We were very pleased to recently welcome back writer/director Tamsin Flower, about 6 weeks after her last visit. It was great to read the first draft of her play TRANSFORMER in full, after the excerpts we were treated to last time. This was especially useful due to the play’s complex and thought-provoking structure. The play’s main characters, overbearing mother Norma and the far less sure of herself and still-developing Eddie, each has a different relationship to the films referenced.

We particularly commented on the impactful nature of the first two scenes. In the first, Eddie’s tangle with an impresario comments on Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky) with her success in winning the dual role in Swan Lake prompting Norma to celebrate and reminisce about her own related experience. This second scene also involves an impresario, though Norma is far more knowing, and pushy, than the heroine she references: that of the young female ballet dancer Vicky (Moira Shearer) in The Red Shoes (1948, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger). The fact that the both the obsessive female dancer and the figure of the impresario are archetypes – as demonstrated by the act The Red Shoes is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s disturbing fairy tale (1845) – aids the audience’s recognition of both figures even if they are unfamiliar with the films. But the play delves far deeper than this as Norma and Eddie’s relationship to these related but diverging film texts, and of course to each other, are multi-layered.

We particularly commented on the impactful nature of the first two scenes. In the first, Eddie’s tangle with an impresario comments on Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky) with her success in winning the dual role in Swan Lake prompting Norma to celebrate and reminisce about her own related experience. This second scene also involves an impresario, though Norma is far more knowing, and pushy, than the heroine she references: that of the young female ballet dancer Vicky (Moira Shearer) in The Red Shoes (1948, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressberger). The fact that the both the obsessive female dancer and the figure of the impresario are archetypes – as demonstrated by the act The Red Shoes is based on Hans Christian Andersen’s disturbing fairy tale (1845) – aids the audience’s recognition of both figures even if they are unfamiliar with the films. But the play delves far deeper than this as Norma and Eddie’s relationship to these related but diverging film texts, and of course to each other, are multi-layered.

While both The Red Shoes and Black Swan focus on a woman’s love/hate relationship with dancing and the control it exerts on her, these women and the contexts of the films are very different. In The Red Shoes the ballerina literally cannot escape her compulsion, dancing up until almost her last moment when she jumps in front of a moving train. In Andersen’s story this a punishment for the pleasure she takes in her beautiful new red slippers she insists on wearing to church, with her only stopping once her slipper-encased feet have gruesomely been chopped off. The more modern Black Swan couches Nina Sayers’ (Natalie Portman) breakdown as the pressure between the oppositional good and bad characters she plays on stage, with the moral judgment of women seen in Andersen’s fairy tale replaced by recognition of the pressures women are under.

While both The Red Shoes and Black Swan focus on a woman’s love/hate relationship with dancing and the control it exerts on her, these women and the contexts of the films are very different. In The Red Shoes the ballerina literally cannot escape her compulsion, dancing up until almost her last moment when she jumps in front of a moving train. In Andersen’s story this a punishment for the pleasure she takes in her beautiful new red slippers she insists on wearing to church, with her only stopping once her slipper-encased feet have gruesomely been chopped off. The more modern Black Swan couches Nina Sayers’ (Natalie Portman) breakdown as the pressure between the oppositional good and bad characters she plays on stage, with the moral judgment of women seen in Andersen’s fairy tale replaced by recognition of the pressures women are under.

(For more on Black Swan see this earlier blog post: http://blogs.kent.ac.uk/melodramaresearchgroup/2014/03/08/summary-of-discussion-on-black-swan/).

Norma and Eddie’s relationship is commented on by the tension existing between both characters and the film texts they are connected to. This is seen as despite the fact Norma, as befitting her age, is linked to The Red Shoes, and Eddie to Black Swan, it is in fact the older Norma who pushes boundaries. In her retelling of her meeting with an impresario, asides convey her calculated behaviour. This is similarly demonstrated as she is present in part of Eddie’s first scene, taking over to tell her story and also commenting on the complex mother/daughter relationship present in Black Swan.

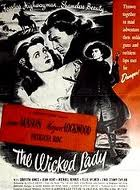

While Norma changes little, Eddie develops, after a crisis of identity leads to a period of estrangement and meaning that Eddie following her own path. Here the recognisable film tropes of women empowering themselves through education (Erin Brockovich, 2000, Steven Soderbergh) and of films’ makeover scenes (Clueless, 1995, Amy Heckerling) shine a light on the way audiences in general respond to stars, including as an ego ideal inspiring self-development. Norma is also ‘made-over’ (references to the classic Now Voyager, 1942, Irving Rapper) but her empowerment comes through her manipulation of men (The Damned Don’t Cry, 1950, Vincent Sherman). Even for modern day theatre audiences who might not be familiar with these specific (though widely available and mostly Hollywood) film texts, the fact they reference themes disseminated in films and indeed these themselves reflect their presence in other art forms/discourses of entertainment widens their appeal, reach and relevance. The script sets up the matter of how specific (though imaginary) audience members might appropriate material from well-known films with female stars whose characters undergo some sort of transformation. Furthermore, as film academics, many of us historians, this bridges the gap between historical audiences who can seem difficult to grasp, offering some insights into how texts are read, re-read and re-purposed including as part of people’ life narratives.

