‘May you live in interesting times,’ runs the ancient saying. The second part, possibly lost in the mists of time since it was first uttered, may have been something along the lines of ‘and may you also have to adapt your working practices to cope with sudden, profound change.’ Maybe.

The current climate of self-isolation and social distancing is anathema to much of the creative arts, both to the way they are realised and the way they are consumed. Collaboration in both creating and experiencing – rehearsals, combined writing and working together, audiences in concert halls, visitors in art galleries – is suffering hugely in the present situation, and artists and audiences are finding new ways of working together, presenting together and listening and watching together. (Netflix Watch Party, anyone ?!) The phrase I’m most often hearing at the moment is people talking about ‘finding a way to make it work,’ a sentiment at once both urgent in its intent as well as hugely positive in what it reveals about the mindset of many at the moment – we’re all finding ways in which to make things carry on, to reconfigure our working practices to allow them to continue.

Watching the artistic world respond to governmental and scientific advice to stay at home is fascinating, seeing practitioners reinvent ways of continuing to work, driven by the two-fold need to still be working (for freelance artists, especially, the current climate is fearful) and also to be responding to the crisis artistically themselves, expressing their response in words, music, painting. Because that’s what the arts do: they reflect, respond to the zeitgeist, and they stand afterwards as testament to how humanity reacted. David Hockney responded last week by sharing his iPad paintings, created under lockdown at his home in Normandy, reacting to the prevailing gloom with vibrant colours capturing the return of spring – as human life currently stumbles and gropes its way forward, nature continues to blossom.

Watching the artistic world respond to governmental and scientific advice to stay at home is fascinating, seeing practitioners reinvent ways of continuing to work, driven by the two-fold need to still be working (for freelance artists, especially, the current climate is fearful) and also to be responding to the crisis artistically themselves, expressing their response in words, music, painting. Because that’s what the arts do: they reflect, respond to the zeitgeist, and they stand afterwards as testament to how humanity reacted. David Hockney responded last week by sharing his iPad paintings, created under lockdown at his home in Normandy, reacting to the prevailing gloom with vibrant colours capturing the return of spring – as human life currently stumbles and gropes its way forward, nature continues to blossom.

Institutions and organisations are also having to change their approach, with many capitalising on the digital possibilities by offering virtual tours and concerts streamed online. The Metropolitan Opera in New York is streaming a complete performance each day; listeners can enjoy a free trial of the Berlin Philharmonic’s virtual concert-hall; the Royal Opera House is offering free broadcasts on YouTube and Facebook; the BBC’s whole #CultureinQuarantine strand; these are instances of organisations both adapting to and embracing the new possibilities offered by reaching out to people and engaging audiences on digital platforms, stepping right into their homes.

For musicians, especially ensemble musicians such as choirs, orchestras and chamber groups, the ability to interact directly with other performers, to respond to their ways of shaping, to follow the act of breathing as singers or woodwind players prepare for a phrase or to watch the bowing-arm on a violinist as they prepare to play, is critical to the act of ensemble performing: we need the immediacy of working in close proximity to others to be able to participate in group music-making. The lagging and pacing required when interacting digitally through many of the various platforms – FaceTime, Zoom, Teams – deals these a virtual (in both senses of the term) death-blow to collective performing. And the same is true for teaching; watching my wife completely re-think and re-shape her singing lessons to be able to deliver them online to pupils who are notionally still at school has been a fascinating process; lessons need to be paced differently, aspects of teaching that would normally be done together now need to be undertaken differently, almost a digital call-and-response, to allow teacher and pupil to continue working together.

For the Music Department here at the University of Kent (I use the word ‘here’ in the context of working from home – we no longer need to take work home with us, it’s here with us all the time at the moment…!), finding new ways of working and performing together has been at the forefront of our thinking since the culture-shift began around three weeks ago. Key questions have emerged: how do we keep student, staff and community musicians engaged under the current conditions ? How can we keep people working together ? How do we boost morale ?

One of the ways in which we’re doing this is through the Virtual Music Project, which launched on Friday 27th March in order to create a virtual performance of Vivaldi’s Gloria, a masterwork of the Baroque era, which requires choral singers, soloists and instrumentalists. Gone are the ensemble rehearsals and the choir practices with which we would normally have put the performance together; instead, we’re encouraging musicians amongst the University community to get involved by downloading the music, learning and recording it at home, and submitting it – the idea is to bring all these separate recordings together, and combine them into a digital ensemble performance.

