(Apologies for the couple of months delay in posting this. I’ve backdated it so that it fits with the ‘timeline’ of our Bogarde screenings and does not interrupt more recent news about The War Illustrated workshops etc.)

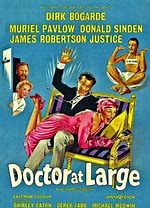

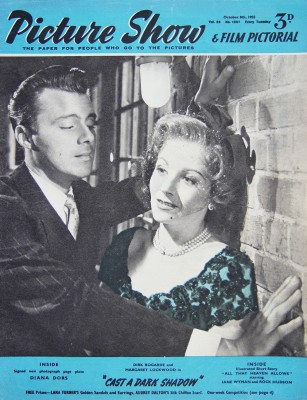

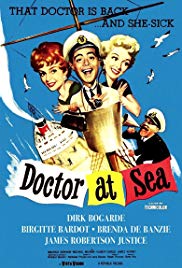

As noted in the introduction to the screening of Doctor in the House, the comedy can hardly be described as a melodrama. We showed it due to the important place it has in Dirk Bogarde’s screen image. The film was hugely popular in the UK in the year of its release (1954). It also had an afterlife as Bogarde continued to play the role of Simon Sparrow in later films in the series (all directed by Ralph Thomas and produced by Betty Box): Doctor at Sea (1955), Doctor at Large (1957), Doctor in Distress (1963) and a cameo as Simon Sparrow in Wendy Toye’s non-Doctor film We Joined the Navy (1962). This was significantly the only screen character Bogarde played more than once, though he did not appear in the films Doctor in Love (1960), Doctor in Clover (1966) or Doctor in Trouble (1970). It is likely that audiences from the time would have especially connected Bogarde to Simon Sparrow. In the text below, I therefore go into some detail on Simon Sparrow’s personality and Bogarde’s interpretation of the role. This is aided by some consideration of the film’s other characters. Our post-film discussion also touched on how we as modern audience members viewed the film today. For many of us, this was shaped by our knowledge of the film’s sequels and its similarity to the humour exhibited in the ‘Carry On’ series of films (1958-1992). This brought up the matter of sexism, as well as differences in generational and national perspectives. I briefly discuss some of these matters in relation to the film’s reception on its 1955 US release.

Doctor in the House was based on Doctor Richard Gordon’s 1952 novel of the same name. The series of 18 novels (the final, Doctor in the Soup, was published in 1986) drew on Gordon’s own experiences as a medical student and later a qualified doctor. This was emphasised in the novels by the use of Gordon’s own name for the main character. This character was re-christened Simon Sparrow in the film, with Bogarde later revealing that he chose the name (in Brian McFarlane’s An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 69). It is an especially appropriate moniker: the Hebrew meaning of the name Simon is ‘listen’, while Sparrow conveys the image of a sweet and non-threatening garden bird. Simon is a good-natured man, trying his best to deal with the attentions of women while completing his medical studies at St Swithin’s hospital.

Doctor in the House was based on Doctor Richard Gordon’s 1952 novel of the same name. The series of 18 novels (the final, Doctor in the Soup, was published in 1986) drew on Gordon’s own experiences as a medical student and later a qualified doctor. This was emphasised in the novels by the use of Gordon’s own name for the main character. This character was re-christened Simon Sparrow in the film, with Bogarde later revealing that he chose the name (in Brian McFarlane’s An Autobiography of British Cinema, 1997, p. 69). It is an especially appropriate moniker: the Hebrew meaning of the name Simon is ‘listen’, while Sparrow conveys the image of a sweet and non-threatening garden bird. Simon is a good-natured man, trying his best to deal with the attentions of women while completing his medical studies at St Swithin’s hospital.

