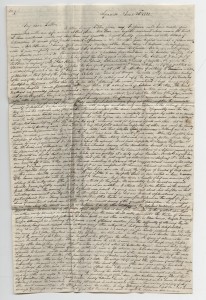

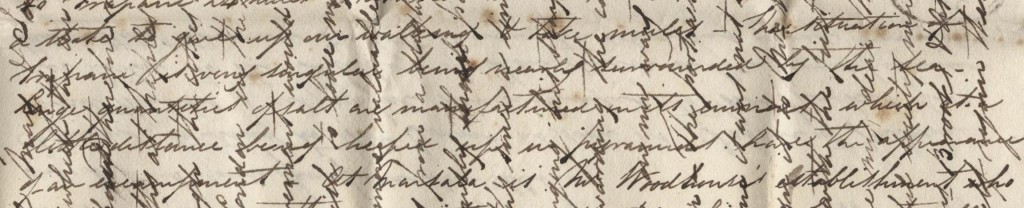

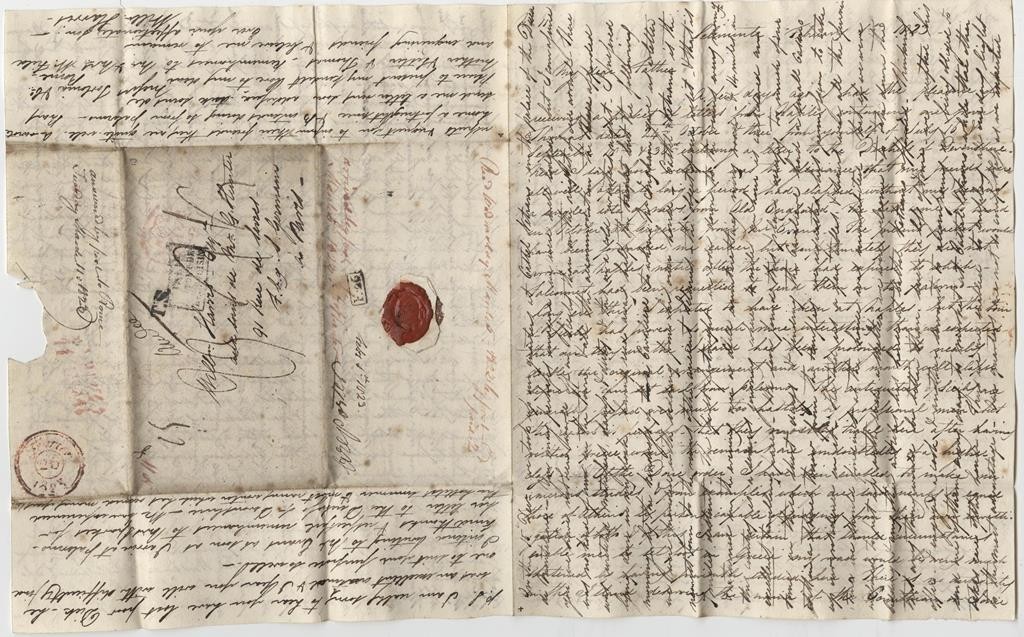

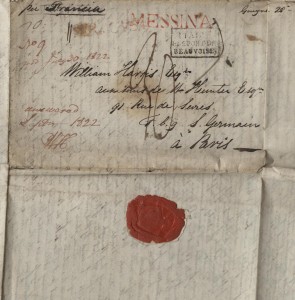

By the spring of 1823, William Harris Junior had experienced adventure, excitement and astonishment as he journeyed through Europe on a late version of the Grand Tour, extending his architectural studies. He and his small band of architects, gathered en route, had hoped to travel to Greece to take in the antiquities there, but the continent was hardly a tranquil place in the aftermath of Napoeonic War and Greece was out of bounds. Because of this, Harris and his remaining friends journeyed next to Sicily, and on the 1st February 1823, William wrote to his father from Selinunte. This detour, however, was no disadvantage, as he explained to his father;

“The antiquities of Sicily are generally passed over much too hastily by professional men but the reason is perhaps that they mostly travel here after having visited Greece where the remains are undoubtedly of a higher class.”

