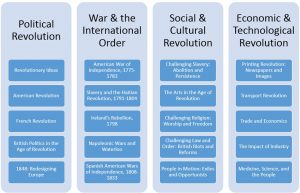

In the past two months, I’ve been attempting the impossible: to summarise the most significant things that happened during the Age of Revolution, and to explain and justify why these things were important and how they connected to one another.

Age of Revolution Theme Summaries & Key Messages BJM

It’s been quite a writing challenge – we’re habituated to having quite a lot of control over our subject area, or speaking internally to one another about research sub-fields, and to concentrate on archival finds and quite detailed debates and issues in one place, time, or theme. It’s also required a bit of courage – every generalisation in large sweeps of history is so vulnerable to objections, caveats, corrections, and critique. And inevitably, so much of this stuff is – to use the perennial escape line for historians – “not my field.” But there are good reasons for grappling with the macro, and chewing cud in other people’s fields, as well as having to be selective. These cut to the core of what history is, or should be, about. Fundamentally, if the history we produce is not usable and purposeful – if it cannot be articulated and understood, and made relevant to people and classrooms today – then the enterprise risks not only losing popular and state support, but also leaving the big picture painting to those who haven’t necessarily trained in the discipline.

Thankfully, colleagues within the Age of Revolution team have ridden to my rescue, so thanks to them for the many inflections and tweaks this has gone through. I now submit it, as the Declaration of Independence put it, to the “Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions.” And feel free to comment on it, correct it, and chew it over. Hopefully some of it will be useful as the various teams in the project think more deeply and fully about many of the historical themes and developments, and how we can explain and vivify them in museums and classrooms.