While Norma changes little, Eddie develops, after a crisis of identity leads to a period of estrangement and meaning that Eddie following her own path. Here the recognisable film tropes of women empowering themselves through education (Erin Brockovich, 2000, Steven Soderbergh) and of films’ makeover scenes (Clueless, 1995, Amy Heckerling) shine a light on the way audiences in general respond to stars, including as an ego ideal inspiring self-development. Norma is also ‘made-over’ (references to the classic Now Voyager, 1942, Irving Rapper) but her empowerment comes through her manipulation of men (The Damned Don’t Cry, 1950, Vincent Sherman). Even for modern day theatre audiences who might not be familiar with these specific (though widely available and mostly Hollywood) film texts, the fact they reference themes disseminated in films and indeed these themselves reflect their presence in other art forms/discourses of entertainment widens their appeal, reach and relevance. The script sets up the matter of how specific (though imaginary) audience members might appropriate material from well-known films with female stars whose characters undergo some sort of transformation. Furthermore, as film academics, many of us historians, this bridges the gap between historical audiences who can seem difficult to grasp, offering some insights into how texts are read, re-read and re-purposed including as part of people’ life narratives.

A particularly enjoyable and fruitful discussion revolved around the matter of pre-code films. This too relates to the matter of historically situated audiences as many today would be unaware that some films before the implementation of this heavier censorship in Hollywood (the Production or Hays Code in 1934) actually referenced matters like prostitution, child abuse and other weighty issues. We specifically discussed the pre-code Baby Face (1933, Alfred E. Green) – a film credited as partly responsible for more censorship being necessary. In this, Lily (Barbara Stanwyck) is a young woman who after years of abuse, including being prostituted by her own father, is encouraged (ironically enough by a man) to use men the way men have always used her – to employ sex for her own ends. Although Lily is in some ways ‘normalised’ – although she cold-heartedly climbs the ladder of executives at the company she is employed by she eventually marries her boss and realising her love for him she later sacrifices her hard-won jewellery – she still gains through using her sexual powers, although she may of course be given special justification due to the awful abuse she has suffered.

A particularly enjoyable and fruitful discussion revolved around the matter of pre-code films. This too relates to the matter of historically situated audiences as many today would be unaware that some films before the implementation of this heavier censorship in Hollywood (the Production or Hays Code in 1934) actually referenced matters like prostitution, child abuse and other weighty issues. We specifically discussed the pre-code Baby Face (1933, Alfred E. Green) – a film credited as partly responsible for more censorship being necessary. In this, Lily (Barbara Stanwyck) is a young woman who after years of abuse, including being prostituted by her own father, is encouraged (ironically enough by a man) to use men the way men have always used her – to employ sex for her own ends. Although Lily is in some ways ‘normalised’ – although she cold-heartedly climbs the ladder of executives at the company she is employed by she eventually marries her boss and realising her love for him she later sacrifices her hard-won jewellery – she still gains through using her sexual powers, although she may of course be given special justification due to the awful abuse she has suffered.

We contrasted this to The Damned Don’t Cry which is referenced in the play as Norma regales Eddie, and us, with how she used men to further her own financial standing. The Damned Don’t Cry is a somewhat uneven film, veering from severe sympathy for Edith Whitehead/Lorna Hansen Forbes (Joan Crawford) after the loss of her child and perhaps some delight in her turning the tables on men, though she does not have such a damaged background as Lily in Baby Face. Furthermore in the post-code and more conservative early 1950s Ethel/Lorna is punished by the killing of the man she loves by the one she has betrayed.

We contrasted this to The Damned Don’t Cry which is referenced in the play as Norma regales Eddie, and us, with how she used men to further her own financial standing. The Damned Don’t Cry is a somewhat uneven film, veering from severe sympathy for Edith Whitehead/Lorna Hansen Forbes (Joan Crawford) after the loss of her child and perhaps some delight in her turning the tables on men, though she does not have such a damaged background as Lily in Baby Face. Furthermore in the post-code and more conservative early 1950s Ethel/Lorna is punished by the killing of the man she loves by the one she has betrayed.

We also commented on the variety of genres referenced – Norma’s melodrama to Eddie’s drama, adaptation, romantic comedy, and horror. This too makes it more recognisable to various audiences and widens the appeal of the piece. In addition, we thought that the humour derived from Norma’s high campery (itself also chiming well with some of the film heroines she references) provided lighter and enjoyable moments.

We look forward to seeing the next draft of Tamsin’s script (thanks so much for sharing, Tamsin!) and to seeing it staged.

As ever, do log in to comment, or email me on sp458@kent.ac.uk to add your thoughts.