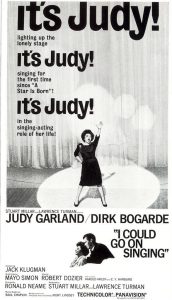

Our discussion on I Could Go On Singing included consideration of melodramatic aspects such as Jenny Bowman (Judy Garland) as a suffering woman and the genre of maternal melodrama; Judy Garland’s star entrance and moments of spectacle which privilege her; the film’s music: especially the way the songs commented, or neglected to comment, on the film’s action and themes; the relationship between the character Jenny Bowman and Garland’s own screen and star images; Dirk Bogarde’s character David Donne; Bogarde as a supporting star to Garland both on and off the screen.

The film was screened as part of our exploration of the many different facets of melodrama in films starring Dirk Bogarde. While Bogarde retains above-the-title billing, much of our discussion unsurprisingly focused on Judy Garland’s character, Jenny Bowman. We especially noted that the suffering which is central to many melodramas is evident in three parts of Jenny’s identity: as a performer, as a woman, and as a mother.

Revealingly, the original title for I Could Go On Singing was The Lonely Stage. The pressure on a performer in a one man or woman musical show is immense: he or she must be in the right place (often far from home) at the right time, fully rehearsed, and note-perfect. He or she also has to match the audience’s expectations of him or her as existing just for them in that moment. Jenny experiences problems towards the end of the film when she becomes drunk due to emotional distress and does not want to perform. Nonetheless, the show cannot go on without her, and she does not only appear as promised, but maintains an on-stage façade of being bright and fun.

Revealingly, the original title for I Could Go On Singing was The Lonely Stage. The pressure on a performer in a one man or woman musical show is immense: he or she must be in the right place (often far from home) at the right time, fully rehearsed, and note-perfect. He or she also has to match the audience’s expectations of him or her as existing just for them in that moment. Jenny experiences problems towards the end of the film when she becomes drunk due to emotional distress and does not want to perform. Nonetheless, the show cannot go on without her, and she does not only appear as promised, but maintains an on-stage façade of being bright and fun.

The well-worn trope of a performer suffering behind the scenes has perhaps be shown to its best effect in the several versions of A Star is Born. The narrative sees a young female performer falling in love with an established star, and then eclipsing him. This leads to suffering for them both. Following William A. Wellman’s first iteration (in 1937, starring Janet Gaynor and Fredric March) emphasis moved to musical versions. George Cukor directed Judy Garland herself alongside James Mason in 1954. Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson were next in Frank Pierson’s 1976 film, and just recently Lady Gaga appeared opposite Bradley Cooper in his 2018 production.

The well-worn trope of a performer suffering behind the scenes has perhaps be shown to its best effect in the several versions of A Star is Born. The narrative sees a young female performer falling in love with an established star, and then eclipsing him. This leads to suffering for them both. Following William A. Wellman’s first iteration (in 1937, starring Janet Gaynor and Fredric March) emphasis moved to musical versions. George Cukor directed Judy Garland herself alongside James Mason in 1954. Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson were next in Frank Pierson’s 1976 film, and just recently Lady Gaga appeared opposite Bradley Cooper in his 2018 production.

Jenny’s suffering as a woman is expressed in terms of her romantic and familial relationships. She tells ex-lover David that she has been lonely since their relationship ended, even (in fact especially) during her two failed marriages. This is what partly fuels her desire to see Matt (Gregory Phillips), the son she left his father, David, to bring up 12 years ago. It also gives Jenny an excuse to see David again. Although David agrees to mother and son meeting once – under his supervision during Matt’s rugby match at boarding school – Jenny craves further contact. Predictably, Jenny’s precarious life as a performer (rehearsals, late performances, a focus on what is essential for her career success – herself) leaves little room for Matt. When they spend time together at her hotel in London she sleeps late, and they miss sight-seeing opportunities. Jenny, and David, also selfishly argue within Matt’s hearing, leading to him discovering the truth about his parentage – that David is

