Our discussion on the film covered: its melodramatic aspects and the horror genre; related matters of the gothic: the house and the film’s women in peril; Margaret Lockwood’s screen image; Dirk Bogarde’s screen image; Bogarde’s wider role in the film’s production.

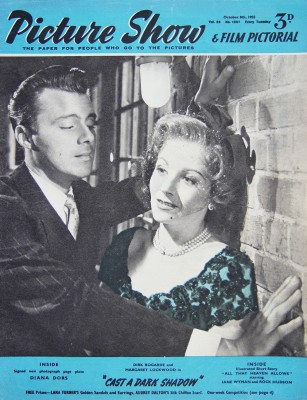

We began by considering Cast a Dark Shadow’s relationship to melodrama, a label it was assigned in some contemporary reviews. It is the only genre mentioned in British fan magazine Picture Show’s brief review (8th October 1955, p. 10). Picturegoer magazine provided more detail, assessing that the film had ‘little mystery, some suspense, but plenty of spirited melodrama’ (17th September 1955, p. 21). We agreed that the fact that Teddy Bare’s (Dirk Bogarde’s) villainy was evident from almost the outset meant that mystery and suspense were subjugated to melodrama. This melodrama mostly takes the form of changing rhythm: less exciting scenes are punctuated by moments of action. Confounding expectations of horror also occurs. The  film opens with a piercing scream from, and a look of terror on the face of, Molly Bare (Mona Washbourne). This is soon revealed to be in response to a ghost train ride, rather than a real terror threat, and is followed by Molly and Teddy’s quiet discussion in a quaint seaside tea room.

film opens with a piercing scream from, and a look of terror on the face of, Molly Bare (Mona Washbourne). This is soon revealed to be in response to a ghost train ride, rather than a real terror threat, and is followed by Molly and Teddy’s quiet discussion in a quaint seaside tea room.

We noticed that the film did not rely on coincidence to the same extent as many melodramas we’ve screened. In fact, melodrama was supplied in the realistic and psychologically well-motivated relationships between the characters. Our consideration of characters led us to contrast Teddy (the irredeemable villain) to his wives, and other women, in the film (his potential victims). Viewing these women as women in peril connects it to the Gothic – a matter the melodrama research group has an interest in (see the blog’s gothic tag: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/tag/gothic/ ).

This was supported by another key theme of the Gothic – the old dark house – being present. Much of the action takes place in the Bares’ large isolated house. This is perhaps unsurprising as the film is Janet Green’s adaptation her own stage play which ran in London from 1952-1953. The filming adds other important details. The house’s location is visually connected to peril by a sign noting the ‘dangerous’ hill which foreshadows the film’s later action. Furthermore, Bare’s first wife, Molly, is killed by her husband in this house, and he makes use of a domestic appliance (a gas fire) to this end. The cinematography of this scene is particularly atmospheric. Molly is pictured drunkenly dozing in a chair in the foreground of the shot while Teddy enters through the patio doors in the shadowy background.

This was supported by another key theme of the Gothic – the old dark house – being present. Much of the action takes place in the Bares’ large isolated house. This is perhaps unsurprising as the film is Janet Green’s adaptation her own stage play which ran in London from 1952-1953. The filming adds other important details. The house’s location is visually connected to peril by a sign noting the ‘dangerous’ hill which foreshadows the film’s later action. Furthermore, Bare’s first wife, Molly, is killed by her husband in this house, and he makes use of a domestic appliance (a gas fire) to this end. The cinematography of this scene is particularly atmospheric. Molly is pictured drunkenly dozing in a chair in the foreground of the shot while Teddy enters through the patio doors in the shadowy background.

