Posted by Sarah

Ann-Marie has very kindly provided the following:

We had a varied and detailed discussion about Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010). Please find our discussion under theme/subject:

Motherhood

Each member found the relationship between mother and daughter disturbing. Firstly, we were unsure whether the mother was a villain or whether we see her through Nina’s interpretation. The film is not always explicit in its depiction of reality (part of its power) but this also leaves for questionable gaps in its reading. A question was raised if we should cast blame on the mother? It seems like a “chicken and egg” scenario and is open to either interpretation. Option A: Mother is to blame, showing the danger of the matriarch. Option B: Nina’s illness has caused an over-protective mother, showing the responsibility placed on the role of matriarch.

Each member found the relationship between mother and daughter disturbing. Firstly, we were unsure whether the mother was a villain or whether we see her through Nina’s interpretation. The film is not always explicit in its depiction of reality (part of its power) but this also leaves for questionable gaps in its reading. A question was raised if we should cast blame on the mother? It seems like a “chicken and egg” scenario and is open to either interpretation. Option A: Mother is to blame, showing the danger of the matriarch. Option B: Nina’s illness has caused an over-protective mother, showing the responsibility placed on the role of matriarch.

The mother’s lack of career did not escape us, particularly because she was supposedly destined to the life that Nina has gained. Two things are suggested here: the mother as self-sacrificing (she gave up her career to have Nina) for the advancement of future women. Or, the continuous replacement of younger women in the entertainment industry. Nina informs us that her mother was already 28, thus past her expiry date. The mother viewed in this sense is a tragic character because she lacks a career, (because of age and children) and is also losing her daughter to the strain of an industry, one that she is acutely aware of.

Another odd occurrence: the moment of Nina’s first sexual experience. Did she imagine her mother in the room during masturbation, or was the mother by her bedside? If the first interpretation is correct then what does this mean? One option could be part of a guilt complex, but should we be more psychoanalytic?

Yet another confusing mother moment occurs when Nina’s mother attempts to throw away the celebration cake. What are we to make of this over-blown reaction? It was noted that Nina is a ballerina and thus most likely on a strict diet so cake would be out-of-bounds, and Nina suggests this very idea to her mother.

Let’s break this down:

- Mother buys a giant cake, but knows Nina will not be able to eat much of it. Is the mother masochistic?

- Nina refuses, as we would expect, so the mother attempts to throw the cake away.

- Nina pleads her to stop, agreeing to eat the cake. The mother is victorious, firmly establishing the power boundaries.

In this scene we can see a guilt complex working in favour of the mother, and if we then connect this to the masturbation scene we could surmise: the mother keeps her in a virginal room made for a young girl, complete with the habitual tucking into bed and brushing of the hair. Nina moves away from the mother’s “ideal” (good little girl) and is struck by an imaginative view of her mother, caused by an inherent guilt complex. These are merely speculations, but what is important to note is how the power boundaries change and evolve.

Female performers/ All About Eve syndrome

A possible fear that is shown through Nina’s character is the dissolution of self. Nina’s submersion into the two roles that she plays begs the question: is a personality lost when one becomes a performer, and if one can lose the self in a part then what is the self, is it something we continually construct? If this Is the case it is no wonder that Nina would fear others, but more importantly the particular danger of other performers. Alternately, we could also consider Nina (or indeed any performer) as an example of the role picked for us and the person we are.

A possible fear that is shown through Nina’s character is the dissolution of self. Nina’s submersion into the two roles that she plays begs the question: is a personality lost when one becomes a performer, and if one can lose the self in a part then what is the self, is it something we continually construct? If this Is the case it is no wonder that Nina would fear others, but more importantly the particular danger of other performers. Alternately, we could also consider Nina (or indeed any performer) as an example of the role picked for us and the person we are.

The performer is presented to us as a fragmented person (Nina, Erica, Beth). The best example of this can be found in:

- Nina – Throughout, often by the use of shots, particularly as she dances. Nina is also is often viewed through another object, such as the window on the subway.

- Beth – First caught in a glimpse through a door, and later becomes both Nina and Beth in the process of self-mutilation.

- Erica (the mother) – her drawings are sharp and disjointed, representing an element of her psyche.

- The obscured view of Nina during the dance sequence in the club could also be noted as the completion of this fragmented self because it is from this that she accepts her duality.

We also noted similar connections to this film and The Red Shoes (Powell and Pressburger, UK, 1948). The film shows a performer that lives her role to such an extent that it becomes her literal destruction.