Simon’s experiences with women take place at home and at work. He receives the attentions of his stern landlady Mrs Groaker’s (Joan Hickson) beautiful daughter Milly (Shirley Eaton) when she engineers an opportunity for him to examine her ankle. His unworldliness and embarrassment mean that he promptly leaves his lodgings to move in with some fellow male medical students. Simon’s housemates gently tease him about his lack of success with women, even asking ‘Don’t you want a girlfriend? Or have you a mother complex?’ In order to persuade his friends that he is keen to be in a couple, Simon agrees to be set up with ‘Rigor Mortis’ (Joan Sims). The film’s sexism is evident as the men only refer to this nurse by her unflattering nickname. The technical term refers to the first stages of decomposition post-death, but presumably it has been bestowed upon the nurse to imply that she is not the most scintillating company. ‘Rigor Mortis’ is also referred to as a ‘trial’ girlfriend – i.e. only worthy as a temporary distraction until Simon finds someone better. The scene in which Simon and ‘Rigor Mortis’ spend time alone together pokes fun at them both, though. Her appetites, and perhaps her wish not to get involved with Simon, are referenced by her continuously munching on an apple. Simon seems to be making more of an effort with their date. He is dressed in a smoking jacket and some of his gestures imply that he is playing a part – that of a prospective seducer.

Simon’s experiences with women take place at home and at work. He receives the attentions of his stern landlady Mrs Groaker’s (Joan Hickson) beautiful daughter Milly (Shirley Eaton) when she engineers an opportunity for him to examine her ankle. His unworldliness and embarrassment mean that he promptly leaves his lodgings to move in with some fellow male medical students. Simon’s housemates gently tease him about his lack of success with women, even asking ‘Don’t you want a girlfriend? Or have you a mother complex?’ In order to persuade his friends that he is keen to be in a couple, Simon agrees to be set up with ‘Rigor Mortis’ (Joan Sims). The film’s sexism is evident as the men only refer to this nurse by her unflattering nickname. The technical term refers to the first stages of decomposition post-death, but presumably it has been bestowed upon the nurse to imply that she is not the most scintillating company. ‘Rigor Mortis’ is also referred to as a ‘trial’ girlfriend – i.e. only worthy as a temporary distraction until Simon finds someone better. The scene in which Simon and ‘Rigor Mortis’ spend time alone together pokes fun at them both, though. Her appetites, and perhaps her wish not to get involved with Simon, are referenced by her continuously munching on an apple. Simon seems to be making more of an effort with their date. He is dressed in a smoking jacket and some of his gestures imply that he is playing a part – that of a prospective seducer.  Any spell is quickly broken as Simon realises that his date is not enthusiastic about him. His offer to make her a cocoa is readily accepted and the mood changes from a possible hot date to a staid night in. Simon Sparrow’s behaviour here suits his name. He listens to his date’s aural and visual cues that she is not interested in him and rather than being angry or upset he is gentle and considerate.

Any spell is quickly broken as Simon realises that his date is not enthusiastic about him. His offer to make her a cocoa is readily accepted and the mood changes from a possible hot date to a staid night in. Simon Sparrow’s behaviour here suits his name. He listens to his date’s aural and visual cues that she is not interested in him and rather than being angry or upset he is gentle and considerate.

Simon’s interaction with another woman is also telling. He first meets model Isobel (Kay Kendall) just outside the hospital. She responds positively to his moderate attentions and their subsequent date can be usefully compared to his with ‘Rigor Mortis’. The two women are very different characters with Isobel’s job (and the fact she is played by Kendall) partly explaining her glamour and poise. Their date at an expensive club reveals the gulf between Isobel and Simon’s incomes and expectations. After seeing some of the prices on the menu, Simon arranges to be interrupted by an urgent phone-call. Unfortunately this backfires as he is then unable to stay when some friends of Isobel’s arrive and offer to pay for their meal. While Simon would have enjoyed a free meal, he seems intimated by Isobel’s forthright nature.

Simon’s interaction with another woman is also telling. He first meets model Isobel (Kay Kendall) just outside the hospital. She responds positively to his moderate attentions and their subsequent date can be usefully compared to his with ‘Rigor Mortis’. The two women are very different characters with Isobel’s job (and the fact she is played by Kendall) partly explaining her glamour and poise. Their date at an expensive club reveals the gulf between Isobel and Simon’s incomes and expectations. After seeing some of the prices on the menu, Simon arranges to be interrupted by an urgent phone-call. Unfortunately this backfires as he is then unable to stay when some friends of Isobel’s arrive and offer to pay for their meal. While Simon would have enjoyed a free meal, he seems intimated by Isobel’s forthright nature.