It is also revealed that the house was the reason Molly and Teddy first met. He worked for the estate agent who came to value the house, and indeed the house the only item Molly left him in her first will. Teddy also acts as his own letting agent. He uses the house as a reason for the woman he has lined up to be the next Mrs Bare, Freda (Margaret Lockwood), to visit. When Molly’s sister Dora arrives, incognito as Charlotte Young (Kay Walsh), Teddy takes it upon himself to show her local houses she may be interested in buying. The extended scene of Teddy being confronted by ‘Charlotte’ also occurs in the house. ‘Charlotte’ realises that counter-intuitively she is safer in the house: because of what happened to her sister, Teddy would find it very difficult to explain away another dead woman in his house.

It is also revealed that the house was the reason Molly and Teddy first met. He worked for the estate agent who came to value the house, and indeed the house the only item Molly left him in her first will. Teddy also acts as his own letting agent. He uses the house as a reason for the woman he has lined up to be the next Mrs Bare, Freda (Margaret Lockwood), to visit. When Molly’s sister Dora arrives, incognito as Charlotte Young (Kay Walsh), Teddy takes it upon himself to show her local houses she may be interested in buying. The extended scene of Teddy being confronted by ‘Charlotte’ also occurs in the house. ‘Charlotte’ realises that counter-intuitively she is safer in the house: because of what happened to her sister, Teddy would find it very difficult to explain away another dead woman in his house.

A direct reference to Bluebeard’s chamber reinforces the film’s gothic connections. Freda (Margaret Lockwood) persuades the housemaid Emmie (Kathleen Harrison) to give her access to Molly’s bedroom which has been kept locked since her death. As she enters the room, Freda says it’s a ‘regular Bluebeard’s chamber’, and quips that if Teddy had ‘any more wives I’d have had to sleep in the bathroom’. This points to Freda as surprisingly well-informed about the gothic for a gothic heroine. We also noted that there was no real reason for Teddy to keep Molly’s bedroom locked; unlike the original Bluebeard he was not hiding his late wife’s body there. This led us to ponder whether it was through guilt or regret. Teddy seemed fond of Molly, but the fact that he still blamed her for misleading him about her will – for thinking the change would benefit Dora and not him – suggests that the room is perhaps sealed precisely so that connection to the gothic Bluebeard tale can be remarked upon.

A direct reference to Bluebeard’s chamber reinforces the film’s gothic connections. Freda (Margaret Lockwood) persuades the housemaid Emmie (Kathleen Harrison) to give her access to Molly’s bedroom which has been kept locked since her death. As she enters the room, Freda says it’s a ‘regular Bluebeard’s chamber’, and quips that if Teddy had ‘any more wives I’d have had to sleep in the bathroom’. This points to Freda as surprisingly well-informed about the gothic for a gothic heroine. We also noted that there was no real reason for Teddy to keep Molly’s bedroom locked; unlike the original Bluebeard he was not hiding his late wife’s body there. This led us to ponder whether it was through guilt or regret. Teddy seemed fond of Molly, but the fact that he still blamed her for misleading him about her will – for thinking the change would benefit Dora and not him – suggests that the room is perhaps sealed precisely so that connection to the gothic Bluebeard tale can be remarked upon.

It is significant, however, that Freda does not suspect her husband of killing his first wife or of plotting to kill her. This is unusual when compared to most gothic film narratives. For example, in both versions of Gaslight (1940, UK, Thorold Dickinson and 1944, US, George Cukor) as well as Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) the heroine increasingly comes to suspect her husband. Cast a Dark Shadow diverges from Rebecca and Suspicion since Teddy’s murderous intentions are clear to the audience from nearly the beginning.

It is significant, however, that Freda does not suspect her husband of killing his first wife or of plotting to kill her. This is unusual when compared to most gothic film narratives. For example, in both versions of Gaslight (1940, UK, Thorold Dickinson and 1944, US, George Cukor) as well as Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) the heroine increasingly comes to suspect her husband. Cast a Dark Shadow diverges from Rebecca and Suspicion since Teddy’s murderous intentions are clear to the audience from nearly the beginning.

