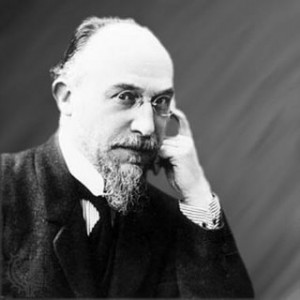

United across centuries: weird composer Erik Satie and Brit pop group Take That. Surely not ?

United across centuries: weird composer Erik Satie and Brit pop group Take That. Surely not ?

But yes. In Satie’s ballet-realiste Parade from 1917, three Actor-Managers set up a side-show outside their tent, in an effort to attract an audience to see their show. Sadly, their efforts prove in vain: the spectacle outside the tent becomes the main attraction, and no-one is enticed in to see the proper performance inside.

You can hear this sense of desperate futility in the episode of the Chinese Magician, where the jollity of the music and the whistling in the percussion are overwhelmed by ponderous orchestration and repetition leading nowhere. At the end of the piece, exhausted by their futile efforts, the characters slump to the ground in defeat.

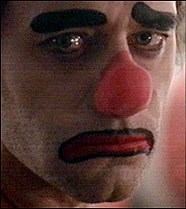

This sense of desperation is also captured to great effect in the video to Take That’s Said It All, released in 2009, where all the energy and antics of the clowns cannot move the audience, because the tent is empty. There’s no-one there to appreciate their manic efforts: as with the Satie, the main focus of the show, the audience, is absent, and the characters can only act out their performances with a sense of forlorn hope.

This sense of desperation is also captured to great effect in the video to Take That’s Said It All, released in 2009, where all the energy and antics of the clowns cannot move the audience, because the tent is empty. There’s no-one there to appreciate their manic efforts: as with the Satie, the main focus of the show, the audience, is absent, and the characters can only act out their performances with a sense of forlorn hope.

Shot in muted and washed-out colours, thereby depriving them even of the imposed jollity of their colourful outfits, there are some beautiful sequences; there’s a sense of resignation about them as they dress for what they know will be a pointless show. Clowns are rescued from the ludicrous nature of their garb and their slapstick antics through audience laughter, redeemed through the mirth they create for others. There’s none of that here: no redemption for them at all.

(You can see the actual video to the piece here.)

In both works, futility is elevated to the status of art, and circus characters, whose very existence is to entertain, end up deprived of their ability to do so. The same sentiment expressed over a distance of over ninety years in two very different cultures.

Satie and Take That ? Absolutely.