The woman who plays the largest part in the film is nurse Joy Gibson (Muriel Pavlow). Simon and Joy’s relationship gets off to a rocky start when they meet on his first day at the hospital amidst his suitcase embarrassingly spilling open. There are also misunderstandings as when they take a walk in the park each thinks the other is there under duress. This is overcome relatively quickly, but Simon then gets into trouble for returning Joy late to her nurse’s quarters which leads him to scale the building and unexpectedly drop in on another resident. The film ends with Simon and Joy together. We might expect the couple to again appear in the film’s immediate sequel Doctor at Sea (1955), but in this Bogarde’s love interest is played by Brigitte Bardot. Joy returns in Doctor at Large (1957) and significantly this time is training to be a doctor. The relationship has ended by the time of Doctor in Distress (1963) in which Simon is involved with model and actress Delia Mallory (Samantha Eggar). Bogarde’s last ‘Doctor’ film therefore seems to backtrack on the advancement of the third in which his love interest is also a doctor. Overall in Doctor in the House, Simon’s interactions with women show him to be nervous and inexperienced, though a good listener when he picks up on ‘Rigor Mortis’’ lack of interest and finally realises that he and Joy have a lot in common. While Simon is less enthusiastic (and sexist) than some of his friends, he is clearly heterosexual. This is unsurprising given the time, though some of Bogarde’s later roles (including Victim, 1961, and Death in Venice 1971) as well as knowledge of his personal life may cause us to revisit and reinterpret the admittedly throwaway comment about Simon’s ‘mother complex’.

The woman who plays the largest part in the film is nurse Joy Gibson (Muriel Pavlow). Simon and Joy’s relationship gets off to a rocky start when they meet on his first day at the hospital amidst his suitcase embarrassingly spilling open. There are also misunderstandings as when they take a walk in the park each thinks the other is there under duress. This is overcome relatively quickly, but Simon then gets into trouble for returning Joy late to her nurse’s quarters which leads him to scale the building and unexpectedly drop in on another resident. The film ends with Simon and Joy together. We might expect the couple to again appear in the film’s immediate sequel Doctor at Sea (1955), but in this Bogarde’s love interest is played by Brigitte Bardot. Joy returns in Doctor at Large (1957) and significantly this time is training to be a doctor. The relationship has ended by the time of Doctor in Distress (1963) in which Simon is involved with model and actress Delia Mallory (Samantha Eggar). Bogarde’s last ‘Doctor’ film therefore seems to backtrack on the advancement of the third in which his love interest is also a doctor. Overall in Doctor in the House, Simon’s interactions with women show him to be nervous and inexperienced, though a good listener when he picks up on ‘Rigor Mortis’’ lack of interest and finally realises that he and Joy have a lot in common. While Simon is less enthusiastic (and sexist) than some of his friends, he is clearly heterosexual. This is unsurprising given the time, though some of Bogarde’s later roles (including Victim, 1961, and Death in Venice 1971) as well as knowledge of his personal life may cause us to revisit and reinterpret the admittedly throwaway comment about Simon’s ‘mother complex’.

Simon’s lack of confidence which is displayed in relation to women can also be seen in his approach to his medical studies. He is conscientious and kind with patients, but not always sure of himself. This is especially highlighted in scenes with (the admittedly very intimidating) Sir Lancelot Spratt (James Robertson Justice). Robertson Justice loomed large in the series, appearing in all 7 films, though not always as Sir Lancelot. His Captain Hogg in Doctor at Sea nonetheless also combines abrasiveness with a weighty physical and vocal presence – the films well utilise Robertson Justice’s booming voice. In one of Doctor in the House’s most well-known gags, Sir Lancelot pounces on Simon for his inattention during the medical examination of a patient who may need surgery. While Sir Lancelot’s ‘What’s the bleeding time?’ is asking about testing the length of time for a patient’s platelets to function, Simon assumes he is being gruff and responds that ‘It’s ten past ten, Sir’. (The phrase ‘What’s the bleeding time?’ has become so iconic it even provides the title of James Hogg’s 2008 biography of Robertson Justice.) Simon gains medical experience and his delivery of a baby in the middle of winter is especially effective. Simon’s first attendance at a childbirth does not start well (he has bicycle trouble on the way), but he treats the expectant mother (Maureen Pryor) calmly and kindly, so impressing her that she names her new-born after him. We had thought that the scene would be played for laughs, but it is actually very touching.