It is also worth considering the age-gap couples of the older Maxim and the young second Mrs de Winter in Rebecca and Teddy and Molly in Cast a Dark Shadow. Teddy is by many years Molly’s junior, and at first we thought that perhaps he was her doting son or nephew. As often happens with older husbands in gothic films, Molly takes on a teaching role in regard to the younger Teddy. Teddy’s speech and lack of social graces are corrected by his wife. ‘‘Ome’ should be ‘home’, Teddy should not speak with his mouth full or lounge on the sofa with his feet up, and he ought to get up when a visitor departs. Furthermore, in contrast to other gothic narratives, it is Molly’s resistance rather than her acquiescence that causes her to be killed. Teddy is unaware that Molly made a will after their marriage. He therefore mistakenly believes that the new will she insists on drawing up cuts him out in favour of her sister, Dora.

It is also worth considering the age-gap couples of the older Maxim and the young second Mrs de Winter in Rebecca and Teddy and Molly in Cast a Dark Shadow. Teddy is by many years Molly’s junior, and at first we thought that perhaps he was her doting son or nephew. As often happens with older husbands in gothic films, Molly takes on a teaching role in regard to the younger Teddy. Teddy’s speech and lack of social graces are corrected by his wife. ‘‘Ome’ should be ‘home’, Teddy should not speak with his mouth full or lounge on the sofa with his feet up, and he ought to get up when a visitor departs. Furthermore, in contrast to other gothic narratives, it is Molly’s resistance rather than her acquiescence that causes her to be killed. Teddy is unaware that Molly made a will after their marriage. He therefore mistakenly believes that the new will she insists on drawing up cuts him out in favour of her sister, Dora.

Teddy’s second wife, Freda, even more so than Molly, is not the unsuspecting innocent heroine of most gothic narratives. Not only has she worked (as a barmaid) but she has sexual experience: she has been married and widowed. Freda’s prompt quashing of Teddy’s suggestion of separate bedrooms (‘I didn’t marry you for companionship’) reinforces this. Teddy himself describes her as ‘vulgar’ in one of the several conversations he holds with his late wife. (His speaking to Molly’s empty chair, and her role as teacher/mother to Teddy reminded us of Psycho (1960, Alfred Hitchcock) – both Teddy and Norman Bates are unhinged killers.)

Teddy’s second wife, Freda, even more so than Molly, is not the unsuspecting innocent heroine of most gothic narratives. Not only has she worked (as a barmaid) but she has sexual experience: she has been married and widowed. Freda’s prompt quashing of Teddy’s suggestion of separate bedrooms (‘I didn’t marry you for companionship’) reinforces this. Teddy himself describes her as ‘vulgar’ in one of the several conversations he holds with his late wife. (His speaking to Molly’s empty chair, and her role as teacher/mother to Teddy reminded us of Psycho (1960, Alfred Hitchcock) – both Teddy and Norman Bates are unhinged killers.)

Freda has a firm grip on the reason for men’s interest in her: in the past they have cared more about her ‘moneybags’ than the ‘old bag’. She also wishes to keep a firm grip on her finances as she insists that she and Teddy are equal in terms of partnership – they must match each other ‘pound for pound’. Freda fails to check Molly’s will deposited at Somerset House, however, and is subsequently pestered by Teddy to invest in a business deal. This scene takes place next to a quarry with a prominent ‘danger’ sign. Teddy has ostensibly encouraged Freda to climb over the safety fence in order to pick flowers. In addition to the location, Freda seems further to be in peril as he raises his hand to her when she refuses to go along with his plan. She threatens that ‘I’ll hit you back’, and the authority with which Lockwood invests the line makes Teddy, and the audience, believe her.

Freda has a firm grip on the reason for men’s interest in her: in the past they have cared more about her ‘moneybags’ than the ‘old bag’. She also wishes to keep a firm grip on her finances as she insists that she and Teddy are equal in terms of partnership – they must match each other ‘pound for pound’. Freda fails to check Molly’s will deposited at Somerset House, however, and is subsequently pestered by Teddy to invest in a business deal. This scene takes place next to a quarry with a prominent ‘danger’ sign. Teddy has ostensibly encouraged Freda to climb over the safety fence in order to pick flowers. In addition to the location, Freda seems further to be in peril as he raises his hand to her when she refuses to go along with his plan. She threatens that ‘I’ll hit you back’, and the authority with which Lockwood invests the line makes Teddy, and the audience, believe her.

