The last time I posted on this topic, I’ve discovered, was back in April last year. It’s been more than a year now, and I do feel that I have neglected poor old William Harris, having left him in Rome at the Carnival of 1822. That’s not to say that my  enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.

enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.

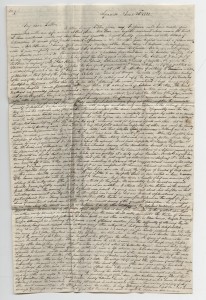

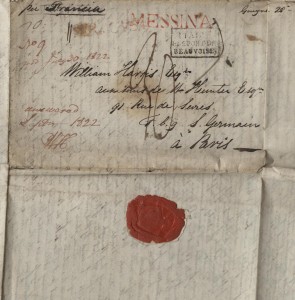

For anyone who is new to this series, some time ago (longer than I care to admit) one of our volunteers discovered some correspondence in an uncatalogued tin box which turned out to be letters written by one William Harris Junr. to his father, in Norton Place, during the 1820s. William (the younger) was an architect who had set off around Europe to discover the classical knowledge which was key to his profession, and undertook something of what we’d now call the role of art historian and archaeologist during his trip.Having crossed from Dover to Calais, taken in Paris, Geneva and the towns of northern Italy, William and his friends reached Rome in the autumn of 1821. From there, because of the ongoing wars in Greece, they set out for Sicily, where the journey eventually reached its thrilling conclusion.

If you’re new to this series, do take a look back at the other posts; if you’ve been following the story so far, I do hope that the long delay in this installment hasn’t put you off!

While the tourist brochure I was looking at provides much the same route as William took, the early nineteenth century experience of such tourism was rather different to our own. For one thing, the roads were more dangerous; our little group of travellers has already experienced the threat of robbery and kidnap, storms in the mountains and the threat of pestilence at Livorno. In addition, whether it’s particularly true of this group, or whether this applies more widely to travllers at this time, there seems to have been a fasination with getting close to danger. I’ve already related how William descended into a crater, tied to a piece of rope, but found that the heat of the (volcanic) earth scorched through his thick bootsoles in a few minutes. I imagine that, given the dangers inherent in travel, there had to be an element of the daredevil in you to set out on these journeys at all. This letter proves no exception: in June 1822, William and his friends decided to climb Mount Etna.

The missive is one of the longest in the series – not overwritten but put down in tiny handwritng on a large, unfolder sheet. Perhaps this was some of his drawing paper, requisitioned for the purpose, but in any case, for the sake of sanity, I’m going to have to split this letter into two. So, before they got as far as Etna, he and his friends took in the sights of Taormina, learned about local history and ran afoul of a Superior-General’s election.

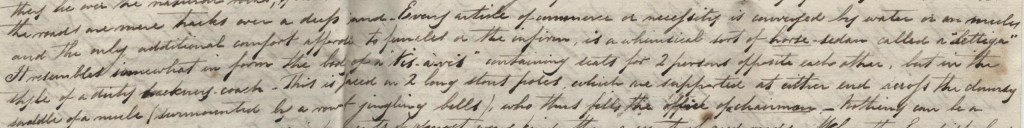

Of course, being drawn to danger did not necesarilly mean embracing discomfort: William found the lack of roads in Sicily deplorable, claiming that this was a detriment to ‘commerce and improvments of almost every kind’. Apparently, the English had earlier tried to build roads on the island, but their imposition of tolls on the populartion failed, since ‘the toll houses were destroyed in the night’. Since the roads couldn’t support a carriage of any kind, William noted the use of a ‘settiga’ in the locality, which he described as ‘a whimsical sort of horse-sedan…. It resembles somewhat the form of a “Vis-à-vis”…but in the style of a …hackney coach.’ This rather confusing description leads to all kinds of stretching of the imagination, but does show how alien William and his friends found the customs of this country which we now consider only a couple of hours’ distant.

Despite the intrigue of the settiga, donkeys were the made method of conveyance for the small band of architects as they set out from Messina on foot. At Palermo, the small group was joined by a Mr. Atkinson, ‘a well informed and agreeable man, about 30’. This gentleman had studied law, but had given up the profession and spent the previous four years travelling the Continent. As you may recall, the rest of William’s travelling companions were all architects (which has led me to wonder whether Europe was awash with young English architects at this point, or whether they just travelled in packs), but Atkinson need not have felt left out. William explains that Atkinson had spent the time travelling with two architects, friends of Thomas Angell, who had joined the group in Paris. The longest serving member of the group, besides William, seems to have been something of the comedy partner. Mr. Brooks arrived late in Dover, so that William considered leaving without him, insisted having packing cases of fashionable clothes sent out from England and appears to have let William add notes to his own letters to assure his family that he was safe. This trek from Messina to Taormina proved no different:

Brooks – who likes to get through the world easily – mounted a donkey at the end of the first 12 miles

The rest of the group, however, continued on foot, reaching Taormina only to discover that their timing had been somewhat unfortunate. While they had hoped to stay at the Benedictine Convent, they found that ‘the place was so full of priests’; 300, in face, who had assembled for the election of a Superior-general. Having reached their goal, the travellers were determined to make the best of it, and lodged at ‘a dirty inferior ‘Locanda’…into a room so filthy that after the first night we determined on sleeping at a tolerable inn 2 miles off and close to the sea shore’. This extra distance appears to have paid off, at least in terms of comfort, but did mean that the architects had to start the ascent to Taormina’s Greek ampitheatre before sunrise, to avoid the ‘fatigue of 2 miles of steep ascent’.

Once a part of the kingdom of Syracuse, the settlement of Taormina was well established by the time the Romans arrived in the third century BC. The town provided plenty ‘antiquities’, and was already popular with antiquarians when William and his friends visited. The theatre proved a point of particular interest for William;

The situation of this theatre is magnificent; placed on the ridge of a fine chain of mountains which run out to the sea, it commands scenery of the grandest description… Angell and myself…determined on measuring it – it proved a work of tedious duration from the difficulty of attaining dimensions, being much ruined

Of the other antiquities in the town, William proved less enamoured, adding that they were ‘generally much dilapidated.’ Perhaps the same could be said of the official to whom they were introduced in Taormina; ‘we immediately found he was an original character’, since he quickly showed them a bundle of materials he was looking to publish when he learned about the reason for their visit. They had further evidence of his status as ‘an original character’ that evening:

he gave us an invitation to attend his public lecture in the ancient Greek theatre in the evening. Several of his friends were present and a young man read aloud his chapter on that monument of antiquity which he interrupted “ever and anon” by his own personal explanations, given with great emphasis and in a strong nasal tone.

On 30 May, the group left Taormina for Nicolasai, where they found the widespread use of lava in buildings and the burnt soil made the place ‘sombre and uninviting’. The better sort of buildings met with more approval from the architects:

the cornices are of black lava and the walls covered with white plaster, a most singular contrast; one may almost call it architecture in mourning.

From there, they learned that a local physician and professor was in the habit of putting up travellers intent on climbing the mountain and, in spite of a rather English mix up over a lack of letters of introduction, William and his friends were welcomed to rest before their ascent the following day. Here, his letter breaks off to explain to his father that he will transcibe directly from his notebook – if this is the case, then he has a wonderful turn of phrase even when busy climbing a mountain!

William’s narrative is so illuminating and detailed that I think it’s best to leave this until another post – or else you’ll be here for another hour at least. But I promise I’ll do better, this time, to finish the tale in good time so that we can take in the last few stops on William’s journey at a leisurely pace. One thing you can be sure of – it won’t be a dull holiday, and there are probably more ‘original characters’ to come!