Jenny’s suffering as a woman is expressed in terms of her romantic and familial relationships. She tells ex-lover David that she has been lonely since their relationship ended, even (in fact especially) during her two failed marriages. This is what partly fuels her desire to see Matt (Gregory Phillips), the son she left his father, David, to bring up 12 years ago. It also gives Jenny an excuse to see David again. Although David agrees to mother and son meeting once – under his supervision during Matt’s rugby match at boarding school – Jenny craves further contact. Predictably, Jenny’s precarious life as a performer (rehearsals, late performances, a focus on what is essential for her career success – herself) leaves little room for Matt. When they spend time together at her hotel in London she sleeps late, and they miss sight-seeing opportunities. Jenny, and David, also selfishly argue within Matt’s hearing, leading to him discovering the truth about his parentage – that David is  his real, and not adoptive father, and Jenny his mother. Jenny’s sadness that she cannot be the mother she wants to be leads to her going on the drinking binge which jeopardises her career at the end of the film, revealing the impact of the personal on the professional.

his real, and not adoptive father, and Jenny his mother. Jenny’s sadness that she cannot be the mother she wants to be leads to her going on the drinking binge which jeopardises her career at the end of the film, revealing the impact of the personal on the professional.

I Could Go on Singing therefore comments on a woman not being able to have both a family and a career. Such notions still exist today, though they were even more prevalent at the time of the film’s production. Significantly, we thought that the film demonstrated that David’s relationship with Matt has also suffered due to his being away for long periods due to his work as an Ear, Nose and Throat specialist. David has a warm and jokey relationship with Matt and he is clearly protective of him. But father and son do not spend much time together – not only is Matt away at boarding school (presented on screen by King’s School in Canterbury) during term time, but it is mentioned that he will also be spending some of his holidays with his Aunt in Kent. We should be wary, however, of viewing the father/son relationship through a modern lens. David certainly has a closer relationship with Matt than Jenny does, and one which was probably viewed as typical of the time.

I Could Go on Singing therefore comments on a woman not being able to have both a family and a career. Such notions still exist today, though they were even more prevalent at the time of the film’s production. Significantly, we thought that the film demonstrated that David’s relationship with Matt has also suffered due to his being away for long periods due to his work as an Ear, Nose and Throat specialist. David has a warm and jokey relationship with Matt and he is clearly protective of him. But father and son do not spend much time together – not only is Matt away at boarding school (presented on screen by King’s School in Canterbury) during term time, but it is mentioned that he will also be spending some of his holidays with his Aunt in Kent. We should be wary, however, of viewing the father/son relationship through a modern lens. David certainly has a closer relationship with Matt than Jenny does, and one which was probably viewed as typical of the time.

Jenny’s relationship with Matt is similar to, but also different from, other maternal melodramas the group has previously screened. In both Stella Dallas (1937, King Vidor) and The Old Maid (1939, Edmund Golding) the mother loves her child deeply but considers that she would be better off without her as a mother. In the former case this is due to the mother’s low-

Jenny’s relationship with Matt is similar to, but also different from, other maternal melodramas the group has previously screened. In both Stella Dallas (1937, King Vidor) and The Old Maid (1939, Edmund Golding) the mother loves her child deeply but considers that she would be better off without her as a mother. In the former case this is due to the mother’s low- class status, and in the latter to the fact she is unmarried. (You can find more information on our responses to these films by searching the blog for the film titles.) I Could Go On Singing is a less extreme maternal melodrama in terms of Jenny’s suffering and sacrifice. Similarly, her child’s suffering is not brought about by parental cruelty or malice: Jenny and David could both handle their relationships with their son better, but this is not deliberate.

class status, and in the latter to the fact she is unmarried. (You can find more information on our responses to these films by searching the blog for the film titles.) I Could Go On Singing is a less extreme maternal melodrama in terms of Jenny’s suffering and sacrifice. Similarly, her child’s suffering is not brought about by parental cruelty or malice: Jenny and David could both handle their relationships with their son better, but this is not deliberate.

Our discussion of Garland also commented on her introduction. She is treated to a star entrance. Her figure, at first not especially recognisable, alights from a car and she proceeds to walk, with her back to camera, to a front door. This delays our first proper glimpse of Garland. The scene cuts to the well-lit interior of the house as a woman descend the stairs to answer the door and greet the visitor. Garland is framed by an internal window, soon proceeding into the house and becoming recognisable to the audience. She then mounts the stairs to meet the advancing David.

Our discussion of Garland also commented on her introduction. She is treated to a star entrance. Her figure, at first not especially recognisable, alights from a car and she proceeds to walk, with her back to camera, to a front door. This delays our first proper glimpse of Garland. The scene cuts to the well-lit interior of the house as a woman descend the stairs to answer the door and greet the visitor. Garland is framed by an internal window, soon proceeding into the house and becoming recognisable to the audience. She then mounts the stairs to meet the advancing David.