Freda is therefore aware of Teddy’s faults. As well as witnessing his threatening behaviour, she was unsurprised much earlier on when she learned that he had tricked Emmie working for him for free by ‘paying’ her with the £200 legacy Molly left her. Later, when complaining about ‘Charlotte’ and Teddy’s closeness, Freda says she would support Teddy in fleecing her. In some ways they are kindred spirits: she also married above her class, to a publican, and gives the impression of having cared little for her husband. (While Teddy does profess to have cared for Molly, he still killed her.) Nonetheless, Freda disbelieves ‘Charlotte’s’ accusation against Teddy, insisting that: ‘he’s a bad boy but he’s not that bad’. Freda’s blinkered attitude is perhaps explained by her earlier response to Teddy’s admission that he has no money: rather than railing against him she tells him ‘So help me I love you’. This is reinforced by Freda’s acknowledgment at the film’s close that this was ‘the one time I let my heart rule my head’.

Emmie and ‘Charlotte’ are also women in peril. Of all the women in the film, Emmie is the most vulnerable to Teddy’s manipulation. Teddy is well aware of the type of woman he can target. When Teddy tells ‘Charlotte’ that he knew she was not keen on him, he explains that ‘I know who I appeal to and who I don’t’. He says that Freda was susceptible as they belong to the same class, and Molly because of her advanced age. Emmie qualifies on both counts. She is shown to occupy a lower class than even the ‘vulgar’ Freda. When they are introduced, Emmie seems unsure of how to address Freda, advising her to ‘come this way, lady’. Furthermore, as an employee, she is dependent on the Bares for the roof over her head. When Teddy learns he has not been left money in Molly’s will he tells Emmie she will have to find another home. Her reply ‘but this is my home’ touchingly underlines her helpless situation.

Emmie and ‘Charlotte’ are also women in peril. Of all the women in the film, Emmie is the most vulnerable to Teddy’s manipulation. Teddy is well aware of the type of woman he can target. When Teddy tells ‘Charlotte’ that he knew she was not keen on him, he explains that ‘I know who I appeal to and who I don’t’. He says that Freda was susceptible as they belong to the same class, and Molly because of her advanced age. Emmie qualifies on both counts. She is shown to occupy a lower class than even the ‘vulgar’ Freda. When they are introduced, Emmie seems unsure of how to address Freda, advising her to ‘come this way, lady’. Furthermore, as an employee, she is dependent on the Bares for the roof over her head. When Teddy learns he has not been left money in Molly’s will he tells Emmie she will have to find another home. Her reply ‘but this is my home’ touchingly underlines her helpless situation.

Teddy proceeds to further outline Emmie’s difficulties: she is too old to find another job. Despite her advanced age, Emmie has a childlike innocence. Both Molly and Teddy when asking her to leave the room, or to get on with a job she has been given, tell her to ‘toddle’. She is not only easily manipulated by Teddy in terms of her legacy, but is persuaded by him to tell Freda of his and Molly’s previous happiness – to give the recent widow hope. Both Freda and Molly’s lawyer Phillip Mortimer (Robert Flemyng) comment on the fact that Emmie seems ‘simple’. Emmie’s trusting nature means that she is a risk to Teddy since while she is loyal to him, she may give away information without realising it. She has already guilelessly praised Teddy in Phillip’s presence for helping her to practice the evidence she later gave at Molly’s inquest. Indeed, Phillip says that he hopes he will get the truth about Teddy’s guilt through Emmie since she has lived in the Bares’ house throughout. In turn this places Emmie at risk from Teddy.