Indeed, William considered it best to have visited Sicily first, believing that the studies he made there would shorten the time it was necessary for him to spend in Greece.

The pleasant surroundings of Norton Street (far right) were a contrast to William’s accomodation on his travels.

In spite of the excitement of the journey thus far, and the strange and intriguing practices which William had experienced since leaving London in 1821, he still found life on the road a challenge. His father lived in the fashionable area of Norton Place (modern day Bolsover Street) in London, while William was appalled to hear that his sister and her family were having to move out of the capital. During his journey, however, William had to make do with what accommodation he could find; one night on the road, the small group were forced to “sleep on mattresses only in an uninhabited palace”. On 16th December, William and his friends stayed in the Ducal palace of Castel Vetrano, “but I can assure you we have not been worse off in Sicily than on the night of our arrival”.

“There was no kind of inn in the town and all the accommodation the palace afforded was wretched mattresses, damp and dirty, and this on a cold winter’s night. I preferred lying down in my cloak”

The gentlemen had better luck the following evening, however, when a local man known to Mr Ingham, an English merchant they had met on the road, provide bedding to lessen the austerity of the ducal quarters.

Elsewhere, they enjoyed better hospitality; amused “by the contrast between Sicilian and English manners”, William related their attendance at a ‘conversasione’ at Castel Ternisi, with a friend of Ingham’s:

“Ladies are rarely present at these parties, the Sicilians being of a very jealous turn and in this instance their places were supplied by a row of colored French portraits of the Beauties of different nations arranged around the walls. Several of the party wore white nightcaps among others an old Sicilian Baron but this practice is very general in Sicily.”

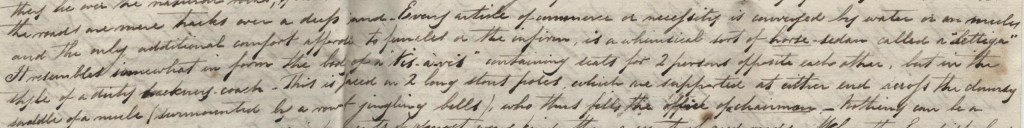

William had a habit of discovering friends on his travels. By the time of this letter, he was still in company with Mr Brooks, with whom he had travelled since France (the gentleman had turned up late at Calais), Thomas Angell and Mr Atkinson. In addition to Ingham, the group travelled from Gingenti with a Sicilian lawyer, who “afforded us some amusement on the road”. A “very timid horseman”, this lawyer got into difficulties when fording a river:

“he allowed his beast to lie down…skipping from his back [to a stone in the river]…. The animal no sooner found himself at liberty than he began to roll and completely bathed the saddle bags while the poor man hardly thinking himself safe on his little island desperately waded to shore.”

Harris and his friends, now seasoned travellers, were evidently highly amused by this escapade.

