravings (1842). Children’s Literature Collection.

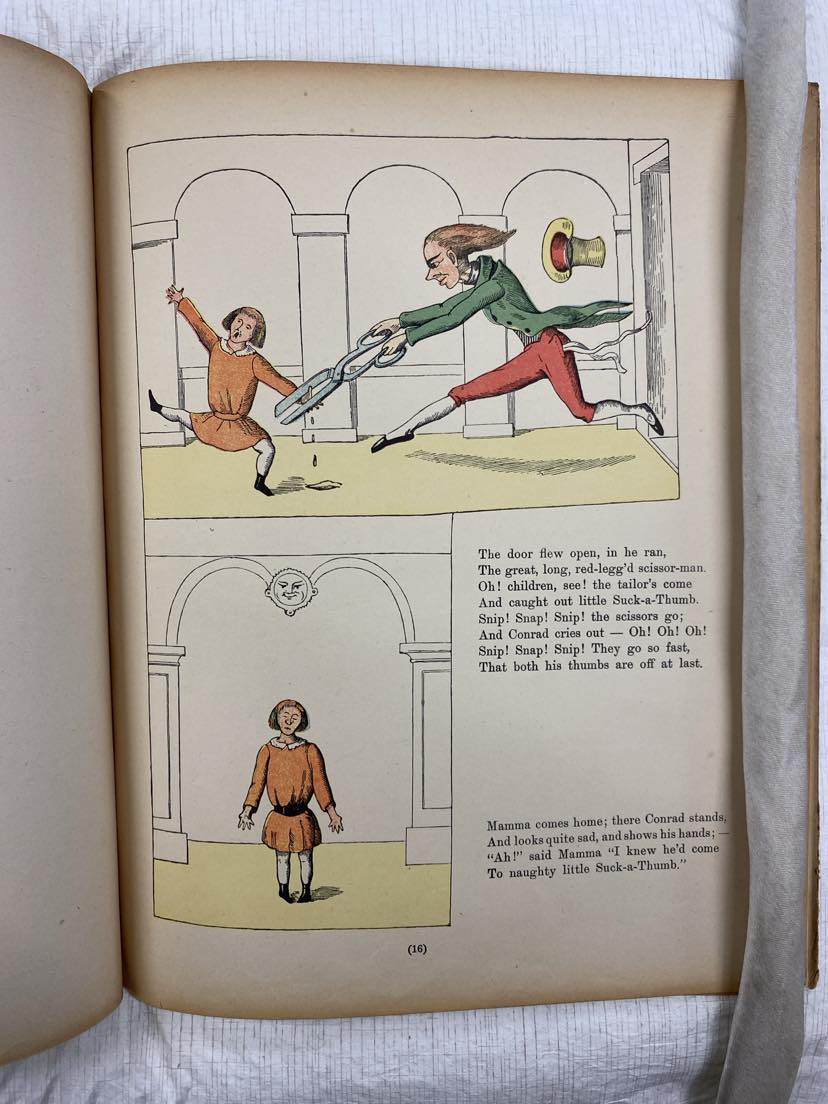

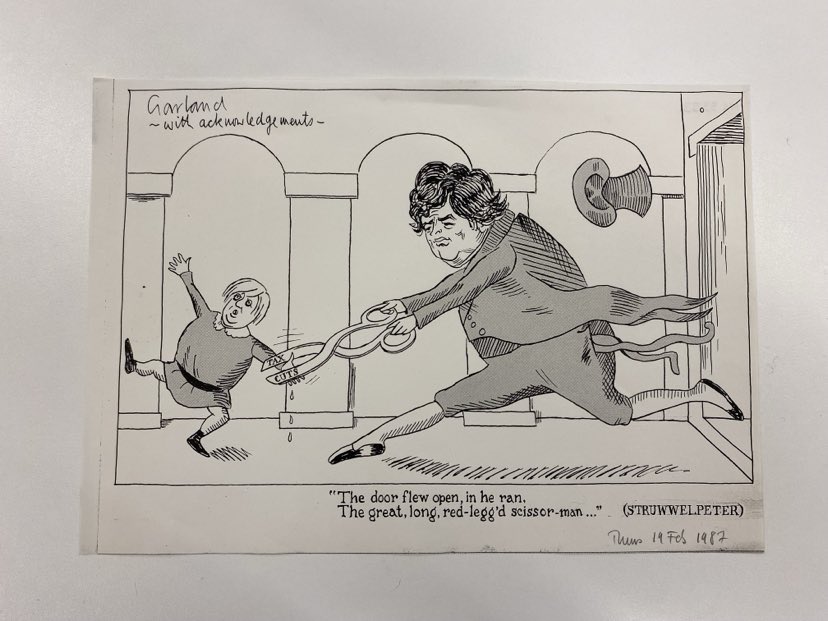

Whilst the collection consists primarily of fairly obscure works, there are some notable classics that are worth mentioning. The most bizarre of these is undoubtedly Struwwelpeter, a selection of cautionary tales derived from the German in which bad behaviour is met with gruesome consequences. It depicts the most shockingly obtuse attitudes to mental illness, including an anorexic that wastes away and a thumb-sucker whose thumbs are chopped by a gargantuan pair of tailor’s scissors. Hoffman’s story of the Scissor-man in particular finds frequent reference in popular culture, including this cartoon by Nicholas Garland.

Heinrich Hoffmann, The English Struwwelpeter : or, pretty stories and funny pictures (1925). Children’s Literature Collection.

Nicholas Garland, “The door flew open, in he ran, The great, long, red-legg’d scissor-man …” (Struwwelpeter) (1987). British Cartoon Archive.

Another significant work in the collection is Edward Lear’s Book of nonsense, for it marks the departure in children’s literature of overt moralising, instead prioritising fancy, fun and foolery. Lear’s Nonsense books popularised the limerick poem and his wordsmithery is an obvious precursor to such playful writers as Lewis Carroll and Roald Dahl. I’ve picked a festive favourite for this blog post, where holly and folly result in melancholy.