Simon’s lack of confidence which is displayed in relation to women can also be seen in his approach to his medical studies. He is conscientious and kind with patients, but not always sure of himself. This is especially highlighted in scenes with (the admittedly very intimidating) Sir Lancelot Spratt (James Robertson Justice). Robertson Justice loomed large in the series, appearing in all 7 films, though not always as Sir Lancelot. His Captain Hogg in Doctor at Sea nonetheless also combines abrasiveness with a weighty physical and vocal presence – the films well utilise Robertson Justice’s booming voice. In one of Doctor in the House’s most well-known gags, Sir Lancelot pounces on Simon for his inattention during the medical examination of a patient who may need surgery. While Sir Lancelot’s ‘What’s the bleeding time?’ is asking about testing the length of time for a patient’s platelets to function, Simon assumes he is being gruff and responds that ‘It’s ten past ten, Sir’. (The phrase ‘What’s the bleeding time?’ has become so iconic it even provides the title of James Hogg’s 2008 biography of Robertson Justice.) Simon gains medical experience and his delivery of a baby in the middle of winter is especially effective. Simon’s first attendance at a childbirth does not start well (he has bicycle trouble on the way), but he treats the expectant mother (Maureen Pryor) calmly and kindly, so impressing her that she names her new-born after him. We had thought that the scene would be played for laughs, but it is actually very touching.

Ralph Thomas agreed with Brian McFarlane’s opinion that Pryor’s performance was affecting (McFarlane 1997, pp. 557-558). Bogarde also played the scene with sincerity: he retrospectively commented that he insisted on playing a ‘real doctor’ who never instigated anything funny (McFarlane, 1997, p. 69). Thomas reflected further on this as he claimed that the cast as a whole ‘played it within a very strict, tight limit of believability’ (McFarlane, 1997, p. 557). While this seems true of Bogarde, and indeed Pryor, we were less convinced that this was the case for Donald Sinden (playing Tony Benskin) and to a lesser extent Kenneth More (playing Richard Grimsdyke). It is worth considering Simon in relation to his fellow medical students particularly in terms of the way each approaches his love life and career. Richard is settled with his girlfriend, Stella (Suzanne Cloutier) but incredibly lax about his studies. He has a legacy from his grandmother which offers him a generous stipend while he studies medicine – it is not in his interest to pass his exams and graduate. In fact at the end of the film Stella decides she will study medicine and Richard is thrilled that he will be a ‘kept man’. Tony is not at all settled romantically and sees all nurses as potential targets of his extremely overt attentions. When he inadvertently proposes May (Gudrun Ure), who readily accepts him, he quickly makes sure he is not tied to her by swiftly proposing marriage to all the other nurses as well. Tony’s exam preparation is also ill-organised.

Ralph Thomas agreed with Brian McFarlane’s opinion that Pryor’s performance was affecting (McFarlane 1997, pp. 557-558). Bogarde also played the scene with sincerity: he retrospectively commented that he insisted on playing a ‘real doctor’ who never instigated anything funny (McFarlane, 1997, p. 69). Thomas reflected further on this as he claimed that the cast as a whole ‘played it within a very strict, tight limit of believability’ (McFarlane, 1997, p. 557). While this seems true of Bogarde, and indeed Pryor, we were less convinced that this was the case for Donald Sinden (playing Tony Benskin) and to a lesser extent Kenneth More (playing Richard Grimsdyke). It is worth considering Simon in relation to his fellow medical students particularly in terms of the way each approaches his love life and career. Richard is settled with his girlfriend, Stella (Suzanne Cloutier) but incredibly lax about his studies. He has a legacy from his grandmother which offers him a generous stipend while he studies medicine – it is not in his interest to pass his exams and graduate. In fact at the end of the film Stella decides she will study medicine and Richard is thrilled that he will be a ‘kept man’. Tony is not at all settled romantically and sees all nurses as potential targets of his extremely overt attentions. When he inadvertently proposes May (Gudrun Ure), who readily accepts him, he quickly makes sure he is not tied to her by swiftly proposing marriage to all the other nurses as well. Tony’s exam preparation is also ill-organised.  The non-subtly named Taffy Evans (played by Welshman Donald Houston) seems nice enough, though his focus on Welsh sport is at the expense of his medical studies. Simon is clearly the main character. As well as having more screen time, he has the most sympathetic personality, which develops in confidence in relation to both women and his studies.

