by Annie Sharples

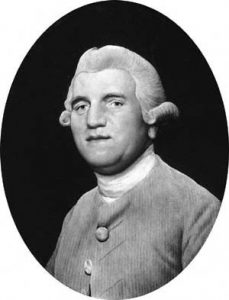

Josiah Wedgwood was an English potter and business man who is credited with the industrialisation of the production of pottery as well as inventing modern marketing. Wedgwood was born in 1730 and was a Unitarian and prominent abolitionist, becoming a key member of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. His main contribution to the abolitionist cause was producing the first anti-slavery medallion in 1787, depicting a kneeling slave in chains, with the phrase “Am I Not a Man and a Brother”. These medallions were mass produced and distributed and became widely worn and acknowledged, bringing public attention to the abolitionist movement. Wedgwood and the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was so revolutionary in the context of eighteenth-century society, as slavery was widely accepted and relied upon, particularly economically, as much of wealthy British society was built using the profit from the slave trade. Thus, opposing slavery was opposing many wealthy and powerful members and groups of society.

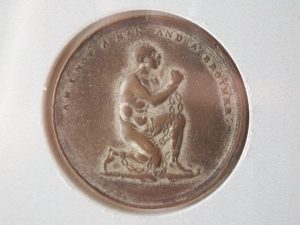

Many of these medallions can be seen in museums and in use; this particular one belongs to the New Room in Bristol, which was founded in 1739 by John Wesley, making it the oldest Methodist building in the world. Wesley was the founder of Methodism and, like Wedgwood, was committed to the abolitionist cause and preached against slavery as well as writing a pamphlet titled ‘Thoughts Upon Slavery’, published in 1774 and widely circulated and read, in which he stated ‘I strike at the root of this complicated villany; I absolutely deny all slave-holding to be consistent with any degree of natural justice’.[1] Wesley was a very influential figure in the fight against slavery, and his last piece of writing was a letter to William Wilberforce from his deathbed urging him to continue his work for abolition and assuring him that God was with him. Wedgwood admired Wesley and is said to have presented him with a special teapot, that was then subsequently mass produced. In the nineteenth-century Wedgwood’s pottery company also produced much of the Wesleyana, which is a collection of carved and moulded effigies celebrating the life and work of John Wesley, made from a variety of materials but the majority being ceramic.[2]

The medallion was actually designed by William Hackwood, who worked closely with Wedgwood, and it became the most famous image of a black person in all of eighteenth-century art.[3] The image and phrase became well known and a well-used and recognised symbol of allegiance to the abolitionist cause. Many people found original and creative ways to don these medallions. Thomas Clarkson, a leading abolitionist, describes in his 1808 memoirs that men ‘inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuffboxes. Of the ladies several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for the hair. At length, the taste for wearing them became general; and thus fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity, and freedom’.[4]It is unknown as to how many medallions were made and distributed as well as how many variants of it there were, though it is clear that a great number were produced.[5] The medallion is still used today as a symbol and is often reproduced and used when commemorating the Abolition Act of 1807. Thomas Clarkson credited Wedgwood’s medallions with being instrumental in ‘turning the attention of our countrymen to the case of the injured Africans, and of procuring a warm interest in their favour.’[6]

It was not only visual material, like Wedgwood’s medallion, that stirred abolitionist sentiment into fashionable society. Poetry was often a very popular and effective in communicating the abolitionist cause; poets including Hannah More, who was born in Bristol and lived there at the same time as Wesley did and both John and Charles Wesley were friendly with Hannah’s sister Mary.[7] More’s poem Slavery was published in 1788 and she was involved in a prominent group of abolitionists, including Wilberforce, and was known for encouraging women to join the anti-slavery movement. Another well-known abolitionist poet was William Cowper, whose 1788 poem The Negroes Complaint became famous and was often quoted during the civil rights movement in the United States centuries later by Martin Luther King Jr. Singing was also very popular amongst slaves, as a way of communicating with one another as well as expressing feeling. Songs were often passed down through generations.