One of the ways in which we’re doing this is through the Virtual Music Project, which launched on Friday 27th March in order to create a virtual performance of Vivaldi’s Gloria, a masterwork of the Baroque era, which requires choral singers, soloists and instrumentalists. Gone are the ensemble rehearsals and the choir practices with which we would normally have put the performance together; instead, we’re encouraging musicians amongst the University community to get involved by downloading the music, learning and recording it at home, and submitting it – the idea is to bring all these separate recordings together, and combine them into a digital ensemble performance.

Whilst nothing can, of course, ever replace the immediacy and the energy of communal rehearsals, what this project does afford is the chance for people to use their time in self-isolation to continue learning, practicing and performing music, to maintain their skills and their levels of ability, and to feel they are still participating in a shared musical endeavour even whilst we are all shut up in our homes. And it’s that sense of working together as part of a combined artistic project, of being part of something alongside other musicians and performers, that is so sorely lacking in these times. The arts, and music especially, thrives on combined endeavour, on the thrill of accomplishment that comes in delivering a performance of which you were a part.

Whilst nothing can, of course, ever replace the immediacy and the energy of communal rehearsals, what this project does afford is the chance for people to use their time in self-isolation to continue learning, practicing and performing music, to maintain their skills and their levels of ability, and to feel they are still participating in a shared musical endeavour even whilst we are all shut up in our homes. And it’s that sense of working together as part of a combined artistic project, of being part of something alongside other musicians and performers, that is so sorely lacking in these times. The arts, and music especially, thrives on combined endeavour, on the thrill of accomplishment that comes in delivering a performance of which you were a part.

An important part of this endeavour is reaching out to engage people who might be feeling isolated or alone and vulnerable at this time. Many of us need a purpose, an order or a structure to our day in order not to feel cut off; practicing and playing music offers a valuable way of occupying the mind and the body at a time when we are being advised not to leave our homes and only to take exercise once a day. Those involved in the project have a purpose, something towards which to work, something in which they can continue to be involved.

An important part of this endeavour is reaching out to engage people who might be feeling isolated or alone and vulnerable at this time. Many of us need a purpose, an order or a structure to our day in order not to feel cut off; practicing and playing music offers a valuable way of occupying the mind and the body at a time when we are being advised not to leave our homes and only to take exercise once a day. Those involved in the project have a purpose, something towards which to work, something in which they can continue to be involved.

And it has mobilised some of the University’s alumni community as well; one of the loveliest things about the project has been seeing students from across the years getting in touch, making and sending in their recordings and mentioning how exciting it is for them to be involved in a musical project at Kent once more. There is an international aspect to the project, too; recordings and photos have arrived from participating musicians from Germany, Canada, France, and I’m currently waiting for one from Luxembourg. Music truly is a universal language; the project has clearly – and I hope you will forgive a gratuitous pun – struck a chord…

And it has mobilised some of the University’s alumni community as well; one of the loveliest things about the project has been seeing students from across the years getting in touch, making and sending in their recordings and mentioning how exciting it is for them to be involved in a musical project at Kent once more. There is an international aspect to the project, too; recordings and photos have arrived from participating musicians from Germany, Canada, France, and I’m currently waiting for one from Luxembourg. Music truly is a universal language; the project has clearly – and I hope you will forgive a gratuitous pun – struck a chord…

One distinctly novel aspect that the project has afforded is the opportunity for people to be involved in the performance in more than one way, something that would be physically impossible in the concert-hall. Floriane Peycelon (pictured above), a freelance musician and teacher based in Folkestone who directs the University String Sinfonia and teaches string-playing Music Scholarship students at Kent, has revealed herself as an unstoppable tour de force in recording not just the violin part, but the viola part and alto part too – in effect, appearing three times in the finished recording!

One distinctly novel aspect that the project has afforded is the opportunity for people to be involved in the performance in more than one way, something that would be physically impossible in the concert-hall. Floriane Peycelon (pictured above), a freelance musician and teacher based in Folkestone who directs the University String Sinfonia and teaches string-playing Music Scholarship students at Kent, has revealed herself as an unstoppable tour de force in recording not just the violin part, but the viola part and alto part too – in effect, appearing three times in the finished recording!

Capturing the visual element of the virtual project is important, too, the faces behind the sounds. It can be easy to lose sight of the individuals working to put the project together, giving of themselves in performing and rehearsing their part. You can see and watch musicians perform in the concert-hall, in pubs and clubs, on bandstands and on-stage – it’s important to reflect this aspect of the project too, human beings making the recordings and still putting time and energy into performing, even though it’s behind closed doors and invisible to everyone else; the dedicated Pinterest board reflects the human stories behind the developing project.

