Link to survey: https://poll.fm/10344546.

If you had to pick thirty historical figures whose lives and legacies collectively represented the Age of Revolution in c.1775-1848, then who would make the cut? Thirty seems a large number at first. But given the international scale and social reach of the revolutionary changes in the period, when – as Thomas Paine put it in the final words of his first volume of Rights of Man, “nothing of reform in the political world ought to be held improbable…everything may be looked for,” – it quickly becomes an interesting and a thorny challenge.

The question is more than just a hypothetical one for us at the UK’s educational project, Age of Revolution: Making the World Over (https://ageofrevolution.org/), because we are working with a company to design a new card game. The Age of Revolution project is funded by a charitable trust, originally set up (with UK government support) for the commemoration of the bicentennial of the Battle of Waterloo in 2015. The legacy funding since 2017 has been directed to provide new resources and activities for schools in a number of innovative ways, in order to support teaching and learning about the period’s history. It therefore offers a great chance to think creatively and to try to bring the latest research and scholarship into view, in such a way as will engage younger people (from age five upwards) and draw them to the history of the period.

The period 1775-1848 tends to lose out in many corners of the increasingly pressurised British school educational system, in the face of more popular or well-established study units (departments typically pick World War 2 or the sixteenth-century Tudors for their curriculum, for instance). The Age of Revolution’s lack of a clear metanarrative, its complexity, and its diverse geography mean it is a challenge to fit in, especially at younger ages. The hooks that once gripped it are increasingly rusty in an educational setting that rightly rejects imperial myths and Whig narratives. But these myths and narratives are thriving in popular culture – very much a part of what has fuelled the Brexit agenda – so we need to find new ways to bring the period to attention, explain its relevance, and bring it to life. In the project so far, we have concentrated on developing a suite of digitized objects from the Age of Revolution, in partnership with museums and archives, and scaffolding these images with explanatory text, teaching ideas, and with audio podcasts. We’re shortly to make available online a free schools’ edition of a new graphic novel about the Peterloo Massacre (an episode of mass protest in Manchester in 1819 that was savagely repressed by British local and state authorities), that offers a fresh way visualising and contemplating protest, and putting children at the centre.

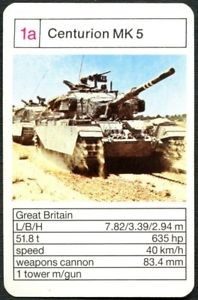

So why the need to choose thirty figures? “Top Trumps” playing card sets (first launched commercially in 1978) were originally the province of geeky and historically masculinised topics – cars, tanks, fighter jets and so on – which lent themselves to numerically comparative data and schoolground competition. Since being relaunched in 1999, the topics have broadened to encompass card sets of thirty cards featuring the natural world (predators and dinosaurs do well), sporting celebrities, and characters in cult movie franchises. Now, in today’s distracted world of Iphones and other hand-held electronic devices, an old-fashioned card game may seem very retro, but “Top Trumps” can and have been used to great effect in the classroom. The format is simple: each card has a set of numerical values across four of five categories. You have to play with whatever card is next in your hand. And when the first player calls a category, whoever has the highest value wins the cards that round. So let us imagine Mary Wollstonecraft is pitted against George Washington, and the category is “Combat Power,” then one would expect Washington to win hands down. But had the category been “Radicalism,” (we might imagine her card value to trump his, with hers at, say, 93% and his 27%) then the boot would have been on the other foot.

The surface benefits of “Top Trumps” as a pedagogical tool for children aged 7-15 are that they introduce a competitive edge and focus, they encourage comparative framing, and they support knowledge recall. Play with a pack for long enough, and you won’t know why, but you will remember that a Great Hammerhead Shark can swim to a depth of 80 metres. Their value increases though, because they prescribe ways of connecting individual subjects and – when broken down into additional research or learning exercises, or creative activities – they allow us to consider questions of selection and value. What is “combat power” and why does Mary Wollstonecraft’s card not have it listed very highly? Wasn’t George Washington a radical figure? Or wasn’t he more radical than he is being credited for here? On what grounds should he have been assigned a quantitative value of 54% instead of the arbitrary 27% I just gave him? Whether it is a question of finding out about the historical lives and context of the protagonists, breaking down the questions inherent in the categories, or breaking down the purported numbers, the framing of “Top Trumps” can therefore offer just as much insight and enjoyment as the gaming.

We want to create this set of thirty figures (and in due course, print and circulate them to hundreds of schools in the UK and perhaps beyond) in the spirit of the Paine quote listed above – including its emphasis that “everything may be looked for.” It is therefore important that we capture thirty figures in this small net whose lives, impact, and experiences were diverse. We are looking for a balance of people of mixed geography, race, and gender who sought in their own ways to “make the world over” and who exerted influence over the events and ideas of their era. The need to include these diverse voices and faces will add, of course, to the dilemma of excluding big traditional names – though this has the dual benefit of bringing the exercise into step with recent situational and corrective scholarship in the field. The aim is to end up with a cast list, whose individual lives we can project onto card form, as a short textual summary, with an image, alongside the playful statistics (which will likely include categories such as “Legacy” and “Glorious Death”). Put together, it’s hoped that these cards will convey a sense of the drama, diversity, and the stakes at large in the Age of Revolution.

We have until the end of July to lock these names down, and we would welcome your help and views. There are currently 52 suggested names (as it happens, a normal playing card pack) listed at our survey: https://poll.fm/10344546. All you need to do is vote for those who you feel definitely belong in contention. We can then take stock on 31 July of which historical figures most resonate and warrant inclusion.

You are most welcome to propose and vote for other contenders, and to enlarge the list. They need to be real people, not mythical or emblematic, and they need to have a connection to the battles for political and social change in Britain, Europe, the Americas, or the wider world between 1775 and 1848. There is scope to leave comments and ideas, and we’ll let you know here who makes the final cut in due course.

Thanks for taking time to take part!