The image of the kneeling slave, despite Wedgwood clearly advocating abolition, could potentially be problematic. Depicting the slave kneeling accurately demonstrates the huge imbalance of power, as it puts the slave in the weaker position; the slave is shown to be humbly asking for compassion, posing no threat. However, presenting the slave in this manner, as passive and weak, it ignores the resistance and revolutions that were initiated by enslaved communities, wiping important stories from history. One example of an influential slave rebellion is the Andry’s Rebellion, also known as the German Coast Uprising, which took place in January of 1811 in the Territory of Louisiana. This is the largest slave revolt in the history of the United States, and between 200 and 500 slaves marched on the German Coast in the direction of New Orleans. Furthermore, Wedgwood’s medallion does not portray the atrocious brutality of slavery and the horrific mental and physical anguish slaves suffered. All of this puts the focus on the slave begging for freedom, rather than the atrocities committed by the slave owners and slave traders. On one hand, it should be the enslaved people that are the focus of abolitionism, as they were greatly wronged and are so often written out of history by those with more power. Yet, on the other hand, the inhumane barbaric treatment towards slaves by slave owners and traders must not be allowed to be forgotten. In an article on the history.ac.uk website, the author argues that ‘To depict the enslaved African as begging for their freedom, pleading for the kindness and generosity of others so that they might be set free from bondage, is considered at best to be unhelpful and at worst continuing the very prejudice and discrimination which enslavement installed.’[8] The article goes on to argue that this image ‘ensures that its audience does not bear witness to the experiences of the enslaved but to the work of those who campaigned for an ending of the Atlantic slave trade. As a symbol, though the body of the enslaved is depicted, the actual corporeal experience of the enslaved is absent; the pain and horror of enslavement is not evidenced by the image.’[9] Mary Guyatt states that the slave’s confused depiction was a reflection of the conflicting demands the medallion had to meet, namely, the need to communicate its subject speedily and positively, whilst simultaneously gaining the viewer’s sympathy and arousing his or her admiration’.[10] These issues highlight the continuing need for this topic to be discussed widely and thoughtfully, yet despite this, Wedgwood’s medallion was a greatly significant contribution to the abolition cause.

Wedgwood’s medallion can be described as revolutionary as it is clearly promoting the abolition movement and widely spread an image of a black slave at a time when the black community was viewed as extremely inferior, and this view was generally accepted. As well as the medallion itself being revolutionary, the way in which it was used made it even more so, as it became an important symbol of revolution against slavery. Furthermore, the words “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” challenges the reader by suggesting that slaves should be regarded as fellow men, going further still with claiming to be a brother. By phrasing it as a question, the medallion challenges the reader, thus those who wore the medallion were challenging others to think. Guyatt argues that the slave in the image ‘shares characteristics with his audience in that he is clearly a Westernized figure: as well as speaking their language, the words he utters are themselves strangely reminiscent of the language of scripture’.[11] This highlights the immorality of slavery, both by claiming that all men are brothers as well as using religious language.

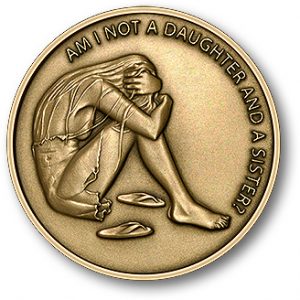

Others have used Wedgwood’s original medallion, such as the American writer Elizabeth Margaret Chandler, who was the first female American writer to make the abolition of slavery her primary theme. Chandler produced a very famous image, based on Wedgwood’s 1787 medallion, depicting a female slave kneeling and in chains with the words “Am I Not a Daughter and a Sister?” Much more recently, Ken King produced another anti-slavery medallion in 2010, again based on Wedgwood’s original design, but instead depicting a contemporary woman wearing ripped clothes with her head in her knees. On the other side of King’s medallion is a quote from the book of Proverbs, chapter 31, “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute. Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy.” King’s medallion focuses on sex slaves, tackling modern human trafficking and showing that despite slavery being illegal in the United Kingdom since 1807 and in the United States since 1865, it is still a huge issue.

Overall, this medallion is not only hugely significant and impressive in itself, but also in the way that is was so widely distributed and used as a symbol for abolition. It also resulted in an image of a black slave becoming incredibly famous at a time when black people were seen and treated as inferior. Despite the issues that the image of the kneeling slave begging for freedom poses, that of ignoring the awful mental and physical pain and torture slaves suffered as well as not recognising the important resistance that enslaved people instigated, the medallion was a symbol of revolution and remains in use today when remembering the atrocities of slavery and the work of abolitionists as well as in the fight against modern slavery and human trafficking.

[1] Wesley, John, Thoughts Upon Slavery, (R. Haws: University of California, 1774), p. 17.

[2] New Room museum

[3] New Room museum and David Dabydeen, ‘The Black Figure in 18th-Century Art’, BBC website, [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/africans_in_art_gallery_02.shtml].

[4] Thomas Clarkson, 1808 memoirs, from David Dabydeen, ‘The Black Figure in 18th-Century Art’, BBC website, [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/abolition/africans_in_art_gallery_02.shtml].

[5] Mary Guyatt, ‘The Wedgwood Slave Medallion: Values in Eighteenth-Century Design’ in Journal of Design History, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 93-105, p. 96.

[6] Thomas Clarkson, The History of the Abolition of the Slave Trade, (Jazzybee Verlag: Altenmunster), p. 144.

[7] Smith, Mark K., ‘Hannah More: Sunday schools, education and youth work’, in The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education, (2002). [http://infed.org/mobi/hannah-more-sunday-schools-education-and-youth-work/]

[8]https://www.history.ac.uk/1807commemorated/discussion/supplicant_slave.html

[9]https://www.history.ac.uk/1807commemorated/discussion/supplicant_slave.html

[10] Guyatt, p. 101.

[11] Guyatt, p. 99.