(Apologies for the few months delay in posting this summary. I’ve backdated it so that it fits in with the flow of discussion on the blog, allowing the focus to be on our more recent events such as The War Illustrated project.)

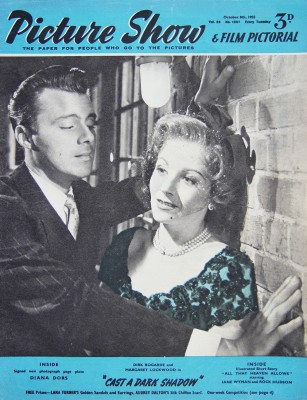

Our discussion on the film covered: its relation to melodrama; its music; its setting in time and place; films it reminded us of; the film’s place in Dirk Bogarde’s screen and star images; material in magazines.

We discussed melodrama in terms of the suffering of the film’s main character, composer Gustav von Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde). The film unfolds at a leisurely pace with the seriousness of Von Aschenbach’s purpose for staying at a hotel in Venice, an illness, revealed as time progresses. This is compounded by Von Aschenbach contracting cholera after witnessing those around him undergoing the awful effects of the disease. The film ends with dying on a beach. Furthermore, Von Aschenbach undergoes emotional distress as he feels unrequited, and inappropriate, desire for an adolescent boy, the Polish Tadzio (Bjorn Andresen).

We discussed melodrama in terms of the suffering of the film’s main character, composer Gustav von Aschenbach (Dirk Bogarde). The film unfolds at a leisurely pace with the seriousness of Von Aschenbach’s purpose for staying at a hotel in Venice, an illness, revealed as time progresses. This is compounded by Von Aschenbach contracting cholera after witnessing those around him undergoing the awful effects of the disease. The film ends with dying on a beach. Furthermore, Von Aschenbach undergoes emotional distress as he feels unrequited, and inappropriate, desire for an adolescent boy, the Polish Tadzio (Bjorn Andresen).

The film’s flashbacks also convey Von Aschenbach’s previous suffering. This is mostly emotional, rather than physical. Von Aschenbach has an extreme reaction to the poor reception of one of his musical works, and subsequently collapses. The inclusion of these scenes suggests that Von Aschenbach is still feeling their effects. Not all the flashbacks are unhappy. Some show Von Aschenbach happily spending time with his wife and daughter. This fits in with the rhythm of melodrama, since it shows both the highs (happy moments with his wife and child) and the lows (his extreme grief at their loss). We thought it interesting that Von Aschenbach’s wife and child, and indeed the happiness, was included given the film’s main focus on Von Aschenbach’s controversial desire for young Tadzio. Von Aschenbach is a complex character with a backstory which is revealed in a piecemeal fashion.

The film’s flashbacks also convey Von Aschenbach’s previous suffering. This is mostly emotional, rather than physical. Von Aschenbach has an extreme reaction to the poor reception of one of his musical works, and subsequently collapses. The inclusion of these scenes suggests that Von Aschenbach is still feeling their effects. Not all the flashbacks are unhappy. Some show Von Aschenbach happily spending time with his wife and daughter. This fits in with the rhythm of melodrama, since it shows both the highs (happy moments with his wife and child) and the lows (his extreme grief at their loss). We thought it interesting that Von Aschenbach’s wife and child, and indeed the happiness, was included given the film’s main focus on Von Aschenbach’s controversial desire for young Tadzio. Von Aschenbach is a complex character with a backstory which is revealed in a piecemeal fashion.

We also commented on Death in Venice’s relation to the mystery, violence and chase elements of melodrama. Only the last of these was present in the film. As Von Aschenbach becomes increasingly ill, he worries about Tadzio’s health, and pursues him through Venice’s streets. This ends with him collapsing in the street with exhaustion. Unusually for a pursuer in the chase, then, Von Aschenbach action causes him suffering, heightening this aspect of melodrama.

Death in Venice’s musical score, later released by EMI, was also discussed by the group in terms of melodrama. The opening shots of the film are languid long takes accompanied by the music of Gustav Mahler. Music also punctuates other significant moments in the film. Von Aschenbach feels embarrassed by his desire for Tadzio and decides to leave Venice. As he embarks on a long boat journey leisurely music accompanies the close-up shots of his sad face. After a mix up with Von Aschenbach’s luggage, he chooses to return to his hotel, and to Tadzio. Again, close-ups of Von Aschenbach are provided, though he is now smiling, and the mood of the music also seems to have lifted. Other points at which music is used especially effectively include the chase sequence referenced above, as well as the moving end of the film where Von Aschenbach falls ill on a beach and passes away.

