Posted by Sarah

All are welcome to attend the fifth of the Summer Term’s discussion sessions, and our very first read-through, which will take place on the 5th of June, Jarman 7, from 5-7pm.

Jane is very kindly organising us for a read through of a melodrama play, and has provided the following information:

With a slightly different focus to our usual film-fare, this week we will be looking at an unpublished script for an early twentieth century stage melodrama, A Girl’s Cross Roads by Walter and Frederick Melville. The University’s Special Collections holds materials from the Melville family which reflect their influential standing in Victorian and Edwardian theatre.

The brothers Walter and Frederick Melville were part of the third generation of the Melville theatrical dynasty and, along with their four sisters and two brothers, were stalwarts of the stage as actors, directors, writers and owners and managers of theatres. Walter and Fred were particularly successful in London, where they owned and ran the Lyceum theatre from 1909 until 1939. They also had the Prince’s Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, built in 1911; this was later renamed the Shaftesbury Theatre.

The Melville brothers were hugely successful businessmen, eminently capable of producing hit dramas which pulled in the crowds. Their stock in trade was the winter pantomime, the details of which were famously kept a secret until the latest possible moment, and, of course, the Melville melodrama.

Although the Melvilles staged and adapted a number of popular melodramas in their time – including Sweeney Todd, East Lynne and The Count of Monte Cristo – it was a specific type of play for which Walter and Fred became particularly famous. These were called the ‘Bad Women’ dramas, since they usually portrayed an immoral woman, often one of the villains, in contrast to a morally upright though perhaps downtrodden heroine. Considering that these plays were hugely successful from c.1838-1912, when campaigns for women’s emancipation were gaining momentum, it might be thought that these plays were a comment on the times. Some audience members evidently thought so, since Walter was obliged to write to a newspaper to explain that he was not ‘a woman hater’. In fact, the roles which his plays offered to actresses could be far better roles than they could take in less controversial dramas.

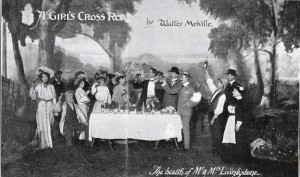

A Girl’s Cross Roads was first performed in 1903, probably at the Standard Theatre in Shoreditch. The plot tells the tale of Jack Livingstone, a well off gentleman, and his wife, Barbara Wade, a woman who is convinced that Jack made a mistake in marrying her. Jack’s friend Dr. Weston, who tells the sad tale of a woman who drank herself to death, is sure that he’s seen that look on Barbara’s face before; meanwhile the girl whom both Weston and Jack were in love with (and perhaps still are), Constance, has decided to leave the countryside to make a new life in London. The villains of the piece are quick to take advantage of Barbara’s fears, leading her down a path from which there is no return. Running alongside the main plot and intersecting with the other characters, a father looks for his daughter only to be appalled by what he finds, and the comic couple Toby and Tilly try to make their way in the world. Moving from the English countryside to the heart of London, the play takes in themes of the time including alcoholism, murder, intrigue and extortion in the thrilling ride of a typical Melville melodrama with tragedy, comedy and expertly handled suspense. This particular play is interesting, since it deals with fewer absolutes in terms of morally right or wrong, and calls into question the simplistic expectations from the audience of the popular stage.

A Girl’s Cross Roads was first performed in 1903, probably at the Standard Theatre in Shoreditch. The plot tells the tale of Jack Livingstone, a well off gentleman, and his wife, Barbara Wade, a woman who is convinced that Jack made a mistake in marrying her. Jack’s friend Dr. Weston, who tells the sad tale of a woman who drank herself to death, is sure that he’s seen that look on Barbara’s face before; meanwhile the girl whom both Weston and Jack were in love with (and perhaps still are), Constance, has decided to leave the countryside to make a new life in London. The villains of the piece are quick to take advantage of Barbara’s fears, leading her down a path from which there is no return. Running alongside the main plot and intersecting with the other characters, a father looks for his daughter only to be appalled by what he finds, and the comic couple Toby and Tilly try to make their way in the world. Moving from the English countryside to the heart of London, the play takes in themes of the time including alcoholism, murder, intrigue and extortion in the thrilling ride of a typical Melville melodrama with tragedy, comedy and expertly handled suspense. This particular play is interesting, since it deals with fewer absolutes in terms of morally right or wrong, and calls into question the simplistic expectations from the audience of the popular stage.

As far as we know, none of the Melville scripts, including the Bad Women dramas, have ever been published and there has been very little research into them. This read through on the 5th June will be the first time this play has been performed in any sense for a considerable time – perhaps since the last time it was performed on stage. This will be a great opportunity to return to the days of high melodrama and perhaps confront some of our perceptions of the stereotypical stage melodrama.

Do join us if you can, for a wonderful opportunity to actively engage with some melodrama history.