The non-subtly named Taffy Evans (played by Welshman Donald Houston) seems nice enough, though his focus on Welsh sport is at the expense of his medical studies. Simon is clearly the main character. As well as having more screen time, he has the most sympathetic personality, which develops in confidence in relation to both women and his studies.

On the surface, the film’s approach to women is reductive. The women are mostly either threatening (Milly and Mrs Groakes for different reasons, Isobel, and the stern Sister Virtue (Jean Taylor-Smith)), arrogant (the only female medical student, Jane, played by Lisa Gastoni) or considered to be unattractive (‘Rigor Mortis’). This is reinforced by some of the male characters’ sexist attitudes towards women, especially Tony’s. The women also exhibit strength, however. The two older women both have authoritative manners and a certain amount of agency: Mrs Groakes manages property, and Sister Virtue is in charge at the hospital. Sexual attractiveness is limited to the younger women, with both Milly and Isobel acting on their desires (even if they frighten Simon in the process) while sister Virtue is revealed to have had a racy past dressing as Lady Godiva. Isobel’

On the surface, the film’s approach to women is reductive. The women are mostly either threatening (Milly and Mrs Groakes for different reasons, Isobel, and the stern Sister Virtue (Jean Taylor-Smith)), arrogant (the only female medical student, Jane, played by Lisa Gastoni) or considered to be unattractive (‘Rigor Mortis’). This is reinforced by some of the male characters’ sexist attitudes towards women, especially Tony’s. The women also exhibit strength, however. The two older women both have authoritative manners and a certain amount of agency: Mrs Groakes manages property, and Sister Virtue is in charge at the hospital. Sexual attractiveness is limited to the younger women, with both Milly and Isobel acting on their desires (even if they frighten Simon in the process) while sister Virtue is revealed to have had a racy past dressing as Lady Godiva. Isobel’ s career as a model may objectify her, but she earns a good living from it, and other women characters also have careers, such as the nurses. Despite the notion that ‘Rigor Mortis’ is unattractive, she still fails to fall at Simon’s feet. The two most rounded female characters are Stella and Joy. Like ‘Rigor Mortis’ Joy does not just submit to Simon’s charms, and Stella’s relationship with Richard seems quite equable with her deciding to become a doctor near the film’s close. Significantly, Joy re-emerges as a trainee doctor in Doctor at Large.

s career as a model may objectify her, but she earns a good living from it, and other women characters also have careers, such as the nurses. Despite the notion that ‘Rigor Mortis’ is unattractive, she still fails to fall at Simon’s feet. The two most rounded female characters are Stella and Joy. Like ‘Rigor Mortis’ Joy does not just submit to Simon’s charms, and Stella’s relationship with Richard seems quite equable with her deciding to become a doctor near the film’s close. Significantly, Joy re-emerges as a trainee doctor in Doctor at Large.

It is tempting to attribute some of this more progressive approach to women to the film’s female producer, Betty E. Box. While this would be reductive, as well as difficult to prove, it is worth considering Box’s role a little more. She began producing films in the late 1940s and had taken charge of more than 15 films by the time of Doctor in the House. Her very presence as a powerful woman off screen was unusual at the time. Box’s status as a woman in a man’s world is directly commented on by Justine Ashby’s 2001 PhD thesis ‘Odd Women Out’ which examines the careers of Box and her sister-in-law the director Muriel Box. Betty E. Box played an important role in making sure the first Doctor film made it to the screen. Box relates how she read Gordon’s novel on a train and thought it would work well on the big screen (McFarlane, 1997, p. 87). She also commented on the large role she played in casting. After finding out that her first choice, Robert Morley, was far too expensive, Box secured Robertson Justice as he ‘doesn’t have to do very much except be himself’ (McFarlane, 1997, p. 87). Box noted that the downside of the film’s huge success meant that she became trapped into producing the sequels (McFarlane, 1997, p 86). Box still negotiated opportunities to produce other projects. She often collaborated with Doctor director Ralph Thomas, and at several of their films starred Bogarde – for example A Tale of Two Cities (1958). (For more on Box, see Ashby’s chapter on Betty E. Box in Ashby and Andrew Higson’s 2000 edited volume British Cinema, Past and Present.)

