Jazz may be all about the elasticity of time, about syncopation and the louche indolence of swing, but, to paraphrase George Gershwin, it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got a regular pulse. (I can see why Ira changed the lyrics…)

You can’t pull against something if it’s not firmly fixed: in jazz, that’s the hi-hat. The crisp snap of the hi-hat on the second and fourth beat of a swing tune in 4/4 represents the twin pillars of the piece’s rhythm, around which swing can loll and flounce, secure in the knowledge that it is underpinned by a rock-solid rhythmic foundation. Music is often about the suspension of time, or what the American composer Elliot Carter has called the debate between ‘chronometric time versus psychological time,’ the regular pulse of the daily passage of life pitted against a time-scale imposed by the piece of music itself. Time, in jazz, slips and slides like a novice ice-skater, but one clinging firmly to the hoarding lining the rink: the security of the drum-kit.

Listen to the opening of Milestones, where the crisp homophony of the sideways triadic motion in the saxes and trumpet only works because the percussion defines exactly where the beats against which they are pulling lie: the driving ride cymbal and crisp rim-shot anchoring the beats.

And Dave Brubeck’s Take Five succeeds because the bass player roots the pulse firmly on the tonic ‘E’ every time the five-beat cycle begins anew, along with the pianist’s left-hand and a solid kick on the bass-drum.

(And, as an extra bonus, I love the descisive thwack on the snare(less) drum that marks the beginning of Desmond’s alto-sax solo when the tune ends in this clip).

The writer Michael Hall’s epithet which titles this post is spot on: the hi-hat provides the necessary beat. Next time you’re playing in a jazz ensemble, or improvising a solo, or simply listening to some Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie, keep an ear out for the drummer: he’s holding it all together.

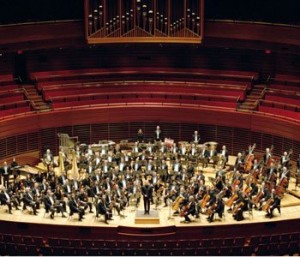

Is period-instrument reconstruction of Baroque and Classical music the new contemporary music ? And should performances by modern orchestras or pianists using contemporary pianos take period-practice into account ? Would Mozart and Beethoven have approved ?

Is period-instrument reconstruction of Baroque and Classical music the new contemporary music ? And should performances by modern orchestras or pianists using contemporary pianos take period-practice into account ? Would Mozart and Beethoven have approved ?