Teddy proceeds to further outline Emmie’s difficulties: she is too old to find another job. Despite her advanced age, Emmie has a childlike innocence. Both Molly and Teddy when asking her to leave the room, or to get on with a job she has been given, tell her to ‘toddle’. She is not only easily manipulated by Teddy in terms of her legacy, but is persuaded by him to tell Freda of his and Molly’s previous happiness – to give the recent widow hope. Both Freda and Molly’s lawyer Phillip Mortimer (Robert Flemyng) comment on the fact that Emmie seems ‘simple’. Emmie’s trusting nature means that she is a risk to Teddy since while she is loyal to him, she may give away information without realising it. She has already guilelessly praised Teddy in Phillip’s presence for helping her to practice the evidence she later gave at Molly’s inquest. Indeed, Phillip says that he hopes he will get the truth about Teddy’s guilt through Emmie since she has lived in the Bares’ house throughout. In turn this places Emmie at risk from Teddy.

In fact, it is another woman who causes for the truth to be revealed. Towards the end of the film ‘Charlotte’ unwittingly places herself in danger when she visits what she thinks is the Bares’ empty house in her quest for evidence. She enters the shadowy hall as the clock strikes. This invokes a sense that ‘Charlotte’ has come to mete out justice and it is a time of reckoning for Teddy. She is certainly a determined woman. When Teddy reveals that he knows ‘Charlotte’s’ true identity (partly because she was

In fact, it is another woman who causes for the truth to be revealed. Towards the end of the film ‘Charlotte’ unwittingly places herself in danger when she visits what she thinks is the Bares’ empty house in her quest for evidence. She enters the shadowy hall as the clock strikes. This invokes a sense that ‘Charlotte’ has come to mete out justice and it is a time of reckoning for Teddy. She is certainly a determined woman. When Teddy reveals that he knows ‘Charlotte’s’ true identity (partly because she was  familiar with the house’s layout and idiosyncrasies), and admits to murdering her sister, her concern is for Freda. She stands up to Teddy, refusing to leave, and only departing when Freda returns and asks her to go. ‘Charlotte’ even risks her life again, coming back to the house to make sure others know of his guilt. From here, ‘Charlotte’ witnesses Teddy’s escape and hears him crash her car: his tampering with her brakes has backfired.

familiar with the house’s layout and idiosyncrasies), and admits to murdering her sister, her concern is for Freda. She stands up to Teddy, refusing to leave, and only departing when Freda returns and asks her to go. ‘Charlotte’ even risks her life again, coming back to the house to make sure others know of his guilt. From here, ‘Charlotte’ witnesses Teddy’s escape and hears him crash her car: his tampering with her brakes has backfired.

We also briefly considered the film in relation to Margaret Lockwood’s screen image. Her appearances in Gainsborough melodramas in the 1940s (such as the aristocratic and adventurous Barbara in Leslie Arliss’ 1945 film The Wicked Lady) helped to ensure her status as a top box office draw during the decade. (You can see a summary of our discussion on The Wicked Lady here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2014/02/03/summary-of-discussion-on-the-wicked-lady/) Lockwood’s 1950s films were less successful, as Cast a Dark Shadow director Lewis Gilbert commented in later years (Brian McFarlane, Gilbert Interview, An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 221). Lockwood is still afforded a star entrance in Cast a Dark Shadow, however. She enters the film about a third of the way in, sweeping down the stairs at the tearoom in which Teddy is lying in wait. Post-production publicity downplayed Lockwood’s involvement though. Bogarde later noted that he was initially placed under Lockwood in the film’s billing, until it was realised that ‘her name had killed it’ (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70). Gilbert echoes these sentiments, noting that the attachment of Lockwood’s name was ‘counter-productive’ (McFarlane, Gilbert Interview, p. 221). Both Bogarde and Gilbert opined it a shame that Lockwood’s ‘great’ performance was not appreciated by audiences (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70, Gilbert Interview, p. 221). Lockwood did not appear in another feature film for over twenty years, though she stated in a 1973 interview that she was ‘glad’ to have played the role. (McFarlane, p. 374, quoting from Eric Braun ‘The Indestructibles’, Films and Filming, September 1973, p. 38.) This is supported by the fact that the next year Lockwood repeated her role in a now-believed lost TV version, co-starring Derek Farr the originator of the role of Teddy on stage.