Other moments which privilege Garland are more striking. Many of these relate to the staging of her songs. Garland’s rendition of I Could Go On Singing plays over the opening credits which are superimposed on abstract blurred coloured spotlights. I am the Monarch of the Sea is sung by Garland, and others, after Matt and his school classmates’ production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. Later on, Jenny performs Hello Bluebird, It Never Was You, By Myself, and I Could Go on Singing on stage.

Other moments which privilege Garland are more striking. Many of these relate to the staging of her songs. Garland’s rendition of I Could Go On Singing plays over the opening credits which are superimposed on abstract blurred coloured spotlights. I am the Monarch of the Sea is sung by Garland, and others, after Matt and his school classmates’ production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s HMS Pinafore. Later on, Jenny performs Hello Bluebird, It Never Was You, By Myself, and I Could Go on Singing on stage.

We commented on the placement of these three songs in the narrative and how the lyrics related to the actions and emotions present in the film. The joyous Hello Bluebird appropriately occurs just after Jenny has learned, in contrast to a telegram she has just received, that her son Matt can in fact attend her concert. The lyrics of It Never Was You concern a disappointed woman who has searched for, but not yet found, a lost lover. While this may be seen to relate to Jenny’s relationship with David, the parallels in the next two songs are more conspicuous. By Myself is also about suffering connected to expectations of love not being met. But its highs and lows seem more extreme, more melodramatic. Its lyrics declare that ‘this is the end of romance’ and reject the notion of love as ‘an overrated past time’; it is ‘only a dance’. While it is clearly not meant to be a song about recent or current events (Jenny is not improvising the song on the spot) its timing is significant: it occurs just after Jenny’s heated argument with David when Matt finds out the truth about his parentage. There is also defiance in By Myself’s lyrics, despite the emphasis on being alone. The singer vows to ‘face the unknown, build a world of my own’ and is ‘sure that I am old enough to fly alone’. This suits Jenny’s action at the song’s completion: she strides off the stage and startles her manager, George (Jack Klugman) by demanding answers about the possibility of her gaining parental access to Matt.

We commented on the placement of these three songs in the narrative and how the lyrics related to the actions and emotions present in the film. The joyous Hello Bluebird appropriately occurs just after Jenny has learned, in contrast to a telegram she has just received, that her son Matt can in fact attend her concert. The lyrics of It Never Was You concern a disappointed woman who has searched for, but not yet found, a lost lover. While this may be seen to relate to Jenny’s relationship with David, the parallels in the next two songs are more conspicuous. By Myself is also about suffering connected to expectations of love not being met. But its highs and lows seem more extreme, more melodramatic. Its lyrics declare that ‘this is the end of romance’ and reject the notion of love as ‘an overrated past time’; it is ‘only a dance’. While it is clearly not meant to be a song about recent or current events (Jenny is not improvising the song on the spot) its timing is significant: it occurs just after Jenny’s heated argument with David when Matt finds out the truth about his parentage. There is also defiance in By Myself’s lyrics, despite the emphasis on being alone. The singer vows to ‘face the unknown, build a world of my own’ and is ‘sure that I am old enough to fly alone’. This suits Jenny’s action at the song’s completion: she strides off the stage and startles her manager, George (Jack Klugman) by demanding answers about the possibility of her gaining parental access to Matt.

I Could Go on Singing is arguably the film’s most important song. It not only frames the film – it is present over the opening credits, and on screen at the end after Jenny has been propped up by David – but is the only one expressly written for the film. It connects Jenny’s desire to sing (which is of course necessary to her career success) to being in love. The song’s claim that ‘When I see your eyes I go all out, I must vocalise till you shout “enough already”’ certainly supports its statement

I Could Go on Singing is arguably the film’s most important song. It not only frames the film – it is present over the opening credits, and on screen at the end after Jenny has been propped up by David – but is the only one expressly written for the film. It connects Jenny’s desire to sing (which is of course necessary to her career success) to being in love. The song’s claim that ‘When I see your eyes I go all out, I must vocalise till you shout “enough already”’ certainly supports its statement  that ‘love does funny things when it hits you this way’. Memorably it avows that the singer could carry on until the ‘cows come home’, reinforcing this with an expression about an even less likely occurrence: the moon turning pink. It is worth considering a matter central to the film: who is the object of Jenny’s affections? Is it David, Matt, herself, or possibly even her audience?

that ‘love does funny things when it hits you this way’. Memorably it avows that the singer could carry on until the ‘cows come home’, reinforcing this with an expression about an even less likely occurrence: the moon turning pink. It is worth considering a matter central to the film: who is the object of Jenny’s affections? Is it David, Matt, herself, or possibly even her audience?