Death in Venice’s musical score, later released by EMI, was also discussed by the group in terms of melodrama. The opening shots of the film are languid long takes accompanied by the music of Gustav Mahler. Music also punctuates other significant moments in the film. Von Aschenbach feels embarrassed by his desire for Tadzio and decides to leave Venice. As he embarks on a long boat journey leisurely music accompanies the close-up shots of his sad face. After a mix up with Von Aschenbach’s luggage, he chooses to return to his hotel, and to Tadzio. Again, close-ups of Von Aschenbach are provided, though he is now smiling, and the mood of the music also seems to have lifted. Other points at which music is used especially effectively include the chase sequence referenced above, as well as the moving end of the film where Von Aschenbach falls ill on a beach and passes away.

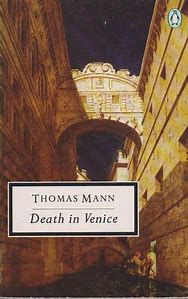

The film’s extra-diegetic music seems especially appropriate because the occupation of Von Aschenbach is altered from a writer in Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella, to a composer. Such a change also suits the medium of sound film. Von Achenbach’s musical background affords opportunities for music to be present within the diegesis. The flashback to the failure of Von Aschenbach’s concert includes music. We also see Von Achenbach’s responses to others playing music. Tadzio briefly picks out a few notes, badly, on the piano at the hotel. This does not seem to dampen Von Aschenbach’s desire. But he appears to be more judgmental about local musicians who are playing several instruments to try and inject some jollity into the cholera-stricken district.

The film’s extra-diegetic music seems especially appropriate because the occupation of Von Aschenbach is altered from a writer in Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella, to a composer. Such a change also suits the medium of sound film. Von Achenbach’s musical background affords opportunities for music to be present within the diegesis. The flashback to the failure of Von Aschenbach’s concert includes music. We also see Von Achenbach’s responses to others playing music. Tadzio briefly picks out a few notes, badly, on the piano at the hotel. This does not seem to dampen Von Aschenbach’s desire. But he appears to be more judgmental about local musicians who are playing several instruments to try and inject some jollity into the cholera-stricken district.

The film’s European Edwardian-era setting as a backdrop for Von Aschenbach’s suffering was also commented on. This is undoubtedly connected to the date and location of the original setting of Mann’s, novella. But we thought that Death in Venice’s title, as well as its depiction of disease, foreshadowed the upcoming first world war which would decimate Europe. Tadzio’s family also reminded us of the Russian royals the Romanovs who were killed following the Russian Revolution which began in 1917. Much of this was connected to the film’s mise en scene. The hotel is large and ornately furnished, denoting its expensive nature. The people who can afford to stay there are generally of the upper classes – such as Tadzio’s family. The clothing worn by Tadzio’s family, especially the exquisite dresses, also suggest wealth. Tadzio’s sailor suit costume reminded us of some of the photographs of the Romanovs. His costume therefore effectively reflects the time period in which the film is set, and his status as a member of the upper class. It also significantly emphasises his youth in comparison to Von Aschenbach. (We thought that Tadzio’s hair style reproduced the 1970s of the film’s era of production, however!) We also briefly mentioned other films set in Italy’s iconic landscape, such as Don’t Look (1973, Nicolas Roeg) and A Room with a View (1985, Merchant and Ivory).

Since we have been screening several Bogarde films, we compared the melodrama in Death in Venice to other Bogarde films we’ve discussed. The suffering of Von Aschenbach raised thoughts about Esther Waters (1948, Ian Dalrymple), especially William Latch’s death-bed scene. We thought that the beautifully lit last moments of Bogarde’s character recalled similar deaths of heroines in film melodramas (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/10/06/summary-of-discussion-on-esther-waters/) The fact that some aspects of chase were involved in Death in Venice reminded us of our discussion of Hunted (1952, Charles Crichton), which depicts killer Chris Lloyd’s attempt to escape pursuing police (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/10/18/summary-of-discussion-on-hunted/).

Since we have been screening several Bogarde films, we compared the melodrama in Death in Venice to other Bogarde films we’ve discussed. The suffering of Von Aschenbach raised thoughts about Esther Waters (1948, Ian Dalrymple), especially William Latch’s death-bed scene. We thought that the beautifully lit last moments of Bogarde’s character recalled similar deaths of heroines in film melodramas (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/10/06/summary-of-discussion-on-esther-waters/) The fact that some aspects of chase were involved in Death in Venice reminded us of our discussion of Hunted (1952, Charles Crichton), which depicts killer Chris Lloyd’s attempt to escape pursuing police (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2018/10/18/summary-of-discussion-on-hunted/).