We also briefly considered the film in relation to Margaret Lockwood’s screen image. Her appearances in Gainsborough melodramas in the 1940s (such as the aristocratic and adventurous Barbara in Leslie Arliss’ 1945 film The Wicked Lady) helped to ensure her status as a top box office draw during the decade. (You can see a summary of our discussion on The Wicked Lady here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2014/02/03/summary-of-discussion-on-the-wicked-lady/) Lockwood’s 1950s films were less successful, as Cast a Dark Shadow director Lewis Gilbert commented in later years (Brian McFarlane, Gilbert Interview, An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 221). Lockwood is still afforded a star entrance in Cast a Dark Shadow, however. She enters the film about a third of the way in, sweeping down the stairs at the tearoom in which Teddy is lying in wait. Post-production publicity downplayed Lockwood’s involvement though. Bogarde later noted that he was initially placed under Lockwood in the film’s billing, until it was realised that ‘her name had killed it’ (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70). Gilbert echoes these sentiments, noting that the attachment of Lockwood’s name was ‘counter-productive’ (McFarlane, Gilbert Interview, p. 221). Both Bogarde and Gilbert opined it a shame that Lockwood’s ‘great’ performance was not appreciated by audiences (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70, Gilbert Interview, p. 221). Lockwood did not appear in another feature film for over twenty years, though she stated in a 1973 interview that she was ‘glad’ to have played the role. (McFarlane, p. 374, quoting from Eric Braun ‘The Indestructibles’, Films and Filming, September 1973, p. 38.) This is supported by the fact that the next year Lockwood repeated her role in a now-believed lost TV version, co-starring Derek Farr the originator of the role of Teddy on stage.

Due to our Bogarde-focus we also discussed Bogarde’s role in the film – both on and off. As noted in previous blog posts on the films we have screened, Bogarde’s character in Cast a Dark Shadow is repulsive and also coded as of the working classes (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/11/21/summary-of-discussion-on-libel/_) Chronologically the film can be placed between previously screened films Hunted (1952, Charles Crichton) and Libel (1959, Anthony Asquith). Both of these films afforded Bogarde the opportunity to be simultaneously villainous and vulnerable. Cast a Dark Shadow in fact returns him to his smaller earlier role as a low-class criminal who kills George Dixon (of Dock Green fame) in The Blue Lamp (1950, Basil Dearden).

Due to our Bogarde-focus we also discussed Bogarde’s role in the film – both on and off. As noted in previous blog posts on the films we have screened, Bogarde’s character in Cast a Dark Shadow is repulsive and also coded as of the working classes (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/11/21/summary-of-discussion-on-libel/_) Chronologically the film can be placed between previously screened films Hunted (1952, Charles Crichton) and Libel (1959, Anthony Asquith). Both of these films afforded Bogarde the opportunity to be simultaneously villainous and vulnerable. Cast a Dark Shadow in fact returns him to his smaller earlier role as a low-class criminal who kills George Dixon (of Dock Green fame) in The Blue Lamp (1950, Basil Dearden).

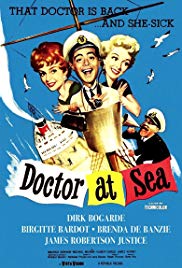

The film should also be placed in the context of Bogarde’s other films released in 1955. Simba (Brian Desmond Hurst) was an adventure story, and Doctor at Sea (Ralph Thomas) the second in a comedy series. The latter is an especially important part of Bogarde’s screen image which the melodrama research group has had little chance to explore. The significance of the series to Bogarde’s screen image at the time is implied by a letter from a member of the public published in the 24th September 1955 issue of UK fan magazine Picturegoer. Miss E Smyth asked ‘Can’t Dirk Bogarde have a really dramatic role to prove himself an actor as well as a much-admired star?’ (p. 30). While we cannot be sure this was from a real person, it comments on an awareness of Bogarde’s increasingly frequent appearances in comedies and ties kudos for acting to dramatic performances. Picturegoer’s response is also instructive: ‘But picturegoers used to complain that Bogarde had too many dramatic, hunted-by-police roles…’ Cast a Dark Shadow therefore supplies a useful contrast to both comedies (the Doctor series) and man-on-the run films like Hunted.