Differences between the way these songs were filmed (and especially how these emphasised Jenny’s status as a performer) were also commented on. The Monarch of the Sea fittingly includes no obvious means of amplification since it is an informal gathering around a piano. By contrast, the technology Jenny needs to deliver Hello Bluebird to a theatre full of people is not just visible, but made noticeable. Jenny takes the microphone off its stand as she sings ‘I’m back home today’. This visually underlines the importance of her statement (the stage is her home) but also allows her to demonstrate this by actively moving around the space. The microphone lead trails with Jenny as the camera follows her walking across the stage. The other half of the performing equation – the audience – is also depicted. As well as crowd shots at the beginning and end of the song, cutting away to the audience during it means that Jenny can be re-framed in a longer shot which further conveys her status as performer.

Differences between the way these songs were filmed (and especially how these emphasised Jenny’s status as a performer) were also commented on. The Monarch of the Sea fittingly includes no obvious means of amplification since it is an informal gathering around a piano. By contrast, the technology Jenny needs to deliver Hello Bluebird to a theatre full of people is not just visible, but made noticeable. Jenny takes the microphone off its stand as she sings ‘I’m back home today’. This visually underlines the importance of her statement (the stage is her home) but also allows her to demonstrate this by actively moving around the space. The microphone lead trails with Jenny as the camera follows her walking across the stage. The other half of the performing equation – the audience – is also depicted. As well as crowd shots at the beginning and end of the song, cutting away to the audience during it means that Jenny can be re-framed in a longer shot which further conveys her status as performer.

It was noted that the obvious use of technology contrasts with It Never Was You, By Myself, and I Could Go On Singing. These are more in keeping with the traditional film musical which erases the amplification apparatus, despite often pretending that songs are performed ‘live’. Such invisible technology shifts the film from stage to cinema spectacle. They are also noticeably unlike footage of Garland’s concert and TV performances which show her with a microphone in her hand.

These songs also show the audience, and Jenny’s status as performer, to differing degrees. Garland’s performance of It Never Was You (which was apparently sung live on stage) appears to have been achieved in one take. This focuses entirely on Garland, closing in on her from a straight ahead shot until it moves to show her in profile. The filming of By Myself also does not emphasise the audience’s presence. However, unmotivated cuts seem to comment directly on how the stage and film audiences should view Jenny. The camera switches to a longer shot as the song’s lyric emphasise that the singer is ‘alone’. Jenny is seen as a small figure on a dark stage lit by only a spotlight.

These songs also show the audience, and Jenny’s status as performer, to differing degrees. Garland’s performance of It Never Was You (which was apparently sung live on stage) appears to have been achieved in one take. This focuses entirely on Garland, closing in on her from a straight ahead shot until it moves to show her in profile. The filming of By Myself also does not emphasise the audience’s presence. However, unmotivated cuts seem to comment directly on how the stage and film audiences should view Jenny. The camera switches to a longer shot as the song’s lyric emphasise that the singer is ‘alone’. Jenny is seen as a small figure on a dark stage lit by only a spotlight.

I Could Go On Singing, like It Never Was You and By Myself, suggests that Jenny is not using unnatural means to deliver the necessary amplification. However, in common with the staging of Hello Bluebird, it focuses on the on-screen audience. Furthermore, it places Jenny (and Garland) in the context of her audience; several shots seem to be taken from the wings, depicting Jenny and the audience in the same frame and supporting interpretations of this being where Jenny (and Garland) belongs.

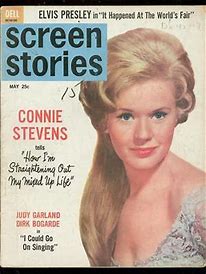

This important relationship between Jenny and her theatre audience is mirrored in that of Garland and the film audience. US trade magazine Box Office’s review and exploitips note that I Could Go on Singing is the first opportunity in nearly a decade to see Garland singing in character. A behind-the-scenes piece on the film in the May 1963 issue of US magazine Screen Stories compares her role as Jenny to those Garland played in earlier films. It is claimed that this is the first time Garland has smoked on the big screen or seemed the worse for drink; meanwhile Garland herself supposedly comments that this is her first ‘really adult love affair’ (p. 53). Implications that her recent roles were somehow child-like are not wholly accurate. Following Garland’s role in A Star is Born, Garland appeared in the hard-hitting film dramas Judgment at Nuremberg (1961, Stanley Kramer) and A Child is Waiting (1963, John Cassavetes). But such statements importantly reposition expectations about Garland’s current screen image. While