It is tempting to attribute some of this more progressive approach to women to the film’s female producer, Betty E. Box. While this would be reductive, as well as difficult to prove, it is worth considering Box’s role a little more. She began producing films in the late 1940s and had taken charge of more than 15 films by the time of Doctor in the House. Her very presence as a powerful woman off screen was unusual at the time. Box’s status as a woman in a man’s world is directly commented on by Justine Ashby’s 2001 PhD thesis ‘Odd Women Out’ which examines the careers of Box and her sister-in-law the director Muriel Box. Betty E. Box played an important role in making sure the first Doctor film made it to the screen. Box relates how she read Gordon’s novel on a train and thought it would work well on the big screen (McFarlane, 1997, p. 87). She also commented on the large role she played in casting. After finding out that her first choice, Robert Morley, was far too expensive, Box secured Robertson Justice as he ‘doesn’t have to do very much except be himself’ (McFarlane, 1997, p. 87). Box noted that the downside of the film’s huge success meant that she became trapped into producing the sequels (McFarlane, 1997, p 86). Box still negotiated opportunities to produce other projects. She often collaborated with Doctor director Ralph Thomas, and at several of their films starred Bogarde – for example A Tale of Two Cities (1958). (For more on Box, see Ashby’s chapter on Betty E. Box in Ashby and Andrew Higson’s 2000 edited volume British Cinema, Past and Present.)

House and Doctor at Large starring Richard Briers. The first of several UK television series started the next year, this again beginning with Doctor in the House, which ran until 1970. The series did not share characters with the film series, or involve Box and Thomas, but had constancy with its own characters and actors in the sequels, at Large (1971), in Charge (1972-3), at Sea (1974), on the Go (1975-77), Down Under (1979) and the much later at the Top (1991).

House and Doctor at Large starring Richard Briers. The first of several UK television series started the next year, this again beginning with Doctor in the House, which ran until 1970. The series did not share characters with the film series, or involve Box and Thomas, but had constancy with its own characters and actors in the sequels, at Large (1971), in Charge (1972-3), at Sea (1974), on the Go (1975-77), Down Under (1979) and the much later at the Top (1991).

We also commented on the fact that the comedy in the Doctor series of films pre-dated similar humour in some of the Carry On Series. The Carry On series began with Carry on Sergeant in 1958 and ended with the last official film Carry on Columbus (1992), though there were also TV shows and there is continued talk of a revival. All the Carry Ons were produced by Peter Rogers, Doctor producer Betty Box’s husband, and directed by Gerald Thomas – the brother of Doctor director Ralph. (The Thomas brothers co-directed Regardless in 1961 and Cruising in 62). This signals significant overlap. Saucy Carry On humour (largely characterised by innuendo and commentary on gender relations) can be traced back to music hall, seaside postcards and the like. But the fact that the series had several medical instalments is worth further comment. They comprise the films Nurse (1959), Doctor (1967), Again Doctor (1969) and Matron (1972). The Carry On medical cycle therefore started after the first 3 Doctor films had been released, and after Bogarde left the series (though he chose to return once for Doctor in Distress in 1963). Ralph Thomas asserted that the Doctor films were the first to poke fun at the medical profession (McFarlane, 1997, p. 557) and perhaps paved the way for medical humour in the Carry Ons. The large (8 year) gap between the first and second medical Carry On, and the fact that there was only 1 Doctor film after this, suggests that the medical Carry Ons briefly took the place previously occupied by the Doctor films. The medical Carry Ons only returned for one instalment after the Doctor series ended, though, with medical humour more evident in the various Doctor series on television throughout most of the 1970s.

We also commented on the fact that the comedy in the Doctor series of films pre-dated similar humour in some of the Carry On Series. The Carry On series began with Carry on Sergeant in 1958 and ended with the last official film Carry on Columbus (1992), though there were also TV shows and there is continued talk of a revival. All the Carry Ons were produced by Peter Rogers, Doctor producer Betty Box’s husband, and directed by Gerald Thomas – the brother of Doctor director Ralph. (The Thomas brothers co-directed Regardless in 1961 and Cruising in 62). This signals significant overlap. Saucy Carry On humour (largely characterised by innuendo and commentary on gender relations) can be traced back to music hall, seaside postcards and the like. But the fact that the series had several medical instalments is worth further comment. They comprise the films Nurse (1959), Doctor (1967), Again Doctor (1969) and Matron (1972). The Carry On medical cycle therefore started after the first 3 Doctor films had been released, and after Bogarde left the series (though he chose to return once for Doctor in Distress in 1963). Ralph Thomas asserted that the Doctor films were the first to poke fun at the medical profession (McFarlane, 1997, p. 557) and perhaps paved the way for medical humour in the Carry Ons. The large (8 year) gap between the first and second medical Carry On, and the fact that there was only 1 Doctor film after this, suggests that the medical Carry Ons briefly took the place previously occupied by the Doctor films. The medical Carry Ons only returned for one instalment after the Doctor series ended, though, with medical humour more evident in the various Doctor series on television throughout most of the 1970s.