The uncanny and the double

The use of the double was the reason for the initial interest in the film. In many melodramas we have seen the clear distinctions between good and bad (The Wicked Lady, Leslie Arliss, UK, 1945) and the nature of disguise/hiding true self (Gaslight, Thorold Dickinson, UK, 1940 and George Cukor, US, 1945). Black Swan is no exception, in fact, its use of double and its cause for female stress is explicit. Here are just some of the ways the film shows us that the duality of self is at its core:

The use of the double was the reason for the initial interest in the film. In many melodramas we have seen the clear distinctions between good and bad (The Wicked Lady, Leslie Arliss, UK, 1945) and the nature of disguise/hiding true self (Gaslight, Thorold Dickinson, UK, 1940 and George Cukor, US, 1945). Black Swan is no exception, in fact, its use of double and its cause for female stress is explicit. Here are just some of the ways the film shows us that the duality of self is at its core:

- Half man/ half bird statue

- The use of black and white throughout the film, particularly in décor. Note: the shift between pink/pastel sheets to white and black on Nina’s bed.

- Costume, particularly Nina’s in contrast to Lily.

- The plot mimics the ballet.

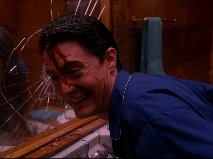

- Use of mirrors and reflections, we view Nina/ Nina’s double/and see other characters.

- Nina replaces a random woman, Beth, Lily, and she also appears in places we least expect, such as the bathtub.

- Shadow manifestation at the end of the Black Swan’s sequence. Note: there are two shadows.

- The performance styles, particularly the sexual prowess and make-up of the Black Swan in contrast with the pastel colours and timid, girl-like performance of Nina.

These are just a few examples, but the message is clear: duality is inherent, and it’s everywhere. Interestingly, the duality causes fear and paranoia at first and then destruction by its acceptance.

Sexuality and gender roles

Purity is seen as a form of weakness. Thomas tells Nina at various intervals to stop being weak and that she seems too reserved, thus, has an inability to lose herself in a good performance. Perhaps most fascinating is Thomas’ mention of Beth. He tells Nina that it is the dark impulses of Beth that makes her perfect, albeit destructive. It seems that the film suggests that a woman finds perfection in accepting her inherent dichotomy. Often the stereotyped woman is the virgin or the whore, and this film challenges those preconceptions as well as challenging the idea of a defined sexuality. Nina experiments with men and has fantasises about women, thus showing the possibility of both a fluid

Purity is seen as a form of weakness. Thomas tells Nina at various intervals to stop being weak and that she seems too reserved, thus, has an inability to lose herself in a good performance. Perhaps most fascinating is Thomas’ mention of Beth. He tells Nina that it is the dark impulses of Beth that makes her perfect, albeit destructive. It seems that the film suggests that a woman finds perfection in accepting her inherent dichotomy. Often the stereotyped woman is the virgin or the whore, and this film challenges those preconceptions as well as challenging the idea of a defined sexuality. Nina experiments with men and has fantasises about women, thus showing the possibility of both a fluid  sexuality as well as a rejection of gender roles. However, the “perfection” that Nina feels she achieves by the end of her performance suggests that it is still not possible for a woman to reach the “ideal fluidity,” instead these women will be destroyed by the pressures put upon them.

sexuality as well as a rejection of gender roles. However, the “perfection” that Nina feels she achieves by the end of her performance suggests that it is still not possible for a woman to reach the “ideal fluidity,” instead these women will be destroyed by the pressures put upon them.

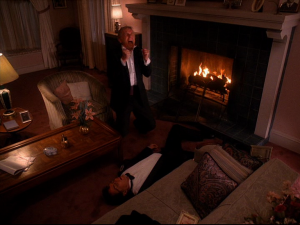

Another comment in regards to women and sexuality was the intriguing fact that women fear each other. This fear seems to derive from the opposing woman’s bodily power. The fear results in jealousy and paranoia, reminding the group of hysteria as a woman’s problem. Note that Thomas finds the notion of another woman trying to steal Nina’s part as ridiculous and he is almost unaware of the pain and stress caused by the decline of Beth’s career.

Please comment further to continue the discussion on this interesting film.

You can log in to do so, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk

Many thanks to Ann-Marie for choosing such a thought-provoking film, providing an interesting introduction and the above excellent summary of our discussion.