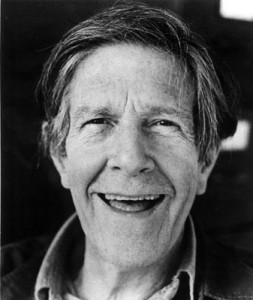

It’s almost hard to believe that this year is not just the centenary of Cage’s birth, but also the sixtieth anniversary of Cage’s noiseless yet sound-rich, notorious masterpiece, 4’ 33’’. Premièred by David Tudor on August 29 in 1952, the piece has gone on to cause controversy wherever and whenever it continues to be performed.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra performed the UK’s first orchestral version of the piece in a concert dedicated to the music of Cage in 2004.

Cage himself reflected on the first performance:

There’s no such thing as silence. What they thought was silence, because they didn’t know how to listen, was full of accidental sounds. You could hear the wind stirring outside during the first movement. During the second, raindrops began pattering the roof, and during the third the people themselves made all kinds of interesting sounds as they talked or walked out.

Cage’s piece draws to the fore the interaction between performer, audience and environment, raising the significance of the non-directed elements present during the piece’s performance; ambient, unintentional noise, aleatoric sounds, events outside of the performer’s control and yet deliberately included as part of the experience. The piece makes room for all those surrounding elements over which the performer has no direct control, and makes them a part of it; it makes us listen not to an arranged series of controlled auditory events, but to whatever sonic incidents happen to occur during that defined time-period during which the piece is ‘performed.’ In fact, the only controlled element of the piece is the time during which these events unfold, defined by the raising and lowering of the piano lid in the piece’s original incarnation. Aside from dictating the beginning and end of each of the three movements, everything else is left to chance.

Tuesday marked the centenary of Cage’s birthday, and there have been events marking the occasion worldwide throughout the year including a special BBC Prom dedicated to Cage’s work (for which the back-up system on Radio 3 had to be turned off, a system which kicks in when it detects ‘dead air;’) yet it’s 4’ 33’’ that remains his most notorious, most thought-provoking piece, and arguably one of the most significant works of the twentieth-century. For a piece with no prescribed sound, its impact continues to resonate still.

Tuesday marked the centenary of Cage’s birthday, and there have been events marking the occasion worldwide throughout the year including a special BBC Prom dedicated to Cage’s work (for which the back-up system on Radio 3 had to be turned off, a system which kicks in when it detects ‘dead air;’) yet it’s 4’ 33’’ that remains his most notorious, most thought-provoking piece, and arguably one of the most significant works of the twentieth-century. For a piece with no prescribed sound, its impact continues to resonate still.