Like Hunted, Victim (1961, Basil Dearden) combined suffering with mystery, violence, and chase. Death in Venice has significant differences from the UK-set Victim which had a crusading agenda tied to its time. Von Aschenbach’s desire for a young boy is of course not the same as the gay theme of Victim, and he is a more tragic character than Melville Farr in Victim. In Victim, Farr lost a close friend and was a closeted homosexual who the film suggested would continue to live with his wife in what might be seen as a compromise at a time when gay sex was illegal. Von Aschenbach’s sexual desire for a child places him further on the outskirts of society. His wish to be desirable to Tadzio means that Von Aschenbach undergoes a makeover. At the start of the film, Von Aschenbach visibly recoils from an older man whose hair looks suspiciously colourful and who is acting in a jaunty manner. After he becomes increasingly ill with cholera, Von Aschenbach visits a barber. The barber not only dyes

Like Hunted, Victim (1961, Basil Dearden) combined suffering with mystery, violence, and chase. Death in Venice has significant differences from the UK-set Victim which had a crusading agenda tied to its time. Von Aschenbach’s desire for a young boy is of course not the same as the gay theme of Victim, and he is a more tragic character than Melville Farr in Victim. In Victim, Farr lost a close friend and was a closeted homosexual who the film suggested would continue to live with his wife in what might be seen as a compromise at a time when gay sex was illegal. Von Aschenbach’s sexual desire for a child places him further on the outskirts of society. His wish to be desirable to Tadzio means that Von Aschenbach undergoes a makeover. At the start of the film, Von Aschenbach visibly recoils from an older man whose hair looks suspiciously colourful and who is acting in a jaunty manner. After he becomes increasingly ill with cholera, Von Aschenbach visits a barber. The barber not only dyes  Von Aschenbach’s hair to remove the grey but applies heavy make-up to his face. This sad visual demonstration that Von Achenbach is trying to recapture his youth is made even more poignant when he collapses sobbing in the street after losing sight of Tadzio. With his hair dye and make-up running, Von Aschenbach is a pitiful figure.

Von Aschenbach’s hair to remove the grey but applies heavy make-up to his face. This sad visual demonstration that Von Achenbach is trying to recapture his youth is made even more poignant when he collapses sobbing in the street after losing sight of Tadzio. With his hair dye and make-up running, Von Aschenbach is a pitiful figure.

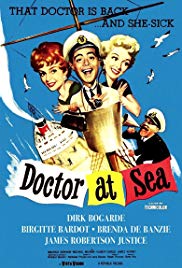

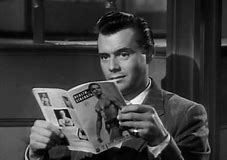

Bogarde did not exclusively portray provocative characters like Von Aschenbach after Victim. For example, in 1963 prior to playing the sinister titular character in Joseph Losey’s The Servant, Bogarde starred in I Could Go on Singing (Ronald Neame – see blog post here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2019/01/15/summary-of-discussion-on-i-could-go-on-singing/ ) as well as the last Doctor film, Doctor in Distress (Ralph Thomas). The move to comedy was even briefly seen in Bogarde’s work with Losey, as he appeared in the spy parody Modesty Blaise (1966) before the pair returned to more serious fare with Accident (1967). Bogarde’s work with other European directors included Visconti. Just before Death in Venice, Bogarde starred as a man with links to the Nazi party in Visconti’s The Damned (1969).

Bogarde did not exclusively portray provocative characters like Von Aschenbach after Victim. For example, in 1963 prior to playing the sinister titular character in Joseph Losey’s The Servant, Bogarde starred in I Could Go on Singing (Ronald Neame – see blog post here: https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2019/01/15/summary-of-discussion-on-i-could-go-on-singing/ ) as well as the last Doctor film, Doctor in Distress (Ralph Thomas). The move to comedy was even briefly seen in Bogarde’s work with Losey, as he appeared in the spy parody Modesty Blaise (1966) before the pair returned to more serious fare with Accident (1967). Bogarde’s work with other European directors included Visconti. Just before Death in Venice, Bogarde starred as a man with links to the Nazi party in Visconti’s The Damned (1969).

