2016 gropes blindly forward, bludgeoning its way through each month at the expense of more well-loved musicians; first there was Bowie, then Boulez; guitarist and co-founder of The Eagles, Glenn Fry; prog-rock’s Keith Emerson; and hot on the heels of the death of the incomparable comedienne and pianist, Victoria Wood, comes the news of the death of Prince at the age of fifty-seven.

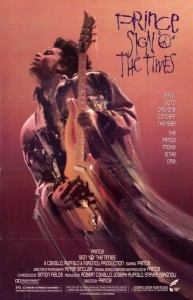

For those of my generation, Prince’s fierce creativity during the 80s was the backdrop to our formative years; cassette copies of Sign O’ the Times and Under the Cherry Moon exchanging hands feverishly, eager ears desperate to catch up with the latest release from the endless outpouring of creativity from the Prince stables. We air-guitared to the screaming agony of Purple Rain, or stepped light-footedly to Kiss and Alphabet Street. That famous SOTT poster, in which Prince squeezed his guitar orgasmically, adorned our bedroom walls. We were in thrall to this relentless fount of arresting, driven music, created by this pint-sized genius who swaggered around on the stage in platform heels and outrageous outfits, the epitome of pop’s immediate, glamorous appeal and yet somehow also impossibly cool at the same time. If you didn’t know the latest Prince song, or hadn’t got a copy of the new album, you weren’t worth talking to. He seemed to flirt with you too, whether you were a boy or a girl, the taunting ambiguity of If I Was Your Girlfriend, or the come-hither knowing look which promised, lured and generally batted its eyelashes at you from the cover of Lovesexy. He exhibited such a confident sexuality, a surety in himself that gave his provocative lyrics and stage-strut such power, that was awe-inspiring to my gawky, angst-ridden teenage self. “If I gave you diamonds and pearls,’ he sang, ‘would you be a happy boy or a girl ?’ I still recall idly channel-hopping and stumbling across Channel 4’s broadcast of the Sign o’ the Times film (with Eric Leeds playing sax in what seemed to be a hooded monk’s robe); I’d never seen anything like it before, so blatantly theatrical yet so musically vibrant and flawlessly executed, it was astonishing.

For those of my generation, Prince’s fierce creativity during the 80s was the backdrop to our formative years; cassette copies of Sign O’ the Times and Under the Cherry Moon exchanging hands feverishly, eager ears desperate to catch up with the latest release from the endless outpouring of creativity from the Prince stables. We air-guitared to the screaming agony of Purple Rain, or stepped light-footedly to Kiss and Alphabet Street. That famous SOTT poster, in which Prince squeezed his guitar orgasmically, adorned our bedroom walls. We were in thrall to this relentless fount of arresting, driven music, created by this pint-sized genius who swaggered around on the stage in platform heels and outrageous outfits, the epitome of pop’s immediate, glamorous appeal and yet somehow also impossibly cool at the same time. If you didn’t know the latest Prince song, or hadn’t got a copy of the new album, you weren’t worth talking to. He seemed to flirt with you too, whether you were a boy or a girl, the taunting ambiguity of If I Was Your Girlfriend, or the come-hither knowing look which promised, lured and generally batted its eyelashes at you from the cover of Lovesexy. He exhibited such a confident sexuality, a surety in himself that gave his provocative lyrics and stage-strut such power, that was awe-inspiring to my gawky, angst-ridden teenage self. “If I gave you diamonds and pearls,’ he sang, ‘would you be a happy boy or a girl ?’ I still recall idly channel-hopping and stumbling across Channel 4’s broadcast of the Sign o’ the Times film (with Eric Leeds playing sax in what seemed to be a hooded monk’s robe); I’d never seen anything like it before, so blatantly theatrical yet so musically vibrant and flawlessly executed, it was astonishing.

There were the dark years, in which he wrangled with Warner Brothers over creative decisions and speed of album releases; there were stories about huge bins of recorded takes, whole swathes of music that the record label wasn’t putting out because it couldn’t keep up with him and was stifling his apparently limitless creativity; the name changed, interviews were denied, he refused to speak and wore a handkerchief over his face, ‘slave’ tattooed on his cheek; there were some fallow albums – who remembers the sprawling Emancipation ? and Diamonds and Pearls is highly forgettable – but 2004’s Musicology was a return to the Prince of old, and he was always one step ahead of the game, evident in his releasing later albums as cover-mounts on tabloid newspapers, believing that albums were a signal for live performance and the shows. And that, reportedly, is where his genius lay, the legendary after-show jam sessions that would run for hours and had greater kudos than the live gigs, the stage performances full of energy and drive and flamboyant costumes. The film Purple Rain was mainly soft-focus soft porn, but it spawned a soundtrack that transcended the comparative poverty of its film to become one of the greatest pop albums of all time. There was a sense, too, that even his cutting-room floor leavings were better than what others mainstream artists were releasing.

Unlike his main rival to the title of Prince of Pop, Michael Jackson, you never felt that Prince had gone off the rails or lost touch with the business of making music, never mind the endless creativity. His million-dollar Paisley Park studio never bloated into the ill-conceived Neverland that became an emblem of Jacko’s lost grasp of reality. Prince was always about the music, the white-heat of recording and performing that governed his career. Rhythm and blues, in the older sense of the term, remained at the heart of Prince’s output, but he brought to it an inventiveness that gave it renewed swagger; just listen to the closing chords of the full version of Purple Rain, those aching harmonies yearning over a circling piano-figure, slowly shifting colours at the exhausted finale of one of the greatest pop ballads ever written.

But he could be funky too: funky as hell. Think of Sexy MF, New Position or Controversy.

Or Kiss, covered immortally by the great Tom Jones;

the euphemistic Tambourine from Around the World in a Day; and the unstoppable, barrelling energy of Life Could Be So Nice. He flirted with jazz, too, being the multi-tracked performer on the various number-titled albums with Madhouse and saxophonist Eric Leeds, as a side-project. Because, damn him, he was a poly-instrumentalist who played everything on early albums like For You, and sang too. It was ridiculous, really. And he could write such intimate, heart-breaking songs like Sometimes it Snows in April, that could pull you up short and wrench at your heartstrings. Sinead O’Connor’s greatest moment in the pop limelight, Nothing Compares 2 U, was penned by Prince.

For me, three minor gems sum up his musical magic: from 20Ten, the nimble funk of Sticky Like Glue and the dreamy ballad Walk in Sand, the polar opposites of what he did best, and from 2014’s Art Official Age, the understated, hip-shimmying Breakfast Can Wait.

Here, in the realm of us mortals, the doves may be crying, but you can be sure that upstairs, there’s now one heck of a gig going on: Miles Davis, Prince and Bowie. It seems fitting, for someone whose music seems to have come from another planet, to let those final chords of Purple Rain circle and lift as he goes back. The world mourns the loss of one of its brightest, most creative musicians, who will remain, always, indisputably, the Prince of pop.