Capturing the visual element of the virtual project is important, too, the faces behind the sounds. It can be easy to lose sight of the individuals working to put the project together, giving of themselves in performing and rehearsing their part. You can see and watch musicians perform in the concert-hall, in pubs and clubs, on bandstands and on-stage – it’s important to reflect this aspect of the project too, human beings making the recordings and still putting time and energy into performing, even though it’s behind closed doors and invisible to everyone else; the dedicated Pinterest board reflects the human stories behind the developing project.

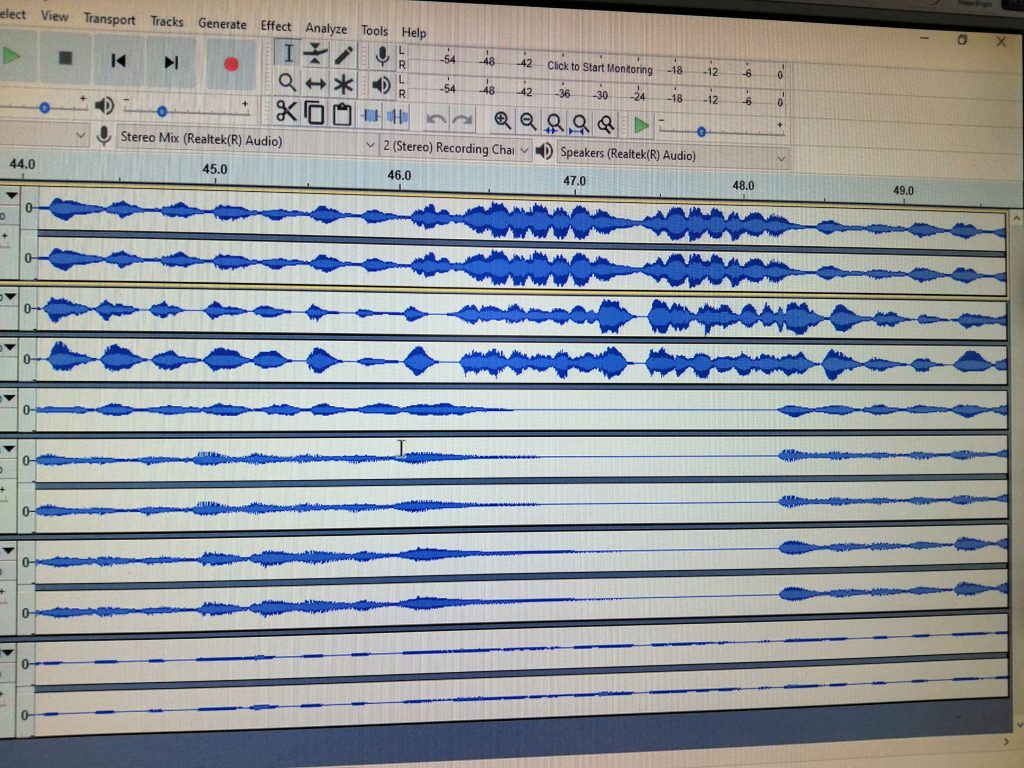

So, whilst it’s true that I currently spend more time at my workstation at home, running the project and starting to lace the recordings together, and less in the rehearsal room or Colyer-Fergusson Hall than usual, my time is still creative, still collaborative; I’m still working with others, sending out recordings of piano or harpsichord parts I’ve made to support people as they rehearse and record; piecing together the various recordings as they arrive in my inbox, starting to build the digital ensemble.

So, whilst it’s true that I currently spend more time at my workstation at home, running the project and starting to lace the recordings together, and less in the rehearsal room or Colyer-Fergusson Hall than usual, my time is still creative, still collaborative; I’m still working with others, sending out recordings of piano or harpsichord parts I’ve made to support people as they rehearse and record; piecing together the various recordings as they arrive in my inbox, starting to build the digital ensemble.

And there’s a Virtual Dance Orchestra too, currently putting together – and the irony is fully intentional – a virtual performance of Don’t Get Around Much Anymore. With the wealth of repertoire, particularly Baroque music, that is available, and the sets of dance orchestra parts I have put together, this project can run for as long as it needs to. Hopefully, it won’t be needed much longer – but I have plans to continue with the idea long after our doors open once more and we are able to step outside, to meet with others, to share our stories and our experiences, and return to working collaboratively, creatively, and – most important of all – together.