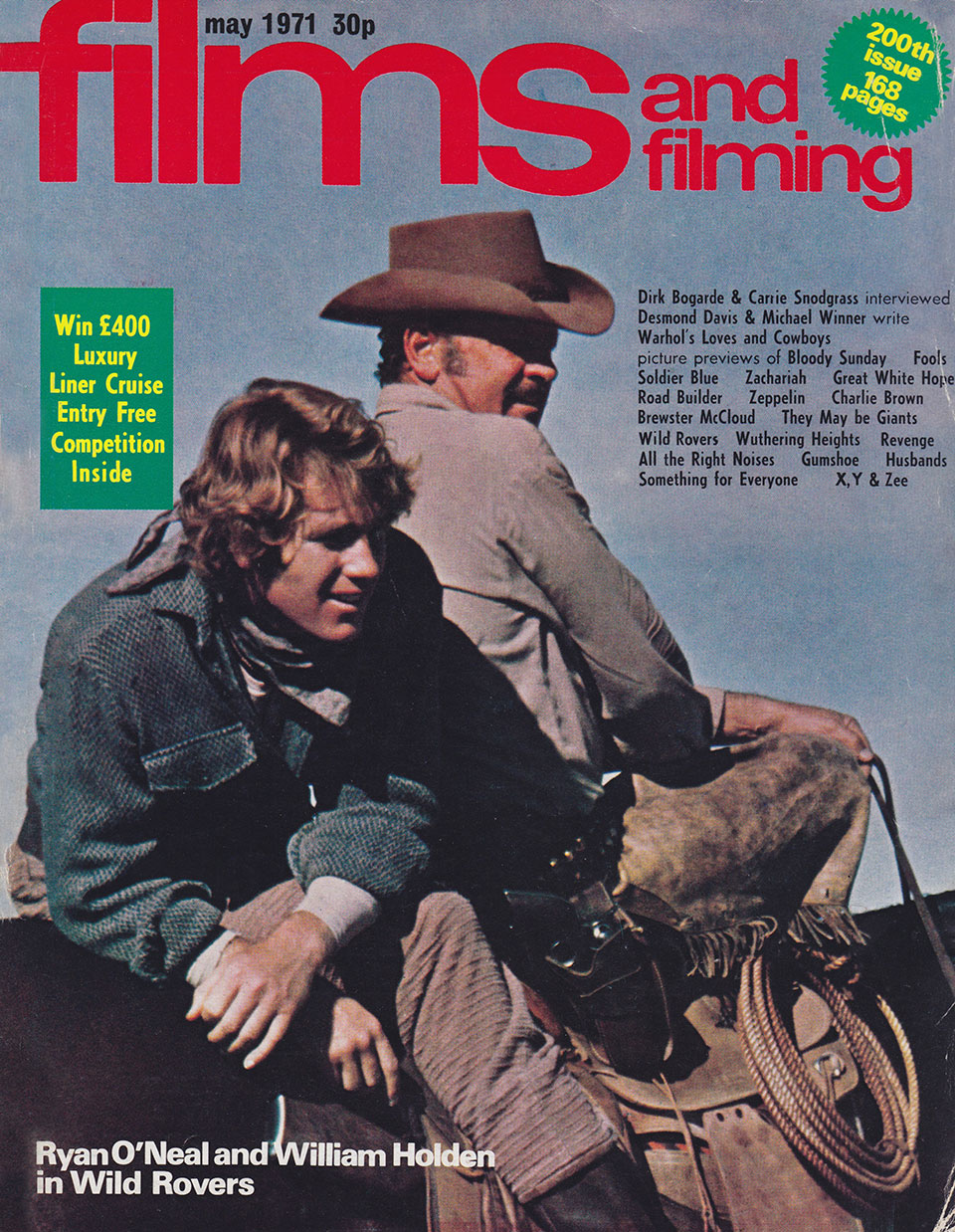

Bogarde’s more controversial roles – especially in The Damned and Death in Venice – seem to occur in films which in some way foreground artifice. The makeover scene in Death in Venice emphasises that while Von Aschenbach is trying to present himself in a certain way to Tadzio, as an actor, Bogarde, is also casting himself in a certain light. The hair dye and make-up in fact cover the greying hair and subtler make-up Bogarde is already sporting as Von Aschenbach. We also considered the Bogarde’s star image – the way his ‘real self’ appears to us. We primarily thought about this in relation to the changing of the novella’s character from a novelist (and perhaps a stand in for Thomas Mann) to another type of artist – a composer. Classical music could still have been heavily used in film whose main character was a novelist, so the change perhaps has further significance. Bogarde’s main writing career occurred well after Death in Venice’s 1971 release. His first memoir, Snakes and Ladders, appeared in 1978, with his first novel, A Gentle Occupation, following two years later. Bogarde had, however, previously written articles for magazines (perhaps most notably a series of 5 for Woman magazine in 1961). The fact that he writes essay and poems is even mentioned in coverage about Death in Venice from the time. In Gordon Gow’s interview with Bogarde in Films and Filming, he self-deprecatingly comments that he doubts anyone will want to publish him (May 1971, p. 49): https://dirkbogarde.co.uk/magazine/films-and-filming-may-1971/ Although it was unlikely to have happened, it would have been unfortunate if audiences mistakenly conflated the character of Von Aschenbach with the ‘real’ Bogarde.