The Doctor and Carry On series therefore share humour in medical situations as well as connections with their behind-the-scenes personnel. Links are also evident to audiences since some cast members appear in films from both series. Doctor in the House’s ‘Rigor Mortis’ actress, Joan Sims, appeared in a further 4 films in the Doctor series (Sea, Love, Clover, and Trouble, essaying different characters each time). She was also a stalwart of the Carry On series, starring in 24 of the total 31 films, including all 4 of the medical instalments. Joan Hickson appeared in the Doctor films House, Sea and Love and was a ward sister in Carry on Nurse. Shirley Eaton was in two Doctor films (House and Large) and, like Hickson, played a nurse in the first Carry on medical film.

The Doctor and Carry On series therefore share humour in medical situations as well as connections with their behind-the-scenes personnel. Links are also evident to audiences since some cast members appear in films from both series. Doctor in the House’s ‘Rigor Mortis’ actress, Joan Sims, appeared in a further 4 films in the Doctor series (Sea, Love, Clover, and Trouble, essaying different characters each time). She was also a stalwart of the Carry On series, starring in 24 of the total 31 films, including all 4 of the medical instalments. Joan Hickson appeared in the Doctor films House, Sea and Love and was a ward sister in Carry on Nurse. Shirley Eaton was in two Doctor films (House and Large) and, like Hickson, played a nurse in the first Carry on medical film.

Some male actors were also seen in both series. Leslie Phillips took on a main role as in the Doctor series during Bogarde’s absence, starring in Love, Clover and Trouble. His 4 Carry Ons included Carry on Nurse, in which his character’s name, Jack Bell, helped to provide one of his catchphrases ‘Ding Dong!’ when glimpsing an attractive woman. Connections between the two series are furthered by a portrait of James Robertson Justice (presumably as Sir Lancelot Spratt) appearing in Carry on Doctor. He impressively manages to somehow cross the boundary between the two film series’ worlds.

Some male actors were also seen in both series. Leslie Phillips took on a main role as in the Doctor series during Bogarde’s absence, starring in Love, Clover and Trouble. His 4 Carry Ons included Carry on Nurse, in which his character’s name, Jack Bell, helped to provide one of his catchphrases ‘Ding Dong!’ when glimpsing an attractive woman. Connections between the two series are furthered by a portrait of James Robertson Justice (presumably as Sir Lancelot Spratt) appearing in Carry on Doctor. He impressively manages to somehow cross the boundary between the two film series’ worlds.

One of our group was from the US and found some the situations present and accents used in Doctor in the House mystifying. (We offered to turn on the subtitles, but were not sure if some of the vocalisations, especially by Sinden, could be accurately conveyed in language!) This caused us to consider not just the film’s place in British culture (and it does seem very much based in British culture) but how it was seen in US on its release on the 2nd of February 1955. Nearly a year before this date, at the time of the film’s release in the UK, US trade paper Variety’s London reviewer opined that the film’s ‘marquee appeal may be restricted across the Atlantic’ (7th April 1954, p. 6). US trade papers on the film’s US release were generally positive, with Motion Picture Daily noting that while the cast may not be well-known to American audiences, it was likely to do better than other UK imports (18th February 1955, p. 6). The Independent Film Journal (19th February 1955, p. 29) and the Independent Film Bulletin (21st February 1955, p. 14) similarly commenting on the unfamiliarity of the cast. They both downplay Bogarde’s role by noting the presence of Kenneth More and Kay Kendall who were in Henry Cornelius’ 1953 film Genevieve which was successful in the US on its release. The Independent Film Bulletin considers that Doctor in the House ‘lacks the universal humor of the popular Genevieve’ but ‘has plenty to amuse fanciers of British humor’. This suggests that its humour is peculiarly British, and that this was not the case with Genevieve.