This important relationship between Jenny and her theatre audience is mirrored in that of Garland and the film audience. US trade magazine Box Office’s review and exploitips note that I Could Go on Singing is the first opportunity in nearly a decade to see Garland singing in character. A behind-the-scenes piece on the film in the May 1963 issue of US magazine Screen Stories compares her role as Jenny to those Garland played in earlier films. It is claimed that this is the first time Garland has smoked on the big screen or seemed the worse for drink; meanwhile Garland herself supposedly comments that this is her first ‘really adult love affair’ (p. 53). Implications that her recent roles were somehow child-like are not wholly accurate. Following Garland’s role in A Star is Born, Garland appeared in the hard-hitting film dramas Judgment at Nuremberg (1961, Stanley Kramer) and A Child is Waiting (1963, John Cassavetes). But such statements importantly reposition expectations about Garland’s current screen image. While  Garland will once again be singing, she will not be playing the less adult roles of her early musicals. This was perhaps necessary since other than these earlier film musicals, Garland’s more regular concert performances were occasionally televised, meaning that audiences would have been more familiar with her singing ‘as herself’.

Garland will once again be singing, she will not be playing the less adult roles of her early musicals. This was perhaps necessary since other than these earlier film musicals, Garland’s more regular concert performances were occasionally televised, meaning that audiences would have been more familiar with her singing ‘as herself’.

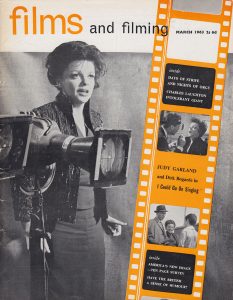

We can never know the ‘real’ person of the star, only what is said to be true about them (his or her star image). A star’s star image is often similar his or her screen image (the characters he or she plays), but this is especially true in Garland talking on the role of world-famous concert singer Jenny Bowman. The close relationship between Jenny and Judy was commented on by the March 1963 issue of UK film magazine Films and Filming. Richard Whitehall opines that the film is a ‘demonstration of the ultimate in star quality with an artist moulding the material to her talents’ and that Garland ‘is the film’ (p. 34).

We can never know the ‘real’ person of the star, only what is said to be true about them (his or her star image). A star’s star image is often similar his or her screen image (the characters he or she plays), but this is especially true in Garland talking on the role of world-famous concert singer Jenny Bowman. The close relationship between Jenny and Judy was commented on by the March 1963 issue of UK film magazine Films and Filming. Richard Whitehall opines that the film is a ‘demonstration of the ultimate in star quality with an artist moulding the material to her talents’ and that Garland ‘is the film’ (p. 34).

Some in the melodrama group thought that the film’s mining of Garland’s star image was exploitative. It is, however, common practice, and we should be wary of denying her agency in choosing to make the film. Such views are of course coloured by our knowledge that this was Garland’s last film and that she died young, 6 years after its release. Contemporary audiences would not have been aware of these facts. Extratextual material at the time drew parallels between Judy and Jenny as singers, but also emphasised Garland’s good relationship with her children. The aforementioned March 1963 Screen Stories article displays a prominent photograph of Garland celebrating her birthday with a cake, alongside her 3 children, as well as her co-stars Bogarde and Phillips. The text of the piece also quotes Garland on the ridiculousness of this film constituting her first adult love affair, when she has ‘3 wonderful children in real life’. She has brought them to London for filming (Lorna and Joey were even extras in the film) and the article closes with an anecdote about the family sight-seeing (p. 53).

Some in the melodrama group thought that the film’s mining of Garland’s star image was exploitative. It is, however, common practice, and we should be wary of denying her agency in choosing to make the film. Such views are of course coloured by our knowledge that this was Garland’s last film and that she died young, 6 years after its release. Contemporary audiences would not have been aware of these facts. Extratextual material at the time drew parallels between Judy and Jenny as singers, but also emphasised Garland’s good relationship with her children. The aforementioned March 1963 Screen Stories article displays a prominent photograph of Garland celebrating her birthday with a cake, alongside her 3 children, as well as her co-stars Bogarde and Phillips. The text of the piece also quotes Garland on the ridiculousness of this film constituting her first adult love affair, when she has ‘3 wonderful children in real life’. She has brought them to London for filming (Lorna and Joey were even extras in the film) and the article closes with an anecdote about the family sight-seeing (p. 53).