Bogarde’s more controversial roles – especially in The Damned and Death in Venice – seem to occur in films which in some way foreground artifice. The makeover scene in Death in Venice emphasises that while Von Aschenbach is trying to present himself in a certain way to Tadzio, as an actor, Bogarde, is also casting himself in a certain light. The hair dye and make-up in fact cover the greying hair and subtler make-up Bogarde is already sporting as Von Aschenbach. We also considered the Bogarde’s star image – the way his ‘real self’ appears to us. We primarily thought about this in relation to the changing of the novella’s character from a novelist (and perhaps a stand in for Thomas Mann) to another type of artist – a composer. Classical music could still have been heavily used in film whose main character was a novelist, so the change perhaps has further significance. Bogarde’s main writing career occurred well after Death in Venice’s 1971 release. His first memoir, Snakes and Ladders, appeared in 1978, with his first novel, A Gentle Occupation, following two years later. Bogarde had, however, previously written articles for magazines (perhaps most notably a series of 5 for Woman magazine in 1961). The fact that he writes essay and poems is even mentioned in coverage about Death in Venice from the time. In Gordon Gow’s interview with Bogarde in Films and Filming, he self-deprecatingly comments that he doubts anyone will want to publish him (May 1971, p. 49): https://dirkbogarde.co.uk/magazine/films-and-filming-may-1971/ Although it was unlikely to have happened, it would have been unfortunate if audiences mistakenly conflated the character of Von Aschenbach with the ‘real’ Bogarde.

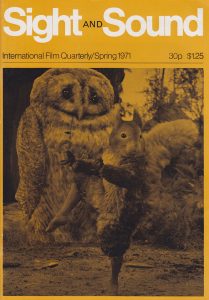

Such a view is of course retrospective, and heavily Bogarde-centric. Other magazine coverage from the time instead emphasised the similarity of Von Aschenbach to composer Gustav Mahler. Gordon Gow’s review of Death in Venice comments that Von Aschenbach’s hairstyling and spectacles make him resemble Mahler (Films and Filming, May 1971, p. 87). Furthermore, Gow claims that the director Visconti thought Mann’s novella was responding to Mahler’s 1911 death. By changing Von Aschenbach to a composer, Visconti believed he was able to draw out Mann’s original intent. A similar opinion is expressed in Philip Strick’s review in the Spring issue of Sight and Sound (pp. 103-4): https://dirkbogarde.co.uk/magazine/sight-and-sound-spring-1971/. Analysis of contemporary publicity and promotion therefore reveals that rather than distancing Von Aschenbach from Bogarde, changing him to a composer made him closer to Mahler.

Such a view is of course retrospective, and heavily Bogarde-centric. Other magazine coverage from the time instead emphasised the similarity of Von Aschenbach to composer Gustav Mahler. Gordon Gow’s review of Death in Venice comments that Von Aschenbach’s hairstyling and spectacles make him resemble Mahler (Films and Filming, May 1971, p. 87). Furthermore, Gow claims that the director Visconti thought Mann’s novella was responding to Mahler’s 1911 death. By changing Von Aschenbach to a composer, Visconti believed he was able to draw out Mann’s original intent. A similar opinion is expressed in Philip Strick’s review in the Spring issue of Sight and Sound (pp. 103-4): https://dirkbogarde.co.uk/magazine/sight-and-sound-spring-1971/. Analysis of contemporary publicity and promotion therefore reveals that rather than distancing Von Aschenbach from Bogarde, changing him to a composer made him closer to Mahler.

If you’re interested in reading more about Dirk Bogarde’s screen and star images, I’ve written several posts about the British Film Institute’s (BFI’s) collection of magazines bequeathed to them by his estate. You can find these on the NoRMMA blog: http://www.normmanetwork.com/tag/dirk-bogarde/

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp761@kent.ac.uk and let me know that you’d like me to add your thoughts to the melodrama blog.