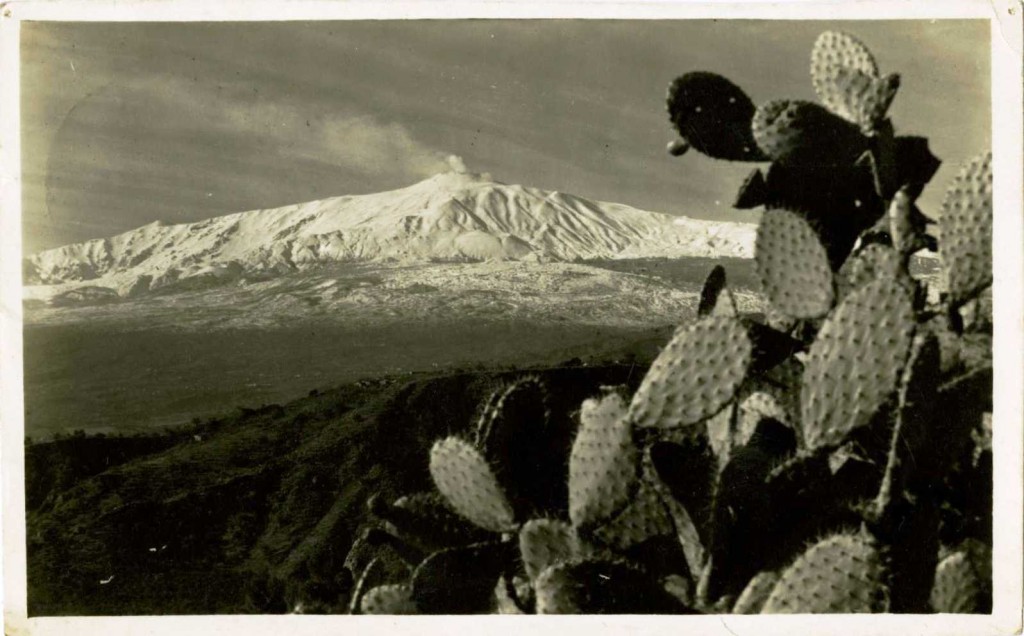

Even this far into the journey, after exploring the Mer de Glace of Mont Blanc and scaling Mount Etna, William still found new sights awe inspiring:

“About an hour before arriving at Palermo the heights command a fine view of the rich plains in which the city is built. A Theatre of mountains encircles it which running out into the sea form the two points of the Bay. The promenade at Palermo extends nearly a mile along the seaside. It surpasses even that of Naples and is by far the finest I have ever seen.”

Although the stay in Palermo proved short, William evidently liked the town, which abounded with convents and monasteries, many of which he described as occupying the upper stories on buildings, with shops on the lower floor. With palaces, Public Gardens and a fine promenade for both walking and driving, Palermo would have been a comfortable holiday destination, but William and his friends were seeking more adventure. Once they had their supplies, they set off for Segista: William and Atkinson on foot.

It was by damp, newly ploughed ground, that they found their way to Trapani, a town he described as ‘very singular being nearly surrounded by the sea’. It had, William added, ‘the appearance of an encampment’, due to its pyramids of salt heaped around its environment. The salt trade served William and his friends well, as one of its key merchants, a Mr Woodhouse, “received us in the most hearty manner”.

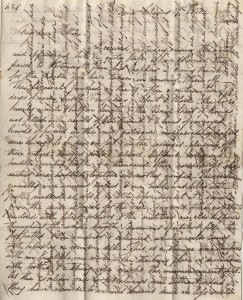

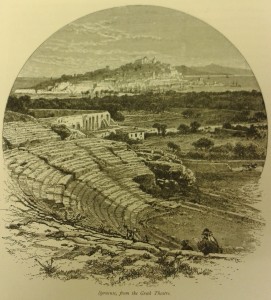

However, it was the ruins of ancient Selinus which had been the object of all this travel, a site which William explained comprised six temples: three on one hill and three on another. The original plan had been to lodge in Castel Vetrano and journey to study the site each day, but the architects’ enthusiasm soon made them begrudge the amount of time they had to spend travelling to and from their studies. With the permission of the Cavaliere, they thus moved into a small house ‘within a stone’s throw from the temple’. It was largely unfurnished, but the Cavaliere permitted the architects to take furniture from Vetrano, and the gentlemen soon took on a cook and a servant, one to take care of the house and the other to visit the market at Castel Vetrano each day. This, William explained, enabled the gentlemen to ‘employ all our day light to the most advantage’.

However, it was the ruins of ancient Selinus which had been the object of all this travel, a site which William explained comprised six temples: three on one hill and three on another. The original plan had been to lodge in Castel Vetrano and journey to study the site each day, but the architects’ enthusiasm soon made them begrudge the amount of time they had to spend travelling to and from their studies. With the permission of the Cavaliere, they thus moved into a small house ‘within a stone’s throw from the temple’. It was largely unfurnished, but the Cavaliere permitted the architects to take furniture from Vetrano, and the gentlemen soon took on a cook and a servant, one to take care of the house and the other to visit the market at Castel Vetrano each day. This, William explained, enabled the gentlemen to ‘employ all our day light to the most advantage’.