Of course we also discussed Bogarde’s role supporting Garland – both on screen and off. The film does not afford Bogarde the opportunities to show both the sensitive and villainous qualities we have noted in previous screenings (Esther Waters, Hunted, Libel, and The Singer not the Song). Our knowledge of David does develop from his first appearance on screen to his last, however. The way the pair first interacted was especially praised. There was formality and doctorly concern in his manner, while it was only slowly revealed that they have previously known one another and indeed have a son together. Warmth between David and Matt allow for Bogarde to play the nice guy, who is protective of his son, but still willing to give Jenny a chance to share their son. Bogarde is especially effective in the scene in which he and Jenny clash over her desire to tell Matt the truth. His initial outburst of anger is followed by crestfallen regret when he sees Matt and realises that he has heard the truth.

Of course we also discussed Bogarde’s role supporting Garland – both on screen and off. The film does not afford Bogarde the opportunities to show both the sensitive and villainous qualities we have noted in previous screenings (Esther Waters, Hunted, Libel, and The Singer not the Song). Our knowledge of David does develop from his first appearance on screen to his last, however. The way the pair first interacted was especially praised. There was formality and doctorly concern in his manner, while it was only slowly revealed that they have previously known one another and indeed have a son together. Warmth between David and Matt allow for Bogarde to play the nice guy, who is protective of his son, but still willing to give Jenny a chance to share their son. Bogarde is especially effective in the scene in which he and Jenny clash over her desire to tell Matt the truth. His initial outburst of anger is followed by crestfallen regret when he sees Matt and realises that he has heard the truth.

The final scenes show yet more dimensions as David tends to Jenny’s wounds and promises to stay with her as long as she needs him. There was debate about the fact that David disappears while Jenny is singing I Could Go On Singing on stage at the end of the film. Some thought that his previous words had therefore meant nothing and that he had never intended to stay with Jenny. Others were of the opinion that the defiant way in which Garland performs this final song – which after all is about someone who can keep singing until the moon turns pink – showed that she had sufficiently recovered. This view is supported by the end of the fiction-version of the story which appeared in the May 1963 issue of US fan magazine Screen Stories:

” “I’ll stay,” he said.

“How long?”

“Until you can stand by yourself again,” he said….

She limped onto the great empty stage in her street clothes, late, but willing to sing. The audience yelled out, “We love you, Jenny,” as the lights came up; and Jenny yelled back, “I love you, too.” The spotlight on her face grew brighter, and the orchestra began to play. Jenny Bowman was home again, back where she belonged.”

THE END

(accessed via the official Dirk Bogarde website: http://dirkbogarde.co.uk/magazine/screen-stories-may-1963/)

Following Judy’s return to the stage David’s absence is not noted in the text. Neither is his presence – it almost seems as though he is irrelevant. Jenny’s need for love is fulfilled by her adoring audience and it is stated that she is ‘home again, back where she belonged’

This led us to briefly consider Bogarde’s off screen role. While Bogarde’s support is partially seen in his not competing with Garland for the emotional scenes, information he purportedly provided about the production gives further insight. He claimed that, sanctioned by Garland, he rewrote some of Jenny’s dialogue (John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2004, p. 287) This potentially gave Garland more agency, a matter about which the melodrama group had earlier expressed concerns. It also highlights Bogarde’s many talents – he had a successful career as a writer as well as an actor. Furthermore, in addition to reminding us of the importance of production and reception contexts, it highlights the fact that such contexts place stars among other stars, both on and off the screen.

This led us to briefly consider Bogarde’s off screen role. While Bogarde’s support is partially seen in his not competing with Garland for the emotional scenes, information he purportedly provided about the production gives further insight. He claimed that, sanctioned by Garland, he rewrote some of Jenny’s dialogue (John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 2004, p. 287) This potentially gave Garland more agency, a matter about which the melodrama group had earlier expressed concerns. It also highlights Bogarde’s many talents – he had a successful career as a writer as well as an actor. Furthermore, in addition to reminding us of the importance of production and reception contexts, it highlights the fact that such contexts place stars among other stars, both on and off the screen.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk and let me know you’d like me to add your thoughts to the blog.