The film should also be placed in the context of Bogarde’s other films released in 1955. Simba (Brian Desmond Hurst) was an adventure story, and Doctor at Sea (Ralph Thomas) the second in a comedy series. The latter is an especially important part of Bogarde’s screen image which the melodrama research group has had little chance to explore. The significance of the series to Bogarde’s screen image at the time is implied by a letter from a member of the public published in the 24th September 1955 issue of UK fan magazine Picturegoer. Miss E Smyth asked ‘Can’t Dirk Bogarde have a really dramatic role to prove himself an actor as well as a much-admired star?’ (p. 30). While we cannot be sure this was from a real person, it comments on an awareness of Bogarde’s increasingly frequent appearances in comedies and ties kudos for acting to dramatic performances. Picturegoer’s response is also instructive: ‘But picturegoers used to complain that Bogarde had too many dramatic, hunted-by-police roles…’ Cast a Dark Shadow therefore supplies a useful contrast to both comedies (the Doctor series) and man-on-the run films like Hunted.

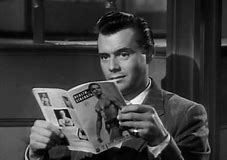

We also noted that Bogarde’s later screen image (his role in Basil Dearden’s Victim, 1961), as well as his star image (knowledge of his personal life) influenced a specific aspect our reading of his character in Cast a Dark Shadow. When Teddy is waiting for Freda at the seaside tearoom he is reading a men’s health magazine which has a semi-naked man on its cover. Perusing such a publication might be thought to indicate a preference for men. Given Teddy’s first marriage to a woman much older than himself, his somewhat camp eyebrow-raising, and revelations later in

We also noted that Bogarde’s later screen image (his role in Basil Dearden’s Victim, 1961), as well as his star image (knowledge of his personal life) influenced a specific aspect our reading of his character in Cast a Dark Shadow. When Teddy is waiting for Freda at the seaside tearoom he is reading a men’s health magazine which has a semi-naked man on its cover. Perusing such a publication might be thought to indicate a preference for men. Given Teddy’s first marriage to a woman much older than himself, his somewhat camp eyebrow-raising, and revelations later in  the film about some of his earlier behaviour, we contemplated his sexuality. This is not clear-cut. Teddy’s pursuit of Freda is for business rather than pleasure, though he seems gratified when she refuses separate bedrooms and points out that she has not married him for companionship. His narcissism leaves little room for anyone other than himself.

the film about some of his earlier behaviour, we contemplated his sexuality. This is not clear-cut. Teddy’s pursuit of Freda is for business rather than pleasure, though he seems gratified when she refuses separate bedrooms and points out that she has not married him for companionship. His narcissism leaves little room for anyone other than himself.

As well as considering where Cast a Dark Shadow fits with Bogarde’s screen and star images we pondered how much he contributed to the role. Bogarde was apparently approached by Janet Green to appear in her original play (McFarlane, Gilbert Interview, p. 221). This suggests that the character was written with Bogarde in mind for both stage and screen. He has stated that the ‘unwholesomeness’ of the character was appealed to him and made it fun (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70) even though we might think it allowed for less nuance. Lockwood was persuaded to undertake her role by Bogarde (McFarlane, Bogarde Interview, p. 70; McFarlane, p. 374, quoting Lockwood in Braun, ‘The Indestructibles’, p. 38). This therefore reveals Bogarde’s wider influence in the production of the film, cautioning us not to assume passivity on the part of a star and to acknowledge the many people are involved in realising a director’s vision.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk and let me know you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.