These quarters were ‘not so comfortless as we expected’, perhaps in part due to their experiences thus far on their travels. In any case, William explained to his father in London, although the windows had only shuttered, having never been glazed, the Sicilian weather made this quite bearable. “By this you may see how totally different is the climate of Sicily from that of our foggy atmosphere.” And in any case, the location enabled the William, his friend Angell and the rest, to make some exciting discoveries.

According to William, there was some material published on three of the temples by an architect named Wilkins ‘who formally lived in New Cavendish Street’, but this was ‘full of errors’. The rest, nearest to the sea shore (one no more than ¼ mile from it) had, Harris stated, ‘never been published at all certainly not in England’. This, then, was an exciting opportunity for the young architects.

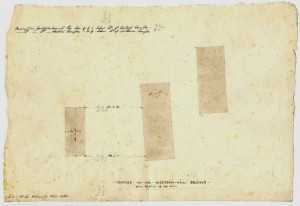

Ground plan of three temples (O, C and D) on the Western Hill at Selinunte, drawn by William Harris. From the British Museum Collections.

“They are all a heap of ruins but all the points may be form[e]d or nearly so with a little trouble. By the help of a little excavation we have able to form (I hope) tolerably correct ideas of their plans and proportions. The advantage of being on the spot has perhaps never been possessed by any travellers before.”

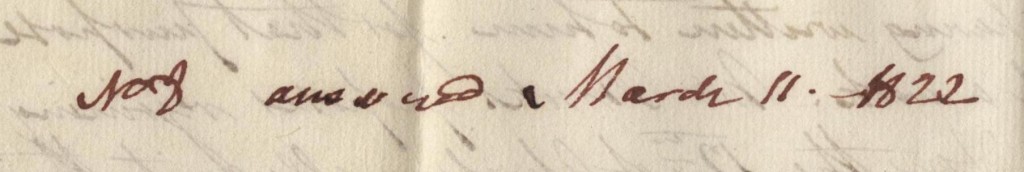

In closing the letter, William detailed the architects’ plans for the following months, begging his father for an extension to his trip – adding that Angell had already received just such a dispensation from his father. He explained: “a year’s study at the end of a tour is certainly more valuable than two at its commencement”. There was still much, after all, to see: Naples, Pompeii, Herculaneum and, he still hoped, Greece. Harris intended to begin his homeward journey in the spring of 1824, via the Venetian States, to arrive in London at the end of June. By then, he would have been away from home for 3 years, and have experienced much on his journey. But these plans were never to come to fruition. In the excavations at Selinus, Harris and Angell discovered far more than they ever bargained for, and their youthful enthusiasm would result in a rather sudden journey home for just one of the pair: the other would never return to London.

In a postscript, William adds the note “I am really sorry to hear you have lost poor Dick” – this was the horse whose illness had provoked much comment in previous correspondence between father and son. Having been lamed but undergone an operation, it seemed that Dick had never recovered. William noted: “he was an excellent animal and I fear you will with difficulty find one to suit your purpose so well”.

Recently, there’s been an exciting development in this tale: drawings by Harris and Angell, deposited at the British Museum are now being catalogued and digitised. I hope you’re as excited as me about this: you can see more on the BM’s Collection Online pages.

enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.

enthusiasm for discovering more about his journey has diminished; in fact, the other day I was idly glancing through a holiday brochure and saw a package tour around Sicily, covering Mount Etna, Palermo, Siracusa and Taormina and got a bit over excited. No, this isn’t my planned holiday for this year (not at that price!) but this does follow the journey which William and his friends took nearly 200 years ago. In fact, it looks like William was part of the team which undertook some of the earliest work on these now very popular tourist destinations.