There is something almost unbearably melancholic about Satie’s elegaic song, ‘Je te veux,’ especially in this beautifully nuanced performance by Jessye Norman.

That initial gesture is the key to the whole piece – a yearning, a reaching for something (or someone), with the arch-shape of the melody going beyond the tonic and and moving over it. without staying on it for any significant length. The fact that the melodic line doesn’t dwell on the tonic gives the piece its rootless, moving quality. The only time we really feel at ease is at the end of the verse (and its subsequent reprises), when the line finally descends onto, and remains on, C, a fact Satie emphasises at the eventual end of the piece when the melody ends with those final three descending notes (E to C) transposed up an octave.

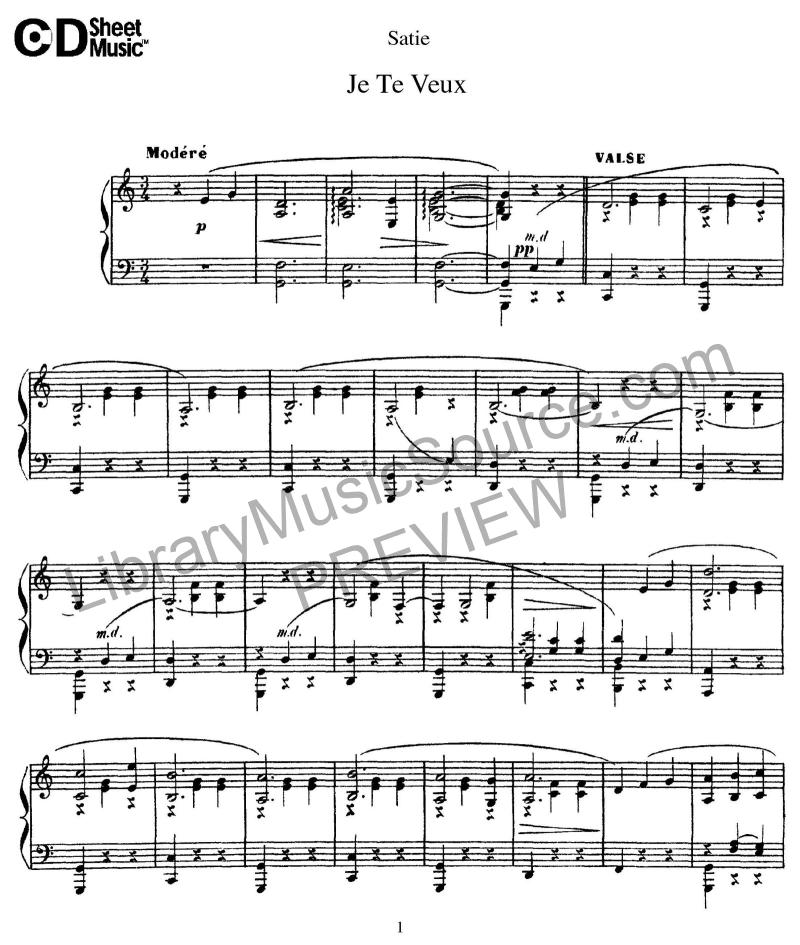

(You can see a copy of the score for solo piano here.)

Satie published it in several incarnations – piano and voice (1903), orchestra, brass and piano solo. For all his riotous tricks in the later ballet scores Parade and Relache, the quirky titles and in-score annotations for the performer to read in piano works such as the Sonatine bureacratique, Je te veux is perhaps a rare moment of Satie wearing his heart on his sleeve. It’s a short, lyrical, and somehow achingly sad moment amongst the rest of Satie’s challenging output.