One of our group was from the US and found some the situations present and accents used in Doctor in the House mystifying. (We offered to turn on the subtitles, but were not sure if some of the vocalisations, especially by Sinden, could be accurately conveyed in language!) This caused us to consider not just the film’s place in British culture (and it does seem very much based in British culture) but how it was seen in US on its release on the 2nd of February 1955. Nearly a year before this date, at the time of the film’s release in the UK, US trade paper Variety’s London reviewer opined that the film’s ‘marquee appeal may be restricted across the Atlantic’ (7th April 1954, p. 6). US trade papers on the film’s US release were generally positive, with Motion Picture Daily noting that while the cast may not be well-known to American audiences, it was likely to do better than other UK imports (18th February 1955, p. 6). The Independent Film Journal (19th February 1955, p. 29) and the Independent Film Bulletin (21st February 1955, p. 14) similarly commenting on the unfamiliarity of the cast. They both downplay Bogarde’s role by noting the presence of Kenneth More and Kay Kendall who were in Henry Cornelius’ 1953 film Genevieve which was successful in the US on its release. The Independent Film Bulletin considers that Doctor in the House ‘lacks the universal humor of the popular Genevieve’ but ‘has plenty to amuse fanciers of British humor’. This suggests that its humour is peculiarly British, and that this was not the case with Genevieve.

The two trade papers also interestingly comment on the specific exhibition circumstances: it is thought that Doctor in the House would do well in ‘art house’ cinemas (perhaps because of its very British flavour) but if correctly exploited could also succeed in the ‘general market’. The Chicago Daily Tribune (21st March 1955, p. B15) reinforces the view that the film would be well-received by the general public (‘I think you’ll have fun with this import’) as the newspaper’s readership was likely to be general rather than specialist. Another newspaper, the New York Times (18th February 1955, p. 18), implies that part of this appeal is due to the film’s innovative stance in poking fun at the medical profession, an opinion also advanced by the April 1955 issue of fan magazine Photoplay (p. 30). This recalls the director Ralph Thomas’s comment referred to in the section considering the film’s relationship to the Carry On series. While medical humour may have crossed the Atlantic at the time (despite the notion that Doctor in the House’s humour was less universal than Genevieve’s), the fact that our research group member from the US was puzzled suggests that the temporal boundary was more difficult to traverse. We wondered if her lack of exposure to Carry On-style humour was partly related to the change in television viewing habits. 15 years ago, live TV was perhaps the main way of seeing films, even though films were available to view on DVD. The rise in On Demand means that more recently viewers have had far more content to choose from and in many ways film-viewing has become less communal. We especially appreciate that the melodrama research group screenings give us an opportunity to gather together to watch films and share our diverse points of view.

The two trade papers also interestingly comment on the specific exhibition circumstances: it is thought that Doctor in the House would do well in ‘art house’ cinemas (perhaps because of its very British flavour) but if correctly exploited could also succeed in the ‘general market’. The Chicago Daily Tribune (21st March 1955, p. B15) reinforces the view that the film would be well-received by the general public (‘I think you’ll have fun with this import’) as the newspaper’s readership was likely to be general rather than specialist. Another newspaper, the New York Times (18th February 1955, p. 18), implies that part of this appeal is due to the film’s innovative stance in poking fun at the medical profession, an opinion also advanced by the April 1955 issue of fan magazine Photoplay (p. 30). This recalls the director Ralph Thomas’s comment referred to in the section considering the film’s relationship to the Carry On series. While medical humour may have crossed the Atlantic at the time (despite the notion that Doctor in the House’s humour was less universal than Genevieve’s), the fact that our research group member from the US was puzzled suggests that the temporal boundary was more difficult to traverse. We wondered if her lack of exposure to Carry On-style humour was partly related to the change in television viewing habits. 15 years ago, live TV was perhaps the main way of seeing films, even though films were available to view on DVD. The rise in On Demand means that more recently viewers have had far more content to choose from and in many ways film-viewing has become less communal. We especially appreciate that the melodrama research group screenings give us an opportunity to gather together to watch films and share our diverse points of view.

Do log in to comment, or email me on sp761@kent.ac.uk and let me know that you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.