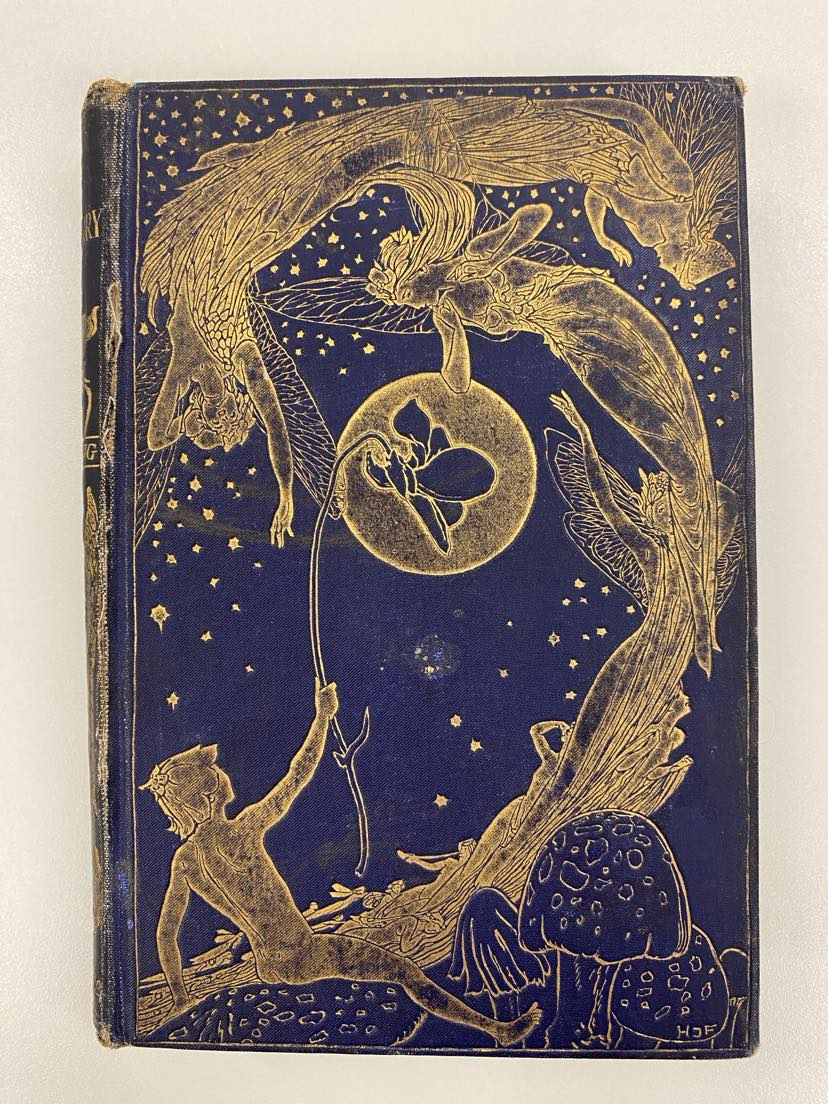

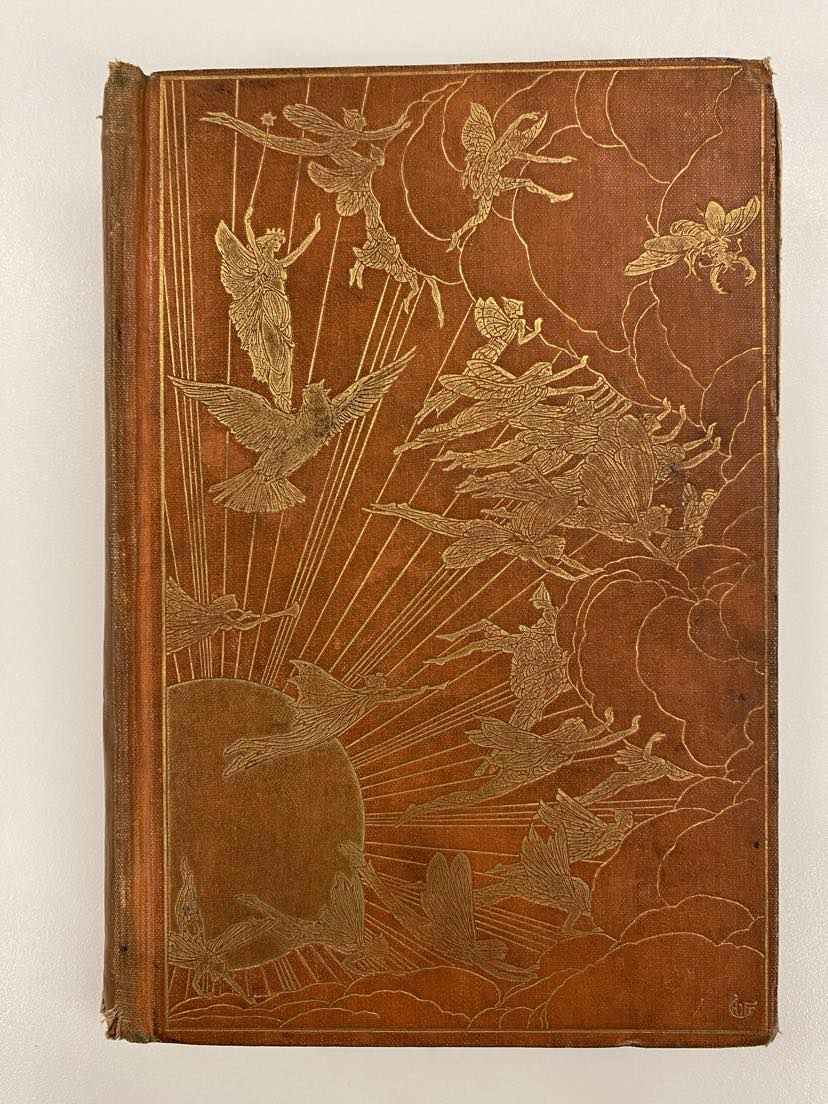

My ultimate favourites in the collection, however, are undoubtedly these coloured fairy books edited by Andrew Lang – or, more accurately, by his wife, Nora. They are significant for their international scope and their Art Nouveau illustrations that strongly associate the fairy tale with Medievalism.

If you are interested in seeing these or other books from the collection, simply place a reservation through Library Search or drop us an email: specialcollections@kent.ac.uk